and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

9.1 Definition, Site and Incidence

Acinic cell carcinoma (ACC) is a neoplasm of low-grade malignancy and composed of cells differentiated towards serous acinar cells. Its original description was provided by Nasse in 1892 [53]. Originally this neoplasm was considered benign and its malignant behaviour was first described in the early 1950’s [13, 36]. Later studies confirmed the malignant potential [1, 33, 37], and its behaviour was regarded to be in between that of adenoma and carcinoma. It was therefore termed acinic cell tumour in the first WHO classification in 1972 [83]. Further series were published that again confirmed the malignant potential [5, 63, 80], and the terminology was correctly revised to acinic cell carcinoma in the second WHO classification published in 1991 [75]. The cells with acinar differentiation contain cytoplasmic zymogen secretory granules and may appear similar to those seen in normal salivary gland tissue or may be vacuolated or may show clear cell differentiation. A fourth cell type present is a non-specific glandular cell. These different cells are arranged in four different growth patterns, microcystic, solid, papillary-cystic and follicular, and combinations thereof [6, 22, 29, 31, 51, 75].

Acinic cell carcinoma is in many studies the third most common major salivary gland malignancy after mucoepidermoid and adenoid cystic carcinoma and represents approximately 15 % of malignant major salivary gland tumours. The vast majority, some 80 %, arise in the parotid glands, whilst it is rare in the submandibular gland where less than 5 % develop. Most of the remaining cases are intraoral and the sublingual gland is involved in less than 1 % of cases. Palatal acinic cell carcinomas are relatively rare. ACC represents approximately 10 % of all malignant tumours in major and minor glands [30, 34, 46, 79, 89]. Similar figures (apart from a much higher incidence of lymphoepithelial carcinoma – 9.7 %) were reported by Wang and co-workers in a recent Chinese study of 289 malignant tumours. The most common cancers were MEC (24.6 %), ADCC (18.0 %) and ACC (12.1 %) [90]. A large Danish study from 2011 comprised 952 cases of major and minor salivary gland cancer during the period 1990–2005 and showed a mean crude incidence of 1.1/100,000/year. The incidences of different subtypes of cancer differed slightly from other studies. Acinic cell carcinoma was the fourth most common malignancy (10.2 %), whereas adenoid cystic carcinoma was the most common (25.2 %), followed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma (16.9 %) and adenocarcinoma NOS (12.2 %). The parotid was the most common site (52.5 %), and 26.3 % of malignancies were located in the intraoral minor salivary glands [9]. Intraoral ACCs are most commonly found in the buccal mucosa, the palate and upper lips [58, 85]. Sinonasal and laryngeal ACCs are very rare [10, 40, 55, 67, 71, 87]. Acinic cell carcinoma has also been reported to develop in the lacrimal gland [44] and lung [21, 49]. A limited number of breast ACCs have been reported [14, 24, 32, 35, 62, 64, 76], and recently also one case has been reported in a BRCA1 mutation carrier [68]. Bilateral acinic cell carcinoma is very rare, and less than 20 cases have been reported [25]. Acinic cell carcinoma is slightly more common in females, but all age groups are rather equally affected, from young children to elderly adults. In the USA, ACC is more common in females than males in the age group under 50 years, but thereafter the incidence rate is almost equal between men and women [11]. Acinic cell carcinoma is in fact after mucoepidermoid carcinoma the most common salivary malignancy in children and approximately 4 % of all ACCs arise in patients under the age of 20 [30, 39, 47, 59, 93]. However, a rather recent retrospective 14-year study from a children’s hospital in New Orleans, USA, identified 13 epithelial salivary gland tumours: 12 pleomorphic adenomas and one acinic cell carcinoma and no mucoepidermoid carcinoma [23]. Only two cases of familial acinic cell carcinoma have been reported in the English literature and hence likely represent coincidental events rather than a manifestation of common genetic or environmental risk [25, 26]. Recently a case of intraoral ACC was reported in a patient where analysis of the PTEN gene identified a germline R130Q mutation in exon 5, hence strongly suggestive of an association of ACC with a PTEN gene disorder (Cowden syndrome) [86].

The entire concept of ACCs arising in non-parotid locations is, however, coming under serious question. The discovery of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma in 2010 (MASC, see Chap. 14) prompted a large retrospective re-evaluation of non-parotid ACCs at the John Hopkins Medical Institutions. The findings are strongly suggestive that most alleged ACCs of non-parotid origin actually represent misclassified MASCs [8]. Further studies are needed to validate the full impact of these findings.

9.2 Clinical Features and Gross Appearances

Acinic cell carcinomas are typically slowly growing masses that on the vast amount of occasions present as a solitary and unfixed parotid lump. They are usually less than 3 cm at presentation but may be considerably larger. On rare occasions, they present as multinodular masses. Only 10 % of ACCs show involvement of the deep lobe of the parotid gland [51]. Facial nerve paralysis is rare and occurs in less than 10 % of cases, but pain is present in as much as a third of cases. The clinical presentation can however be very varied such as an ACC presenting in a child as a large cyst in the submandibular gland [17], a parotid ACC initially presenting with extensive lung metastasis [82] or a parotid ACC presenting as external auditory canal mass [66]. The gross appearance is usually that of a circumscribed nodule with a tan to red cut surface. They can be firm or soft or indeed rather frequently cystic [22, 29, 30, 48, 80].

9.3 Histopathology

Acinic cell carcinoma is one of the salivary gland tumours that most commonly cause diagnostic problems [19]. Four cell types may be present in acinic cell carcinoma. The most typical cells are the acinar cells which are similar in appearance to serous acinar seen in normal salivary tissue. They are relatively large cells with basophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm with numerous dark-staining granules, which are stained red by PAS and resistant to diastase digestion. The nuclei are relatively small and rounded and eccentrically placed. The PAS positivity can be patchy (Fig. 9.1). There are also vacuolated cells containing clear cytoplasmic vacuoles of varying size and number. The vacuoles contain mucopolysaccharides but lack lipids or glycogen and are PAS negative. The vacuolated cells are most frequently seen in microcystic and papillary-cystic types of ACC and less so in solid or follicular variants. The vacuolated cells are unique to ACC amongst salivary gland neoplasms (Fig. 9.2). Clear cells are similar to acinar cells with regard to size and shape, but the cytoplasm is clear and PAS negative, contrary to clear cells of mucoepidermoid carcinoma that are diastase-sensitive PAS positive. This clear cell differentiation is relatively rare and occurs in less than 10 % of ACC, and it never replaces the entire tumour (Fig. 9.3). A fourth non-granular cell type may also be present and may even predominate. They are referred to as non-specific glandular cells and the cytoplasm is often eosinophilic. They tend to have round nuclei and poorly demarcated cell borders. They may develop in syncytial sheets or form duct-like structures. These are the cells that show the most pronounced atypia with prominent nucleoli and mitotic activity (Fig. 9.4). Occasionally differentiated myoepithelial cells are seen, however, likely not part of the neoplasm but rather remnants of the salivary tissue. Calcium deposits are rather frequent and appear both as psammoma-like bodies and as diffuse dystrophic calcifications. The calcifications are often found in a collagenous stroma which can be abundant and hyalinised. Many ACCs are associated with a prominent lymphocytic infiltrate, sometimes with germinal centre formation (Fig. 9.5). The association with lymphoid stroma is, however, nothing unique for ACC but present in several salivary gland tumours [4].

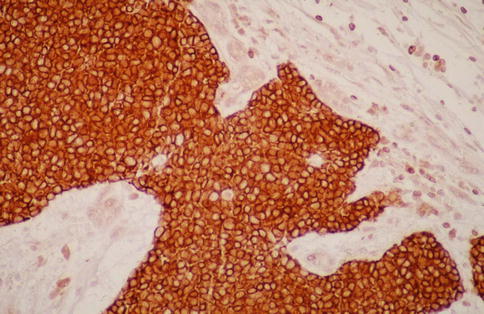

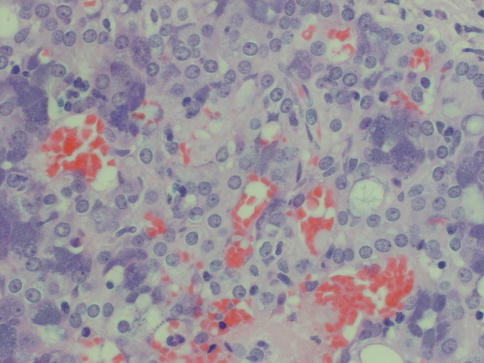

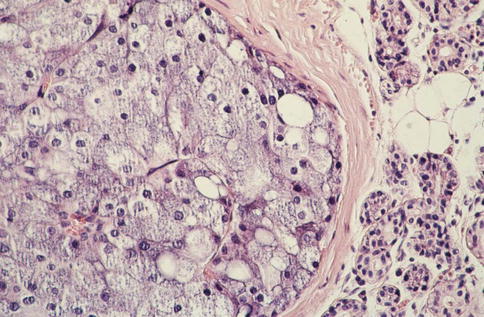

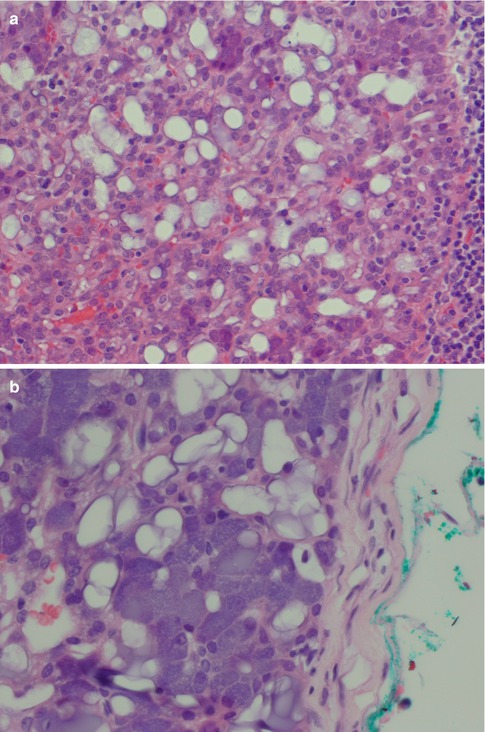

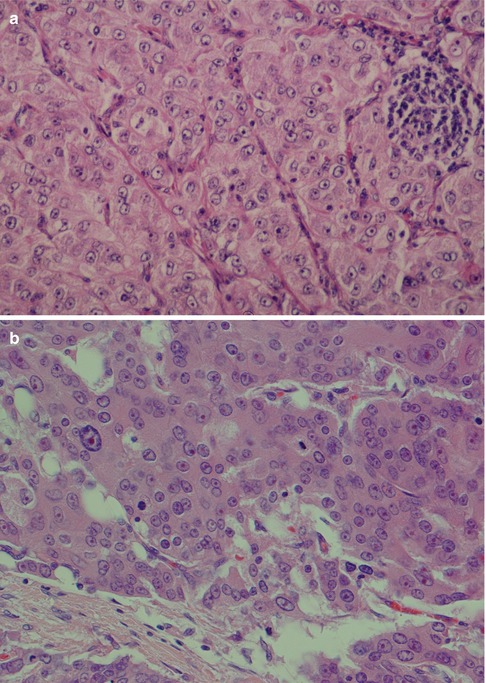

Fig. 9.1

(a) Acinic cell carcinoma composed of granular basophilic cytoplasm. (b) The acinar cells are PAS positive and resistant to diastase digestion (PASD)

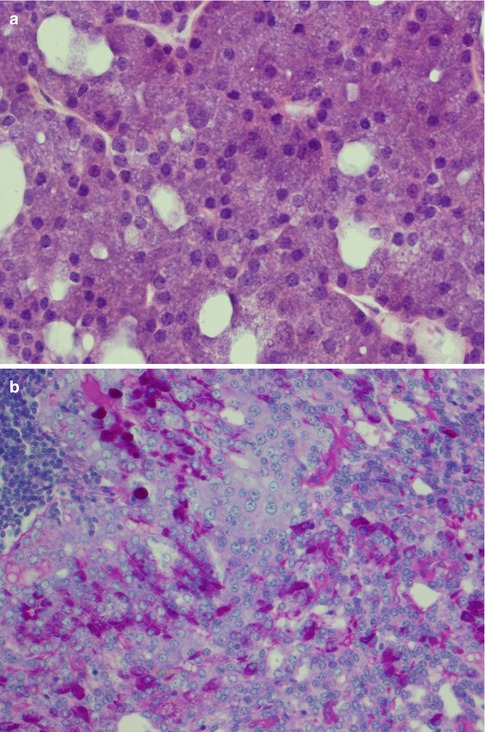

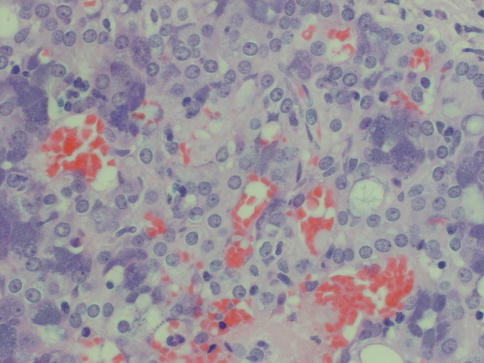

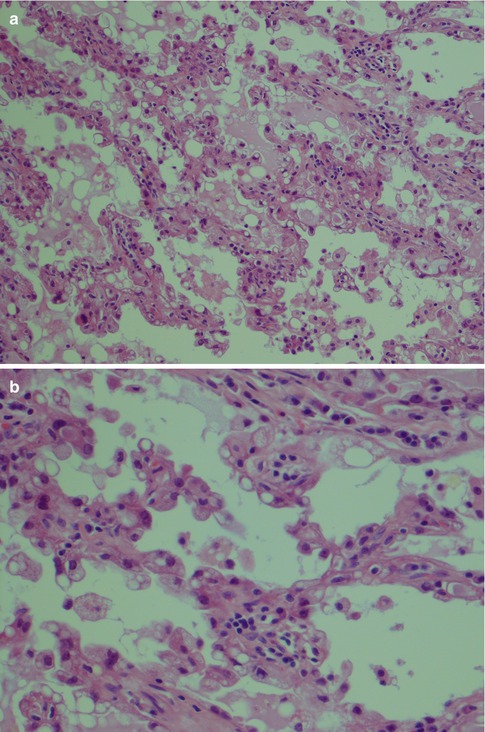

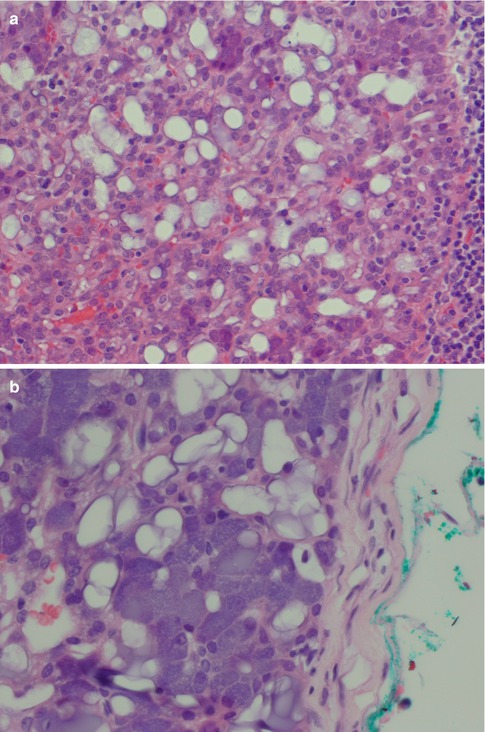

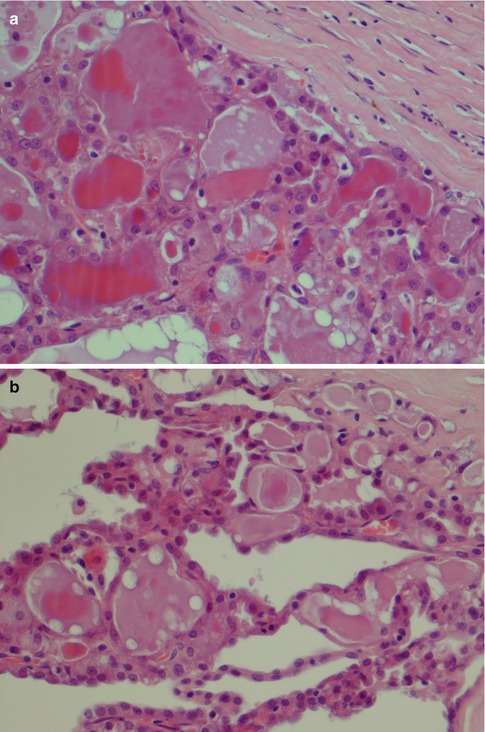

Fig. 9.2

(a) Papillary-cystic ACC with numerous vacuolated cells. (b) Microcystic variant of ACC with vacuolated cells

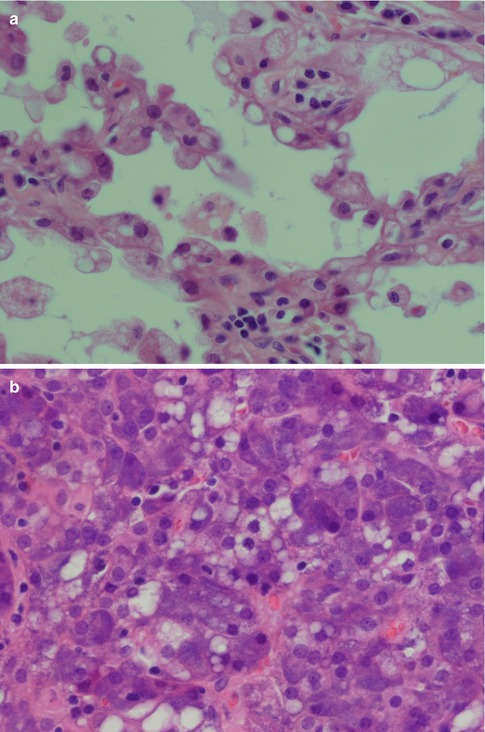

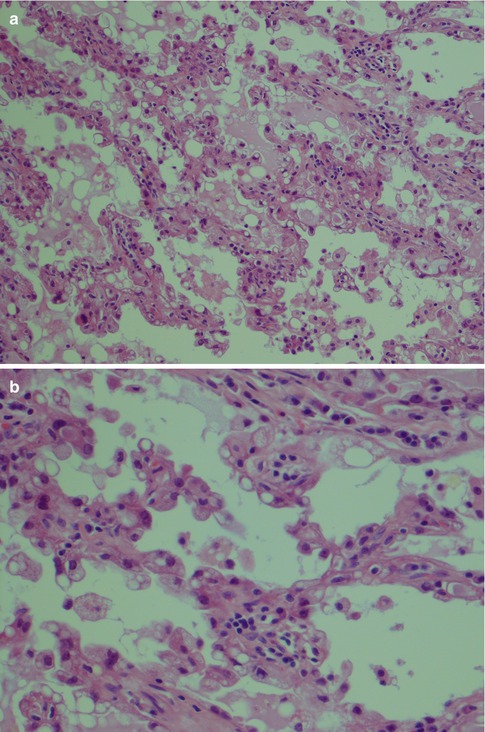

Fig. 9.3

PAS-negative clear cells in an ACC

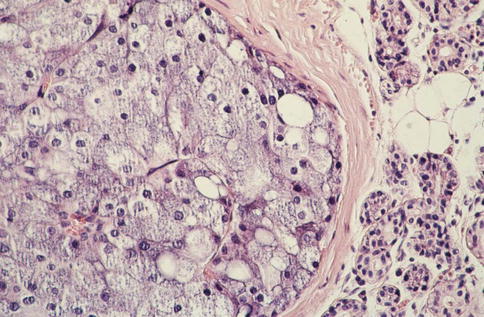

Fig. 9.4

Non-specific glandular cells in the centre surrounded by granular acinar cells. The cells are slightly eosinophilic and arranged in syncytial sheets as well as in a duct-like structure (right)

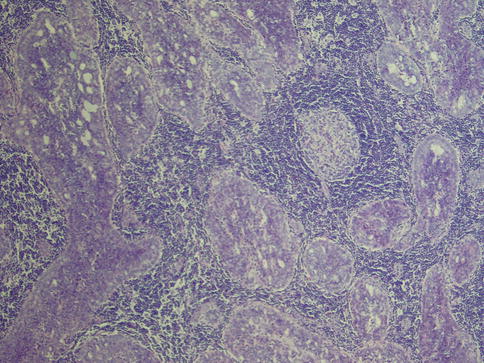

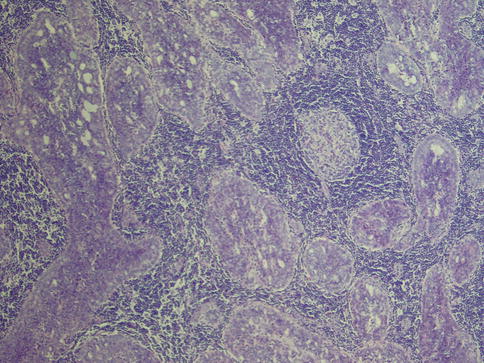

Fig. 9.5

ACC with a prominent lymphocytic infiltrate with germinal centre formation

Rarely does an ACC comprise one growth pattern only, but mixtures of two or more patterns are present. Although these subtypes are histologically recognisable, no prognostic value can be obtained and previous suggestions that the solid variant would have a more aggressive clinical behaviour have not been validated [41, 75]. The most frequently encountered growth patterns are the solid and microcystic patterns. In the solid variant, the neoplasm is composed of well-differentiated and usually uniform basophilic acinar cells. The cells are close together in sheets and nodules or an indefinite arrangement. In spite that ACC is of low-grade malignancy, necrosis is a common finding in the solid variant but is not a sign of more aggressive clinical behaviour as is the case in other salivary gland tumours. Mitotic figures are unusual in all four subtypes (Fig. 9.6). The microcystic variant shows numerous small cystic spaces that vary in size from some microns to several millimetres. The microcysts may be filled with mucinous or proteinaceous material. They probably result from the coalescence of intracellular vacuoles of ruptured cells (Fig. 9.7). The papillary-cystic variant is characterised by cystic spaces that are considerably larger than the microcysts. Papillary epithelial proliferations supported by thin vascular stalks extend into these spaces. This variant is also very vascular and haemorrhage is often a prominent feature. The nuclei do not have ground glass appearance and grooves as seen in metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma, nor does ACC stain positive for TTF-1 or thyroglobulin (Fig. 9.8). The fourth and least common growth pattern is seen in the follicular variant. The structure resembles thyroid follicles with septa of epithelial cells surrounding spaces that contain a homogeneous eosinophilic proteinaceous material. The cells are cuboidal or elongated, and the luminal cell surfaces are convex, imparting a scalloped border to the secreted material. This appearance can be confused with metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma (Fig. 9.9). Calcifications are particularly common in this variant of ACC. On rare occasions, ACC may show extensive neuroendocrine differentiation [69]. The many faces of ACC are becoming increasingly apparent after recognition of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC, see Chap. 14), translocation-associated salivary neoplasms (see Chap. 16) and the use of new diagnostic tools. It appears, for example, that most of zymogen granule-poor ACCs are likely to represent MASC, as may be the cases in most non-parotid ACCs [8, 20, 50, 74, 91].

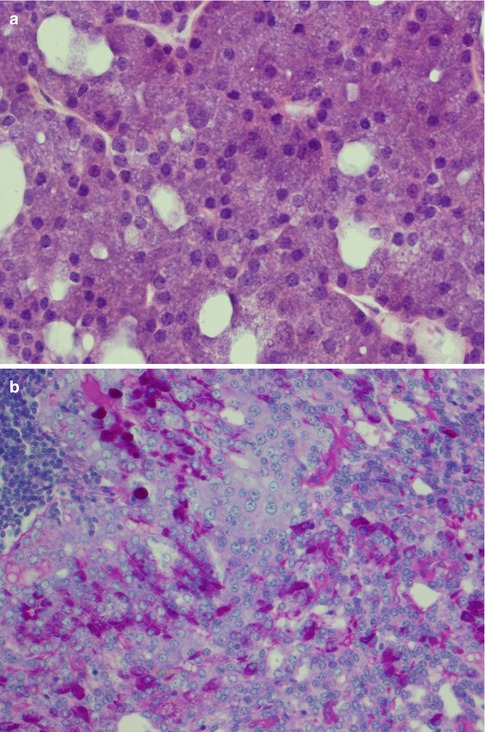

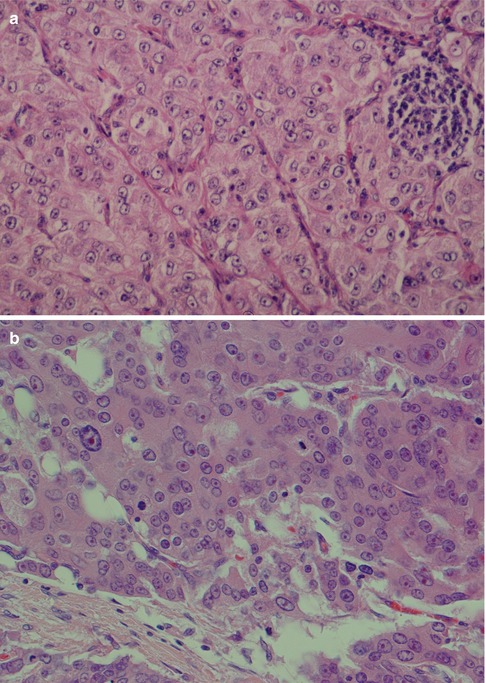

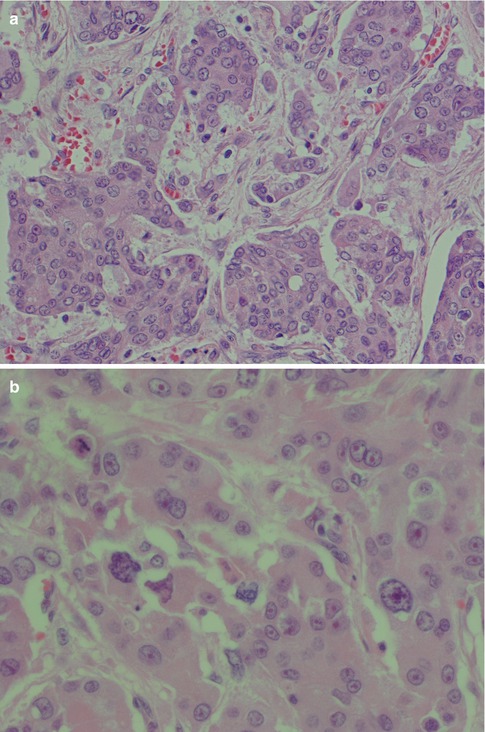

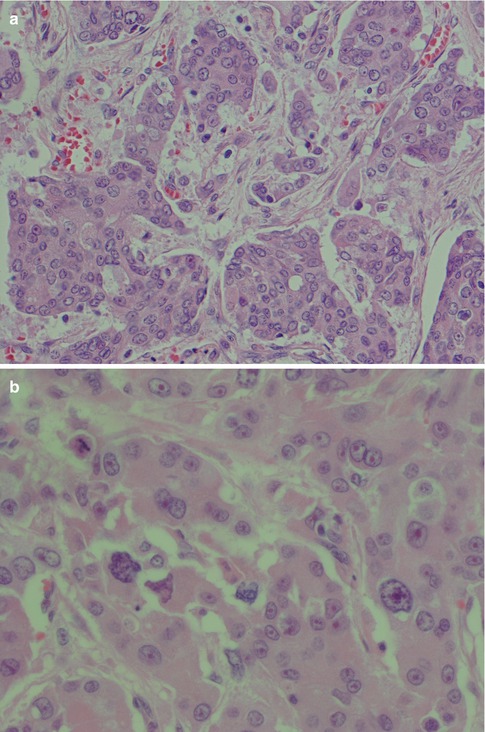

Fig. 9.6

(a) Solid variant of ACC. Note aggregate of lymphocytes. (b) Solid ACC with a few atypical cells with prominent nucleoli

Fig. 9.7

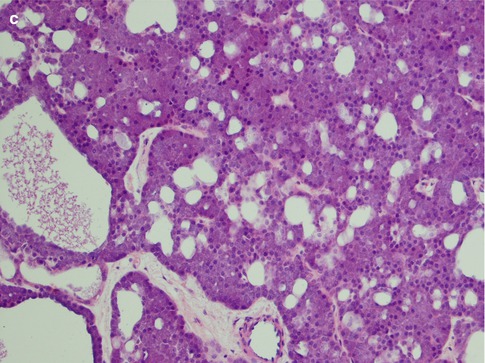

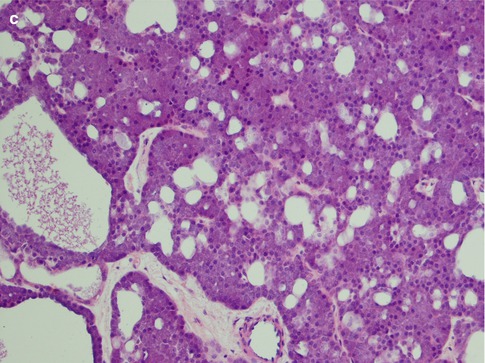

(a) Microcystic variant of ACC with numerous microcysts, also lymphocytes (right). (b) Another microcystic ACC with some vacuolated cells

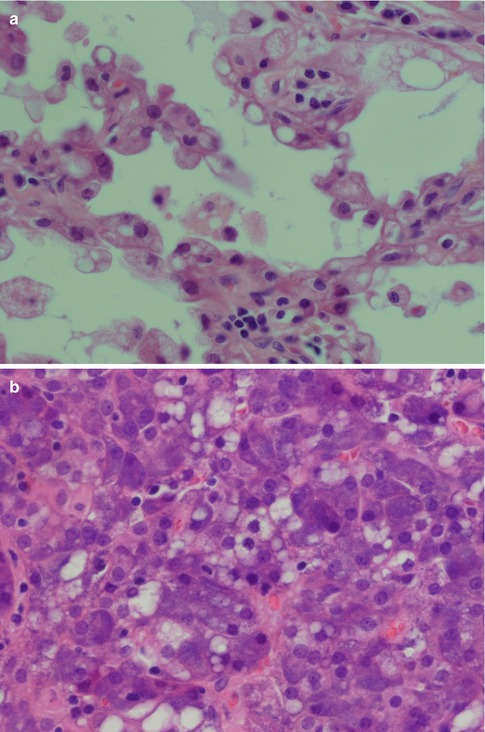

Fig. 9.8

(a) Papillary-cystic ACC with papillary epithelial proliferations. (b) Higher magnification shows some vacuolated cells. The nuclei display no ground glass appearance and no grooves or overlapping. (c) Mixed microcystic and papillary-cystic ACC

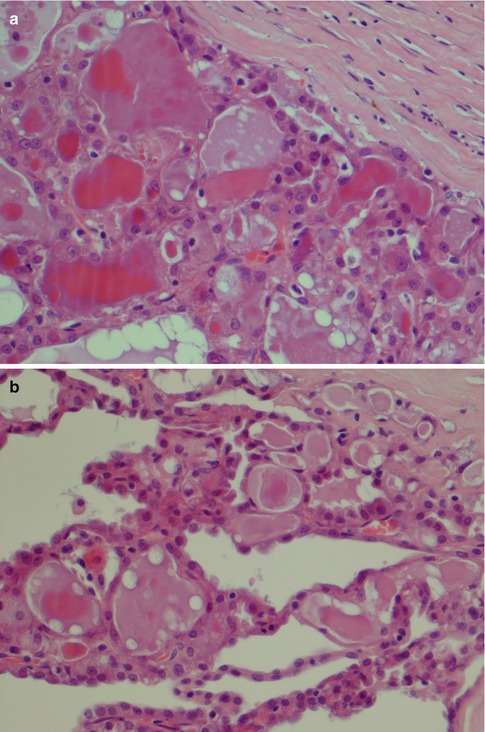

Fig. 9.9

(a) Follicular ACC with thyroid follicle-like appearance. (b) Mixed follicular and papillary-cystic ACC

A possibly distinct subgroup of ACC with almost totally benign clinical behaviour has been described and designated as well-differentiated ACC associated with lymphoid stroma [52]. These tumours are characterised by a microcystic growth pattern surrounded by a dense lymphoid stroma with germinal centres. They have a low Ki-67 labelling index, and the tumours are enveloped by a thin pseudocapsule, hence mimicking a lymph node metastasis. Although few, or no, subsequent reports of this entity are to be found in the literature now 15 years after its description, it may of course still well be a distinct subgroup of ACC.

High-grade transformation (dedifferentiation) from a low-grade to a high-grade malignancy is rare but becoming increasingly recognised (see also Chap. 16) [28, 38, 42, 45, 56, 63, 65, 66, 72, 77, 81]. High-grade transformation in ACC (ACC-HGT) is histologically characterised by both the usual conventional low-grade ACC and a high-grade component with pronounced cellular atypia and increased mitotic figures. It is hence a composite of usual low-grade ACC and high-grade, usually poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma. The two components may be seen in adjacent neoplastic lobules, but there is no significant intermixing of the two neoplastic cell populations. Transitional areas bridging low- and high-grade elements are usually not seen. The relative proportion of low-grade to high-grade in a given tumour varies. ACC-HGT may in some areas mimic a mucoepidermoid carcinoma with solid sheets of almost epidermoid-like cells or even myoepithelial cells; however, usually the features are those of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Fig. 9.10). The high-grade components have high Ki-67 labelling index but TP53 mutations, microsatellite instability and/or loss of heterozygosity at the p53 locus have not been detected [28]. However, high-grade transformation of different (low-grade) salivary malignancies results from numerous mutations involving various genes, and also p53 has been reported in, e.g. adenoid cystic carcinoma [16]. Colmonero and associates [22] described foci of high-grade carcinoma in as much as 8 of 20 cases of ACC emphasising the need for sampling several blocks or, perhaps preferably, the entire tumour. It is hence important to detect any foci of dedifferentiated ACC as this neoplasm is highly aggressive and warrants therapy afforded to high-grade salivary gland carcinoma.

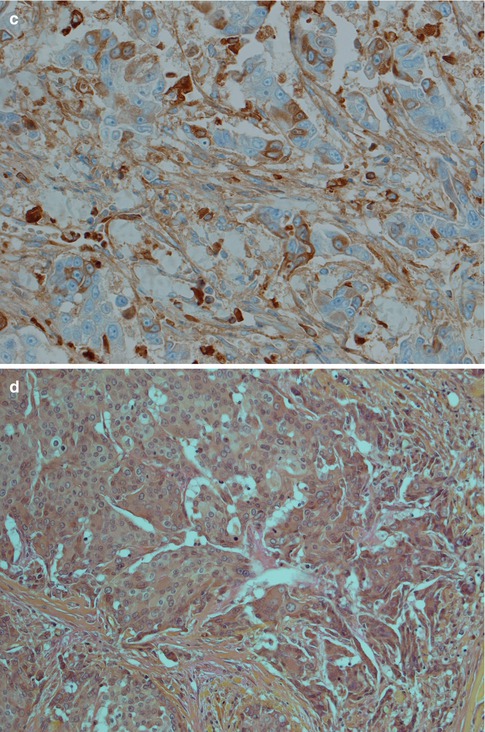

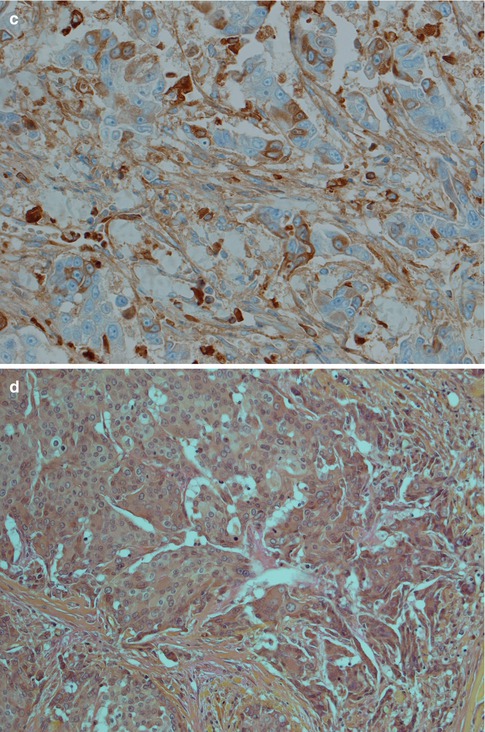

Fig. 9.10

(a) ACC-HGT with features of mucoepidermoid carcinoma (b) Higher magnification showing cellular atypia and atypical mitosis (top left). (c) Scattered positivity for IgA supporting diagnosis of ACC (d) Negative mucicarmine stain favouring ACC-HGT rather than MEC

9.3.1 Immunohistochemistry

Acinic cell carcinoma does not have any unique immunoprofile, but there are a few features that can be of help if the histology is not apparent. CK7 is positive in most ACCs similarly to all other salivary gland tumours but can be patchy and sometimes also reported negative [43]. Low molecular weight cytokeratins, BER-EP4 and CK18 are usually quite strongly positive, whilst high molecular weight cytokeratins show a more patchy and weaker positivity. CK18 often shows a characteristic membranous staining pattern in contrast to a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern seen in many other salivary adenocarcinomas; IgA can be a useful marker being moderately to strongly positive in most ACC. Bcl-2 is usually strongly positive, particularly in solid types of ACC (Fig. 9.11). In a series of 31 ACCs, only four cases were negative for bcl-2 [41]. The diagnostic value is very limited as numerous other salivary gland tumours are bcl-2 positive. CK5/6, CK14, CK20 and CEA are usually negative. P63 is in principal negative. EMA varies from uniform and rather strong positivity to only patchy luminal positivity (Fig. 9.12). Amylase is negative in a very high proportion of ACC because the zymogen granules in many ACC are nonreactive, contrary to normal serous acinar cells. Many ACCs have the non-granular glandular cell as predominant cellular component which contributes to negativity for amylase in ACC. In a series of 47 ACCs, only four showed immunoreactivity for amylase [18]. This is in contrast to acinic cell carcinomas of the breast where the majority appear to stain positively for amylase [24]. Acinic cell carcinomas are reported positive for a number of antibodies, for example, antibodies directed to transferrin, cyclooxygenase-2, alpha 1-antitrypsin, alpha 1-antichymotrypsin, etc. [31]. This may be of limited practical value as many smaller general pathology laboratories may not have these antibodies in-house.