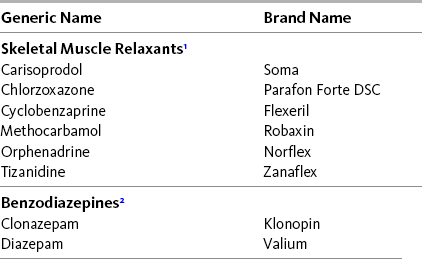

Chapter 25 IN the management of acute traumatic sprains or strains in the nonmedically ill, nonopioid and opioid analgesics are commonly supplemented by treatment with so-called muscle relaxant drugs or benzodiazepines (Table 25-1). Although pains that originate from injury to muscle or connective tissue are also prevalent in medically ill patients, the role of these drugs remains ill-defined. Table 25-1 Adjuvant Analgesics Customarily Used for Musculoskeletal Pain 1No well-controlled studies that show these drugs relax muscle in humans; best viewed as add-on drugs to nonopioid and opioid analgesics. 2Evidence that benzodiazepines relax muscles is limited. Oral clonazepam may be more effective than oral diazepam. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 694, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. The group of drugs known as skeletal muscle relaxants are a heterogeneous group of drugs that are not chemically related (Chou, Peterson, Helfand, 2004) but are grouped together under this classification because they have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of musculoskeletal conditions or spasticity (Chou, Huffman, American Pain Society [APS], et al., 2007). Two groups must be distinguished. The first are drugs used to treat spasticity from upper motor neuron syndromes, such as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and poststroke syndrome. These drugs include tizanidine [Zanaflex], baclofen [Lioresal], and dantrolene [Dantrium]. The second group consists of drugs used to treat muscular pain or spasms from peripheral musculoskeletal conditions, such as myofascial pain syndrome and mechanical low back or neck pain. This group includes drugs that are antihistamines, such as orphenadrine (Norflex); tricyclic compounds structurally similar to the tricyclic antidepressants, such as cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril); and other types of drugs, such as carisoprodol (Soma), chlorzoxazone (Parafon Forte DSC), methocarbamol (Robaxin), and metaxalone (Skelaxin). Midazolam (Versed) is used primarily for procedural sedation (see Chapter 27). The musculoskeletal relaxants are administered primarily by the oral route. Because they are chemically unrelated, there are differences in efficacy among the various drugs, but comparative research is lacking (Chou, Peterson, Helfand, 2004). See Table 25-1 for examples of skeletal muscle relaxants, Chapter 23 for a more detailed discussion of baclofen, Chapter 22 for tizanidine, and Chapter 31 for antihistamines. The reader is also referred to extensive reviews of the many skeletal muscle relaxants used for spasticity and musculo- skeletal pain (Chou, Huffman, APS, et al., 2007; Chou, Peterson, Helfand, 2004). Evidence that the muscle relaxants used to treat common musculoskeletal pain are analgesic derives from studies of variable quality. Poor methodologic designs, insensitive assessment methods, and small numbers of patients are responsible for the inability to demonstrate high efficacy with muscle relaxants (Chou, Peterson, Helfand, 2004; See, Ginzburg, 2008). A Cochrane Collaboration Review concluded that muscle relaxants provide effective symptomatic relief of acute and persistent low back pain on the short term, but with a high incidence of drowsiness, dizziness, and other adverse effects (van Tulder, Touray, Furlan, et al., 2003). A later review of guidelines for the treatment of low back pain concluded that muscle relaxants offer fair relief of acute back pain, but did not recommend them for long-term use (Chou, Huffman, APS, et al., 2007). The review also noted that tizanidine (which, as discussed in Chapter 22, is an alpha2-adrenergic agonist and a multipurpose analgesic) has evidence of efficacy in low back pain. In contrast, little evidence was found to support the effectiveness of baclofen and dantrolene, the other two drugs approved for spasticity. This review provides diagnostic steps and a decision-making algorithm that help to guide appropriate treatment of acute and persistent low back pain. Orphenadrine is combined with aspirin and caffeine and marketed as an analgesic and muscle relaxant. This drug is derived from diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and acts on multiple targets, including histamine and NMDA receptors, the norepinephrine reuptake system, and voltage-gated sodium channels (see Section I) (Desaphy, Dipalma, De Bellis, et al., 2009). Although these actions have implications for analgesia, further research is needed to more clearly define orphenadrine’s role in pain management. Significant adverse effects, such as anticholinergic effects and the potential for seizures and arrhythmias, limit its use. The muscle relaxant drugs are generally well-tolerated but have sedative effects that may be additive to other centrally-acting drugs, including opioids. Muscle relaxants are not recommended in older adults as this age group has increased sensitivity to the anticholinergic and sedating effects of the drugs, and the muscle relaxant effect may contribute to falls (see Section IV Table 13-4 on p. 336). Anecdotally, some patients report differences among drugs in analgesic efficacy or sedative adverse effects, and it is reasonable to switch to an alternative drug if treatment is initially ineffective. Although the dose-response relationships of the muscle relaxant drugs have not been systematically explored, dose-dependent effects probably exist, and the use of a low initial dose followed by gradual dose escalation can be recommended as a means to identify the most salutary balance between analgesia and adverse effects. Experience with these drugs is too limited to pursue dose escalation beyond the usual recommended range. A report of severe withdrawal syndrome in a patient who abruptly stopped taking carisoprodol after long-term use has led to the recommendation to gradually taper doses before discontinuing treatment (Reeves, Beddingfield, Mack, 2004). This is probably good advice for all of the skeletal muscle relaxants. (See cyclobenzaprine patient medication information, Form V-5 on pp. 765-766, at the end of Section V.)

Adjuvant Analgesics for Musculoskeletal Pain

Skeletal Muscle Relaxants

Adjuvant Analgesics for Musculoskeletal Pain

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree