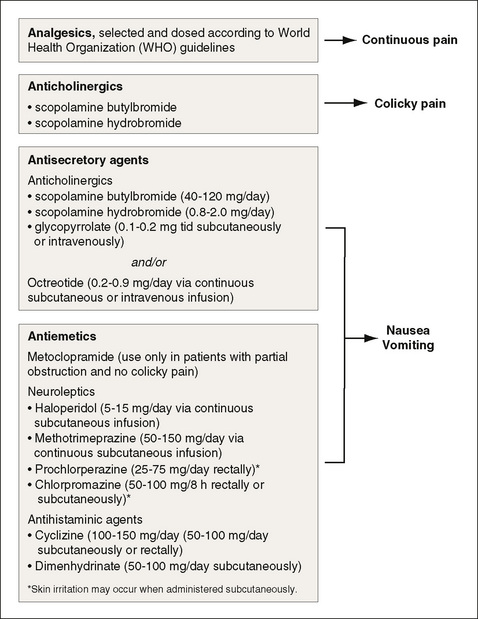

Chapter 30 BOWEL obstruction can occur in any patient with cancer but is most common in those with ovarian or GI cancers (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006). This complication occurs most frequently in the advanced stages of the illness (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). Malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) is caused usually by external compression of the bowel lumen by an adjacent tumor or masses of the mesentery or omentum, or by abdominal or pelvic adhesions. Surgical correction of MBO is usually not an option for patients with advanced cancer (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). If surgical decompression or endoscopic interventions such as stent placement for upper and lower bowel obstructions are not feasible, then the need to control pain and other obstructive symptoms, including distension, nausea, and vomiting, becomes paramount (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006; Davis, Nouneh, 2001; Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). Various analgesics, anticholinergics, antisecretory agents, and antiemetics play important roles (Figure 30-1). If constipation is contributing to the MBO, this must be addressed as part of the approach to symptom management. The first step is to exclude or treat fecal impaction. Unless obstruction is complete, treatment with laxatives should be initiated, and consideration should be given to treatment with an opioid antagonist with limited or no penetration into the CNS (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006). In the United States, methylnaltrexone (Relistor) is now approved for refractory opioid-induced constipation. Oral naloxone or another nonabsorbable opioid antagonist, such as alvimopan (Entereg), also can be considered for this purpose. (See Chapter 19 for more on these drugs for constipation and ileus.) Scopolamine is a commonly used anticholinergic drug (Ripamonti, Mercadante, Groff, 2000) and is available as a transdermal patch, which is a convenient route of delivery in this setting (see Chapter 19 for more on the scopolamine patch). Problematic adverse effects include somnolence or drowsiness, confusion, loss of balance, headache, and dry mouth. These effects typically subside as patients adjust to the medication, but caution is recommended when the drug is used in older individuals who may be more sensitive to some of the effects. Adverse effects usually subside with patch removal. If CNS toxicity is problematic, a trial of an anticholinergic that is relatively less likely to pass through the blood-brain barrier, such as glycopyrrolate (Robinul), is reasonable. Along with antisecretory medications, parenteral hydration over 500 mL/day can help to reduce nausea and drowsiness (Ripamonti, Mercadante, Groff, 2000).

Adjuvant Analgesics for Malignant Bowel Obstruction

Anticholinergic Drugs

Adjuvant Analgesics for Malignant Bowel Obstruction

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree