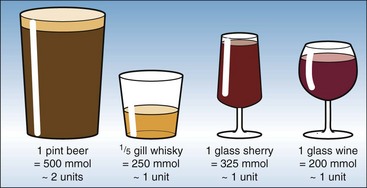

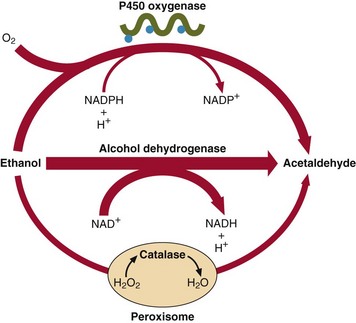

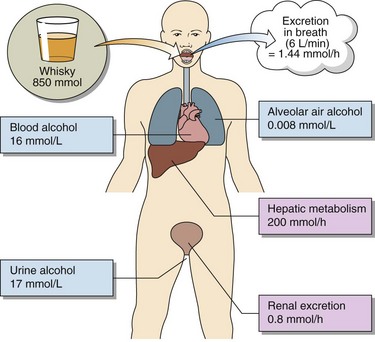

62 Abuse of alcohol (ethanol) is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality, far outstripping other drugs in its effects on the individual and on society. Alcohol is a drug with no receptor. The mechanisms by which it exerts its detrimental effect on cells and organs are not well understood, but the effects are summarized in Table 62.1. Table 62.1 Effects of ethanol on organ systems For clinical purposes alcohol consumption is estimated in arbitrary ‘units’ – one unit representing 200–300 mmol of ethanol. The ethanol content of some common drinks is shown in Figure 62.1. The legal limit for driving in the UK is a blood alcohol level of 17.4 mmol/L (80 mg/dL). Ethanol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by two main pathways (Fig 62.2). The alcohol dehydrogenase route is operational when the blood alcohol concentration is in the range 1–5 mmol/L. Above this most of the ethanol is metabolized via the microsomal P450 system. Although the end product in both cases is acetaldehyde, the side effects of induced P450 can be significant. Ethanol metabolism and excretion in a normal 70 kg man is summarized in Figure 62.3.

Alcohol

System

Condition

Effect

CNS

Acute

Disorientation → coma

Chronic

Memory loss, psychoses

Withdrawal

Seizures, delirium tremens

Cardiovascular

Chronic

Cardiomyopathy

Skeletal muscle

Chronic

Myopathies

Gastric mucosa

Acute

Irritation, gastritis

Chronic

Ulceration

Liver

Chronic

Fatty liver → cirrhosis, decreased tolerance to xenobiotics

Kidney

Acute

Diuresis

Blood

Chronic

Anaemia, thrombocytopenia

Testes

Chronic

Impotence

Metabolism of ethanol

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine