Abnormalities of Mammary Development and Growth

SYED A. HODA

Alterations in mammary development and growth can result in a wide variety of morphologic abnormalities. Most such alterations have genetic bases, which remain, as yet, largely unknown.

HYPOPLASIA AND AMASTIA

The most extreme form of mammary hypoplasia (Greek. hypo: deficient, plasis: molding) is amastia (Gk. a: without, mastos: breast), that is, the complete failure of one or both breasts, including the nipple, to develop.1,2 As one of the least common developmental abnormalities, amastia is encountered more often in females than in males. Familial amastia has been documented in instances in which a brother and sister3 and mother and daughter4 have been affected. It may be accompanied by developmental defects of the ipsilateral shoulder, chest, and/or arm.5 Amastia has been reported in the complex genetic defect of Acrorenal Ectodermal Dysplasia with Lipotrophic Diabetes syndrome.6 In addition to amastia, developmental abnormalities in these young women include skeletal and renal defects and hypodontia.

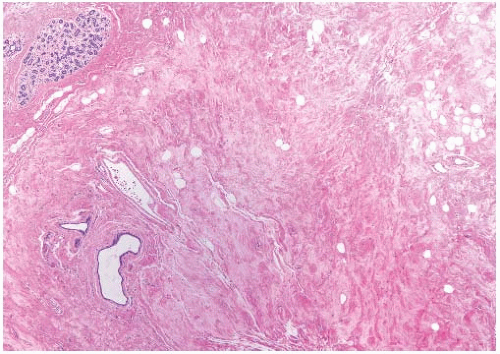

Mammary hypoplasia can occur as a congenital or acquired defect and may be unilateral or bilateral. A diagnosis of unilateral hypoplasia may be made if there is a substantial difference in breast size that far exceeds mild asymmetry and the larger breast is not macromastic. The hypoplastic breast tissue consists of fibrous stroma and ductal structures without acinar differentiation (Fig. 2.1)

Ipsilateral mammary hypoplasia has been reported in conjunction with Becker nevus, a unilateral hairy hyperpigmented lesion,7,8 although breast abnormalities were not described in the original report by Becker,9 an American dermatologist. Concurrent hypoplasia of the ipsilateral pectoralis major muscle has also been reported.10 The pigmented lesions and accompanying mammary hypoplasia occur in males and females.11 High androgen receptor (AR) levels have been detected in Becker nevi7,12 but not in the skin from the unaffected contralateral chest.7

Hypoplasia or aplasia of the mammary glands and hypoplasia of the nipples occur in the Ulnar-Mammary syndrome, a familial genetic abnormality with autosomal dominant inheritance13,14,15 caused by mutations in the TBX3 gene. The latter controls T-box transcription factors,16 which are important in the morphogenesis of multiple organs.17 Commonly associated defects include skeletal abnormalities affecting the ulnar rays of the hands, hypoplasia of apocrine glands, and genital anomalies in males. Poland syndrome, named after Sir Alfred Poland, a surgeon at Guy’s Hospital, London, includes severe congenital defects of the chest and arm combined with mammary hypoplasia, amastia, or athelia.18 Carcinoma can arise in the hypoplastic breast of women with Poland syndrome.19,20

Mammary hypoplasia also occurs in Turner syndrome, named after Henry Turner, an American endocrinologist, and in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Familial hypoplasia of the nipples and athelia (Gk. a: without, thelos: nipple) associated with mammary hypoplasia has been described in a father and his daughters.21 Hosokawa et al.22 described the occurrence of a subcutaneous squamous cyst at the site of unilateral athelia, which suggested that the cystic lesion arose from a maldeveloped nipple.

Acquired mammary hypoplasia has been observed in women who received irradiation of the mammary region in infancy or childhood.23,24 The most frequent clinical reason for radiation in this age group was the treatment of cutaneous hemangiomas. The degree of hypoplasia was directly related to the radiation dose. Unilateral atrophy of a previously normal breast associated with infectious mononucleosis has been described in a 17-year-old girl.25 Biopsy revealed “normal” breast tissue. Surgical excision of the prepubertal breast bud, which enlarges in precocious and early breast development, will result in mammary hypoplasia or amastia by removing part or all of the infantile breast anlage. The occurrence of carcinoma arising in an irradiated hypomastic breast has been reported.26

MACROMASTIA

Several types of excessive breast growth, as assessed by volume and weight, have been described as forms of macromastia (Gk. macro: large, mastos: breast). It has been suggested that macromastia, also referred to as gigantomastia (Gk. gigantikos: giant), should be defined as excess breast tissue that contributes more than 3% of the patient’s total body weight.27 Breast weight is estimated to be 1 g/cm3, but can be rather variable, being mainly density dependent.

Adolescent macromastia occurs as a result of progressive growth over 1 or 2 years during adolescence, resulting

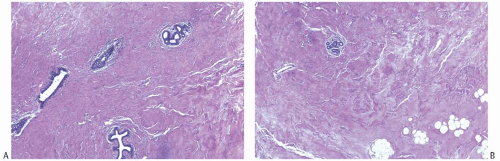

in breast size that far exceeds normal limits. The breasts do not decrease in size in subsequent years, and breast reduction surgery is invariably required. Although the condition is usually relatively symmetrical, there are instances in which there is substantial disparity in breast size. Histologic examination reveals greatly increased stromal collagen and fat (Fig. 2.2). Epithelial hyperplasia of ducts is present in a minority of cases.28 Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is evident in some of these individuals. The stromal cells in one instance of adolescent macromastia, which appears to be PASH in the published illustrations, lacked estrogen receptor (ER) but were positive for progesterone receptor.29 Biochemical ER assays were negative on tissues from a series of 25 patients (ages 17 to 77 years) who had macromastia not associated with pregnancy.30

in breast size that far exceeds normal limits. The breasts do not decrease in size in subsequent years, and breast reduction surgery is invariably required. Although the condition is usually relatively symmetrical, there are instances in which there is substantial disparity in breast size. Histologic examination reveals greatly increased stromal collagen and fat (Fig. 2.2). Epithelial hyperplasia of ducts is present in a minority of cases.28 Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is evident in some of these individuals. The stromal cells in one instance of adolescent macromastia, which appears to be PASH in the published illustrations, lacked estrogen receptor (ER) but were positive for progesterone receptor.29 Biochemical ER assays were negative on tissues from a series of 25 patients (ages 17 to 77 years) who had macromastia not associated with pregnancy.30

FIG. 2.1. Mammary hypoplasia. Breast tissue from a 23-year-old woman with unilateral hypoplasia. A: Ducts that resemble prepubertal breast in collagenous stroma. B: Minimal lobular differentiation. |

Gravid (Gk. gravid: heavy) macromastia develops rapidly, shortly after the onset of pregnancy in the affected individual.31,32,33 It occurs in less than 0.01% of pregnancies.31 The etiology is unknown. Onset very early in pregnancy in some cases has implicated human chorionic gonadotrophin, possibly through a hypersensitivity mechanism. Fetal sex does not appear to be a factor. The majority of women are primiparous, but in some individuals macromastia does not occur until a second or third pregnancy.31,33,34 Once established, the condition is likely to recur in successive pregnancies, even if the pregnancy terminates in a miscarriage. The chance of recurrence is decreased by reduction mammoplasty, but some patients have required further surgery for regrowth of breast tissue after mastectomy.33,35 In one case, gravid macromastia involved bilateral axillary breasts and one ectopic thoracic breast, as well as both normally situated glands.36

A variety of histopathologic changes have been reported in gravid macromastia. Leis et al.34 described a case in which the stroma exhibited “marked fibrosis, with bands of dense collagenous tissue and thickening of the intralobular fibrous tissue.” Thickening of basement membranes was noted, whereas “ducts and acini demonstrated a two-layered epithelium with apparently inactive cuboidal cells.” Fibrosis and collagenization were also noted by Beischer et al.31 and Kullander.37 Others have reported fibroadenomas35,38 and lactational hyperplasia.39 Several authors have commented on the presence of dilated lymphatics in the breast tissue. PASH is often a prominent feature that is evident in retrospect in published illustrations,40 although the condition was not described by this term in the reports (see Chapter 38). Pseudohyperparathyroidism has been associated with gravid macromastia.40 Mastectomy results in prompt remission of the hypercalcemia. Rarely, the clinical presentation of neoplastic conditions such as angiosarcoma or lymphoma in the breast may mimic gravid macromastia.

Mastectomy or breast reduction is usually undertaken after delivery to ameliorate the incapacitating effects of gravid macromastia including pain, depression, and, in some cases, altered pulmonary function. Necrosis of the skin or parenchyma complicated by infection or bleeding may necessitate mastectomy during pregnancy. The concept that hormonal

disturbances contribute to the development of gravid macromastia has led to attempts at endocrine treatment, although none has been uniformly effective. There have not been consistent hormonal abnormalities in patients who were studied, and it appears likely that the fundamental problem lies in abnormal responsiveness of the breast tissues.41 Bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, has been administered, resulting in reduced prolactin levels in some cases but inconsistent clinical responses.37,41,42 Treatment with tamoxifen, a selective ER modulator, was not effective in one case.43

disturbances contribute to the development of gravid macromastia has led to attempts at endocrine treatment, although none has been uniformly effective. There have not been consistent hormonal abnormalities in patients who were studied, and it appears likely that the fundamental problem lies in abnormal responsiveness of the breast tissues.41 Bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, has been administered, resulting in reduced prolactin levels in some cases but inconsistent clinical responses.37,41,42 Treatment with tamoxifen, a selective ER modulator, was not effective in one case.43

Penicillamine-induced macromastia has been reported in patients receiving this penicillin-derived chelating agent for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis,44 and marked breast enlargement or “hypertrophy” has been observed in women with human immunodeficiency virus infection after treatment with indinavir, a protease inhibitor.45

ECTOPIC BREAST TISSUE

The primary milk line develops in the human embryo at 6-week gestation. This line forms a ridge of ectoderm joining the bases of the upper and lower limb buds on either side of the ventral trunk from the mid-axillae through the normal breasts and then inferiorly to the medial groins (Fig. 2.4A).46 Eventually this ridge atrophies except in the thoracic region from which the orthotopic pair of breast originates. It is likely that any persistence of portions of the mammary ridge results in supernumerary breast tissue. In humans, the presence of multiple breasts, which are present in other mammalian species, may be regarded as atavistic—an evolutionary reversion.

Supernumerary breast tissue may assume multiple forms. Such tissue may be with or without glandular tissue, with or without an areola, or as an areola alone. Polythelia (G. polys:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree