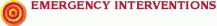

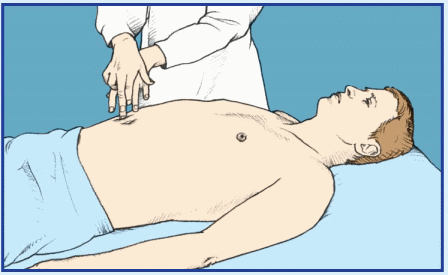

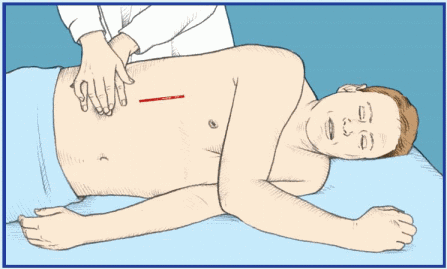

If the patient displays abdominal distention, quickly check for signs of hypovolemia, such as pallor, diaphoresis, hypotension, rapid and thready pulse, rapid and shallow breathing, decreased urine output, poor capillary refill, and altered mentation. Ask the patient if he’s experiencing severe abdominal pain or difficulty breathing. Find out about any recent accidents, and observe the patient for signs of trauma and peritoneal bleeding, such as Cullen’s sign or Turner’s sign. Then auscultate all abdominal quadrants, noting rapid and highpitched, diminished, or absent bowel sounds. (If you don’t hear bowel sounds immediately, listen for at least 5 minutes.) Gently palpate the abdomen for rigidity. Remember that deep or extensive palpation may increase pain.

If the patient displays abdominal distention, quickly check for signs of hypovolemia, such as pallor, diaphoresis, hypotension, rapid and thready pulse, rapid and shallow breathing, decreased urine output, poor capillary refill, and altered mentation. Ask the patient if he’s experiencing severe abdominal pain or difficulty breathing. Find out about any recent accidents, and observe the patient for signs of trauma and peritoneal bleeding, such as Cullen’s sign or Turner’s sign. Then auscultate all abdominal quadrants, noting rapid and highpitched, diminished, or absent bowel sounds. (If you don’t hear bowel sounds immediately, listen for at least 5 minutes.) Gently palpate the abdomen for rigidity. Remember that deep or extensive palpation may increase pain.sure to ask about abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, altered bowel habits, and weight gain or loss.

Umbilical eversion and caput medusae (dilated veins around the umbilicus) are common. The patient may report a feeling of fullness or weight gain. Associated findings include vague abdominal pain, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, bleeding tendencies, severe pruritus, palmar erythema, spider angiomas, leg edema, and possibly splenomegaly. Hematemesis, encephalopathy, gynecomastia, or testicular atrophy may also occur. Jaundice is usually a late sign. Hepatomegaly occurs initially, but the liver may not be palpable in advanced disease.

|

|

|

severe cardiovascular impairment and is confirmed by shifting dullness and a fluid wave. Signs and symptoms of heart failure are numerous and depend on the disease stage and degree of cardiovascular impairment. Hallmarks include peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, dyspnea, and tachycardia. Common associated signs and symptoms include hepatomegaly (which may cause right-upper-quadrant pain), nausea, vomiting, productive cough, crackles, cool extremities, cyanotic nail beds, nocturia, exercise intolerance, nocturnal wheezing, diastolic hypertension, and cardiomegaly.

Major associated signs and symptoms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Common causes | Abdominal mass | Abdominal pain | Abdominal rigidity | Anorexia | Bowel sounds, absent | Bowel sounds, hyperactive | Bowel sounds, hypoactive | Constipation | Diarrhea | Edema | Fever | Hepatomegaly | Hypotension | Jaundice | Jugular vein distention | Nausea | Oliguria | Rebound | tenderness | Succussion splash | Tachycardia | Tachypnea | Urinary frequency | Vomiting | Weight change |

Abdominal cancer | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Abdominal trauma | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||

Bladder distention | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Cirrhosis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

Gastric dilation (acute) | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Heart failure | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||

Irritable bowel syndrome | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Large-bowel obstruction | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Mesenteric artery occlusion (acute) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||

Nephrotic syndrome | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Ovarian cysts | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Paralytic ileus | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Peritonitis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||

Small-bowel obstruction | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||

Toxic megacolon (acute) | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||

or ulcerative colitis that produces dramatic abdominal distention. The distention usually develops gradually and is accompanied by a tympanic percussion note, diminished or absent bowel sounds, and mild rebound tenderness. The patient also experiences abdominal pain and tenderness, fever, tachycardia, and dehydration.

If the patient has a pulsating midabdominal mass and severe abdominal or back pain, suspect an aortic aneurysm. Quickly take his vital signs. Because the patient may require emergency surgery, withhold food or fluids until the patient is examined. Prepare to administer oxygen and to start an I.V. infusion for fluid and blood replacement. Obtain routine preoperative tests, and prepare the patient for angiography. Frequently monitor blood pressure, pulse rate, respirations, and urine output.

If the patient has a pulsating midabdominal mass and severe abdominal or back pain, suspect an aortic aneurysm. Quickly take his vital signs. Because the patient may require emergency surgery, withhold food or fluids until the patient is examined. Prepare to administer oxygen and to start an I.V. infusion for fluid and blood replacement. Obtain routine preoperative tests, and prepare the patient for angiography. Frequently monitor blood pressure, pulse rate, respirations, and urine output.the patient if the mass is painful. If so, ask if the pain is constant or if it occurs only on palpation. Is it localized or generalized? Determine if the patient was already aware of the mass. If he was, find out if he noticed any change in its size or location.

|

left-upper-quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness, splenic friction rub, splenic bruits, and low-grade fever.

If the patient is experiencing sudden and severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs and palpate pulses below the waist. Be alert for signs of hypovolemic shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension. Obtain I.V. access.

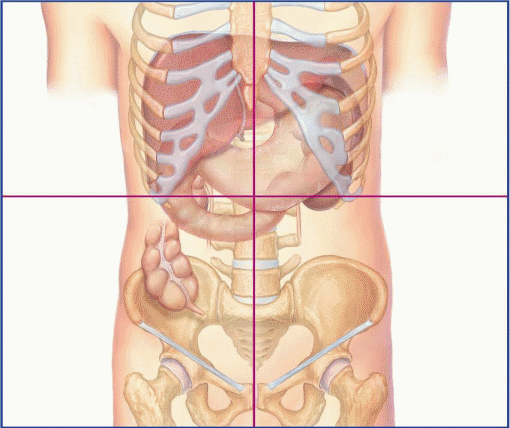

If the patient is experiencing sudden and severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs and palpate pulses below the waist. Be alert for signs of hypovolemic shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension. Obtain I.V. access.Affected organ | Visceral pain | Parietal pain | Referred pain |

Stomach | Middle epigastrium | Middle epigastrium and left upper quadrant | Shoulders |

Small intestine | Periumbilical area | Over affected site | Midback (rare) |

Appendix | Periumbilical area | Right lower quadrant | Right lower quadrant |

Proximal colon | Periumbilical area and right flank for ascending colon | Over affected site | Right lower quadrant and back (rare) |

Distal colon | Hypogastrium and left flank for descending colon | Over affected site | Left lower quadrant and back (rare) |

Gallbladder | Middle epigastrium | Right upper quadrant | Right subscapular area |

Ureters | Costovertebral angle | Over affected site | Groin; scrotum in men, labia in women (rare) |

Pancreas | Middle epigastrium and left upper quadrant | Middle epigastrium and left upper quadrant | Back and left shoulder |

Ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterus | Hypogastrium and groin | Over affected site | Inner thighs |

with guarding, and possibly a palpable mass in a lower quadrant. Abdominal pain is commonly relieved by defecation. Milder chronic signs and symptoms include right-lower-quadrant pain with diarrhea, steatorrhea, and weight loss. Complications include perirectal or vaginal fistulas.

Major associated signs and symptoms | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Common causes | Abdominal distention | Abdominal mass | Abdominal rigidity | Abdominal tenderness | Amenorrhea | Anorexia | Bowel sounds, absent | Bowel sounds, hyperactive | Breath odor, fruity | Chest pain | Constipation | Costovertebral angle tenderness | Cough | Diarrhea | Dyspnea | Fever | Kussmaul’s respirations | Nausea | Oliguria or anuria | Skin lesions | Skin mottling | Tachycardia | Tachynea | Urinary frequency | Vomiting | Weakness | Weight change | |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (dissecting) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Abdominal cancer | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Abdominal trauma | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Adrenal crisis | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Anthrax, GI | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Appendicitis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||

Cholecystitis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Cholelithiasis | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Cirrhosis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Crohn’s disease | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Cystitis | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diabetic ketoacidosis | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diverticulitis | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Duodenal ulcer | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ectopic pregnancy | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Endometriosis | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Escherichia coli O157:H7 | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gastric ulcer | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gastritis | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Gastroenteritis | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Heart failure | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Hepatic abscess | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Hepatic amebiasis | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hepatitis | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Herpes zoster | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Insect toxins | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Intestinal obstruction | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||

Irritable bowel syndrome | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Listeriosis | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mesenteric artery ischemia | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Myocardial infarction | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Norovirus infection | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ovarian cyst | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Pancreatitis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Pelvic inflammatory disease | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Perforated ulcer | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Peritonitis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||

Pleurisy | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pneumonia | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Pneumothorax | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prostatitis | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pyelonephritis (acute) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Renal calculi | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sickle cell crisis | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Smallpox (variola major) | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Splenic infarction | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Systemic lupus erythematosus | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Ulcerative colitis | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||

Uremia | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree