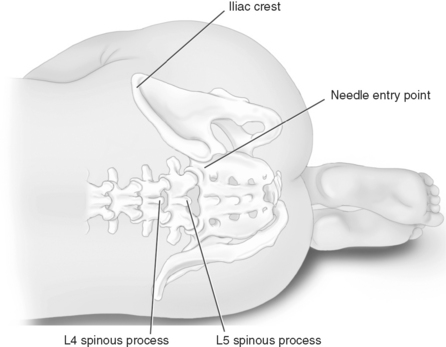

Chapter 26 MANY of the adjuvant analgesics used to treat persistent pain are also used for acute pain. Most are combined with other analgesics as part of a multimodal plan to attack various underlying mechanisms of action (see Chapters 12 and 21 for more on multimodal analgesia). This chapter will present selected adjuvant agents for acute pain, including local anesthetic continuous peripheral nerve block and wound infusion; IV lidocaine; the anticonvulsants gabapentin and pregablin; clonidine; corticosteroids; and ketamine. Antidepressants, which compose another major adjuvant analgesic group, are not discussed here because they have not been shown to be effective for acute pain, including acute experimental pain (Wallace, Barger, Schulteis, 2002), and their delayed onset of analgesia makes them inappropriate for acute pain (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004) (see Chapter 22 for discussion of antidepressantes). See Table V-1, pp. 748-756, at the end of Section V for dosing guidelines and other characteristics of selected adjuvant analgesics. To place a peripheral nerve catheter, the anesthesiologist inserts a needle into the targeted nerve site, injects incremental doses of local anesthetic to block the desired nerve or nerves, and then threads the catheter through the needle (see Figure 26-1 for the site of lumbar plexus catheter placement). The needle is then removed, the catheter is secured, and the site is dressed. In the inpatient setting, continuous peripheral nerve blocks can be administered by the same infusion devices that are used to administer IV PCA or epidural analgesia. In the outpatient setting, portable disposable pumps (elastomeric or vacuum-driven syringe types) are usually used (Skryabina, Dunn, 2006). These latter pumps offer the benefits of being very small and easily discarded after use, avoiding the need for the patient to return the pump and the hospital to develop a pump tracking system. Some pumps allow patient-controlled capability for breakthrough pain so that PCRA may be administered. Some can be programmed to deliver automated bolus delivery in addition to PCRA capability (Taboada, Rodriguez, Bermudez, et al., 2009). The pumps also have simple mechanisms for stopping the infusion if adverse effects occur or at the end of therapy. Catheters are easily removed by clinicians, patients, or family members (Ilfeld, Enneking, 2002; Rawal, Axelsson, Hylander, et al., 1998; Swenson, Bay, Loose, et al., 2006). Nurses are referred to their scope of practice as defined by their individual state board of nursing for their role in the administration of continuous peripheral nerve block, and they should see the American Society for Pain Management Nursing’s Position Paper on the Nurse’s Role in the Management and Monitoring of Analgesia by Catheter Techniques for additional guidance (Pasero, Eksterowicz, Primeau, et al., 2007). See also Box 26-1 for guidelines on the care of patients receiving continuous peripheral nerve block. • Breast surgery (Buckenmaier, Klein, Nielsen, et al., 2003) • Radical prostatectomy (Ben-David, Swanson, Nelson, et al., 2007) • Hand surgery (Rawal, Allvin, Axelsson, et al., 2002) • Wrist, elbow surgery (Grant, Nielsen, Greengrass, et al., 2001; Ilfeld, Morey, Enneking, 2002b) • Shoulder surgery (Borgeat, Kalberer, Jacob, et al., 2001; Borgeat, Perschak, Bird, et al., 2000; Fredrickson, Ball, Dalgleish, 2008; Gottschalk, Burmeister, Radtke, et al., 2003; Grant, Nielsen, Greengrass, et al., 2001; Hofmann-Kiefer, Eiser, Chappell, et al., 2008; Ilfeld, Enneking, 2002; Ilfeld, Morey, Wright, et al., 2003; Ilfeld, Wright, Enneking, et al., 2005; Mariano, Afra, Loland, et al., 2009; Singelyn, Seguy, Gouverneur, 1999; Stevens, Werdehausen, Golla, et al., 2007) • Hip surgery (Chelly, 2007; Hebl, Kopp, Ali, et al., 2005; Ilfeld, Ball, Gearen, et al., 2009; Siddiqui, Cepeda, Denman, et al., 2007; Singelyn, Ferrant, Malisse, et al., 2005; Singelyn, Vanderelst, Gouverneur, 2001) • Knee surgery (Barrington, Olive, Low, et al., 2005; Brodner, Buerkle, Van Aken, et al., 2007; Chelly, Greger, Gebhard, et al., 2001; Dauri, Fabbi, Mariani, et al., 2009; Door, Raya, Long, et al., 2008; Duarte, Fallis, Slonowsky, et al., 2006; Eledjam, Cuvillon, Capdevila, et al., 2002; Fowler, Symons, Sabato, et al., 2008; Grant, Nielsen, Greengrass, et al., 2001; Hayek, Ritchey, Sessler, et al., 2006; Hebl, Kopp, Ali, et al., 2005; Ilfeld, Gearen, Enneking, et al., 2006; Morin, Kratz, Eberhart, et al., 2005; Pulido, Colwell, Hoenecke, et al., 2002; Salinas, Liu, Mulroy, 2006; Syngelyn, Gouverneur, 2000; Zaric, Boysen, Christiansen, et al., 2006) • Lower extremity distal to knee (Ilfeld, Morey, Wang, et al., 2002) • Ankle surgery (Grant, Nielsen, Greengrass, et al., 2001; Ilfeld, Loland, Gerancher, et al., 2008; Ilfeld, Thannikary, Morey, et al., 2004) • Foot surgery (di Benedetto, Casati, Bertini, 2002; Ilfeld, Thannikary, Morey, et al., 2004) • Amputation (Grant, Nielsen, Greengrass, et al., 2001) • Multiple combat casualties, amputation (Stojadinovic, Auton, Peoples, et al., 2006) • Inguinal hernia repair (Schurr, Gordon, Pellino, et al., 2004) • Cancer-related neuropathic pain (Vranken, van der Vegt, Zuurmond, et al., 2001) • Burn pain during skin grafting (Cuignet, Pirson, Boughrouph, et al., 2004) • Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS Type I) (Wang, Chen, Chang, et al., 2001) • Trigeminal neuralgia (Umino, Kohase, Ideguchi, et al., 2002) Epidural analgesia has long been a first-line approach for the management of pain after total knee replacement. A meta-analysis of research comparing peripheral nerve block with epidural analgesia did not distinguish between single-injection and continuous peripheral nerve blocks and emphasized the urgent need for more research comparing the two techniques; the researchers concluded that peripheral nerve blocks appear to represent the best balance between analgesia and adverse effects for major knee surgery (Fowler, Symons, Sabato, et al., 2008). Patients undergoing knee replacement in one study were randomized to receive continuous epidural (ropivacaine + fentanyl) or continuous peripheral nerve block (femoral nerve = ropivacaine + fentanyl; sciatic nerve = ropivacaine) (Zaric, Boysen, Christansen, et al., 2006). Adverse effects, such as sedation and nausea, were more common in the epidural group, but pain was equally well-controlled in both groups, and there were no differences in mobilization and other rehabilitation outcomes or length of hospital stay between the two groups. Another study concluded that IV PCA morphine, continuous femoral nerve block, and continuous epidural analgesia provided similar pain relief, rehabilitation, and hospital stay but recommended continuous femoral nerve block as the best choice following hip arthroplasty given its more favorable adverse effect profile (Singelyn, Ferrant, Malisse, et al., 2005) (see Chapter 17 for IV PCA and Chapter 15 for epidural analgesia). An interesting study used an aggressive multimodal plan that included preoperative and postoperative nonopioid and opioid analgesics; preoperative pericapsular ropivacaine, steroid, and morphine; and epidural anesthesia for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (Dorr, Raya, Long, et al., 2008). Patients were given continuous femoral nerve block (N = 35) or continuous epidural analgesia (N = 35) postoperatively. Those receiving continuous peripheral nerve block consumed less oral opioid; walking distance on day 0 and day 1 was better for patients with epidural analgesia; length of stay was comparable between the groups; and adverse effects and complications were minimal in both groups. No patients had ileus or respiratory depression, which the researchers attributed to the avoidance of parenteral opioids in almost all patients in the study. The most commonly used local anesthetics and concentrations for continuous peripheral nerve block are ropivacaine 0.1% to 0.2% and bupivacaine 0.0625% to 0.125%. (The initial block is established with incremental doses of a higher concentration, usually of the same local anesthetic.) Some clinicians report efficacy with higher concentrations, e.g., a fixed infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine at 5 mL/h (Swenson, Bay, Loose, et al., 2006). One study found that 0.1% ropivacaine provided ineffective analgesia and 0.2% and 0.3% ropivacaine provided similarly effective analgesia (Brodner, Buerkle, Van Aken, et al., 2007). There were no adverse effects among the various concentrations, and the researchers suggested 0.2% concentration at an initial infusion rate of 15 mL/h. Clonidine is sometimes added to peripheral nerve block infusions to enhance the duration and effectiveness of the local anesthetic (Ilfeld, Morey, Enneking, 2003) (see Chapter 22 for more on clonidine). The adverse effects of local anesthetics delivered by continuous peripheral nerve block are similar to those by other routes of administration (see Box 26-1 and Chapter 15). Intravascular catheter migration is rare but has been reported (Capdevila, Pirat, Bringuier, et al., 2005) and would produce signs of local anesthetic toxicity, such as metallic taste, perioral numbness, and tinnitus. Patients receiving this technique should be evaluated systematically for these signs, and those who receive continuous peripheral nerve block in the home setting must be given verbal and written instructions that include the signs and symptoms of adverse effects and what to do if detected (see pp. 757-758 at the end of Section V). Intravascular injection and undetected early signs of local anesthetic toxicity can progress to cardiovascular collapse. Lipid emulsion has been used to successfully resuscitate several patients from cardiac arrest from local anesthetic-induced cardiotoxicity (Clark, 2008); however, the effectiveness of this treatment depends on the type of local anesthetic administered. That is, intralipid treatment appears to be effective for bupivacaine-induced but not ropivacaine- or mepivacaine-induced cardiac arrest (Espinet, Emmerton, 2009; Zausig, Zink, Keil, et al., 2009). Large doses of epinephrine are also reported to be required for reversal of bupivacaine-induced cardiotoxicity (Mulroy, 2002). As mentioned, opioids and nonopioids are often used for breakthrough pain during continuous peripheral nerve block therapy; however, the significant dose-sparing effects of the therapy reduce the incidence of adverse effects associated with these other analgesics, such as GI disturbances from nonopioids, and nausea, sedation, and respiratory depression from opioids. Research suggests that there is less cognitive dysfunction with this technique as well, which has implications particularly in older adult patients (Hebl, Kopp, Ali, et al., 2005). Still, patients must be assessed for these adverse effects whenever these other analgesics are co-administered with the therapy (see Chapters 6 and 19). The use of anticoagulation therapy has significantly improved morbidity and mortality following some major surgeries, such as total knee or hip replacement, but this practice has presented a challenge to those who must find strategies that provide both effective and safe management of the associated pain. Peripheral nerve blocks provide exceptional pain relief but are not without a low risk (0.019% to 1.7%) of nerve damage and deficits from complications (Meier, Buttner, 2007), such as hematoma formation and compression (Siddiqui, Cepeda, Denman, et al., 2007). It is essential that patients be regularly assessed for signs of compression syndrome, such as changes in skin color in the affected area indicating poor circulation or increased numbness, tingling, or weakness in an affected extremity, and to be aware that these may be masked by the effects of local anesthetics (see Box 26-1). The reader is referred to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) guideline for the use of regional anesthetic techniques in anticoagulated patients, which describes the safe use of peripheral nerve blocks in these patients (Horlocker, Wedel, Benzon, et al., 2003) (see Chapter 15 and Table 15-8 on p. 439). As with any indwelling catheter technique, there is a risk of infection and localized inflammation with continuous peripheral nerve blocks. Risk factors include a stay in the ICU with a possible association with catheter placement in patients who have sustained traumatic injury, duration of the indwelling catheter for greater than 48 hours, site of catheter (e.g., higher risk with femoral than with popliteal), male sex, and absence of antibiotic prophylaxis (Capdevila, Bringuier, Borgeat, 2009). Capdevila and colleagues (2009) recommend the same maximal sterile precautions used for epidural cathether placement to anesthesia providers placing peripheral nerve catheters (see Chapter 15). A prospective study of the experiences of nearly 1500 patients who had received continuous peripheral nerve blocks provided bacterial analysis of the catheters placed in 68% of the patients (Capdevila, Pirat, Bringuier et al., 2005). Positive bacterial colonization occurred in 28.7% of the cases, most often from the staphylococcus species (staphylococcus epidermidis [61%], gram-negative bacillus [21.6%], and staphylococcus aureus [17.6%]). The reader is referred to this study for a breakdown of the incidence and type of bacteria depending on type of peripheral nerve block. One patient in this study experienced symptomology from a staphylococcus aureus infection that resolved with antibiotic treatment. Another study found a 57% rate of bacterial colonization (primarily staphylococcus epidermidis) of femoral catheters; three transitory bacteremias occurred but resolved with catheter removal and no antibiotics (Cuvillon, Ripart, Llaourcey, et al., 2001). The authors recommended close monitoring of patients for signs of infection but did not recommend systematic bacterial analysis of catheters (see Box 26-1). Subcutaneous tunneling of the catheter is suggested as a means of further reducing risk, but well-controlled research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of this approach for this purpose (Compere, Legrand, Guitard, et al., 2009).

Adjuvant Analgesics for Postoperative and Other Acute Pain

Continuous Peripheral Nerve Block

Catheter Placement

Research on the Use of Continuous Peripheral Nerve Block

Efficacy Compared with Other Analgesic Approaches

Dosing and Administration Regimens

Adverse Effects and Complications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree