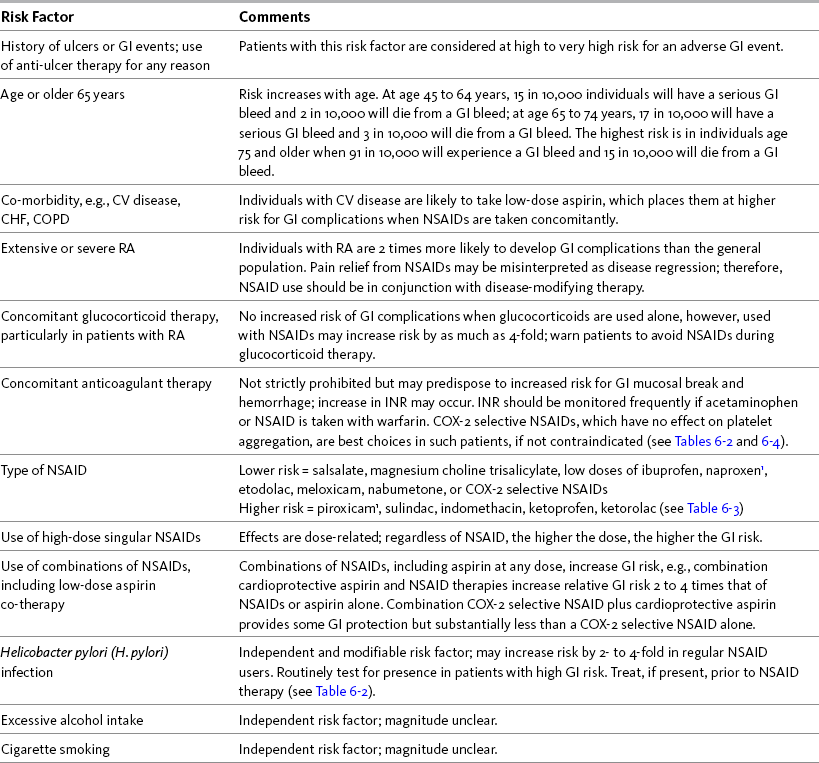

Chapter 6 WITH few adverse effects at doses less than the recommended maximum adult dose of 4 gm per day, acetaminophen is widely considered one of the safest and best tolerated analgesics (Burke, Smyth, Fitzgerald, 2006; Schug, Manopas, 2007). Like other nonopioids, chronic use does not result in tolerance or physical dependence, and carries no risk of respiratory depression. The risk of adverse effects associated with conventional doses of acetaminophen is less than that associated with the other nonopioids (Box 6-1). Although numerous studies have established the potential for acetaminophen toxicity on diverse systems, the likelihood of clinically-relevant adverse effects when this drug is used in appropriate doses is very low. Overall, the risk of adverse effects is greater during treatment with NSAIDs. The positive aspects of NSAID therapy—good effectiveness in many types of common pain syndromes, lack of tolerance or physical dependence, no risk of respiratory depression, and very low risk of typical CNS adverse effects such as somnolence—must be balanced by the potential for serious adverse effects. (See Chapter 8 for a discussion of adverse effects associated specifically with perioperative acetaminophen and NSAID use.) Most experts recommend a reduction in daily dose in individuals who are at high risk for hepatotoxicity (Burke, Smyth, FitzGerald, 2006). For example, the AGS recommends a 50% to 75% reduction in dose in older individuals with hepatic insufficiency (AGS, 2009). Recommendations vary, however. Some authors recommend avoiding acetaminophen entirely in patients with hepatic insufficiency (Bannwarth, Pehourcq, 2003), whereas others suggest that it should be used as the optimal analgesic for patients with stable chronic liver disease (Graham, Scott, Day, 2005). Liver function tests should be performed every 6 to 12 months in any individual at high risk for hepatotoxicity who is taking acetaminophen (Bannwarth, 2006; Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005; Simon, Lipman, Caudill-Slosberg, et al., 2002) (see Chapter 7 for more on acetaminophen dosing). A retrospective review of 1543 patients hospitalized for acetaminophen overdose revealed that 4.5% developed hepatotoxicity despite antidote treatment (n-acetylcysteine) in 38% (Myers, Shaheen, Li, et al., 2008) (see Chapter 10 for more on overdose treatment). While the occurrence of hepatotoxicity was low in this review, the patients who did develop it were 2.5 times more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and 40 times more likely to die in the hospital than those without liver damage. This led researchers to conclude that the nature of most acetaminophen overdoses is relatively benign, but the clinical impact for those who do develop hepatotoxicity is significant. This review also reinforced the impact of known risk factors—34% were alcohol abusers, 13% overdosed accidentally, and 3% had underlying liver disease (Myers, Shaheen, Li, et al., 2008). A significant finding was that the 13% who accidentally overdosed represented 49% of the cases of hepatotoxicity in this study. Co-morbidities were common (82%) in the individuals who overdosed; in addition to liver disease and alcohol abuse, 55% suffered depression. Older age was also identified as a risk factor. The risk of unintentional overdose from acetaminophen mandates that patient teaching be done when prescribing an acetaminophen-containing drug and that this discussion describes safe maximum doses and the types of OTC analgesics and medications, such as cold remedies and sleep aids, that should be avoided (Bataller, 2007; Scharbert, Gebhardt, Sow, et al., 2007) (see Patient Medication Information Form III-4 on pp. 256-257; see Form III-5 on pp. 258-259 for aspirin). In 2009, the U.S. FDA required label changes for acetaminophen and products containing acetaminophen to reflect an increased risk of liver damage under certain circumstances (e.g., maximum daily dose is exceeded, daily intake of three or more alcoholic drinks, preexisting liver disease, concomitant use of other drugs containing acetaminophen) (U.S. FDA, 2009). In addition to product labeling changes, reformulation of acetaminophen-containing opioid analgesics has been proposed to reduce the rising incidence of this preventable form of liver injury (Fontana, 2008). The risk of chronic renal failure also has been linked to long-term acetaminophen use (Bannwarth, 2006) (see Chapter 8 for renal effects in the perioperative setting). The Nurses’ Health Study, established in 1976, utilized questionnaires to evaluate 121,700 female registered nurses for a wide variety of health-related conditions (Colditz, 1995). A cohort (N = 1697) of this study was evaluated later for the effect of acetaminophen, aspirin, or other NSAID use on renal function, as measured by glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (Curhan, Knight, Rosner, et al., 2004). High acetaminophen, but not NSAID or aspirin use, was associated with an increased risk of decline in renal function. Women who used more than 100 gm of acetaminophen over the 11-year collection period had a GFR decline of at least 30%. These studies support the view that acetaminophen can have clinically relevant hematologic effects. It also is true, however, that acetaminophen inhibition of thromboxane A2 is less than that of the nonselective NSAIDs (Munsterhjelm, Niemi, Syrjala, et al., 2003), and studies have shown that surgical bleeding as a result of perioperative acetaminophen intake is low (Ashraf, Wong, Ronayne, et al., 2004; Munsterhjelm, Munsterhjelm, Niemi, et al., 2005) (see Chapter 8 for effect of perioperative nonopioid use on surgical site bleeding). It is probable that the risk of bleeding associated with acetaminophen use is low, but given the extant data, close monitoring of patients receiving acetaminophen and anticoagulation therapy is prudent (Mahe, Bertrand Drouet, et al., 2005, 2006; Ornetti, Ciappuccini, Tavernier, et al., 2005; Parra, Beckey, Stevens, 2007). In 2009, the U.S. FDA required label changes for acetaminophen to advise those who are taking warfarin to discuss the use of acetaminophen with a pharmacist or physician prior to taking acetaminophen (U.S. FDA, 2009). The greatest risk factor for NSAID-associated GI events is the presence of prior ulcer disease with ulcer complications (Chan, Graham, 2004). The AGS lists current peptic ulcer disease as an absolute contraindication and history of peptic ulcer disease as a relative contraindication to the use of NSAIDs in older adults (AGS, 2009). Other risk factors include age at or older than 60 years, CV disease and other co-morbidities, severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and concomitant treatment with corticosteroids or anticoagulants (Bhatt, Scheiman, Abraham, et al., 2008; Chan, Graham, 2004; Laine, 2001; Simon, 2007; Wilcox, Allison, Benzuly, et al., 2006). Helicobactor pylori (H. pylori) infection, excessive alcohol consumption, and cigarette smoking generally are considered independent and modifiable risk factors, though the magnitude of their effects is unclear (Burke, Smyth, Fitzgerald, 2006; Wilcox, Allison, Benzuly, et al., 2006). In 2009, the U.S. FDA required label changes for NSAIDs to reflect an increased risk of gastric bleeding, particularly in certain populations, including older adults and individuals taking anticoagulants, steroids, or other NSAID-containing products, or those consuming three or more alcoholic drinks daily (U.S. FDA, 2009). Table 6-1 provides a summary of risk factors for the development of NSAID-induced GI adverse events. Table 6-1 Risk Factors for NSAID-Induced Adverse GI Events 1Avoid full-dose naproxen, piroxicam, and oxaprozin in older adults because of long half-life and increased risk of GI toxicity. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 192, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2007). Choosing non-opioid analgesics for osteoarthritis. Clinician’s guide. Available at http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/. Accessed July 24, 2008; American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in the Older Persons. (2009). The pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc, 57(8), 1331-1346; Chan, F. K. L., & Graham, D. Y. (2004). Prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastrointestinal complications—Review and recommendations based on risk assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 19(10), 1051-1061; Chan, F. K. L., Hung, L. C. T., Suen, B.Y., et al. (2004). Celecoxib versus diclofenac plus omeprazole in high-risk arthritis patients: Results of a randomized double-blind trial. Gastroenterology, 127(4), 1038-1043; Fick, D. M., Cooper, J. W., Wade, W. E., et al. (2003). Updating the Beers criteria fo potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Arch Intern Med, 163(22), 2716-2724; Gabriel, S. E., Jaakkimainen, L., Bombardier, C. (1991). Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med, 115(10), 787-796; Hanlon, J. T., Backonja, M., Weiner, D., et al. (2009). Evolving pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. Pain Med, 10(6), 959-961; Kurata, J. H., & Nogawa, A. N. (1997). Meta-analysis of risk factors for peptic ulcer: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori, and smoking. J Clin Gastroenterol, 24(1), 2-17; Kuritzky, L., & Weaver, A. (2003). Advances in rheumatology: Coxibs and beyond. J Pain Symptom Manage, 25(2S), S6-S20; Laine, L. (2001). Approaches to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the high-risk patient. Gastroenterology, 120(3), 594-606; Laine, L., White, W. B., Rostom, A., et al. (2008). COX-2 selective inhibitors in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 38(3), 165-187; Simon, L. S. (2007). Risks and benefits of COX-2 selective inhibitors. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewprogram/6872/. Accessed April 5, 2007; Simon, L. S., & Fox, R. I. (2005). What are the options available for anti-inflammatory drugs in the aftermath of rofecoxib’s withdrawal? Medscape Rheumatology, 6(1). Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/500056. Accessed April 16, 2005; Solomon, D. H., Glynn, R. J., Rothman, K. J., et al. (2008). Subgroup analyses to determine cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and coxibs in specific patient groups. Arthritis Care Res, 59(8), 1097-1104; Wilcox, C. M., Allison, J., Benzuly, K., et al. (2006). Consensus development conference on the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, including cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme inhibitors and aspirin. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 4(9), 1082-1089. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. The First International Working Party on GI and CV Effects of NSAIDs and Anti-platelet Agents used a comprehensive series of clinical vignettes and possible scenarios to rate the appropriateness of NSAIDs. This group predefined high GI risk as age at or older than 70 years, prior upper GI event, and concomitant use of aspirin, corticosteroids, anticoagulants, or other antiplatelet drugs (Chan, Abraham, Scheiman, et al., 2008). In addition, risk was determined to be higher with specific NSAIDs and with the combination of an NSAID and low-dose aspirin (Laine, 2001; Simon, 2007; Silverstein, Faich, Goldstein, et al., 2000; Vardeny, Solomon, 2008). In a consensus guideline, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), and the American Heart Association (AHA) stated that the use of cardioprotective aspirin (81 mg) is associated with a 2- to 4-fold increase in upper GI adverse events (Bhatt, Scheiman, Abraham, et al., 2008) (see pp. 204-205 for more on cardioprotective aspirin). It is also important to note that any dose of aspirin can cause upper GI adverse events, and because the primary mechanism underlying GI toxicity is systemic rather than local, buffered and enteric-coated formulations do not decrease the incidence (Bhatt, Scheiman, Abraham, et al., 2008; Laine, 2001). These data support the conclusion that H. pylori infection is an independent and modifiable risk factor for GI complications in long-term NSAID users (Chan, To, Wu, et al., 2002; Huang, Sridhar, Hunt, 2002; Kurata, Nogawa, 1997; Laine, 2001; Wilcox, Allison, Benzuly, et al., 2006). Although it may be difficult to justify routinely ruling out H. pylori infection prior to initiating NSAID therapy in patients with low risk, testing should be done routinely in patients with high GI risk (Chan, To, Wu, et al., 2002; Chan, Graham, 2004; Wilcox, Allison, Benzuly, et al., 2006). If H. pylori infection is present, it should be eradicated prior to initiating NSAID therapy (Chan, Graham, 2004; Wilcox, Allison, Benzuly, et al., 2006) (see Table 6-1).

Adverse Effects of Acetaminophen and NSAIDs

Adverse Effects of Acetaminophen

Renal Effects

Hematologic Effects and Anticoagulant Therapy

Adverse Effects of NSAIDs

GI Risk Factors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Adverse Effects of Acetaminophen and NSAIDs

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue