Gynecologic and Obstetric Surgery

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter the reader will be able to:

• Identify the female reproductive anatomy and related structures

• Correlate physiology to conditions requiring surgical intervention

• Identify the disorders and diseases associated with the female anatomy

• Compare diagnostic methods for determination of surgical interventions

• Contrast minimally invasive to open surgical procedures in gynecologic and obstetric surgery

• List the pharmacologic/hemostatic agents in gynecologic and obstetric surgery

• Discuss the patient considerations of both the mother and the baby in Cesarean section

• Review specific procedural steps as a guide for clinical procedure consideration

Overview

Whereas changes in science and technology have impacted every area in medicine over the past century, changes in the specialty of women’s health have had enormous influence over the way women live. At some point in their lives, many women face the prospect of surgery. Surgical procedures on the structures of the female reproductive system are performed for diagnostic, therapeutic, or cosmetic purposes; for conditions such as abnormal bleeding from the reproductive organs; for suspected malignant or benign neoplasms; and for infertility. Procedures are also performed to remove or repair weakened anatomic structures. Recent statistics show the majority of surgical procedures performed in the United States were performed on females (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project [HCUPnet], 2007). A holistic approach with sensitivity to the special needs of this population is an essential component of perioperative care.

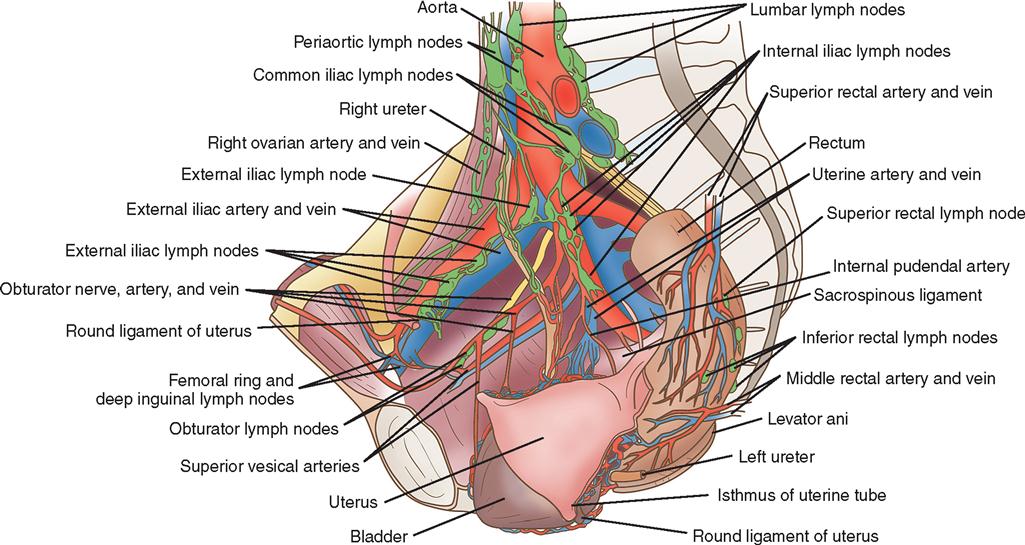

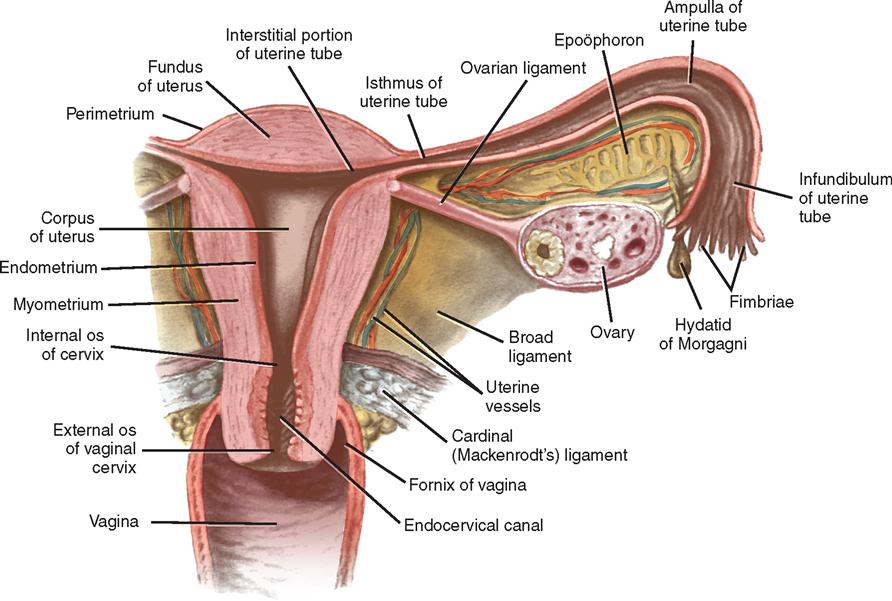

Surgical Anatomy

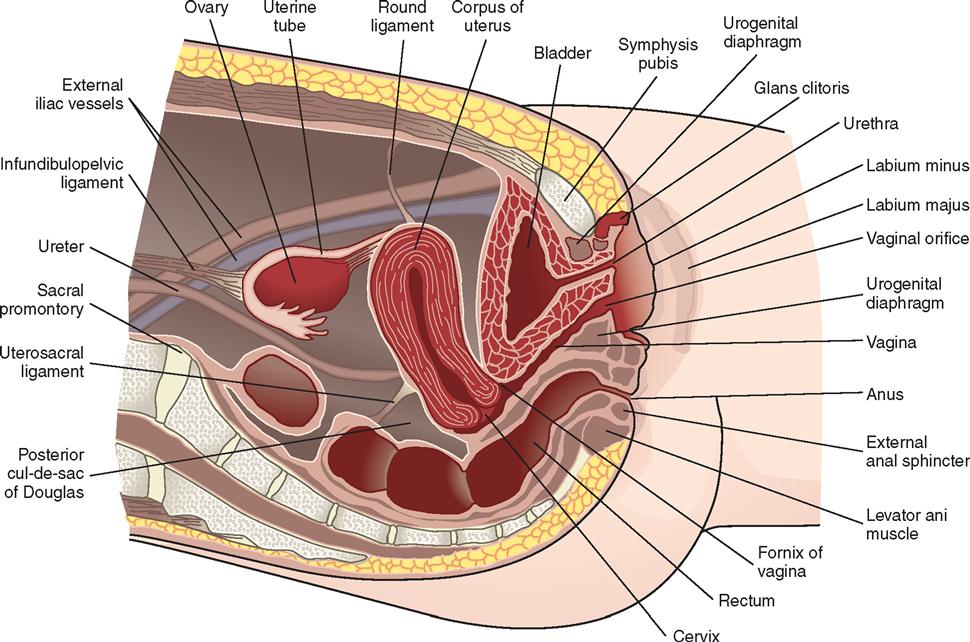

The female reproductive organs and their relationships are shown in Figures 5-1 and 5-2. The adult female structures associated with the process of reproduction are the external organs (vulva), the associated ligaments and muscles, the soft tissues and contents of the pelvic cavity, and the bony pelvis.

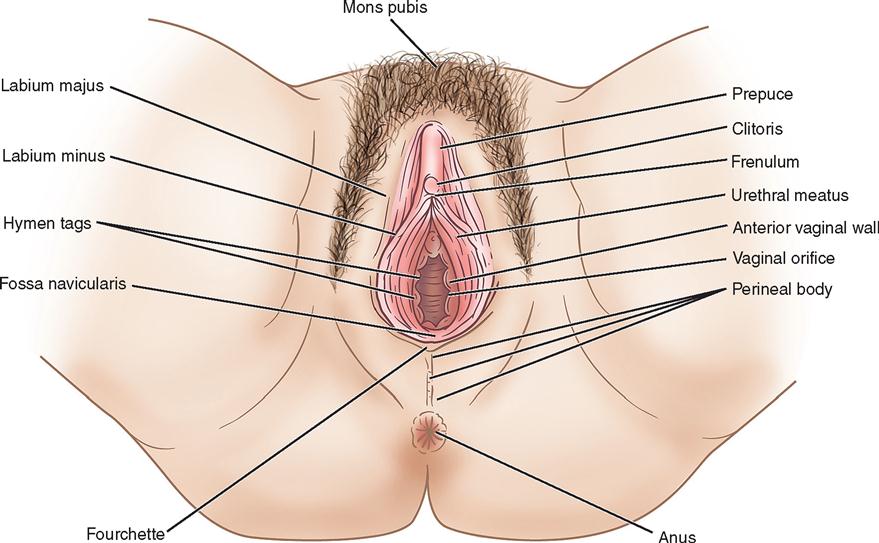

FEMALE EXTERNAL GENITAL ORGANS (VULVA)

The external organs, referred to collectively as the vulva, include the mons pubis, the labia majora and labia minora, the clitoris, the vestibular glands, the vaginal vestibule, the vaginal opening, and the urethral opening (Figure 5-3).

The mons pubis is a mound of adipose tissue covered by skin and, after puberty, by hair. It is situated over the anterior surface of the symphysis pubis.

The labia majora are two folds of adipose tissue covered with skin that extend downward and backward from the mons pubis. Varying in appearance according to the amount of adipose tissue, they unite below and behind the mons pubis to form the posterior commissure and in front of the mons pubis to form the anterior commissure. The labia minora are the two hairless, flat, delicate folds of skin that lie within the labia majora. Each labium splits into lateral and medial parts. The lateral part forms the prepuce of the clitoris, and the medial part forms the frenulum. The posterior folds of the labia are united by a delicate fold extending between them. This forms the fossa navicularis.

The clitoris is the homologue of the penis in the male. It hangs freely and terminates in a rounded glans (small, sensitive vascular body). Unlike the penis, the clitoris does not contain the urethra. The vaginal vestibule is a smooth area surrounded by the labia minora, with the clitoris at its apex and the fossa navicularis at its base. It contains openings for the urethra and the vagina.

The urethra, which is about 4 cm long in the premenopausal woman, is close to the anterior vaginal wall and connects the bladder with the urethral meatus. Two small paraurethral ducts, which are commonly known as Skene’s ducts, lie on either side of the urethral meatus and drain Skene’s glands.

The vaginal opening lies below the urethral meatus. The hymen surrounds the vaginal opening and may be circular, crescentic, or fimbriated.

Bartholin’s glands and ducts are located on each side of the lower end of the vagina. These narrow ducts open into the vaginal orifice on the inner aspects of the labia minora. The glands secrete mucus and can become infected or inflamed.

PELVIC CAVITY

Uterus

The uterus is a pear-shaped organ situated in the pelvic cavity between the bladder and the rectum. It gains much of its support from its direct attachment to the vagina and from indirect attachments to nearby structures, such as the rectum and pelvic diaphragm. The uterus is supported on each side by the broad, round, cardinal, and uterosacral ligaments and levator ani muscles. The upper lateral points, the uterine cornua, receive the fallopian tubes. The fundus of the uterus is the upper, rounded portion positioned above the level of the tubal openings and just below the pelvic brim. Below, the body, or corpus, of the uterus joins the cervix. The corpus is separated from the cervix by a slight constriction (canal) called the isthmus. The cervix lies at the level of the ischial spines. The body of the uterus communicates with the cervical canal at the internal orifice, called the internal os. The constriction (canal) ends at the vaginal portion of the cervix at the external orifice, called the external os. The external os varies in appearance and may be oval, round, slitlike, or everted.

The uterine body has three layers: (1) the outer peritoneal, or serous, layer, which is a reflection of the pelvic peritoneum; (2) the myometrium, or muscular layer, which houses involuntary muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics; and (3) the endometrium, or mucosal layer, which lines the cavity of the uterus.

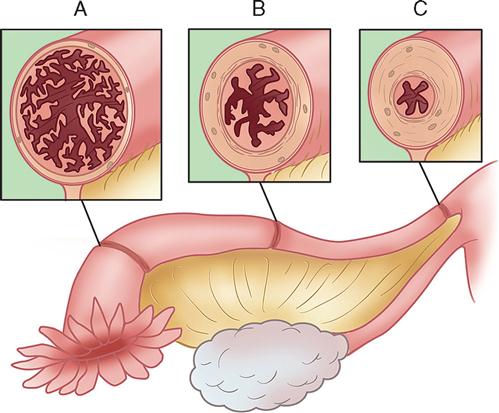

Fallopian Tubes (Oviducts)

The Greek word salpinx, meaning “trumpet” or “tube,” is used to refer to the fallopian tubes (Figure 5-4). The tubes are paired and consist of a musculomembranous channel about 10 to 13 cm long, forming the canals through which the ova are conveyed to the uterus from the ovaries. The outer surfaces of the tubes are covered by peritoneum. The inner layers are composed of muscular tissue lined with ciliated epithelium. Each tube receives its blood supply from the branches of the uterine and ovarian arteries and has four parts. The infundibulum is trumpet-shaped, opens into the abdominal cavity, and has fingerlike projections called fimbriae. The ampulla forms more than half of the tube and is thin-walled and tortuous. The isthmus is cylindric and forms approximately one third of the tube. The remainder of the tube is the uterine portion. Measuring approximately 1 cm in length, it passes through the wall of the uterus.

It has been theorized that the transfer of the ova from the ruptured follicles into the uterus is accomplished through vascular changes that occur with contraction of the smooth muscle fibers of the tube. The peristaltic action of the muscular layer and the ciliary movement propel the ova toward the uterus.

The right tube and ovary are in close relationship to the cecum and appendix; the left tube and ovary are situated near the sigmoid flexure. The fallopian tubes are also in proximity to the ureters.

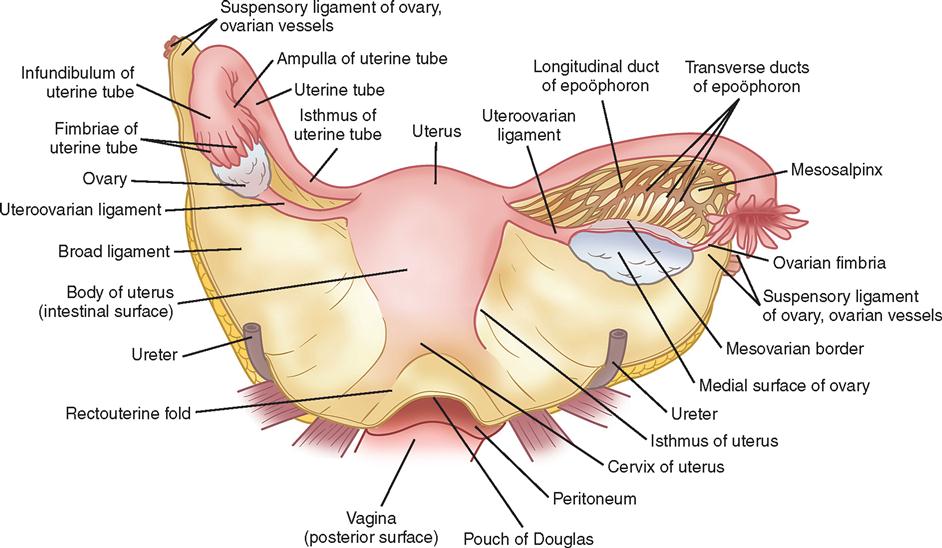

Ovaries

The ovaries are located on each side of the uterus. The ovaries and tubes are collectively known as the adnexa. Each ovary lies within a depression (ovarian fossa) on the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity and above the broad ligament (see Figure 5-5). The anterior border of each ovary is attached to the posterior layer of the broad ligament by a peritoneal fold (mesovarium) and is suspended by the ovarian ligament.

The ovaries are small, almond-shaped organs composed of an outer layer, known as the cortex, and an inner vascular layer, known as the medulla. The medulla consists of connective tissue containing nerves, blood vessels, and lymph vessels. The ovary is covered by epithelium, not peritoneum. The cortex contains ovarian (graafian) follicles in different stages of maturity. After ovulation, the corpus luteum arises from the graafian follicle that expelled the ovum.

The ovaries are homologous with the testes of the male. They produce ova after puberty and also function as endocrine glands, producing hormones such as estrogen, secreted by the ovarian follicles. Estrogen controls the development of the secondary sexual characteristics and initiates growth of the lining of the uterus during the menstrual cycle. Progesterone, which is secreted by the corpus luteum, is essential for the implantation of the fertilized ovum and for the development of the embryo.

Ligaments of the Uterus

The uterine ligaments are the broad, round, cardinal, and uterosacral ligaments (Figure 5-5).

The pelvic peritoneum extends laterally, downward, and posteriorly from each side of the uterus. A double fold of pelvic peritoneum forms the layers of the broad ligament, enclosing the uterus. These layers separate to cover the floor and sides of the pelvis. The fallopian tube is situated within the free border of the broad ligament. The free margin of the upper division of the broad ligament, lying immediately below the fallopian tube, is termed the mesosalpinx. The ovary lies behind the broad ligament.

Round ligaments are fibromuscular bands attached to the uterus. Each round ligament passes forward and laterally between the layers of the broad ligament to enter the deep inguinal ring.

Cardinal ligaments are composed of connective tissue with smooth muscle fibers and provide strong support for the uterus.

Uterosacral ligaments are a posterior continuation of the peritoneal tissue. The ligaments pass posteriorly to the sacrum on either side of the rectum.

Vagina

The vagina is a rugated musculomembranous tube. It carries the menstrual blood from the uterus, serves as the organ for sexual intercourse, and is the terminal portion of the birth canal. The anterior wall measures 6 to 8 cm in length and the posterior wall 7 to 10 cm (see Figures 5-1 and 5-2). The anterior wall of the vagina is in proximity to the bladder and urethra. The lower posterior wall is anteriorly adjacent to the rectum. The upper portion of the vagina lies above the pelvic floor and is surrounded by visceral pelvic fascia. The lower half is surrounded by the levator ani muscles.

Cervix

The cervix consists of a supravaginal portion, which is closely associated with the bladder and the ureters, and a vaginal portion, which projects downward and backward into the vaginal vault. The projection of the cervix into the vaginal vault divides the vault into four regions, called fornices: anterior, posterior, right lateral, and left lateral.

The posterior fornix is in contact with the peritoneum of the pouch, or cul-de-sac, of Douglas. The rectovaginal septum lies between the vagina and rectum. The dense connective tissue separating the anterior wall of the vagina from the distal urethra is termed the urethrovaginal septum.

BONY PELVIS

The pelvis is that portion of the trunk below and behind the abdomen. The bony pelvis is composed of the ilium, symphysis pubis, ischium, sacrum, and coccyx. The so-called pelvic brim divides the abdominal false portion, located above the arcuate line, from the true portion of the pelvis, located below this line. The bony pelvis accommodates the growing fetus during pregnancy and the birth process.

The true pelvis may be considered to have three parts: inlet, cavity, and outlet. The muscles lining the pelvis facilitate movement of the thighs, give form to the pelvic cavity, and provide a firm elastic lining to the bony pelvic framework. All organs located in the pelvis are covered by pelvic fascia, which is extremely important in the maintenance of normal strength in the pelvic floor.

The fascia covering the muscles is usually dense and firm, whereas that covering organs is often thin and elastic. The nerves, blood vessels, and ureters coursing through the anatomic structures are closely associated with muscular and fascial structures.

PELVIC FLOOR

The pelvic floor acts as a supportive sling for the pelvic contents. The pelvic fascia may be divided into three general groups: parietal, diaphragmatic, and visceral. The parietal pelvic fascia covers the muscles of the true pelvic wall and perineum. The diaphragmatic fascia covers both sides of the pelvic diaphragm, which is made up of the levator ani and coccygeal muscles. The visceral fascia is thin and flexible and covers the pelvic organs. The floor of the pelvis, known as the pelvic diaphragm, gives support to the abdominal pelvic viscera in this region. It consists of the levator ani and coccygeal muscles with their respective fascial coverings; it separates the pelvic cavity from the perineum.

The levator ani muscles, varying in thickness and strength, may be divided into three parts: the iliococcygeal, the pubococcygeal, and the puborectal muscles. The fibers of the levator ani muscles blend with the muscle fibers of the rectum and vagina. The pubovaginal fibers of the pubococcygeal portion of the levator ani muscles, lying directly below the urinary bladder, are involved in the control of micturition. The pubococcygeal fibers of the levator ani muscles control and pull the coccyx forward and assist in the closure of the pelvic outlet. The fibers pull the rectum, vagina, and bladder neck upward toward the symphysis pubis in an effort to close the pelvic outlet and are responsible for the flexure at the anorectal junction. Relaxation of the fibers during defecation permits a straightening at this junction. During parturition, the action of the levator ani muscles directs the fetal head into the lower part of the passageway.

Vascular, Nerve, and Lymphatic Supply of the Reproductive System

The blood supply of the female pelvis is derived from the internal iliac branches of the common iliac artery and is supplemented by the ovarian, superior rectal, and median sacral arteries—branches of the aorta.

The nerve supply of the female pelvis comes from the autonomic nerves, which enter the pelvis in the superior hypogastric plexus (presacral nerve). The lymphatics of the female pelvis either follow the course of the vessels to the iliac and preaortic nodes or empty into the inguinal glands (Figure 5-6).

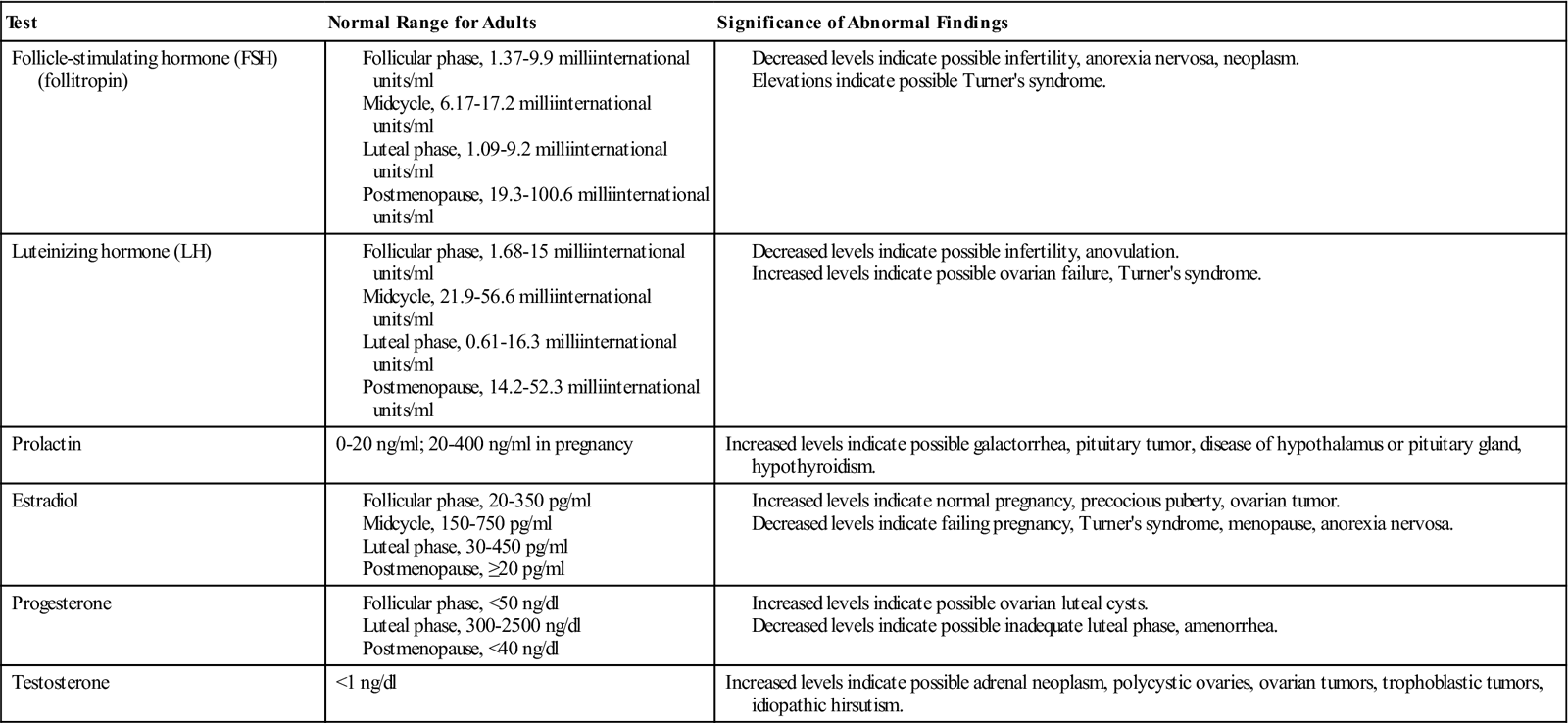

Surgical Technologist Considerations

As a part of the surgical team, the surgical technologist should check the chart and consult with the perioperative nurse and/or surgeon about the specifics of the procedure. For the surgical technologist to be adequately prepared for the procedure, the surgical technologist must have a clear understanding of the procedure and why the procedure is necessary (e.g., disorder, disease, infection). Ensuring patient safety is the number one goal of the surgical technologist. Understanding the dynamics of the procedure and the patient will prevent mistakes in the operating room. In addition to the patient allergies, it is necessary to be aware of the patient’s medical history as noted by the perioperative nurse and surgeon. The medical history includes a chronological listing of each pregnancy with length of gestation, type of delivery, complications during pregnancy, duration of labor, and fetal weight. In addition to the medical history, the assessment also taken by the perioperative nurse and surgeon will add valid insight. This may include the patient’s social history, sexual history, and any relevant cultural and/or religious preferences. Reviewing laboratory findings and other test results may also reveal vital information pertinent to the operative procedure preparation (Table 5-1).

TABLE 5-1

Common Laboratory Studies Used in the Reproductive Assessment

Modified from Lowdermilk DL: Assessment of the reproductive system. In Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML, editors: Medical-surgical nursing: patient-centered collaborative care, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.

Another important factor the surgical technologist should consider is the challenges of different approaches to OB/GYN procedures (sterile, clean, dirty, or a combination). As a rule, procedures utilizing an abdominal approach are sterile and those with a vaginal approach are clean/dirty. Please note: In procedures that utilize both abdominal and vaginal approaches (e.g., laparoscopic surgical interventions), the sterile field must be kept separate from the nonsterile field. Gloves should be changed when changing from the vaginal aspect of the procedure (clean) and moving to the abdominal aspect (sterile).

Also, the surgical technologist should consider the setup of tables for different OB/GYN interventions. Procedures using the vaginal approach (e.g., vaginal delivery, cerclage, and D&C) will not generally have a mayo stand. Back tables will be used and positioned at the patient’s feet. It is not uncommon for the physicians to stand on one side of the back table and the surgical technologist on the other.