12

AE Volume, Quality, Good Documentation Procedures, and Medical Records

In spite of all the difficulties inherent in the system for collecting and analyzing Adverse Events (AEs), the number of AEs received by companies and health authorities is rising dramatically. This is likely due to several reasons:

- An increased awareness by healthcare practitioners that reporting AEs to the health authorities (and companies) is critical for public health and better communications.

- An increased awareness among patients and consumers of the importance of reporting AEs, at least in the United States, Europe, and Canada, where these reports are encouraged.

- More clinical trials producing more AEs.

- Increasing prescribing of drugs by physicians and the increasing use of drugs by the general population (both prescription and over-the-counter) producing more AEs.

- More toxic (and more efficacious) drugs being produced, treating diseases that, 20 years ago, were badly treated or untreatable by drugs (e.g., AIDS, certain malignancies, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis).

- More drug use by the elderly, more polypharmacy, more drug interactions, and AEs.

- Better communications and easier methods of AE reporting (online, e-mail, EDC, automatic “pulling” of AEs from databases, etc.).

- Better training in pharmacy, nursing, and medical schools as well as increased awareness in hospitals and other healthcare facilities of the need to report AEs.

- People are living longer.

- The spread and use of PV systems to health agencies in countries that either did not have such systems in place or did not pay much attention to them.

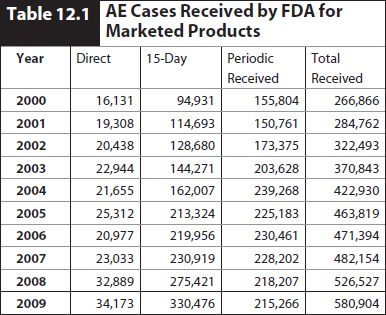

The quantity of AEs received by the FDA on marketed products has increased from 170,000 in 1996 (Goldman and Kennedy, Postgrad Med 1998;103:3) to 580,000 in 2009 (Table 12.1). See FDA’s statistics page (Web Resource 12-1).

In 2009, about 301,000 of the cases were domestic United States cases and about 178,000 were from outside the United States.

It should be kept in mind that non-United States nonserious AEs and non-United States serious-labeled AEs do not have to be reported to the FDA by companies, so the numbers cited above are less than the total AEs captured. These requirements may change in the future.

The FDA expects that manufacturer-submitted MedWatch forms will be complete and of high quality. In its document “Enforcement of the Postmarketing Adverse Drug Experience Reporting Regulations,” September 30, 1999 (Web Resource 12-2), the FDA instructs its inspectors as follows:

Verify the completeness and accuracy of the selected reports against other information in the firm’s files as follows:

- Was information on the form available at the time of submission?

- Was all relevant information included on the form?

- Was the initial receiving date supplied to the agency (FDA Form 3500A Section G Item 4) the same date as the initial receipt of information by the manufacturer?

- Was new information obtained by the firm during the follow-up investigation and was this information submitted to the agency?

- Where feasible, particularly when hospitalization, permanent disability, or death occurred, did the firm obtain important follow-up information to enable complete evaluation of the report?

In addition, the document further instructs the auditor as follows:

Document deviations from the ADE regulations. Clear deviations such as, failure to submit ADE reports, failure to promptly investigate an ADE event, inaccurate information, incomplete disclosure of available information, lack of written procedures or failing to adhere to reporting requirements, should be cited.

These violations are cited in a “483” addressed to the company. More severe violations may produce a “Warning Letter” (see Chapter 48):

The following violations are considered significant to warrant issuance of a Warning Letter:

- Failure to submit ADE reports for serious and unexpected adverse drug experience events (21 CFR 314.80(c)(1) and 310.305(c)).

- 15-day alert reports that are submitted as part of a periodic report and which were not otherwise submitted under separate cover as 15-day alert reports. This applies to foreign and domestic ADE information from scientific literature and postmarketing studies as well as spontaneous reports (21 CFR 314.80(c) (1) and 310.305(c)).

- 15-day alert reports that are inaccurate and/or not complete.

- 15-day alert reports that are not submitted on time.

- The repeated or deliberate failure to maintain or submit periodic reports in accordance with the reporting requirements (21 CFR 314.80(c) (2)).

- Failure to conduct a prompt and adequate follow-up investigation of the outcome of ADEs that are serious and unexpected (21 CFR 314.80(c) (1) and 310.305(c) (3).

- Failure to maintain ADE records for marketed prescription drugs or to have written procedures for investigating ADEs for marketed prescription drugs without approved applications (21 CFR 314.80(i) and 211.198).

- Failure to submit 15-day reports derived from a postmarketing study where there is a reasonable possibility that the drug caused the adverse drug experience.

In other words, the auditors will cite lack of standard operating procedures as well as late, incomplete, inadequately followed-up, or unsent 15-day reports. It thus behooves the company to be sure that quality and compliance procedures are in place to ensure the following:

- All cases are received in the appropriate department in the company. For example, sales representatives and other company personnel, if told about an AE, must report these cases to the drug safety department for the appropriate handling. This must be documented in standard operating procedures, with training provided and documented and violations noted and corrected.

- Cases must be rapidly triaged in the drug safety unit (or elsewhere if appropriate) to ensure that they are handled in the appropriate time frame. This applies most markedly to cases that may be 15-day postmarketing expedited reports (and, of course, those clinical trial cases that may be 7- or 15-day expedited reports). In practice, this means that all serious AEs should reach the drug safety group within 1 to 2 (working) days after receipt anywhere in the company.

- Serious AEs should be promptly entered into the database and medically reviewed, and those cases that are 15-day expedited reports promptly sent to the health agencies. Follow-up should be requested in those cases where there is incomplete information. It is highly unusual for a case to be complete with the initial report, and, in practice, all serious AEs will have follow-up performed.

- Data should be reviewed against the source documents for completeness and accuracy.

- Data should also be reviewed by a physician for medical content.

Audits and inspections performed by the EMA or other European Union health authorities are similar in their fundamental nature but have certain European Union twists that are different from those in the United States (see Chapter 48). In any case, all the points noted above would apply to a European Union audit as well.

Similarly, the European Union, MHRA, and other agencies stress the importance of quality, timeliness, consistency, and the appropriateness of the skill set of the individuals handling particular functions. Volume 9A (Section 2.3.4, “Expedited Adverse Reaction Reporting”) notes that the health agencies (competent authorities) are as follows:

- Monitoring adverse reaction reports received from Marketing Authorization Holders against other sources to determine complete failure to report.

- Monitoring the time between receipt by Marketing Authorization Holder and submission to Competent Authorities to detect late reporting.

- Monitoring the quality of reports. Submission of reports judged to be of poor quality may result in the Marketing Authorization Holders’ follow-up procedures being scrutinized.

- Checking of Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs) to detect underreporting (e.g., of expedited reports).

- Checking interim and final reports of postauthorization safety.

Archiving

Archiving

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree