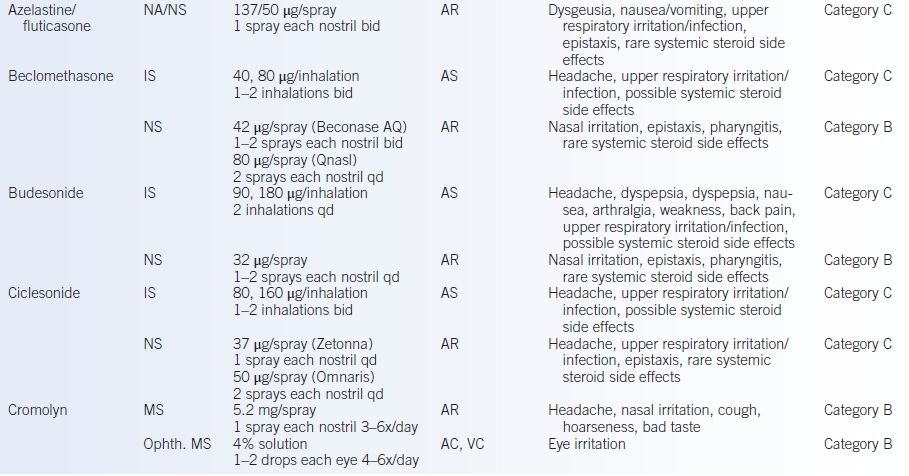

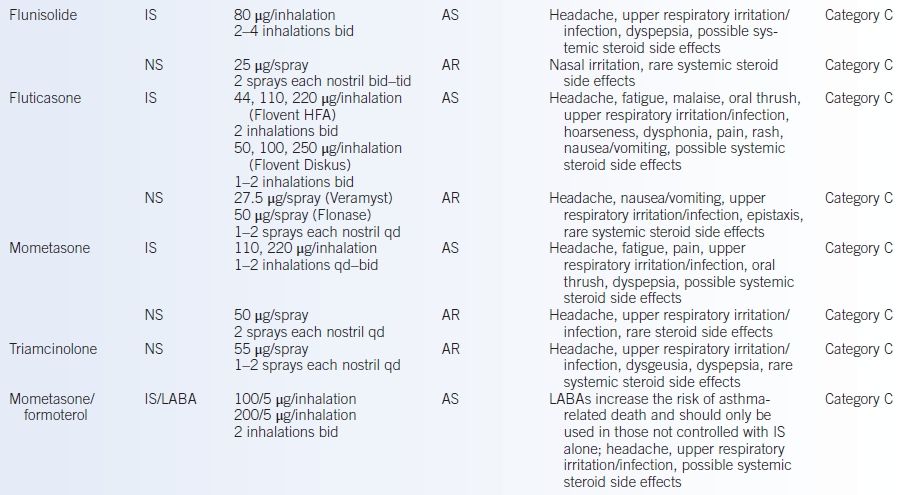

A-1st, first-generation antihistamine; A-2nd, second-generation antihistamine; AC, allergic conjunctivitis; ANA, anaphylaxis; AR, allergic rhinitis; AS, asthma; IAC, inhaled anticholinergic; IS, inhaled steroid; LABA, long-acting bronchodilator; LTA, leukotriene antagonist; MS, mast cell stabilizer; NA, intranasal antihistamine; NAC, intranasal anticholinergic; NAR, nonallergic rhinitis; NS, nasal steroid; OA, ocular antihistamine; SABA, short-acting bronchodilator; UR, urticaria; VC, vernal conjunctivitis.

aIncludes pregnancy category: A, human studies show no risk; B, no evidence of risk in studies; C cannot rule out risk due to lack of studies; D, evidence of risk.

bTime before skin testing that antihistamine should be discontinued.

Corticosteroids

- Steroids inhibit the production of cytokines, which effectively prevents the late-phase response. Steroids do not block the immediate-phase response and are not a contraindication to skin testing.

- Long-term use of steroids is associated with side effects. The risk of side effects is much greater with systemic (oral) steroids than with topical (inhaled) steroids.

- Posterior capsular cataracts are associated with prolonged use, and annual ophthalmologic examinations are recommended for patients on any continual steroid dose (inhaled or oral).

- Adrenal suppression occurs with extended use of oral (any dose) or high-dose inhaled steroids. Short courses (less than a month) of oral steroids do not appear to have a significant effect on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis.

- Osteoporosis is a risk of corticosteroid use; patients should be encouraged to take supplemental calcium and may require bone density scans to evaluate their risk.

- Posterior capsular cataracts are associated with prolonged use, and annual ophthalmologic examinations are recommended for patients on any continual steroid dose (inhaled or oral).

Immunotherapy

- Indications include allergic rhinitis, venom hypersensitivity, and atopic dermatitis if associated with aeroallergen sensitivity. The mechanisms of action are still under investigation.

- Treatment consists of initial SC injections that contain increasing doses of the allergen extracts to which the patient is sensitive. Once the buildup phase is completed, the patient is kept at a maintenance dose for several years. The recommended length of therapy is variable (usually at least 3 to 5 years). Immunotherapy should be prescribed by an allergist only after skin testing or, under special circumstances, based on the results of in vitro testing.

- Adverse reactions are usually mild, with only localized pruritus, erythema, and edema. However, some reactions can be severe and include asthmatic flares, diffuse urticaria, and even anaphylactic shock.

- The highest risk of a reaction is during the initial buildup phase; however, a reaction may occur at any dose.

- A physician and staff who are experienced in treating anaphylactic shock and an emergency cart must be immediately available.

- The risk for a reaction from an injection is greatest up to 30 minutes following the shot (60 minutes for venom immunotherapy), and patients should not be allowed to leave the office until this period has passed.

- Any time that a patient has had a significant reaction, immunotherapy should be held, pending discussion with an allergist.

- The highest risk of a reaction is during the initial buildup phase; however, a reaction may occur at any dose.

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

Environmental control measures are the first and most important therapy for allergic disorders. These interventions limit or prevent exposure to allergens. Examples of appropriate control measures include the following:

- Pets (in particular pets with fur)

- Keep pet out of home or at least out of the bedroom.

- Remove carpeting.

- Wash the pet regularly.

- Keep pet out of home or at least out of the bedroom.

- Dust mites

- Wash bedding in hot water (≥130°F) weekly.

- Use synthetic pillows, blankets, and mattresses.

- Encase the pillows and mattress in dust mite–proof encasings.

- Maintain home humidity level at <45%.

- Wash bedding in hot water (≥130°F) weekly.

ANAPHYLAXIS

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Anaphylaxis represents the rapid release of mast cell mediators. The symptoms of anaphylaxis may be related to one or, more commonly, multiple organ systems and are among the most rapid and profound of the allergic reactions; without rapid treatment, they may prove to be fatal.

- Anaphylactic reactions are not rare. Lifetime prevalence is 0.05% to 2%.

- Antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most common culprits in adults. Insect stings are another common cause.

- Penicillin reactions occur in 1 to 5 per 10,000 patient courses of treatment, and fatalities can occur at 1 per 50,000 to 100,000 courses.

- Antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most common culprits in adults. Insect stings are another common cause.

- Although the office management is essentially identical, anaphylaxis can be divided into two broad categories: IgE mediated and non–IgE-mediated (formerly known as anaphylactoid reactions).

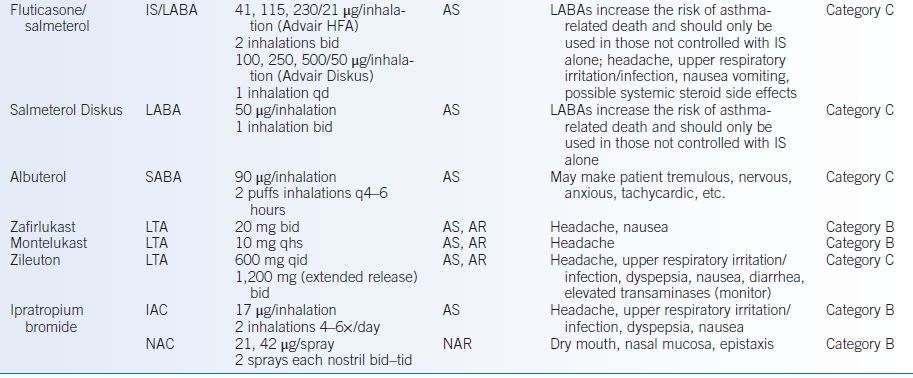

Classification

- Anaphylactic reactions can be classified according to the severity of the reaction. The most common classification is shown in Table 39-2.

- Anaphylaxis may be monophasic, biphasic, or, in rare cases, prolonged. As noted previously, classic allergic reactions may have an early and a delayed or late phase. It is not uncommon to see a patient successfully treated for anaphylaxis has a second, often equally profound, reaction 4 to 12 hours following the initial anaphylactic reaction.

TABLE 39-2 Classification of Anaphylactic/Anaphylactoid Reactions According to Severity

Pathophysiology

- The rapid release of vasoactive mediators results in a loss of vascular tone, resultant pooling in the splanchnic bed, and functional hypovolemia. Because of increased capillary permeability, fluid and colloid are lost into the extravascular space and the net effect is a profound decrease in blood pressure (BP).

- Other manifestations of anaphylaxis include bronchospasm, laryngeal edema, profuse nasal discharge, watery itchy eyes, marked postnasal drip, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, uterine cramping, urticaria, angioedema, and rarely anaphylactic-induced pulmonary edema and acute heart failure.

Prevention

- Prevention is one of the most important aspects of management.

- Emphasis should include instructing the patient that most severe reactions (including those to food, drugs, stinging insects, and radiocontrast media) rarely go away. If these reactions are identified, the patient should be advised to avoid that agent in the future. Individuals who are food sensitive should read all labels for prepared food and inquire for the presence of that food at restaurants. The Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network (http://www.foodallergy.org, last accessed 1/13/15) can help individuals by identifying food that contains potent allergens and in designing meals that avoid those allergens.

- Every patient who has experienced anaphylaxis in the past should have a self-injectable epinephrine prescribed and should carry it at all times. A medical alert bracelet or necklace that identifies important allergens (especially drug allergy) is also an important preventive measure.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is likely when one of the three following criteria occurs:

- Acute skin and/or mucosal symptoms (e.g., hives, pruritus, flushing, and lip/tongue/uvula swelling) and one of the following:

- Respiratory symptoms (e.g., wheezing, stridor, shortness of breath, hypoxia)

- Hypotension or associated end-organ dysfunction (e.g., hypotonia, syncope, or incontinence)

- Respiratory symptoms (e.g., wheezing, stridor, shortness of breath, hypoxia)

- Exposure to probable allergen and greater than or equal to 2 of the following:

- Skin-mucosal tissue involvement

- Respiratory symptoms

- Hypotension or end organ dysfunction

- Persistent gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., emesis, abdominal pain)

- Skin-mucosal tissue involvement

- Decreased BP after exposure to a known allergen: systolic BP <90 mm Hg or >30% decrease.4

TREATMENT

- Perhaps, the most important aspect of the treatment of anaphylaxis is the early recognition and treatment. If anaphylaxis is suspected, treatment should be initiated without waiting to see if the reaction becomes worse. True anaphylaxis rarely goes away without treatment.

- The cornerstone of treatment is placing the patient in supine position with rapid administration of epinephrine and fluid. Other therapies may be added later. Most studies of fatal anaphylaxis have demonstrated failure to introduce these measures as a major contributor to the adverse outcome.

- Patients with acute anaphylaxis are often hypoxic. Thus, the rapid establishment of an adequate airway is critical.

- The outpatient treatment of anaphylaxis should be directed toward stabilizing the patient to assure a patent airway and maintain an adequate BP. Once this has been established, the patent should be rapidly transported to an emergency care facility.

Basic Office Emergency Kit

This should include the following:

- Epinephrine: 1:1,000 aqueous for SC and IM use and 1:10,000 aqueous for IV use

- Racemic epinephrine: inhaler or nebulizer use

- IV fluids: colloid and crystalloid

- Large-bore IV catheter

- Tourniquet

- Oxygen with face mask or nasal prongs

- Ambu bag

- Additional medications: H1 antihistamines, H2 antihistamines, and corticosteroids

Medications

Adrenergic/Sympathomimetic Agents

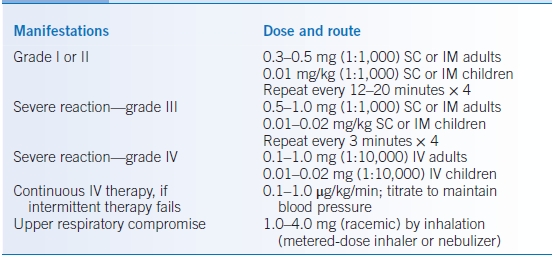

- The most important agent for the treatment of anaphylaxis is epinephrine, which should be given as soon as the reaction is recognized. The usual doses for epinephrine are shown in Table 39-3. It is important to remember that in most cases, SC or IM epinephrine is adequate, with recent data suggesting that IM administration is preferred.

- Intravenous epinephrine should always be given using 0.1 mg/mL or 1:10,000 aqueous. Intermittent epinephrine can be repeated at 15- to 20-minute intervals and, after four doses, if necessary, can be followed by continuous intravenous therapy until the BP is stabilized.

- Other sympathomimetic agents that may be useful include terbutaline (given SC or IM), dopamine, dobutamine, and norepinephrine. In general, these agents are used in profound and prolonged anaphylactic reactions and are beyond the scope of this chapter.

- Aerosolized racemic epinephrine can be tried in patients who have laryngeal edema; however, if this is not available or is not rapidly effective, use of an endotracheal tube, cricothyroid puncture, or tracheotomy may be necessary to protect the airway. The establishment of an airway should be accompanied by the use of oxygen therapy.

TABLE 39-3 Doses for Epinephrine in the Treatment of Anaphylaxis

Fluids

- Establishment of IV access and the institution of fluid replacement therapy should be accomplished as soon as epinephrine has been given.

- Two types of fluids are available for therapy, colloid (albumin, hydroxyethyl starch [hetastarch], pentastarch, dextrans, and blood and blood products) and crystalloid (dextrose, saline, and Ringer lactate).

- The choice between colloid and crystalloid has received significant attention. Colloid solutions have been associated with increased oxygen saturation and less increase in lung water than crystalloid solutions. Some colloid solutions are associated with adverse side effects, such as anaphylactoid reactions (dextrans) and potential for infectious diseases (blood and blood products). Of the colloid solutions, hydroxyethyl starch is the preferred solution. An initial infusion of 500 mL is followed by any crystalloid fluid with a goal of maintaining adequate BP.

Antihistamines

- Antihistamines are a useful adjunct (IV, IM, PO), particularly for patients who experience urticaria or generalized skin pruritus.

- However, antihistamines are not a substitute for epinephrine and fluids. One should not give an antihistaminic and then wait to see if it is effective, even in mild anaphylaxis.

Other Agents

- Glucagon: May be effective in patients taking β-blockers.

- β-Agonists: Patients who experience significant bronchospasm should receive a short-acting β-agonist.

VENOM HYPERSENSITIVITY

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Only insects with true stingers are included within the order hymenoptera. Some examples are yellow and bald-faced hornet, yellow jacket, paper wasp, honeybee, and fire ants.

- Venom protein includes many vasoactive amines, alkaloids, and species-specific proteins, such as hyaluronidase, acid phosphatase, and phospholipase A.

- Estimates suggest that 6% to 17% of the population in the US have specific IgE against hymenoptera venoms with a small predilection toward males.5

- Clinically significant hymenoptera venom allergic reactions occur in approximately 3% of adults and 0.6% to 0.8% of children.3

- Local reactions are characterized by induration, erythema, and pain at the sting site. The area involved can spread to regions of the body that are directly adjacent to the sting site, but as long as these sites are contiguous, the reaction is still considered local. These reactions are often quite dramatic and may last for up to a week, but they rarely progress and need no further evaluation.

- Systemic reactions include any reactions that occur away from the initial sting site.

- Systemic reactions can include urticaria, bronchospasm, laryngeal edema, hypotension, and other symptoms of anaphylaxis.

- Most patients who have a severe reaction have no history of venom-induced anaphylaxis.

- In patients with a history of a systemic reaction, 60% have a similar reaction with a re-sting; without intervention, this risk decreases to 40% at 10 to 20 years since the previous sting.

- Systemic reactions can include urticaria, bronchospasm, laryngeal edema, hypotension, and other symptoms of anaphylaxis.

- A prior sting sensitizes the individual to the hymenoptera venom, producing a specific IgE. Each subsequent sting can cause an increased likelihood of sensitization.

DIAGNOSIS

- Type of insect: It is important to identify the stinging insect, as this will guide skin testing and ultimate therapy. It is also helpful to determine if the patient was stung once or multiple times and by one or more insects.

- Site of sting: The location of the sting may be important in determining whether or not a systemic reaction occurred. It can also aid in identification of the insect involved. For example, honeybees usually sting only when they are stepped on. Yellow jackets, however, attack people when their food source is threatened. This usually happens in the late fall, when they can be found scavenging for food in garbage containers.

- Various concentrations of venoms are used to determine sensitivity to hymenoptera venoms. False-positive skin test results may be due to venom cross reactivity.

- It is preferable to wait 3 to 6 weeks after having a reaction before skin testing to prevent false negatives.

TREATMENT

- Local reactions require supportive care of ice, compression, and elevation. In severe local reactions, corticosteroids (usually 0.5 mg/kg prednisone) are sometimes prescribed to help decrease edema and irritation. Antihistamines can help alleviate the pruritus that is often associated with a sting.

- Systemic reactions

- Acute treatment of a systemic reaction includes the liberal use of IM (preferable) or SC epinephrine (Table 39-3) to rapidly treat anaphylaxis.

- β-Agonists are useful if bronchospasm develops from the sting (e.g., albuterol metered-dose inhaler or nebulizer).

- Antihistamines are also helpful in the acute treatment to block the effects of histamine release.

- Corticosteroids (0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg prednisone for 7 to 10 days) reduce edema as well as help prevent a late-phase response from occurring.

- Long-term therapy involves initiation of venom immunotherapy, which has been shown to reduce the patient’s risk of a systemic reaction from a subsequent sting to that of the general population. In addition to immunotherapy, any patient who has had a systemic reaction to a sting should have self-injectable epinephrine (EpiPen) prescribed and be taught how to use it appropriately. Besides epinephrine, these patients should have antihistamines with them at all times. Patients are also encouraged to wear a medical alert bracelet that identifies them as venom allergic.

- Immunotherapy

- Once patients begin venom immunotherapy, they are protected from subsequent stings, even if they are in the buildup phase of the injections.

- The maintenance dose of the injections usually contains 100 μg venom proteins—roughly 1.5 to 2.0 times the amount in a single sting.

- The question of how long a patient should continue to receive immunotherapy is still under investigation. Some physicians treat for 5 years and then discontinue the shots, whereas others continue immunotherapy until the patient’s skin test results become negative or at least a log-fold less reactive. The patient, primary care physician, and allergist should all be involved in the decision of when to discontinue immunotherapy.

- Once patients begin venom immunotherapy, they are protected from subsequent stings, even if they are in the buildup phase of the injections.

- Acute treatment of a systemic reaction includes the liberal use of IM (preferable) or SC epinephrine (Table 39-3) to rapidly treat anaphylaxis.

URTICARIA AND ANGIOEDEMA

Approximately 15% to 24% of the US population will experience at least one episode of urticaria (hives), angioedema, or both in their lifetime.6 Among those experiencing either angioedema or urticaria, approximately 50% will present with both conditions simultaneously, while about 10% experience chronic urticaria without angioedema.7

Urticaria

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Urticaria is an erythematous maculopapular eruption in the superficial layers of the dermis and is associated with pruritus.

- It can be further divided into acute and chronic lesions based on the temporal nature of the rash.

- Acute urticaria is any urticarial episode that lasts for <6 weeks.

- Chronic urticaria is when the episode lasts for >6 weeks. An urticarial episode consists of a period when hives are present daily or nearly daily. It should be noted that a given crop of hives will likely be present only for a short period, but the patient may have multiple crops of hives during the episode.

Etiology

- Acute urticaria: Most of the inciting agents that lead to acute urticaria can be easily identified because of the close temporal relationship between exposure and hive development. Often, the patient has already identified the responsible agent before seeking medical attention.

- Foods: Milk, egg, fish, tree nuts, wheat, soy, peanuts, and shellfish are most common.

- Medications: For example, penicillin.

- Infections: Usually viral infections.

- Physical causes:

- Cold, heat, pressure, sun, water, vibration, cholinergic stimulation, and exercise.

- In some patients, exercise is a trigger only when closely preceded by eating.

- Cold, heat, pressure, sun, water, vibration, cholinergic stimulation, and exercise.

- Foods: Milk, egg, fish, tree nuts, wheat, soy, peanuts, and shellfish are most common.

- Chronic urticaria:

- The inciting agents that lead to chronic urticaria are much more difficult to identify because the temporal relationship is not as clear.

- These patients tend to be more emotionally and physically affected by their disease and its chronicity.

- Chronic urticaria has been attributed to the following:

- Medications: for example, NSAIDs.

- Collagen vascular disease: for example, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Neoplasia.

- Autoimmune diseases: most often associated is thyroid disease. Patients may be hypo-, hyper-, or even clinically euthyroid but usually have antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies. In these patients (including the clinically euthyroid), treatment with physiologic doses of thyroid hormone often leads to resolution of the urticaria.

- Diet: frequently eaten foods.

- Medications: for example, NSAIDs.

- Patients with chronic urticaria who have autoantibodies directed against either IgE or the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) do not respond well to antihistamines alone and often require corticosteroids for relief of their hives. Further treatment options for these patients include cyclosporine.8

- The inciting agents that lead to chronic urticaria are much more difficult to identify because the temporal relationship is not as clear.

- Idiopathic urticaria, the largest set of urticarias, is a catch-all group that represents those cases in which no etiology for the urticaria can be discerned.

Pathophysiology

- Urticaria is dermal edema resulting from vascular dilatation and leakage of fluid into the skin in response to molecules (histamine, bradykinin, leukotriene C4, prostaglandin D2, and other vasoactive substances) released from mast cells and basophils.9

- The prototypical lesion and pruritus are the result of H1 histamine receptor activation on endothelial and smooth muscle cells leading to increased capillary permeability and H2 histamine receptor activation leading to arteriolar and venule vasodilation.

- Urticaria can be classified as immunologic or nonimmunologic.

- Immunologic urticaria:

- Includes processes mediated by antibodies and/or T cells that result in mast cell activation.

- Urticaria may result from the binding of IgG autoantibodies to IgE and/or to the receptor for IgE molecules on mast cells, representing a type II hypersensitive reaction. These autoimmune urticarias represent 30% to 50% of patients with chronic urticaria. However, mast cell activation can also result from type I, type III, and type IV hypersensitivity reactions.

- Includes processes mediated by antibodies and/or T cells that result in mast cell activation.

- Nonimmunologic urticarias: Result from mast cell activation through membrane receptors involved in innate immunity (e.g., complement, Toll-like, cytokine/chemokine, and opioid) or by direct toxicity of xenobiotics (haptens, drugs).

- Urticaria may result from different pathophysiologic mechanisms that explain the great heterogeneity of clinical symptoms and the variable responses to treatment.10

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Determine whether the urticaria is acute or chronic.

- It is also important to determine whether the lesions are pruritic or painful. Because vasculitis may present with urticarial lesions, it is critical to determine whether the individual crops of hives last for >24 hours and whether they resolve with scarring. Both of these conditions are associated with urticarial vasculitis, not urticaria.

- Specifically, the physician should look for evidence of thyroid disease, collagen vascular disease, occult infection, or malignancy.

- Several types of urticaria can develop from physical causes. These physical urticarias can be diagnosed by using various maneuvers to reproduce them. For example, cold urticaria can be diagnosed by placing an ice cube on the forearm for 4 minutes. The cube is then removed and the arm observed for 10 minutes. A hive that develops at the same location where the ice cube was indicates a positive test result.

Diagnostic Testing

- Consider checking complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function tests, antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, and urinalysis.

- Chronic urticaria index: Commercially available test to detect presence of anti-FcεRI autoantibodies may be obtained. Autologous serum skin testing is another option.

- Skin and in vitro testing:

- Although the specific antigens that are responsible for urticaria are often hard to discern, it may be helpful in some patients to perform skin or in vitro testing.

- These tests tend to be more useful in patients with acute urticaria in whom a specific food or medication is believed to be the offending agent.

- Skin testing is the preferred modality to evaluate for allergy; however, patients with severe urticaria may require in vitro testing.

- Although the specific antigens that are responsible for urticaria are often hard to discern, it may be helpful in some patients to perform skin or in vitro testing.

- In addition to specific food allergens, urticaria can develop from sensitivity to food additives. The only reliable test for sensitivity to food additives is a double-blind placebo-controlled challenge. These are usually performed in an allergist’s office and take several hours to complete.

TREATMENT

- The most important therapeutic intervention is to avoid the inciting agent(s) and/or treat the underlying condition.

- Medications include use of antihistamines often in escalating doses, to control the pruritus and urticarial flares (see Table 39-1 for medications and doses). Patients may benefit from the addition of an H2 receptor antagonist (cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, etc.).

- Tricyclic antidepressants, such as doxepin (starting dose, approximately 10 to 25 mg daily), are often used because of their strong antihistaminic activity. Because these medications are often sedating, they should be given shortly before or at bedtime.

- Corticosteroids can be used (prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg daily) to alleviate urticarial flares, but the numerous side effects of chronic use limit their use in chronic urticaria.

- In patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria, it is helpful to control their urticaria with appropriate doses of medications and then withdraw the medications after a specified duration of time (6 weeks to 6 months) to evaluate for the continued presence of urticarial lesions. If the hives recur, restart the medications for another period of time.

Angioedema

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Angioedema consists of edema in the deep layers of the dermis and is usually characterized by pain rather than pruritus, as seen with urticaria. Angioedema without urticaria usually presents as a painful, nonpruritic swelling of the deep dermis.

- Allergic angioedema is due to an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to drugs, foods, environmental exposures, insect stings, or other substances resulting in histamine release from mast cells.11 Most cases, however, are idiopathic.

- Nonallergic angioedema occurs mostly as a result of increased bradykinin levels.12,13 It can be further classified into hereditary, drug induced, acquired, and miscellaneous.

- Acquired angioedema:

- Acute: Allergic, IgE-mediated drugs (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, NSAIDs, fibrinolytic agents, estrogen, narcotics, some antibiotics), foods, insect bites, pollens and fungi, contrast dyes/drugs, serum sickness, and necrotizing vasculitis

- Chronic: Idiopathic, acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency, angioedema-eosinophilia syndrome, and vibratory angioedema

- Acute: Allergic, IgE-mediated drugs (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, NSAIDs, fibrinolytic agents, estrogen, narcotics, some antibiotics), foods, insect bites, pollens and fungi, contrast dyes/drugs, serum sickness, and necrotizing vasculitis

- Hereditary angioedema (HAE): The kallikrein-kinin system fails to be inhibited because of C1 inhibitor (C1INH) absence/dysfunction and leads to early-acting complement components C4 and C2 to be low.14

- Type 1: C1INH deficient or absent due to mutation (80% to 85% of HAE patients)

- Type 2: C1INH dysfunctional (15% to 20% of HAE patients)

- Type 3: C1INH level normal. Occurs in X-linked dominant fashion and therefore affects mainly women15

- Type 1: C1INH deficient or absent due to mutation (80% to 85% of HAE patients)

- A deficiency in C1INH can also be acquired, often associated with a hematologic malignancy and the subsequent production of an autoantibody that blocks the function of otherwise normal C1INH.

- In most cases, angioedema is due to either a drug (such as an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB], aspirin, an antibiotic, or an NSAID) or C1INH.

- Angioedema from an ACE inhibitor or ARB can occur at any point during a course of treatment and necessitates discontinuation of the drug, even if it is not the cause, because these drugs can enhance angioedema caused by other factors.

- Clearly, all drugs of the same class need to be avoided; however, it is less clear whether sensitivity to one class necessitates avoidance of the other. However, several case histories have been reported in which angioedema has developed in patients with ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema when treating with an ARB therapy.16

- Therefore, if possible, it is probably best to avoid both classes of medications if a patient develops sensitivity to one of them.

- Clearly, all drugs of the same class need to be avoided; however, it is less clear whether sensitivity to one class necessitates avoidance of the other. However, several case histories have been reported in which angioedema has developed in patients with ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema when treating with an ARB therapy.16

DIAGNOSIS

- The most commonly affected areas are the soles of the feet, palms of the hands (including the thenar eminence), buttocks, and face (including the larynx, lips, tongue, and periorbital regions).

- Attacks can occur after even minimal trauma and may progress around the body. The greatest danger with angioedema is that it may involve the larynx and can lead to complete obstruction of the airway.

- Evaluation of HAE:

- To evaluate for possible deficiency in C1INH, a C4 level can be obtained. This is low even between attacks in HAE.

- Further evaluation includes a quantitative C1INH level. If this is not significantly decreased, a functional C1INH level should be obtained. This is reduced in either acquired or hereditary forms.

- Finally, low C1q level combined with a low C1INH and C4 warrants a workup for acquired angioedema.

- Patients with known or suspected angioedema due to a complement deficiency should be evaluated by an allergist/immunologist.

- To evaluate for possible deficiency in C1INH, a C4 level can be obtained. This is low even between attacks in HAE.

TREATMENT

- Avoidance of the causative agent is the primary treatment in drug-induced angioedema. As mentioned above, a reaction to an ACE inhibitor or ARB may be the reason to avoid all drugs of both classes.

- In cases in which angioedema is secondary to a malignancy, treatment of the underlying disease leads to resolution of the angioedema.

- For the treatment of acute angioedema, antihistamines and corticosteroids are helpful. Epinephrine can be lifesaving for severe reactions.

- Treatment of HAE should be managed by an allergist/immunologist. The following is an overview of the current treatment options:

- Berinert (C1 esterase inhibitor [human]): Plasma-derived concentrate of C1 esterase inhibitor.17

- Kalbitor (ecallantide): Reversible inhibitor of plasma kallikrein that has been shown to be effective for acute attacks of swelling in HAE.18

- Epinephrine has often been used for HAE, but there is no data to support its efficacy.

- The use of antihistamines and corticosteroids is of little value.

- Cinryze (C1 esterase inhibitor [human]): FDA-approved C1 esterase inhibitor that helps prevent swelling and/or painful attacks in teenagers and adults with HAE.19

- Androgens (usually stanozolol) increase the levels of C1INH and prevent attacks of angioedema.

- Supportive therapy is always important. Laryngeal angioedema may develop, and therefore, it is always important to safeguard the airway. Some patients may even require intubation or tracheostomy during their attacks.

- Berinert (C1 esterase inhibitor [human]): Plasma-derived concentrate of C1 esterase inhibitor.17

DRUG ALLERGIES

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Epidemiology

- Allergic reactions to drugs represent a major contributor to the spectrum of adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

- Studies suggest that as many as 15.1% of hospitalized patients in the US experience an ADR with an incidence of 3.1% to 6.2% of hospital admissions due to an ADR.20

Classification

- Reactions related to the pharmacologic properties of the drug such as side effects, toxic reactions, and drug interactions. These reactions are based on the chemical properties of the drug and therefore occur in all patients if a sufficient amount of drug is given. In many cases, the reaction may be lessened by decreasing the dose of the drug.

- Reactions due to toxic metabolites may mimic immunologic reactions or side effects. In this case, the biotransformation product rather than the drug itself is the offending agent. The reaction to sulfa-containing drugs (mostly sulfamethoxazole in patients who are HIV positive) is an example of this reaction. These reactions are different from other side effects, and the method for abrogating the reaction differs from that of other types of ADRs.

- Idiosyncratic reactions are adverse effects with an unknown mechanism. They are seen in susceptible individuals, but the basis for the susceptibility is not known. They can occur at any point during therapy. The reactions may be mild, such as the facial dyskinesis that is seen with phenothiazines, or devastating, such as the aplastic anemia with chloramphenicol. Idiosyncratic reactions almost invariably recur if the drug is reintroduced.

- Immunologic reactions:

- Reactions due to the production of antibodies or cytotoxic T cells directed against the drug or a biotransformation of the drug.

- Examples include contact sensitivity of fixed drug reactions (type IV or cell-mediated reaction); tissue-specific reactions due to T-cell immunity, such as drug-induced hepatitis; tissue-specific damage due to IgG antibodies (type II or III); and drug allergy due to IgE antibodies (type I).

- Other reactions are believed to have an immunologic basis, but the exact mechanism has not been elucidated. Examples include drug fever and erythema multiforme minor and major (Stevens-Johnson syndrome) and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Reactions due to the production of antibodies or cytotoxic T cells directed against the drug or a biotransformation of the drug.

Pathophysiology

- Mechanism of drug allergy:

- The majority of the therapeutic agents are low molecular weight organic compounds and are not capable of inducing the production of either antidrug antibodies or T-cell proliferation. It is only when the drug (or its biotransformation products) reacts covalently with a tissue protein (or carbohydrate) that acts as a hapten that it is capable of inducing an immune response.

- The actual immunogen may be the hapten itself, the hapten-protein conjugate, or a tissue protein that has been altered by interaction so that it is now recognized as a foreign body.

- Because a chemical bond must occur between the drug and the tissue protein, the propensity of that drug to bind to protein determines the allergenic potential of that drug. Thus, β-lactam antibiotics are very reactive with tissue protein and are major allergens, whereas cardiac glycosides are very nonreactive, and true allergy to this class of drugs is rarely seen.

- The majority of the therapeutic agents are low molecular weight organic compounds and are not capable of inducing the production of either antidrug antibodies or T-cell proliferation. It is only when the drug (or its biotransformation products) reacts covalently with a tissue protein (or carbohydrate) that acts as a hapten that it is capable of inducing an immune response.

- Route of administration is important in the induction phase of drug allergy.

- Parenteral administration of a drug has the highest potential for inducing an immunologic reaction.

- Oral administration is much less likely to result in an immunologic reaction to a drug.

- Application of a drug to the skin may result in a contact sensitivity (type IV) rather than the production of antidrug IgE.

- Parenteral administration of a drug has the highest potential for inducing an immunologic reaction.

- In all but the rarest cases, the actual immunogen is not known.

- This is important because the development of in vivo tests (skin tests) or in vitro tests (ImmunoCAP) is based on a thorough knowledge of the chemical structure of the allergen.

- For the first-generation β-lactam antibiotics, the immunogens are well described or are surmised from extensive skin testing. Seventy five percent of patients with a history of penicillin reaction have a positive skin test result to penicilloyl-polylysine (Pre-Pen).

- Other drug classes are being investigated, but the causative allergen in most cases is not known. It is possible to use the native drug as an allergen in the hope that the drug or its metabolite will provide an appropriate allergenic structure; however, the predictive value of these tests is questionable.

- This is important because the development of in vivo tests (skin tests) or in vitro tests (ImmunoCAP) is based on a thorough knowledge of the chemical structure of the allergen.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- The drug or drugs that the patient had been taking at the time of the reaction. If the reaction occurred in the past, a chart review may be necessary.

- The type of reaction and the potential for that reaction to be immunologic in nature. It is often helpful for the physician to make a list of the potential offending drugs and then to rank the drugs by allergenic potential.

- The severity of reaction is also very important, as it determines the steps that may have to be taken to abrogate a similar reaction. An anaphylactic reaction is much more significant than a minor skin rash.

- A history of reactions to drugs is very helpful. Several groups have demonstrated that a patient who has reacted to one drug is more likely to react to another when compared to a patient who has never reacted. For some patients, true reactions are seen to multiple drug classes and probably represent an increased ability to react to haptenated proteins. This has been referred to as the multiple drug allergy syndrome.

- A family history of drug allergy is also a predictive factor. The relative risk of a drug reaction is multifold higher if the patient’s mother or father has also had a drug reaction.

- Finally, the presence of concurrent illness should be established to ensure that the reaction is due to a drug and not from the illness. For example, a facial rash in a patient with lupus erythematosus is most likely the result of the disease process and not a drug reaction.

Diagnostic Testing

- In vivo or in vitro testing:

- Skin testing is the most important technique for the diagnosis of a true drug allergy. Referral to an allergist/immunologist is necessary for skin testing to be performed.

- In the case of penicillin or the first-generation cephalosporins, skin testing is easily performed and highly predictive of an allergic reaction.

- In vitro testing has the same drawback as skin testing, as it relies on knowledge of the allergen.

- These tests are further compromised by the amount of time that is necessary for the test to be performed (usually >24 hours), and, thus, they are not helpful in the acute situation.

- Evidence has demonstrated that skin testing may not be reliable within the first several weeks after a severe drug reaction, and this may be the one situation in which in vitro testing is necessary.

- Skin testing is the most important technique for the diagnosis of a true drug allergy. Referral to an allergist/immunologist is necessary for skin testing to be performed.

- Provocative dose challenge:

- A provocative dose challenge provides a method for determining a patient’s sensitivity to a given drug or drug class and for initiating therapy. Indeed, in practice, this is performed only when a decision to start the patient on the drug has been made.

- The challenge begins with a small (1:100) dose of the drug and proceeds rapidly to higher doses. If the patient tolerates a low dose (0.1 to 1 mg), then increasing doses are given at 15- to 30-minute intervals.

- The provocative dose challenge should be performed in a medical setting, where appropriate resuscitative measures are available.

- A provocative dose challenge provides a method for determining a patient’s sensitivity to a given drug or drug class and for initiating therapy. Indeed, in practice, this is performed only when a decision to start the patient on the drug has been made.

TREATMENT

Alternate Drug Class

- The most effective therapy for drug allergy is the selection of an alternative drug class.

- In most cases, an effective therapeutic agent exists that does not cross-react with the drug to which the patient is sensitive.

- In some cases, an alternative drug may be of the same drug class but lacks a reactive side chain.

- An example is the substitution of lisinopril or enalapril, which does not have a sulfonamide side chain, and of captopril, which contains a sulfonamide.

- Similarly, ethacrynic acid may substitute for furosemide.

- The substitution of an alternative antibiotic, which may differ only in a reactive side chain, is often very effective and precludes the need for skin testing and desensitization.

- An example is the substitution of lisinopril or enalapril, which does not have a sulfonamide side chain, and of captopril, which contains a sulfonamide.

- The selection of an alternative modality is also effective in anaphylactoid reactions.

Provocative Dose Challenge

- This can often be effective when skin testing or in vitro testing is not available.

- The physician should choose the drug class that is least likely to give a positive reaction. For example, patients who have a history of a reaction to a local anesthetic (which almost never causes a true allergic reaction) can receive a provocative challenge with the least reactive group of agents (those that do not contain a paraaminobenzoic acid ester group).

- Because preservatives such as parabens or additional agents such as β-adrenergic agonists can cause reactions, we recommend that the provocative challenge be carried out using preservative-free solutions.

- These are available as obstetric preparations of most local anesthetics. If a small (1 mL) dose of the local anesthetic does not provoke a reaction, this anesthetic can be used without hesitation.

Pretreatment Protocols

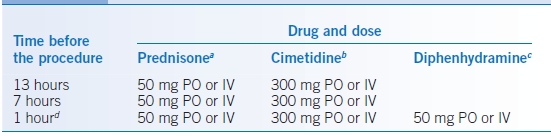

Pretreatment protocols to prevent or temper a reaction are available for a number of drug classes that cause reactions by anaphylactic or anaphylactoid mechanisms. The protocol that is used in the reintroduction of radiocontrast media is presented in Table 39-4.

TABLE 39-4 Protocol for Pretreatment of Patients with a History of Radiocontrast Media Reactions

aOther agents include methylprednisolone, 40 mg IV.

bOther agents include ranitidine, 150 mg.

cOther agents include chlorpheniramine, 10–12 mg.

dCan also add ephedrine, 25 mg PO, 1 hour before procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree