Repair of Hernias

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter the reader will be able to:

• Identify the anatomy associated with hernia repairs

• Correlate physiology to conditions requiring surgical intervention

• Identify tissue layers involved in opening and closing sequences of hernia repair

• Compare diagnostic methods for determination of surgical interventions

• Identify specialized instrumentation, equipment, and supplies utilized in hernia surgery

• List the pharmacologic/hemostatic agents in hernia surgery

• Recognize the surgical technologist considerations when dealing with hernias

• Describe the procedures and approaches to hernia repairs

• Distinguish between the different types of inguinal and ventral hernia repairs

Overview

A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a peritoneum-lined sac through the musculoaponeurotic covering of the abdomen. The word hernia is a Latin term that means “rupture” of a portion of a structure. Descriptions of hernia reduction date back to Hammurabi of Babylon and the Egyptian papyrus (History box). Weakness of the abdominal wall, congenital or acquired, results in the inability to contain the visceral contents of the abdominal cavity within their normal confines. This defect occurs frequently; hernia repair is the most common operation in general surgery (Menon, 2008). More than 700,000 surgical procedures are performed each year to repair congenital hernia defects; nearly 75% of all acquired hernias occur in the inguinal region. Of these, about 50% of hernias are indirect inguinal hernias and 24% are direct inguinal hernias. Incisional and ventral hernias account for approximately 10% of all hernias; as the frequency and magnitude of abdominal surgeries have increased in recent years, so has the incidence of incisional hernia. Femoral hernias account for 3%, and unusual hernias account for the remaining 5% to 10%.

Hernias occur most often in males. The most common hernia in both males and females is the indirect inguinal hernia. Femoral hernias occur much more frequently in females, and only 2% of females will develop inguinal hernias in their lifetime. Also, hernias occur more commonly on the right side than on the left. Herniorrhaphy is one of the most common operative procedures performed and is the preferred treatment when a defect is detected.

Hernias have a tremendous economic significance in the United States. The number of workdays lost is substantial. The trend toward ambulatory surgery for hernia repair is one of many attempts to provide cost-effective healthcare that also leads to patient satisfaction.

A hernia can occur in several places in the abdominal wall, with protrusion of a portion of the parietal peritoneum and often a part of the intestine. The weak places or intervals in the abdominal aponeurosis are (1) the inguinal canals, (2) the femoral rings, and (3) the umbilicus. Any number of conditions causing increased pressure within the abdomen can contribute to the formation of a hernia. Contributing factors to hernia formation include age, gender, previous surgery, obesity, nutritional status, and pulmonary and cardiac disease. Loss of tissue turgor occurs with aging and in chronic debilitating diseases. Current evidence suggests that adult male inguinal hernias are likely associated with impaired collagen metabolism and weakening of the fibroconnective tissue of the groin (Gilbert et al, 2009). Smoking has also been noted as a contributing factor to hernia formation (Read, 2004). A successful herniorrhaphy is measured by the percentage of recurrence, the number of complications, the total costs, and the ability to return to normal activities of daily living (Research Highlight).

Surgical Anatomy

A hernia is a sac lined by peritoneum that protrudes through a defect in the layers of the abdominal wall. Generally, a hernia mass is composed of covering tissues, a peritoneal sac, and any contained viscera. Hernias may be acquired or congenital.

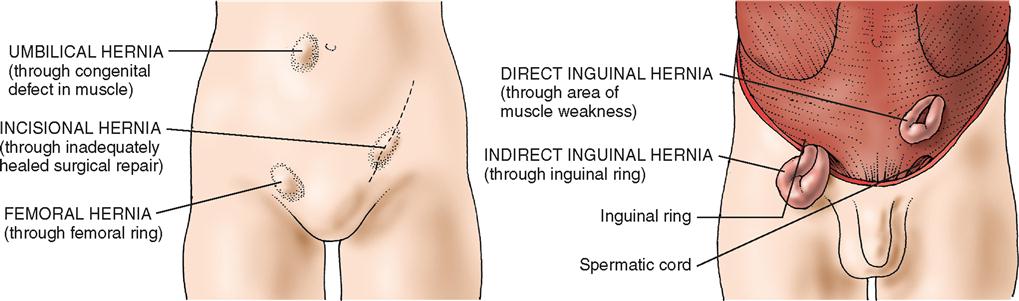

Depending on their location, hernias are classified as direct inguinal, indirect inguinal, femoral, umbilical, incisional, or epigastric (Figure 4-1). Hernias in any of these groups are either reducible or nonreducible; that is, the contents of the hernia sac either can be returned to the normal intraabdominal position or are trapped in the extraabdominal sac (incarcerated). The conditions preventing the return of the hernia contents to the abdomen can result from (1) adhesions between the contents of the sac and the inner lining of the sac, (2) adhesions among the contents of the sac, or (3) narrowing of the neck of the sac. Patients with incarcerated hernias may have signs of intestinal obstruction, such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and distention. The greatest danger of an incarcerated hernia is that it may become strangulated. In a strangulated hernia, the blood supply of the trapped sac contents becomes compromised and eventually the sac contents necrose. When bowel is strangulated in such a hernia, resection of necrotic bowel, in addition to the repair of the hernia defect, becomes necessary. This is a surgical emergency.

Inguinal Hernias

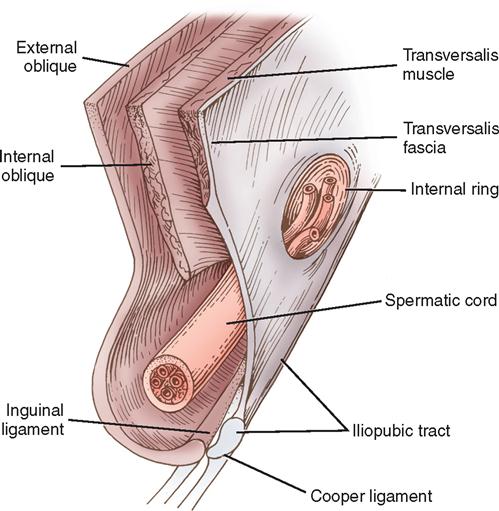

The anterolateral abdominal wall consists of an arrangement of muscles, fascial layers, and muscular aponeuroses lined interiorly by peritoneum and exteriorly by skin (Figure 4-2). The abdominal wall in the groin area is composed of two groups of these structures: a superficial group (Scarpa’s fascia, external and internal oblique muscles, and their aponeuroses) and a deep group (internal oblique muscle, transversalis fascia, and peritoneum).

Essential to an understanding of inguinal hernia repair is an appreciation of the central role of the transversalis fascia as the major supporting structure of the posterior inguinal floor. The inguinal canal, which contains the spermatic cord and associated structures in males and the round ligament in females, is approximately 4 cm long and takes an oblique course parallel to the groin crease. The inguinal canal is covered by the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle, which forms a roof (Figure 4-3). A thickened lower border of the external oblique aponeurosis forms the inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament, which runs from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. Structures that traverse the inguinal canal enter it from the abdomen by the internal ring, a natural opening in the transversalis fascia, and exit by the external ring, an opening in the external oblique aponeurosis, to go to either the testis or the labium. If the external oblique aponeurosis is opened and the cord or round ligament is mobilized, the floor of the inguinal canal is exposed. The posterior inguinal floor is the structure that becomes defective and is susceptible to indirect, direct, or femoral hernias.

The key component of the important posterior inguinal floor is the transversalis muscle of the abdomen and its associated aponeurosis and fascia. The posterior inguinal floor can be divided into two areas. The superior lateral area represents the internal ring, whereas the inferior medial area represents the attachment of the transversalis aponeurosis and fascia to the Cooper ligament (iliopectineal line). The Cooper ligament is the site of the insertion of the transversalis aponeurosis along the superior ramus from the symphysis pubis laterally to the femoral sheath. The inguinal portion of the transversalis fascia arises from the iliopsoas fascia and not from the inguinal ligament.

Medially and superiorly the transversalis muscle becomes aponeurotic and fuses with the aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle to form anterior and posterior rectus sheaths. As the symphysis pubis is approached, the contributions from the internal oblique muscle become fewer and fewer. At the pubic tubercle and behind the spermatic cord or round ligament, the internal oblique muscle makes no contribution and the posterior inguinal wall (floor of the inguinal canal) is composed solely of aponeurosis and fascia of the transversalis muscle.

None of the three groin hernias (direct and indirect inguinal hernias and femoral hernia) develops in the presence of a strong transversus abdominis layer and in the absence of persistent stress on the connective tissue layers. When a weakening or a tear in the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis and the transversalis fascia occurs, the potential for development of a direct inguinal hernia is established.

Femoral Hernias

When the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and its fascia are only narrowly attached to the Cooper ligament, a femoral hernia may develop. This results in an enlarged femoral ring and canal, which allows for the prominence of the iliofemoral vessels, resulting in femoral herniation (Lawrence, 2006).

The walls of the femoral sheath are formed anteriorly and medially from the transversalis fascia, posteriorly from the pectineus and psoas fascia, and laterally from the iliaca fascia. The pelvis ostium consists of a relatively fixed rim of bone and connective tissue: anteriorly and medially the iliopubic tract, posteriorly the superior ramus, and laterally the iliopectineal arch.

The femoral sheath is subdivided into three compartments. The lateral compartment contains the femoral artery, and the intermediate compartment contains the femoral vein. The medial compartment is the smallest and constitutes the femoral canal, which is formed anteriorly and medially by the iliopubic tract. This opening is bound laterally by the iliofemoral vessels and posteriorly by the superior pubic ramus and pectineus fascia. Superiorly, laterally, and inferiorly the fossa is formed by the falciform margin of the fascia lata.

Abdominal Hernias

The anterior abdominal wall is composed of external abdominal oblique muscles attached to a thick sheath of connective tissue called the rectus sheath. The linea alba extends superiorly and inferiorly from above the xiphoid process to the pubis. Beneath the rectus sheath lies the rectus abdominis muscles, laterally to the right and left of the linea alba. Lateral to the rectus abdominis is the linea semilunaris. The transversus abdominis muscles originate from the seventh to the twelfth costal cartilages, lumbar fascia, iliac crest, and the inguinal ligament, and insert on the xiphoid process, the linea alba, and the pubic tubercle. The third layer of abdominal wall includes the internal abdominal oblique muscles originating from the iliac crest, inguinal ligament, and lumbar fascia, and inserting on the tenth to twelfth ribs and rectus sheath.

Direct and Indirect Inguinal Hernias

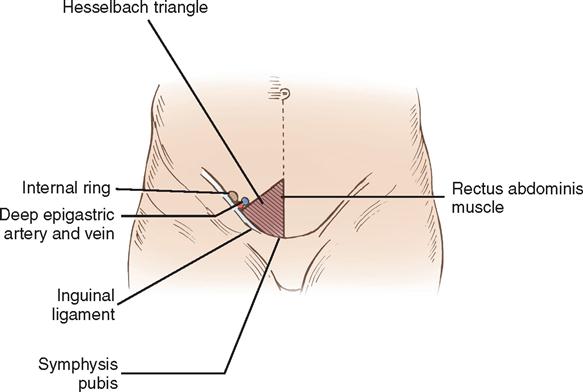

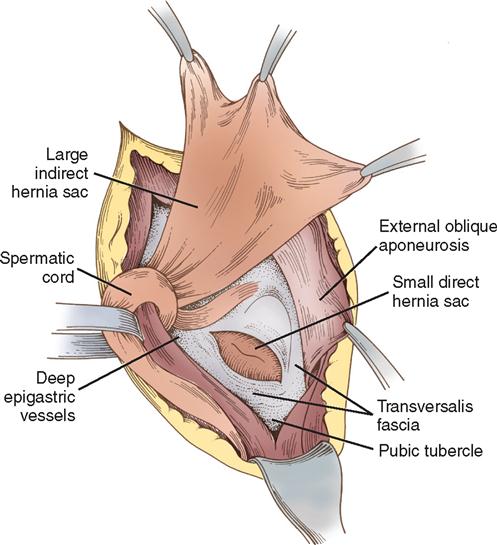

The deep epigastric vessels (inferior epigastric) arise from the external iliac vessels and enter the inguinal canal just proximal to the internal ring. The triangle formed by the deep epigastric vessels laterally, the inguinal ligament inferiorly, and the rectus abdominis muscles medially is referred to as the Hesselbach triangle (Figure 4-4). Hernias that occur within the Hesselbach triangle are called direct inguinal hernias. Indirect inguinal hernias occur laterally to the deep epigastric vessels. Both direct and indirect hernias represent attenuations or tears in the transversalis fascia (Figure 4-5).

Direct hernias protrude into the inguinal canal but not into the cord and therefore rarely into the scrotum. Direct inguinal hernias usually result from heavy lifting or other strenuous activities. Indirect hernias leave the abdominal cavity at the internal inguinal ring and pass with the cord structures down the inguinal canal. Consequently, the indirect hernia sac may be found in the scrotum. Indirect hernias may be either congenital, representing a persistence of the processus vaginalis, or acquired. In a congenital hernia, the hernia sac has a small neck, is thin-walled, and is closely bound to the cord structures. In an acquired indirect hernia, the neck is wide and the sac is both short and thick-walled. When both direct and indirect hernias are present, the defect is called a pantaloon hernia after the French word for “pants,” which this situation suggests.

Surgical Technologist Considerations

Assessment

Assessment of the patient should include the history of previous surgeries related to the herniated area as well as information relating to familial history. The patient’s nutritional status, the duration of symptoms, and a history of obesity, increased intraabdomnial pressure, chronic cough, constipation, benign prostatic hypertrophy, intestinal obstruction, colon malignancy, and, for women, pregnancy should all be taken into account. A list of the patient’s current medications should be collected, as well as a history of chronic illness and allergies, including latex allergies (because a Penrose drain may be used during the procedure). The patient’s occupation and physical activities should also be determined.

The diagnosis of hernias should be accompanied by clinical physical examination. Palpation of the herniated area reveals the contents of the hernia sac. Fingertip palpation allows the examiner to feel the edges of the external ring or abdominal wall. Having the patient stand and cough or prolonged strain during the examination also assists in the evaluation of the herniated area. If a definitive diagnosis is not confirmed, ultrasonic scanning and imaging techniques (e.g., computerized tomography [CT], herniography, standard radiography) may be employed.

In some patients, a hernia may cause no symptoms; its only sign may be a swelling or protrusion in a restricted area of the abdominal wall. If the hernia is unilateral, the patient notes the lack of a protrusion on the other side in comparison. The area may be visible when the patient stands or coughs and may disappear on reclining. Femoral hernias can be difficult to diagnose and may resemble an enlarged lymph node.

Preoperative testing includes a complete blood count. Patients older than 40 years may need an electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest radiograph. Patients with a history of more complex medical problems must be fully evaluated with appropriate laboratory tests. Preoperative assessment may also involve consultation with a pulmonologist or a cardiologist to ascertain whether surgical intervention is medically safe (this is referred to as clearance in patients with potential pulmonary or cardiac problems).

Planning

In planning for the surgeries on the hernia one must pay close attention to the operative approach and intended repair of the hernia, instrumentation, draping, and positioning of the patient depend on the type and approach—for example, open versus laparoscopic. With a laparoscopic approach, special video and recording equipment are needed. Also in most cases surgical mesh is used to repair the defect. The surgical technologist should be aware of the inventory levels of the styles and types of mesh and that there are enough resources available.

Instrumentation and Supplies

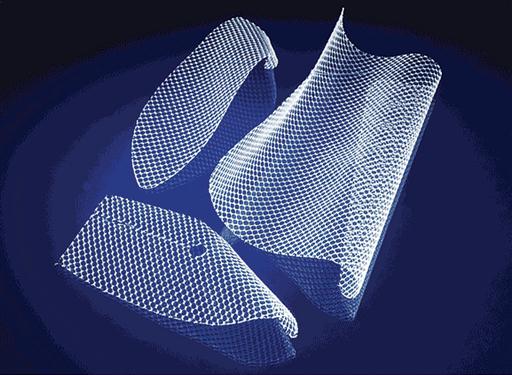

Instrumentation needed for an open hernia repair is a minor general surgery set. Depending on the location of the defect, a variety of supplies are needed. Mesh patches of synthetic material (Gore-Tex, Teflon, Dacron, Marlex, or Prolene) are now being widely used to repair hernias (hernioplasty). This is especially true for hernias that recur and for large hernias. Patches are sewn over the weakened area in the abdominal wall after the hernia is pushed back into place. The patch decreases the tension on the weakened abdominal wall, reducing the risk that a hernia will recur.

How Mesh Works.

There are many types of mesh products available, but surgeons typically use a sterile, woven material made from a synthetic plasticlike material, such as polypropylene. The mesh can be in the form of a patch that goes under or over the weakness, or it can be in the form of a plug that goes inside the hole. Mesh is very sturdy and strong, yet extremely thin. It is also soft and flexible, to allow it to easily conform to body’s movement, position, and size. Mesh is generally available in various measurements and can often be cut to size. Depending on the repair technique used, the mesh is placed either under or over the defect in the abdominal wall and held in place by a few sutures. Mesh acts as “scaffolding” for new growth of a patient’s own tissue, which eventually incorporates the mesh into the surrounding area. Figure 4-6 shows an example of mesh.

Surgical Setup: Open Hernia

The mayo setup for the open hernia is similar to a minor general surgery setup. A #10 blade or #15 blade on a #3 handle is the instrument used on the skin. Typically the #15 blade will be used on the fascia. An Army/Navy or a small Richardson retractor will be used to gain exposure to the surgical site. A Weitlaner self-retaining retractor may be used as well. Metzenbaum scissors will be the instrument of choice for the soft tissue dissection. Once the defect is exposed the surgeon will use at least four Criles or small Kelly hemostats to clamp the outer rim of the defect, allowing the contents of the hernia sac to be reduced into the abdomen or groin. A standard needle driver and straight mayo scissors complete the setup.

Surgical Setup: Laparoscopic Hernia

The mayo setup and instrumentation for the laparoscopic hernia repair mimics the setup for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A #15 blade on a #3 handle is the instrument used on the skin to prep for the trocars. Three trocars are used for access to the abdomen. The surgeon may use a 0-degree or 30-degree laparoscope. Laparoscopic scissors, dissector, and atramatic graspers are the instrumentation used to complete the procedure. The final piece to the laparoscopic repair of a hernia is the stapler/tacker used to secure the mesh to the abdominal wall.

Other Considerations

The patient undergoing hernia repair may receive a general anesthetic, an inguinal nerve block, a field block, a spinal or epidural block, a regional anesthetic with sedation, or a local anesthetic with sedation. Routine monitoring equipment, such as a three-lead or five-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), oxygen-saturation monitor, and blood pressure cuff, is used for a hernia repair. An intravenous (IV) line is inserted for fluid replacement and medication administration. The surgical site is marked as part of the preoperative verification process and rechecked during the time-out. In 2008 the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a surgical safety checklist as part of its “Safe Surgery Saves Lives” initiative. As part of the time-out, it recommends that all members of the surgical team identify themselves and their roles and ask simple questions such as, “Does everyone agree that this is Patient X, undergoing a right inguinal hernia repair?” The initiative also recommends an active role for the perioperative nursing team, who should review critical information such as confirming sterility of the instruments and supplies (including indicator results); discussing any equipment issues or concerns; noting whether antibiotic prophylaxis has been given within the last 60 minutes, if applicable; and verifying whether essential imaging is displayed, if applicable (WHO, 2008). Before the time-out, surgical team members may share any concerns about the planned procedure during a preoperative briefing (Research Highlight).

The patient is usually positioned supine with basic prepping and draping procedures followed. As with any surgical procedure, the prep solution must dry before the start of the surgical procedure as part of fire safety measures. To maintain the patient’s dignity and modesty, expose only the part of the patient’s body necessary for antimicrobial skin preparation (Beyea, 2007). Instruments used for herniorrhaphies are those found in standard laparotomy sets, laparoscopy sets, or minor sets.

A self-retaining retractor, such as a Weitlaner, facilitates the separation of tissue layers. A moistened Penrose drain is often used to retract the spermatic cord structures for better exposure. Because the peritoneal cavity may be entered in this procedure, sponge, sharp, and instrument counts are recommended.

With a sliding hernia or an incarcerated hernia, the possibility of having to enter the peritoneal cavity must be considered. If the hernia is strangulated, necrotic bowel must be resected and instruments for performing a bowel anastomosis must be available. For this procedure, antibiotics may be added to the irrigation to prevent an infection. Safe medication practices must be followed. All medications and solutions on and off the sterile field must be labeled. When the antibiotic solution is passed to the surgeon, the surgical technologist or other scrub person should announce the name and strength of the antibiotic solution to be used for irrigation.