Chapter 6. Abdominal

Acute abdominal pain 159

Diarrhoea, vomiting and constipation 169

Gastrointestinal bleeding 174

Abnormal liver function 178

Nutrition 183

Haematuria and urinary retention 185

ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

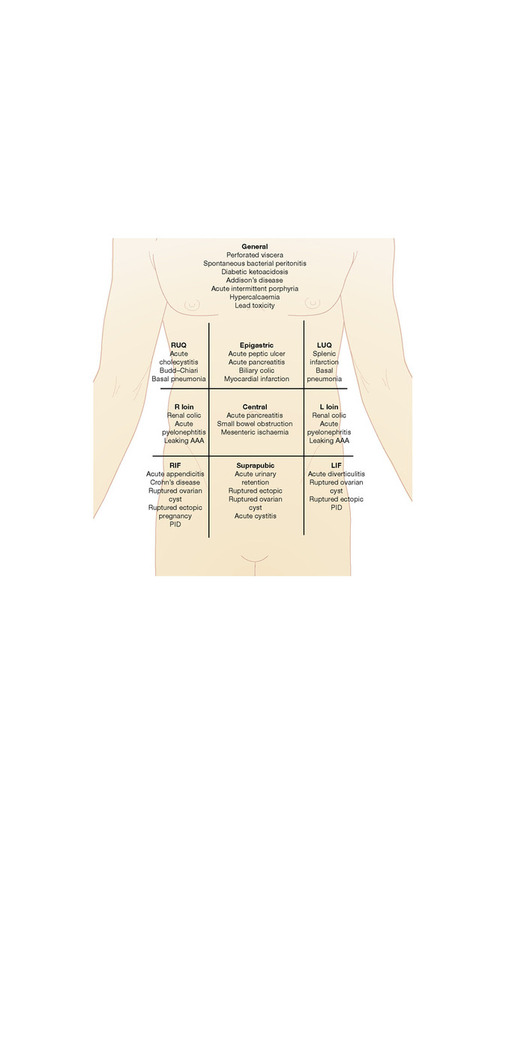

Acute abdominal pain is a common presentation to a variety of hospital specialties including A&E, surgery, medicine and O&G. The wide differential that needs to be considered reflects this variety, as summarized in Figure 6.1. It should be remembered that elderly patients may present with vague symptoms and often have non-specific findings on examination.

|

| Figure 6.1 Causes of acute abdominal pain, by quadrant. |

General assessment

History

Document the nature of the abdominal pain:

• site (including radiation of pain)

• time, mode of onset and duration

• severity and any progression over time

• character, e.g. constant, intermittent, colicky, burning, stabbing, sharp or dull

• exacerbating and relieving factors

• associated features, e.g. nausea, vomiting, weight loss, change in bowel habit, urinary symptoms.

Document when the patient last ate and drank. In all pre-menopausal females, record the date of last menstruation and ask about the possibility of pregnancy. Gynaecological causes of pain should always be considered (see p. 333).

Examination

If the patient is unwell, begin by assessing ABC and looking for evidence of shock (see ‘Shock’, p. 250). Then inspect, palpate, percuss and auscultate the abdomen. Remember to warm your hands before you touch the patient and look specifically for organomegaly, abnormal pulsations or evidence of:

• peritonitis, suggested by rigidity, guarding and absent bowel sounds (absent bowel sounds may also be seen in ileus)

• visceral inflammation or localized peritonitis, suggested by local tenderness with or without rebounding

• obstruction, suggested by abdominal distension, generalized tenderness and tinkling bowel sounds.

Investigations

Investigations should be tailored to the clinical presentation, but the following initial tests should be considered in all patients:

• FBC (WBC may not increase in the elderly), Coag and a G+S

• U&E, LFT, glucose, calcium, amylase (minor elevations common), CRP

• blood cultures if febrile

• ECG

• erect CXR: look specifically for free air under the diaphragm

• supine abdominal film: look for renal calculi, bowel dilatation (>2.5 cm for small intestine and >6 cm for colon) and air in the biliary tree

• urinalysis, including pregnancy test in all females of child-bearing age.

Urgent surgical referral

Patients who are shocked require rapid and adequate fluid resuscitation (see ‘Shock’, p. 250). An urgent surgical opinion should be sought if visceral perforation, generalized peritonitis or bowel obstruction is suspected. All patients should be fasted pending surgical assessment.

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic causes of abdominal pain

Acute cholecystitis, biliary colic and acute cholangitis result from inflammation, infection or obstruction of the biliary tree, usually by gallstones. Gallstones and biliary obstruction can also cause acute pancreatitis. The aetiology, presentation and management of these conditions are outlined below.

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis results from inflammation of the gallbladder wall and, in the majority of cases, is due to impaction of a stone in the neck of the gallbladder or cystic duct.

Presentation and investigation

Patients present with fever and persistent right upper quadrant pain. Murphy’s sign (pain on palpation of the right subcostal region during inspiration) is a useful indicator and is sensitive, but not specific for acute cholecystitis. Acute inflammation of the gallbladder in the absence of biliary calculi (acute acalculous cholecystitis) may occur and is most common in children and adults who have recently undergone severe physical stress (e.g. severe trauma or burns) and are critically ill.

Liver function tests may show an elevated ALP (± bilirubin) and there may be evidence of an inflammatory response. Ultrasound scanning should be performed and may demonstrate the presence of gallstones, a sonographic Murphy’s sign or thickening and dilation of the gallbladder wall.

Management

Appropriate analgesia, intravenous fluids, antibiotics and early referral for cholecystectomy.

Biliary colic

Biliary colic occurs when a gallstone blocks either the common bile duct or the cystic duct.

Presentation and investigation

There is severe, constant right upper quadrant or epigastric pain which usually increases over a 2–4 h period before settling. The pain may radiate to the right shoulder or through to the back and may be triggered by a fatty meal. Pain typically occurs a few hours after a meal and wakes the patient from sleep.

Associated symptoms include nausea, vomiting and fever, although fever with pain for over 24 h is more likely to be due to acute cholecystitis. Murphy’s sign is usually positive during the attack. An ultrasound will identify the presence of gallstones with thickening of the gallbladder wall in the acute phase.

Management

Give appropriate analgesia until pain settles and refer for subsequent cholecystectomy once the acute episode has resolved.

Acute cholangitis

Acute cholangitis results from infection of the biliary tree. In the majority of cases, this is associated with common bile duct calculi, instrumentation of the biliary tree at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or a structural abnormality, such as primary or secondary sclerosing cholangitis.

Presentation and investigation

The classic presentation is with ‘Charcot’s triad’ of fever, jaundice and right upper quadrant pain, but these features may not always be present. Blood tests demonstrate elevation of WBC and CRP and derangement of LFT, often revealing a mixed pattern (see ‘Abnormal LFTs’, p. 178). Amylase may be elevated if there is associated calculi impaction at the ampulla of Vater. Blood cultures are positive in up to 50% of patients.

Management

This should include analgesia, intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, e.g. ceftriaxone 2 g once daily and metronidazole 500 mg 12-hourly. In addition, patients with severe cholangitis and bile duct obstruction require endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

Acute pancreatitis

Presentation

Patients present with severe periumbilical or generalized abdominal pain that often radiates through to the back. Pain may be eased by sitting forward and associated symptoms include nausea and vomiting. There may be fever and/or shock in severe attacks. Periumbilical or flank discoloration (Cullen’s and Grey–Turner’s signs, respectively) may also be seen.

Investigation

Diagnosis is made on the basis of typical clinical features and high serum amylase levels (3–4 times the upper limit of normal). The levels may decline quickly over 2–3 days. Therefore, if a patient presents late, serum amylase levels may be normal or only mildly elevated. However, urinary amylase levels are often high and should be checked. Hyperamylasaemia is not a specific marker of acute pancreatitis and may occur in other conditions, e.g. visceral perforation, small bowel obstruction or ischaemia, leaking aortic aneurysm and MI. Serum lipase is a more specific test and should be used if locally available. All patients should have an abdominal ultrasound performed to visualize the pancreas and biliary tree and exclude gallstones.

The severity of acute pancreatitis should be scored on admission using the modified Glasgow criteria (Table 6.1), Ranson score or APACHE (see p. 11). A CRP level >150 mg/L at 48 h is a reliable marker of a severe attack. Severe acute pancreatitis is associated with acute pancreatic necrosis and may lead to multiple organ failure and/or local complications such as fluid collections, pseudocyst formation, pancreatic abscess, haemorrhage or venous thrombosis. Therefore, in this context, a CT abdomen should be performed.

| ≥3 present within 48 h of admission indicate severe disease. | |

| Variable | Level to meet criteria |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | >55 |

| WBC | >15 × 10 9/L |

| Glucose (if not diabetic) | >10 mmol/L |

| Urea | >16 mmol/L |

| Arterial oxygen partial pressure | <8.0 kPa |

| Calcium | <2.0 mmol/L |

| Albumin | <32 g/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | >600 U/L |

Management

Adequate fluid resuscitation is essential, especially in patients with evidence of shock (see ‘Shock’, p. 250). All patients should be catheterized to allow accurate monitoring of fluid balance, and central venous monitoring is often helpful. In addition, all patients should be managed in a high dependency environment and ICU referral should be considered in severe cases. Pain should be controlled using opiates. A nasogastric tube should be passed if the patient has protracted vomiting, especially if there is an associated ileus. Early nutritional support is recommended for all patients with severe pancreatitis.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

This is defined as an acute bacterial infection of ascitic fluid and may occur in any patient with ascites, regardless of the underlying aetiology. It is associated with a poor long-term outcome in patients with ascites due to liver cirrhosis.

Presentation and investigation

Presentation is variable and approximately one-third of patients are asymptomatic. Fever, mild abdominal discomfort and worsening confusion may be present. However, SBP should be suspected in any patient with liver disease, who presents with an acute deterioration without any obvious precipitant. For this reason, all patients admitted to hospital with ascites should have a diagnostic paracentesis (see ‘Ascitic tap’, p. 46 and ‘Ascitic fluid’, p. 78).

Examination findings vary from normal to overt peritonitis. In severe cases, patients may be haemodynamically compromised and pyrexial. The presence of any stigmata of chronic liver disease or evidence of encephalopathy should be documented. A PR examination should be performed to exclude gastrointestinal bleeding as an additional cause for hepatic decompensation.

Management

Broad-spectrum IV antibiotics should be administered, e.g. ceftriaxone (2 g once daily), metronidazole (500 mg 8-hourly). Careful assessment of intravascular volume state is essential. If there is evidence of shock, treat as advised in ‘Shock’, p. 250. In patients with chronic liver disease and profound hypoalbuminaemia, the use of IV salt-poor albumin should be considered. Antibiotic regimes should be modified once formal bacteriology results are known.

Prophylaxis with norfloxacin (400 mg once daily) is recommended for patients once they have recovered from an acute episode of SBP; however, some gastroenterologists advocate its use in all patients with ascites.

Gastrointestinal causes of abdominal pain

Acute peptic ulcer

This is defined as a break of 3 mm or greater in the mucosa of the stomach or duodenum. It occurs due to an imbalance of damaging factors (e.g. acid secretion, NSAIDs, Helicobacter pylori) and mucosal protective factors (e.g. mucus, bicarbonate, prostaglandins).

Investigation and management

If perforation is suspected, patients should be fasted, receive adequate intravenous fluid resuscitation and early surgical review.

Upper GI endoscopy allows confirmation of the diagnosis, biopsy of potential malignant lesions and testing for H. pylori (CLO test). This should be performed as an inpatient if there as symptoms suggestive of active GI bleeding (e.g. significant haematemesis, or melaena) or malignancy (e.g. weight loss, a palpable abdominal mass or dysphagia).

In other patients, a decision must be made between outpatient endoscopy and an empirical trial of acid suppression therapy. Current guidelines recommend that all patients should be given a trial of acid suppression therapy. If this is unsuccessful they should have non-invasive testing (serological or urea breath testing) for H. pylori infection as a first-line test.

Those with a positive test should receive eradication therapy. Various regimes are available; these generally consist of a high-dose proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and metronidazole, or amoxicillin for 1 week. Eradication should be confirmed, after completion of a course of treatment, by a urea breath test.

Those with a negative test over the age of 55 should have endoscopy, reflecting the higher incidence of stomach cancer in this population (see ‘Stomach cancer’, p. 359).

Bowel obstruction

Bowel obstruction may occur in the large or small bowel. The latter can be classified as complete or partial, and simple (non-strangulated) or complicated (strangulated). Strangulated obstructions are surgical emergencies, as any delay in the diagnosis may lead to bowel ischaemia.

Small and large bowel obstructions differ in regard to their principal causal conditions. The majority of small bowel obstructions occur secondary to herniae or post-surgical adhesions: hernial orifices must be examined thoroughly. Large bowel obstruction is more commonly caused by colonic neoplasms or diverticular disease. However, conditions that can result in either type of obstruction include volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease and impaction with a foreign body (small bowel) or faeces (large bowel).

Presentation

Patients may present with abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and/or constipation. The most prominent features of the history may point to the approximate level of the obstruction, e.g. vomiting alone is a feature of high obstruction. Small bowel obstruction tends to present with colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and, depending on the level of obstruction, constipation. Large bowel obstruction has a similar presentation. However, vomiting is less prominent and, if present, may be faeculant. Suprapubic pain may be associated with constipation.

Investigation

Check FBC, U&E, LFT, Ca 2+ and order an AXR. A supine abdominal X-ray may be helpful in the diagnosis of bowel obstruction and in determining the level of obstruction; see ‘AXR’, p. 101. However, differentiation between strangulation and simple obstruction should be made using clinical parameters, not on abdominal X-ray findings. The level of obstruction can be determined on CT, which may also help to determine the aetiology. Further investigation for large bowel obstruction may include sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

Management

Small bowel obstruction

In cases of partial or simple obstruction, non-operative supportive treatment is sufficient: the obstruction will resolve in the majority of patients within 72 h. Urgent surgical intervention is required for those who fail to respond to non-surgical treatment or where a complete obstruction is present, as the risk of strangulation is high. In cases with an incarcerated hernia, manual reduction should be attempted and, if successful, an elective hernia repair should be arranged as soon as possible.

If obstruction occurs in patients with known inflammatory bowel disease, e.g. Crohn’s disease, initial management should be conservative and include IV steroids (see ‘Crohn’s disease’, p. 166). A barium follow-through or MRI should be performed to fully stage the extent of disease. Surgical input is required if resolution is not rapid, or if long or multiple strictures are present. Treatment options include small bowel resection, with or without stricturoplasty, in combination with immunosuppressive therapy.

Large bowel obstruction

Treatment of large bowel obstruction depends on the cause: neoplastic lesions will need surgical resection or endoscopic stenting. Sigmoid volvulus can be reduced by rigid sigmoidoscopy.

Acute appendicitis

This is defined as an acute inflammatory process within the appendix.

Presentation

The classical presentation is with periumbilical pain which subsequently localizes to the right iliac fossa. Associated symptoms may include anorexia, nausea and vomiting (vomiting generally follows the onset of the abdominal pain). Diarrhoea, constipation or urinary symptoms may also be reported.

Examination findings can be non-specific; however there may be rebound tenderness in the right iliac fossa and voluntary guarding. If perforation has occurred, generalized peritonitis may be present. Other ‘classical’ signs to note are:

• Rovsing’s sign: right iliac fossa pain on palpation of the left iliac fossa

• obturator sign: right iliac fossa pain induced by internal rotation of the flexed right hip.

Investigation

Routine blood tests may reveal a neutrophilia, and CRP will usually be raised. Urinalysis may be abnormal and the diagnosis should not be discarded because of this. Investigation findings may be normal and the diagnosis is often made on clinical grounds. However, if there is diagnostic doubt abdominal imaging, e.g. ultrasound, should be performed. This is particularly the case in women of child-bearing age.

Management

All patients should be fasted until specialist surgical review, while intravenous fluids, antiemetics and analgesia are administered, according to individual requirements. For preoperative wound prophylaxis, metronidazole IV (500 mg 8-hourly) should be used. If the patient is felt to be at risk of abscess or perforation, a broader approach to antibiotic cover is required and ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) should be added.

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract that can affect any mucosal membrane from the mouth to the anus. Unlike ulcerative colitis (see p. 171), Crohn’s is characterized by segmental involvement and involves all layers of the bowel wall.

Presentation

Presenting symptoms in Crohn’s vary considerably and depend on which parts of the bowel are affected. The classical presentation is with fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. An acute presentation may signify a complication, e.g. perforation or abscess formation. A flare of ileo-colic disease may present with fever, right iliac fossa pain, nausea and vomiting (i.e. mimicking acute appendicitis), with or without signs of small bowel obstruction. Occasionally, patients may also present with complications relating to malabsorption, malnutrition or bleeding.

Examination findings may be normal. Low-grade fever and tachycardia are suggestive of active disease. More commonly, there may be mild abdominal tenderness or peritonism. Localized peritonitis may occur; however, generalized peritonitis suggests bowel perforation. Signs of bowel obstruction may also be present. A PR examination should be performed in all patients as perianal disease may be apparent.

Investigation

All patients should have routine haematological and biochemical tests. Elevated WBC and inflammatory markers may signify luminal disease or indicate abscess formation or perforation. Hypoalbuminaemia is a consistent predictor of poor outcome. An AXR should be performed in all patients to exclude colonic dilatation or perforation. An abdominal US is useful to view thickened bowel loops and to localize abscesses.

Management

Acute flares should be treated with IV hydrocortisone (100 mg three times daily) and, if the large bowel is affected, 5-ASA, e.g. mesalazine (400 mg 6-hourly). If patients fail to settle, consider early surgical referral or immunomodulatory therapy such as infliximab. Patients are at an increased risk of thrombosis and, unless otherwise contraindicated, should be commenced on LMWH, e.g. enoxaparin (40 mg SC daily). Once control is achieved, steroid sparing agents such as azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine should be considered. For the management of Crohn’s disease complicated by bowel obstruction, see p. 165.

Acute diverticulitis

Diverticular disease is very common and usually affects the sigmoid colon. Diverticulae are herniations or ‘out-pouchings’ of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis layer and are thought to result from high intra-luminal pressures. Diverticular disease is generally asymptomatic until local inflammation develops (diverticulitis), in response to faecal obstruction of the diverticular neck. Other complications of diverticular disease include pericolic abscess formation, fistula formation (generally occurs between the colon and bladder, uterus, vagina or small bowel), perforation and rectal bleeding.

Presentation

Acute diverticulitis may present with abdominal pain (predominantly left iliac fossa pain), altered bowel habit, PR bleeding, fever, nausea and vomiting. If associated fistulae are present, symptoms may also include pneumaturia, faeculent vaginal discharge or malabsorption.

On examination, patients are often febrile and tender in the left iliac fossa; signs of perforation with or without peritonitis may also be present. Rectal examination may be tender and fresh blood may be seen; a mass may also be palpated.

Management

Fluid resuscitation should be given where the patient is haemodynamically compromised, in addition to analgesia, antispasmodics and broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, e.g. ceftriaxone (2 g once daily) and metronidazole (500 mg 8-hourly). Patients should be advised of the potential benefits of a high-fibre diet. Surgical input is required if the patient fails to respond to medical therapy, or if complications are present.

Vascular causes of abdominal pain

Mesenteric ischaemia

Although this is relatively rare, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Acute mesenteric ischaemia may be thrombotic or embolic in origin. Chronic mesenteric ischaemia is usually related to atherosclerosis. Risk factors include those classically associated with vascular disease, e.g. smoking, diabetes, AF.

Presentation

Acute mesenteric ischaemia classically presents with severe, but poorly localized, abdominal pain, of gradual onset, with vague or no abdominal findings on examination. The pain may be of sudden onset if secondary to arterial emboli.

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia typically results in non-specific abdominal pain, which occurs half an hour after eating. Patients often have associated weight loss, reflecting their reluctance to eat because of pain.

Investigations

In acute mesenteric ischaemia biochemical findings may be non-specific, but patients may have elevated amylase, WBC and a lactic acidosis (particularly associated with infarction). Plain AXR is frequently normal, but may demonstrate mucosal thumb-printing or ‘pneumatosis intestinalis’.

CT abdomen should be considered in patients who are haemodynamically stable. However, mesenteric angiography is often diagnostic and also allows selective thrombolysis.

Management

Treatment options depend on the haemodynamic status of the patient and the underlying suspected aetiology. General measures include oxygen, adequate fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, e.g. ceftriaxone (2 g once daily) and metronidazole (500 mg 8-hourly), and opioid analgesia. A nasogastric tube should be passed if there is an associated ileus and abdominal distension. Early ICU referral should be considered in patients who are haemodynamically unstable.

The surgical team should be involved early; if the patient has signs of peritonitis, urgent laparotomy should be considered. For cases of chronic mesenteric ischaemia, treatment options include angioplasty, stent insertion or formal surgical revascularization.

Ruptured or leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) results from atherosclerotic degeneration of the lining (tunica media) of the arterial walls. Patients are usually asymptomatic until the aneurysm enlarges to such an extent that it causes symptoms related to compression of adjacent structures or ruptures.

Presentation

Examination findings may be normal if the leakage or rupture has been contained by the tamponade effect of a retroperitoneal haematoma. Classical findings of shock and a pulsatile abdominal mass are seen in less than a third of patients.

Investigation

Abdominal CT scanning accurately defines the extent and type of aneurysm and allows assessment of arterial structures involved.

Management

Two large-bore intravenous cannulae should be inserted. Aim for a systolic blood pressure of 100 mmHg. If the patient is hypotensive, fluid resuscitation should be aggressive (see ‘Shock’, p. 251). Where the patient is hypertensive, consider IV β-blockers unless contraindicated. Adequate analgesia should be given and all patients catheterized. Early surgical evaluation is imperative. Treatment should not be delayed for CT scanning.

Renal causes of abdominal pain

Renal colic

Presentation

Renal calculi affect up to 3% of the population. Patients classically present with colicky loin pain, which may radiate to the groin. Associated symptoms include nausea, vomiting, urinary frequency and dysuria.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree