PERTINENT HISTORY & PHYSICAL EXAM FOR GYNECOLOGIC DISEASES

Accurate diagnosis and treatment of gynecologic disease begins with obtaining a complete history and physical examination. A thorough history should include

First day of the most recent menstrual cycle

Current genital tract symptoms

Age at first menses (menarche)

Interval from starting one menses to the next (cycle length)

Duration and amount of menstrual flow

Presence or absence of irregular or unexplained bleeding

Symptoms associated with each menstrual cycle such as cramping before or during menses

Other genital tract symptoms such as urinary or fecal incontinence, prolapse, dyspareunia, discharge, or pruritus

Sexual history including assessment of risk factors such as knowledge of safe sex practices, age of first intercourse (coitarche), number and gender of partners, and presence of any history of abuse

Number of pregnancies and subsequent outcome including term delivery, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or abortion

Contraceptive use including type, duration

History of sexually transmitted disease such as infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), gonorrhea, or Chlamydia

Adequacy of cervical cancer screening with Pap tests including date of most recent screen and any prior history of abnormal screens

History of any gynecologic surgery including type, date, and indication

Age of menopause

Presence of postmenopausal bleeding regardless of amount of flow

Hormone therapy of any type including oral contraceptives, postmenopausal estrogen replacement therapy, hormone therapy of breast cancer, etc

Family history of pertinent cancer sites including ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer. Determine the age at time of cancer diagnosis and relationship of the affected individual to the patient

Determine the ethnicity of the patient regarding potential for hereditary diseases

Perform a complete pelvic examination. Inspect external genitalia including vulva and urethra for development, symmetry, and visible lesions. Place a vaginal speculum to inspect the vagina and cervix for symmetry, or visible lesions and perform Pap test, cultures, or wet mount tests as indicated to evaluate symptoms or update screening. Bimanual examination is then performed with careful compression of pelvic viscera between the examiner’s hand on the abdominal wall and the finger(s) in the vagina. The process is repeated with the rectovaginal examination whereby one finger is placed in the vagina and one is inserted into the rectum. The rectovaginal exam allows the examiner to feel higher into the pelvis and may improve the ability to feel the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, cul de sac peritoneum, ovaries, rectocele, and sphincter integrity. The rectovaginal exam is particularly important for assessing pelvic masses or malignancies, rectocele, and fecal incontinence.

EMBRYOLOGY & ANATOMY

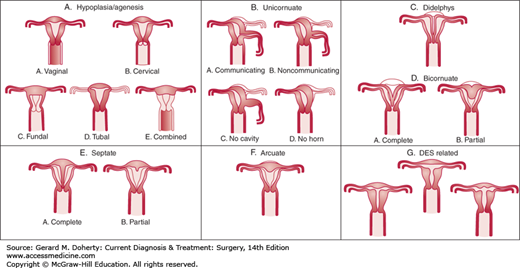

Development of the reproductive tract in the female fetus results from fusion and differentiation of the Müllerian ducts and the urogenital sinus. Fusion defects may result in duplication, malformation, or absence of genital tract structures. The most common defects are imperforate hymen, presence of longitudinal or transverse septae within the vagina, congenital absence of the vagina, and duplication defects of the uterus (Figure 39–1). The etiology of most of these congenital defects is idiopathic, but some cases arise as a result of teratogens such as androgen exposure to the developing fetus during the first and second trimesters.

Careful examination of the newborn is necessary. Cursory examination of the genital structure of the newborn may result in errors of gender assignment. Ultrasound and/or MRI, examination under anesthesia, and possible laparoscopy or hysteroscopy provide information for accurate diagnosis. One-third or more of children diagnosed with genital tract anomalies will have associated with anomalies of the urinary tract such as absent kidney, horseshoe kidney, and duplication of ureters.

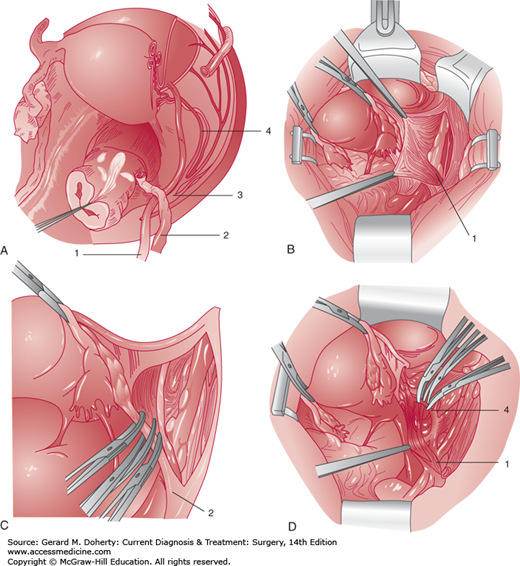

The pelvis is a space constrained by bony architecture and filled with gastrointestinal urologic and gynecologic viscera. The blood supply is rich, including the external and internal ileac arteries and veins, and numerous branches within the pelvis. Motor nerves including the sciatic, obturator, and femoral nerves transit the pelvis along the pelvic sidewall. Sensory nerves including the genitofemoral nerve are superficially located and easily injured. The ureter is closely placed to the uterine artery and is at risk for injury during hysterectomy procedures (Figures 39–2A and 39–2B). A pelvic surgeon must be intimately familiar with the close spacing of critical pelvic structures to minimize risk of injury.

Figure 39–2.

Pelvic retroperitoneal anatomy. A: Dissected right retroperitoneal space illustrating the course of the pelvic ureter. The right uterine adnexa are transected adjacent to the uterus, the ovarian vessels are severed just distal to the pelvic brim, and the peritoneum is removed from the right pelvic sidewall and the right portion of the bladder. The ureter (1) enters the pelvis by crossing over the bifurcation of the common iliac artery just medial to the ovarian vessels (2). It then descends medial to the branches of the internal iliac artery (3). The ureter then courses through the cardinal ligament and passes under the uterine artery (4, “water under the bridge”) approximately 1–2 cm lateral to the cervix at the level of the internal cervical os. The origin of the uterine artery from the internal iliac artery (3) is shown. The ureter then courses medially toward the base of the bladder. The distal part of the ureter is associated with the upper portion of the anterior vaginal wall. B: The retroperitoneal space is entered, and the peritoneum is retracted medially to show the ureter (1) crossing over the external and internal iliac artery bifurcation. Note that the ureter remains attached to the peritoneum of the pelvic sidewall and the medial leaf of the broad ligament. C: The ovarian vessels (2) are clamped and transected after visualization of the ureter. D: The uterine artery (4) is being clamped and transected. Note the ureter (1) crossing under this vessel lateral to the cervix.

THE LOWER GENITAL TRACT: VULVA, VAGINA, & CERVIX

As recently as 1945, cervical cancer and related lower genital tract cancers were the most common cancers in women. With the advent of the Pap test in the 1940s, cervical cancer incidence began to fall with more than an 80% reduction of risk of mortality in the ensuing six decades. It is now understood that virtually all cervical cancers and some vaginal and vulvar cancers are caused by persistent infection with oncogenic strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). There are more than 75 HPV types identified, with types 6 and 11 most commonly associated with condyloma and types 16 and 18 associated with preinvasive and invasive carcinoma. Prevalence of HPV infection is as high as 80% of the population, but most infections are transient in nature. With appropriate screening and treatment to detect individuals with persistent high-risk HPV infection, the risk of developing invasive cervical cancer is low. In parts of the world without screening, cervical cancer remains prevalent and is the second most common cancer diagnosis for unscreened women. FDA approval of vaccination effective for the prevention of oncogenic HPV strains occurred in 2006 and has the potential to greatly reduce HPV mediated lower genital tract cancers in women.

A number of professional groups, including the American Cancer Society, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Society for Clinical Pathology, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have issued consensus guidelines for cervical cancer screening that were updated in 2012. The US Preventive Services Task Force issued nearly identical recommendations in 2012. The guidelines address initiation of screening, screening interval, and discontinuation of screening.

When to initiate screening

Begin at age 21

When to discontinue screening

Age > 65 with adequate negative prior screening

Hysterectomy

Discontinuation of screening should not occur if the patient has a history of CIN2, CIN3, or adenocarcinoma in situ. In this case screening should continue for 20 years

Screening interval

Women aged 21-29 years

Cytology alone every 3 years

Liquid-based or glass-smear cytology is acceptable

Women aged 30-65 years

Cytology with high-risk HPV cotest every 5 years (preferred)

Cytology alone every 3 years (acceptable)

Women vaccinated against HPV

Follow age-specific guidelines

If cytology or HPV testing results are abnormal, then further evaluation is warranted. The ASCCP issued guidelines in 2013 that addressed triage and treatment for women with screening test abnormalities. Key points are as follows:

Cytologic tests should be reported using standard nomenclature defined by the Bethesda System. Key preinvasive diagnoses with which the clinician should be familiar include

Atypical squamous cells (ASC). The report will indicate either “uncertain significance” (ASC-US), or “cannot rule out high-grade dysplasia” (ASC-H). ASC-US should be further tested by ordering a reflex hybrid capture assay for high-risk HPV DNA unless the patient is an adolescent. ASC-H has a high risk of high-grade dysplasia and must be evaluated with colposcopy

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) is virtually always caused by HPV, and HPV testing has been shown not to be cost effective. In adolescent patients, a repeat cytology exam in 1 year is recommended. In adults, colposcopy is performed.

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) has a high likelihood of high-grade dysplasia on biopsy and invasive cancer will sometimes be detected. Patients with HSIL, regardless of age, are evaluated with colposcopy

Glandular abnormalities refer to disease in the endocervical canal. These lesions are difficult to see and may therefore be detected later. Skip lesions occur in 10%-15% of cases, indicating the importance of evaluating the entire canal with curettage or similar sampling methods. All three glandular lesions reported have a high likelihood of high-grade dysplasia and a moderate likelihood of associated invasive cancer. Colposcopy and endocervical gland sampling with curettage with possible endometrial sampling is required. Cells in this category will be reported as

Atypical glands, not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS)

Atypical glands, favor neoplasia

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)

Adolescents and young adult women, defined as being 24 years of age and younger, have a very high prevalence of HPV infection and a very low likelihood of cervical cancer. Because the disease will often regress in this age range, management guidelines have become progressively more conservative

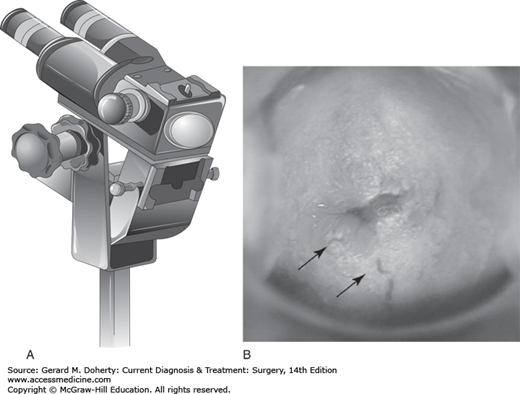

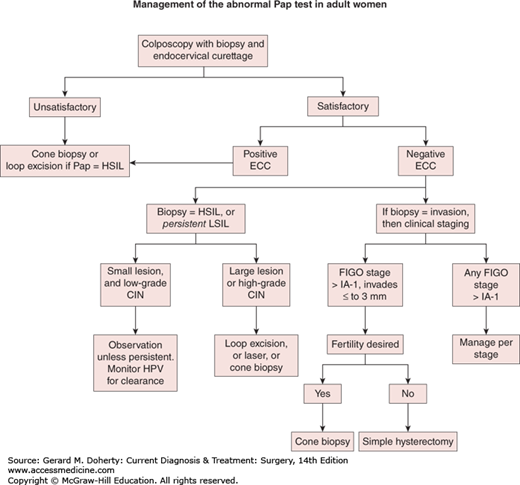

The colposcope is a binocular microscope (Figure 39–3) that allows close inspection of the squamo-columnar junction (SCJ) on the cervix where the majority of squamous cervical cancers arise. High-grade lesions have a characteristic appearance including white light reflection after staining with acetic acid in areas of dysplasia (aceto-white change), abnormal vascular patterns (punctation, mosaic, and atypical vessels), and altered contours. Small biopsies are obtained with colposcopic guidance using cervical biopsy forceps designed for this task. Treatment decisions are based on biopsy results. (Figure 39–4).

Biopsy proven low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN-1) has a high likelihood of spontaneous regression with a median time of 2 years and very little likelihood of progressing to cancer. Management is conservative in order to minimize treatment morbidity that has been shown to adversely affect fertility. Persistence of disease longer than 2 years may either be treated or surveillance may be continued

Biopsy-proven high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN 2-3) has a much higher risk of progressing to invasive disease if left untreated. Treatment options are discussed in the section on Surgery for Benign Cervical Disease

HPV mediated disease may also affect the vagina and vulva. Colposcopic examination and directed biopsies allow triage of lesions into low-grade and high-grade lesions that are managed either by surveillance or removal, respectively

A new consensus system of nomenclature for squamous neoplasia of the anogenital tract was published in 2012. In this system, neoplasms of the cervix, vagina, and vulva are now classified as low-grade or high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasms (LSIL and HSIL, respectively). This two-tiered classification system was designed to reflect the understanding of the biology of these lesions, and recognizes that LSIL rarely progresses, while HSIL has a significant risk of progression to cancer

Figure 39–4.

Colposcopy triage. Satisfactory colposcopy is defined as complete visualization of the squamocolumnar epithelium, which comprises the cervical region most likely to develop invasive disease. ECC refers to endocervical curettage to obtain tissue from the endocervix above the area that may be inspected with the colposcope. Colposcopically directed biopsies are taken. Low-grade dysplasia usually resolves and the preferred treatment is observation with periodic retesting for high-risk HPV DNA on 12-month intervals. Any high-grade CIN in women 25 years and older must be treated. Persistent low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) may be treated or surveillance may be continued. New guidelines treat adolescent and young adult patients differently. See text for details.

There are a large number of possible masses and benign neoplasms of the vulva. The clinical approach is to rule out potential malignancy and to treat symptomatic lesions. Biopsy or excision of small masses is usually performed in the office setting under a local anesthetic with either a punch biopsy instrument or scalpel. Punch biopsy sites are usually left open, while elliptical excisions are closed with fine, interrupted, absorbable sutures. The differential diagnosis for benign lesions is as follows:

Solid lesions

Leiomyoma

Natural History: Uncommon on vulva. Benign smooth muscle tumor that arises from deep connective tissues. Occurs at any age, predominating in fourth and fifth decades. May become very large. Rarely undergoes malignant degeneration

Appearance: Slowly growing, firm, usually mobile subcutaneous nodule

Diagnosis: Excisional biopsy

Treatment: Local complete excision

Lipoma

Natural History: Uncommon on vulva. Benign tumor of histologically normal appearing adipose cells. Large lesions may ulcerate. Usually asymptomatic. Rarely associated with family Lipoma syndrome, an autosomal dominant disease. Rarely undergoes malignant degeneration

Appearance: Soft, rounded, slowly growing sessile or pedunculated mass ranging widely in size

Diagnosis: Excisional biopsy if symptomatic

Treatment: Local excision if symptomatic

Syringoma

Natural History: Benign tumor of eccrine ductal origin within fibrous stroma. Occurs mostly after puberty

Appearance: Multiple, 1-2 mm, flesh-colored or yellow papules on lateral labia major

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local excision

Trichoepithelioma

Natural History: Rare benign tumor on vulva, derived from hair follicle without hair development

Appearance: Single or multiple small pink or flesh colored nodules that can mimic basal cell carcinoma

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local excision

Granular cell tumor

Natural History: Rare benign tumor of nerve sheath. Occurs in adults and children. Usually asymptomatic and solitary in 85%

Appearance: Slow growing subcutaneous nodule, usually on labia majora, clitoris, or mons pubis

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Wide local excision

Neurofibroma

Natural History: Rare on vulva. Benign tumor of nerve sheath. Half occur in patients with von Recklinghausen disease, an autosomal dominant heritable disease affecting skin, nervous system, bone, and endocrine glands. Rare before puberty. Rarely undergoes malignant degeneration

Appearance: Solid, cutaneous nodules usually less than 3 cm, but reported as large as 25 cm.

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance of von Recklinghausen disease or biopsy.

Treatment: In asymptomatic patients with von Recklinghausen disease, no treatment for a vulvar lesion is needed. For symptomatic patients, local excision

Schwannoma

Natural History: Rare. Benign tumor of neuroectodermal nerve sheath

Appearance: Usually solitary

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local excision

Glandular lesions

Papillary hidradenoma

Natural History: Benign tumor of apocrine sweat glands. Contains both glandular and myoepithelial elements. Occurs after puberty. Usually asymptomatic. Virtually always in Caucasian women

Appearance: Hemispherical in shape, measuring less than 2 cm in diameter. Usually located in labia majora or lateral labia minora

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local Excision

Nodular hidradenoma

Natural History: Benign tumor of eccrine sweat glands. Probably arises from embryonic rests. Clear cells on biopsy. Rare on vulva

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local Excision

Ectopic breast or nipple

Natural History: Rare. May occur on the vulva with or without underlying glands and lactation has been reported. Rarely undergoes malignant degeneration

Appearance: Amorphous swelling of the labia most often detected with pregnancy. Pigmented vestigial nipple may or may not be present

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local excision if symptomatic

Endometriosis

Natural History: Rare on vulva. Benign ectopic endometrial tissue. May cause cyclic pain and may ulcerate or bleed

Appearance: Nodule with blue or red-brown appearance. Cyclic tenderness

Diagnosis: Biopsy

Treatment: Local excision

Cysts

Bartholin cysts or masses

Natural History: Cysts are common, arising in 1%-2% of women. Cysts often occur after gland abscesses, although the duct may become occluded any time. Small cysts usually asymptomatic. Large or infected cysts are painful

Appearance: Spherical cyst or nodule in subcutaneous tissue of posterior labia majora

Diagnosis

Incise and drain abscesses

Biopsy recurrent cysts or solid nodules

Treatment

Incise and drain abscesses using a small balloon-tip catheter (Word) catheter introduced through a stab incision in the medial aspect of the cyst cephalad to the hymen. The catheter should remain in place for 2 weeks to allow tract epithelialization. In the event of surrounding cellulitis, antibiotic therapy can be added

Marsupialize or resect recurrent cysts

Resect solid nodules since these may be malignant

Epithelial inclusion cyst (sebaceous cyst)

Natural History: Common. Usually on labia majora. Can occur at any age and may be solitary or multiple. Usually asymptomatic. Caused by trauma to skin or occlusion of pilosebaceous duct

Appearance: Single or multiple, round cysts usually ranging from 2-3 mm up to 1-2 cm in diameter. Often have yellow color

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance

Treatment: No treatment if asymptomatic. If symptomatic, local excision

Wolffian cyst (Mesonephric cyst)

Natural History: Uncommon. Benign, thin-walled cysts on lateral vagina at the introitus

Appearance: Round cysts with thin smooth walls on lateral vagina at the introitus (Diagnosis: Clinical appearance or biopsy

Treatment: No treatment if asymptomatic. If symptomatic, local excision

Cyst of canal of Nuck (Mesothelial cyst)

Natural History: Uncommon. Benign cyst

Appearance: Smooth cysts usually located in anterior labia majora or inguinal canal. Thought to be due to peritoneal inclusions. May become large. Differential diagnosis includes inguinal hernia

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance or excisional biopsy

Treatment: No treatment if asymptomatic. If symptomatic, local excision

Vascular lesions

Angiokeratoma

Natural History: Very common. A clinically insignificant variant of hemangioma that occurs almost exclusively on vulva (and scrotum in men). Occurs during reproductive years. Contains dilated vessels and may have hyperkeratotic overlying epithelium. May resemble Kaposi sarcoma or angiosarcoma. Some forms associated with inborn errors of glycosphingolipid metabolism

Appearance: Red to purple to brown-black 2-5 mm papules usually in large numbers anywhere on the vulva

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance. Occurrence of multifocal lesions in childhood may indicate inborn errors of glycosphingolipid metabolism

Treatment: None, if asymptomatic. Symptomatic lesions treated with laser ablation, electrodessication, or local excision

Capillary hemangioma

Natural History: Capillary hemangioma (strawberry hemangioma) occurs in infants and young children. Usually regresses spontaneously over time. May ulcerate or bleed

Appearance: Well demarcated, red, slightly raised lesion

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance

Treatment: None if asymptomatic

Cavernous hemangioma

Natural History: Rare on vulva. Dilated vessels that may be associated with underlying pelvic hemangioma. Usually regresses spontaneously over time. May ulcerate or bleed

Appearance: Dilated vessels

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance

Treatment: None if asymptomatic

Nevi and pigmented skin lesions

Vitiligo

Natural History: Inherited disorder with loss of melanocytes. Asymptomatic

Appearance: Depigmented skin in well-circumscribed macular pattern

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance

Treatment: None

Fibroepithelial polyp (skin tag, acrochordon)

Natural History: Very common. Single or multiple. Hormonal factors are implicated in development and lesions are more common in obese or diabetic patients (Fisher, Nucci). Also common in axilla

Appearance: Multiple soft skin colored or pigmented lesions. Usually painless unless inflamed or torsed

Diagnosis: Gross recognition. Biopsy or excision if symptomatic

Treatment: Excise, electrodesiccate or freeze with liquid nitrogen if symptomatic

Seborrheic keratosis

Natural History: Common on body but uncommon on vulva. Usually occur after age 30. Probably autosomal dominant inheritance (Fitzpatrick). Multiple lesions occurring over a short period of time may indicate internal malignancy (Leser-Trelat syndrome)

Appearance: Lesions appear “stuck on” and are brown to black in color. Most are asymptomatic but can be pruritic. Occur on hair bearing skin

Diagnosis: Gross appearance, biopsy or excision

Treatment: If asymptomatic, no treatment. If symptomatic, excise, electrodesiccate, curette, or freeze with liquid nitrogen

Lentigo simplex

Natural History: Most common hyperpigmentation lesion on vulva. Occurs on skin and mucous membranes

Appearance: Usually small, less than 4 mm, flat, uniformly pigmented. Often resemble junctional nevi

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance. Biopsy only if clinical morphology worrisome. Remember ABCDE criteria: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegations, Diameter larger than 6 mm, Enlargement or Elevation

Treatment: None required

Vulvar melanosis

Natural History: Hyperpigmented macules or freckles are benign and asymptomatic. They are usually acquired, beginning between ages 30 and 40

Appearance: Asymptomatic brown to black irregular macular patches on vulva

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance. Biopsy only if clinical morphology worrisome. Remember ABCDE criteria: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegations, Diameter larger than 6 mm, Enlargement or Elevation

Treatment: None required

Acquired melanocytic nevocellular nevus

Natural History: Common, especially in Caucasians. Tend to develop in childhood and early adulthood, followed by gradual involution by age 60. Lesions are usually asymptomatic

Classification (Fisher)

Junctional nevus: melanocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction above the basement membrane. First stage of nevus evolution. Least common type on vulva

Compound nevus: melanocytes in both the dermis and above the basement membrane. Second stage of nevus evolution

Intradermal nevus: melanocytes exclusively in the dermis below the basement membrane. Final stage of evolution after which many nevi involute

Other types include halo nevus, blue nevus

Appearance:

Junctional nevus: Pigmented macule with smooth border and uniform tan, brown or dark brown pigmentation

Compound nevus: Papule with dome shape or macule. Dark brown or black color. May have hairs

Intradermal nevus: Papule with dome shape or macule. Skin colored, tan or light brown

Diagnosis: Clinical appearance. Biopsy if clinical morphology worrisome. Remember ABCDE criteria: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegations, Diameter larger than 6 mm, Enlargement or Elevation

Treatment: None required if asymptomatic and if ABCD criteria are benign. All others: local excision

Dysplastic nevus

Natural History:

Rare on the vulva

Lesions arise later in childhood than nevi in general and continue to develop throughout life

Sun exposure contributes to development of these lesions on other areas of the body. Several genetic loci have been implicated for development of melanoma

Risk of melanoma doubles with one dysplastic nevus and increases 12-fold if 10 or more dysplastic nevi are present

v. Dysplastic nevi are sometimes associated with a hereditary propensity for melanoma

Appearance

On biopsy, atypical cells are superficial and the deeper cells are without atypia. Pagetoid spread of cells is noted in lower third of epithelium

Tend to be larger in size than nevi (> 10 mm vs < 5 mm, respectively)

Dysplastic nevi are asymmetrical, with variegation of color

Diagnosis: Wood lamp accentuates pigmentation and margins are more easily delineated. Remember ABCDE criteria: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegations, Diameter larger than 6 mm, Enlargement or Elevation. Excisional biopsy

Treatment: Excisional biopsy. Careful longitudinal skin surveillance exams

Vulvar cancer accounts for about 5% of gynecologic malignancies. At least 90% of vulvar cancers are of squamous cell type. Etiology of vulvar carcinoma is grouped into the HPV-associated basaloid-warty histological group and the non-HPV-associated keratinizing squamous cancers. The age distribution is bimodal with younger women more likely to develop HPV-associated disease and older women more likely to develop keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. The latter group is often associated with lichen sclerosis of the vulva. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a preinvasive form of HPV-associated neoplasia and is often associated with persistent pruritus. Uncommon histological types of vulvar cancer include melanoma (6%), Bartholin gland adenocarcinoma (4%), basal cell carcinoma (< 2%), extramammary Paget disease of the vulva (< 1%), and rare sarcomas, found arising primarily in the soft tissues, or metastases from other tumor sites.

Lesions arise in the labia majora in about 50% of cases and about 25% of cases occur on the labia minora. Clitoral lesions and Bartholin gland adenocarcinomas are less common. The natural history of vulvar carcinoma includes spread to inguinal lymph nodes. Lesion depth and diameter are of prognostic value for assessing risk of metastasis, and to a lesser degree histological type, and presence of lymphatic involvement. Lesions of ≤ 1 mm depth have less than 1% risk of nodal metastasis, and define a category of microinvasive disease that may be treated more conservatively by omitting the inguinal node dissection. Lymph node status is the most significant predictor of survival.

In patients with HPV-mediated disease, multifocal involvement of the vagina and cervix predisposes to a significantly higher risk of cancer at these sites. Smoking is a cofactor for the development of HPV-mediated disease. Smoking cessation may reduce risk of persistent or progressive disease. Women with extramammary Paget disease, in in situ apocrine adenocarcinoma related to breast tissue developed along the milk-line in utero, there is a significant risk of a second, underlying adenocarcinoma elsewhere. Sites that require evaluation include colon, especially for perianal lesions, Bartholin gland, cervix, endometrium, ovary, and breast.

Cancer of the vulva is staged by International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria, which is a surgical staging system. Melanoma is staged using AJCC staging rules.

VIN occurs in women 15-20 years before the average age of invasive disease. Incidence has risen strongly and the average age at time of incidence has fallen from 52.7 years in 1961 to 35 years in 1992. One-third of lesions are solitary, and two-thirds are multifocal. Lesions are widely variable in size and may be slightly raised or papillary. Color variation ranges from white, red, or brownish patches on the skin or mucosa. Ulcerated lesions or underlying subcutaneous induration may indicate invasion. Larger lesions have a higher probability of lymph node involvement, but metastatic disease in the lymph nodes may not be palpable. Local spread may involve the urethra, vagina, anus, and rarely the symphysis pubis or other pelvic bones.

Biopsies are necessary to establish the correct diagnosis. The differential diagnosis is large and includes benign lesions discussed earlier in addition infections that mimic neoplasms and also vulvar dystrophies. Granulomatous infections such as lymphogranuloma venereum and granuloma inguinale of the vulva may be clinically suspicious, and biopsy of the involved may need to be supplemented with cultures for documentation of infection. These infections are rare unless a patient has traveled internationally. VIN is best diagnosed by colposcopic examination techniques including use if magnification and staining the epithelium with 5% acetic acid. Lesions usually appear acetowhite.

Focal VIN may be treated by wide excision or CO2 laser photoablation. Excision is preferred for lesions in the hair bearing skin and laser is generally less prone to cause scarring in the mucosal surfaces. Laser ablation is contraindicated if there is any suspicion of invasion. A skinning vulvectomy with split-thickness skin grafting is effective for widely multifocal disease. Extramammary Paget disease requires wide but superficial excision as the tumor cells often spread far wider than is visible to the surgeon. Local recurrences are common, but invasion is rare.

Vulvar cancer is staged using the international system developed by the FIGO (Table 39–1). Microinvasive lesions of less than or equal to1 mm invasion are adequately treated by wide and deep local excision with 1 cm margins due to the low likelihood of nodal spread. Stage I lesions are generally treated with radical local excision with a 1-2 cm margin. For lesions greater than 1 mm in depth, sentinel node mapping of inguinal nodes is carried out to assess for spread of disease. Radiation therapy with concurrent chemosensitization is required for inoperable lesions and for patients with positive nodes or involved resection margins.

| Stage | Revised 2009 |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor confined to vulva |

| IA | Lesion ≤ 2 cm in size, and stromal invasion of ≤ 1 mm, nodes negative |

| IB | Lesion > 2 cm in size, or stromal invasion of > 1 mm, nodes negative |

| II | Tumor of any size extending to adjacent perineal structures: (anus, lower 1/3 of urethra, lower 1/3 of vagina); nodes negative |

| III | Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures: (anus, lower 1/3 of urethra, lower 1/3 of vagina); inguinofemoral nodes positive |

| IIIA(i) | With 1 lymph node metastasis of ≥ 5 mm |

| IIIA(ii) | 1-2 lymph node metastases of < 5 mm |

| IIIB(i) | With 2 or more lymph node metastases of ≥ 5 mm |

| IIIB(ii) | 3 or more lymph node metastases of < 5 mm |

| IIIC | Positive nodes with extracapsular spread |

| IVA(i) | Invades upper urethra or vagina; bladder or rectal mucosa; or fixed to pelvic bone |

| IVA(ii) | Fixed or ulcerated inguinofemoral nodes |

| IVB | Any distant mets including pelvic nodes |

Following radical resection with negative nodes and margins, a 5-year rate of 90% is anticipated. If nodes are involved, survival is linked to number of nodes involved, unilaterality versus bilaterality, and bulk of disease.

Diagnosis of imperforate hymen is often delayed until puberty, when either a workup for primary amenorrhea has ensued or the patient presents with menstrual symptoms such as cramping, without associated menses. If the patient has obstructed flow of her menses, defined as hematocolpos, examination will reveal a bulging imperforate hymen. Confirmatory rectal exam will detect a bulging, cystic mass. In younger girls, the finding is more subtle due to the absence of swelling. Delay of diagnosis may result backpressure causing a cystically enlarged uterus (hematometra) and possible retrograde menstruation leading to endometriosis. In the presence of a tightly distended hematocolpos, compression of the bladder and ureters may result in urinary obstruction.

Imperforate hymen is treated with a hymenotomy, where the obstructed hymen is incised or resected with either a scalpel or laser.

Duplication of the vagina resulting in a septum may occur with or without similar defects in the uterus based on where the defect of Müllerian duct fusion occurred. The duplication may take the form of a partial longitudinal septum or complete duplication of the vagina. Patients will occasionally report bleeding despite placing a tampon during menses, indicating the possibility of a second passage for menstrual flow. Excision is performed transvaginally for symptomatic patients including those with dyspareunia, obstruction of labor or similar problems.

Occasionally, the vagina fails to communicate with the urogenital sinus at the introitus. This may result in formation of a transverse septum, most of which are partial. If the septum is imperforate, hematocolpos will develop following menarche. Marsupialization or excision of the septum restores vaginal patency.

Vaginal agenesis, or absence of the vagina, is associated with absence of the uterus in most cases. The lower vagina, derived from the urogenital sinus may be present, but Müllerian ductal structures comprising the upper two-thirds of the vagina and the uterus are absent or deficient. Diagnosis is usually made at time of evaluation for primary amenorrhea.

Vaginal agenesis is treated by reconstruction of a functional vagina. Treatment is usually deferred until the patient wishes to become sexually active. In a motivated patient, the vagina may be created by nonoperative dilation and elongation of the vulvar vestibule or vaginal introitus. This method, called the Frank nonoperative technique, requires up to 2 hours of dilating per day for 4-6 months. Success has been reported with vaginal dilators, vaginal molds, modified bicycle seat, and with intercourse alone. If there is failure to progress, or if the anatomy does not favor dilation alone, surgical construction using a skin graft (McIndoe procedure), interposed bowel, or myocutaneous flaps from the perineum are effective.

Gartner duct cysts are derived from mesonephric (Wolffian) duct remnants and contain a serous fluid. They are usually located in the lateral walls of the upper vagina and are generally asymptomatic. These cysts are detected most often during a routine physical examination. Small asymptomatic cysts require no treatment. Gartner duct cysts may occasionally reach 5-6 cm diameter. Larger or symptomatic cysts should be excised.

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is the term used to describe the preinvasive neoplastic changes that arise in the vagina. VAIN is frequently present whenever carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma of the cervix or vulva is present, and it may develop in the vagina years after completion of treatment for cancers of these two sites. Carcinoma in situ, or VAIN 3, of the vagina is most often detected with a Pap test. Subsequent evaluation with colposcopy, staining with 5% acetic acid and directed biopsies provide an accurate assessment of grade and location of disease.

Low-grade dysplasia (VAIN 1) has a low probability of progression and may be managed with surveillance using the same principles as for management of low-grade cervical dysplasia. High-grade dysplasia (VAIN 2-3) should be treated by local excision of involved areas or with CO2 laser photoablation. New terminology for these lesions was published in 2012. Low-grade lesions are now referred to as LSIL and high-grade lesions previously called VAIN 2, VAIN 3 and carcinoma in situ, are now referred to as HSIL. The irregular surface topography of the vagina caused by rugae makes successful visualization of lesions for treatment challenging. Recurrence rates for dysplasia are higher for vaginal dysplasia than for similarly treated cervical dysplasia, with a failure rate in the 25% range. Intravaginal placement of topical 5-fluorouracil is an off-label indication that has been reported in the literature, and failure rates are higher than for resection or ablation. Topical 5-fluorouracil has been reported to cause painful vaginal ulcers that heal poorly, limiting the utility of this treatment to carefully selected patients. Extensive involvement of the vagina may require subtotal or complete vaginectomy with skin grafting for maintenance of sexual function. For the elderly, sexually inactive patient, colpocleisis, where the vagina is resected and closed permanently is an option.

Invasive carcinoma of the vagina is rare, accounting for less than 2% of gynecologic malignancies. Most vaginal cancers involve extension from either cervical or vulvar cancers, both of which are more common than lesions arising in the vagina. By convention, if the cancer involves cervix or vulva in addition to the vagina, the tumor is categorized as either cervical or vulvar cancer, respectively. True vaginal cancer arises only in the vagina. About 85% of vaginal cancers are of squamous type. The next most common type is adenocarcinoma, usually with clear cell type. Rare primary tumors of the vagina include mixed mesodermal tumors, sarcoma botryoides (embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma), sarcoma, adenocarcinoma arising from Gartner duct or Müllerian duct remnants, embryonal carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.

The most common presenting symptoms of vaginal cancer include postmenopausal bleeding in about 65% of patients and persistent vaginal discharge in about 30%. Most tumors arise in the upper third of the vagina along the anterior and posterior surfaces. These sites are usually covered by the vaginal speculum and can easily be missed unless the physician observes all vaginal surfaces upon insertions and withdrawal of the speculum. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Staging of carcinoma of the vagina is defined by FIGO and is clinical rather than surgical (Table 39–2). Squamous cancers are most commonly found in postmenopausal patients, although they may occur even in adolescent patients. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina is more likely to occur in women below the age of 25, generally arising in vaginal adenosis. Diethylstilbestrol (DES) has been implicated in increasing the incidence of clear cell carcinoma from 1:50,000 in the unexposed population to 1:1000 in women exposed to DES in utero. Although DES is no longer produced or prescribed in this country, DES and similar substances have been detected in the environment and in some food supplies.

| FIGO Stage | Description | TNM Class |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ; intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 | Tis N0 M0 |

| Stage I | The carcinoma is limited to the vaginal wall | T1 N0 M0 |

| Stage II | The carcinoma has involved the subvaginal tissue but has not extended to the pelvic wall | T2 N0 M0 |

| Stage III | The carcinoma has extended to the pelvic wall | T1 N1 M0 T2 N1 M0 T3 N0 M0 T3 N1 M0 |

| Stage IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. Bullous edema as such does not permit a case to be allotted to stage IV | |

| IVA | Tumor invades bladder and/or rectal mucosa and/or direct extension beyond the true pelvis | T4 any N M0 |

| IVB | Spread to distant organs | Any T Any N M1 |

Treatment of vaginal cancer is most often a combination of radiation therapy and chemosensitization using treatment plans similar to cervical cancer. Radical surgery such as radical hysterectomy with vaginectomy is possible for selected, small, upper vaginal lesions, favoring lesions on the posterior wall due to the improved likelihood of attaining adequate margins. Surgery is preferred for young patients with clear cell carcinoma as long as negative margins can be attained. In over 50% of patients tumor has penetrated the vaginal wall at the time of the initial examination. Involvement of the bladder and rectum is common. Survival for stage I disease is about 70%, but falls to about 40% for stage II and stage III disease.

Cervical cancer is the twelfth most common cancer of women in the United States, but remains the second most common cancer of women worldwide. Almost all cervical cancers arise because of persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, most commonly types 16 and 18. Low-risk HPV types such as types 6 and 11 are usually associated with condyloma and rarely, if ever, are associated with cancer. Cervical cancer can be considered a sexually transmitted disease since most HPV infections are transmitted via sexual contact. Early sexual debut and multiple partners greatly increase the risk of exposure to high-risk HPV types. HPV infections are common and about 80% of the population will have detectable HPV antibodies indicating prior infection. In most infected individuals, the immune system will mount a successful response, with a median time to regression of infection of about 2 years. Persistent infection with a high-risk HPV type after age 30 increases the relative risk of cervical cancer more than 400-fold for HPV 16 over the population at large. Persistent infections and progression to cancer may be more likely in women who smoke or those with dietary deficiency of folate, and beta-carotene. Progression to cancer is usually gradual, allowing development of effective screening strategies with Pap tests and testing for high-risk HPV DNA in addition to effective triage with colposcopy. Low-grade lesions usually regress, making potentially destructive treatments that have an adverse effect on fertility unnecessary. In 2006, the FDA first approved a vaccine for primary prevention of HPV infection. The vaccine is targeted for adolescents prior to their sexual debut. Widespread vaccination may largely eradicate cervical cancer in the future, although the vaccines are selective only for the most common of high-risk HPV types raising the possibility of shifting prevalence of HPV types.

About 75% of cervical cancers are squamous type; the remainder consist of adenocarcinomas, mixed carcinomas (adenosquamous), and rare sarcomas (mixed mesodermal tumors, lymphosarcomas). The relative prevalence of cervical adenocarcinoma has risen in recent years and now accounts for about 25% of cases.

Most cervical cancers arise from a preinvasive dysplastic lesion through a process that generally lasts for years. Carcinoma in situ occurs most frequently in the fourth decade, whereas invasive carcinoma is encountered most often in perimenopausal women between ages 40 and 50. Once invasion occurs, spread is by direct extension to the vagina and the parametrium in addition to lymphatic channels to the iliac and obturator nodes, with occasional direct spread to para-aortic nodes. Staging is clinical, since not all stages will require surgery. The staging system defined by FIGO is used internationally, and is included in Table 39–3. Probability of lymph node metastasis increases according to the extent of the primary lesion, being approximately 12% in stage I, 30% in stage II, and 45% in stage III. About 80% of patients with stage IV cancer have lymph node involvement.

| FIGO Stage | Revised 2009 |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Carcinoma confined to cervix (extension to corpus would be disregarded) |

| IA | Invasive carcinoma, diagnosed only by microscopy. All macroscopically visible lesions, even with superficial invasion, are Stage IB |

| IA-1 | Measured stromal invasion ≤ 3 mm and ≤ 7 mm in horizontal spread |

| IA-2 | Measured stromal invasion > 3 mm and ≤ 5 mm with a horizontal spread of 7 mm or less |

| IB | Clearly visible lesion confined to the cervix or microscopic lesion greater than Stage IA |

| IB-1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤ 4 cm in greatest dimension |

| IB-2 | Clinically visible lesion > 4 cm in greatest dimension |

| Stage II | Tumor invades beyond uterus but not to pelvic wall or to the lower third of vagina |

| IIA | Tumor without parametrial invasion |

| IIA-1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤ 4 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIA-2 | Clinically visible lesion > 4 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIB | Tumor with obvious parametrial invasion |

| Stage III | Tumor extends to the pelvic wall and/or involves lower third of vagina and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney. Determination is based on rectal exam with no cancer-free space between tumor and pelvic wall |

| IIIA | Tumor involves lower third of the vagina, with no extension to pelvic wall |

| IIIB | Extends to pelvic wall or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| Stage IV | Carcinoma extends beyond true pelvis or with biopsy proven spread to bladder or rectal mucosa. Bullous edema does not cause case to be allotted to Stage IV |

| IVA | Spread to adjacent organs |

| IVB | Spread to distant organs |

Successful screening has greatly reduced the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer and its precursors over the last 50 years. Current screening recommendations for lower genital tract cancers of the vulva, vagina, and cervix have been discussed previously in this chapter. When a neoplastic lesion is detected by screening, proper and timely triage is needed. High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions are typically asymptomatic.

Colposcopic examination of the cervix is the gold standard for assessing dysplasia, carcinoma in situ and early invasive disease. Application of Lugol iodine can be a useful adjunct to the colposcopic exam. Normal mature squamous epithelium of the cervix and vagina contains glycogen and stains a dark brown color, whereas dysplastic cells lack glycogen and stain a light yellow color.

Colposcopically directed biopsy is performed for visible abnormalities including acetowhite change, abnormal vessels, ulceration, and papillary lesions. Biopsy confirmed CIN-1 is managed conservatively since most of these lesions regress spontaneously and there is very little risk of progression to cancer. Biopsy showing a high-grade dysplastic lesion including moderate dysplasia (CIN-2), severe dysplasia (CIN-3), and carcinoma in situ (CIN-3), are treated with either ablative therapy or resection using cryotherapy or electrosurgical loop excision, respectively. Treatment is directed to either ablation or removal of the entire transformation zone, defined as the area bounded by the original and current squamocolumnar junction. These two treatment modalities are usually performed in the office setting and are well tolerated. There are some exceptions when treating adolescent and young adult patients under age 25, so the clinician must be familiar with current guidelines. Some dysplastic lesions may extend into the endocervical canal including squamous lesions and most glandular lesions. The preferred treatment for lesions extending out of colposcopic view into the endocervical canal is usually excision with a cold-knife cone biopsy in the operating room. Both electrosurgical loop excision and cold-knife cone biopsy increase future risk of preterm delivery, mandating careful triage of only those individuals truly requiring an excisional therapy.

Early stromal defined as microinvasion, is usually asymptomatic. Larger lesions frequently cause postmenopausal bleeding (46%), intermenstrual bleeding (20%), or postcoital bleeding (10%). A watery or malodorous vaginal discharge may be the only symptom. Pain is a manifestation of advanced stage disease typically extending to the pelvic sidewall with entrapment of the sciatic nerve or femoral nerve. Inspection of the cervix typically reveals an ulcerated or papillary lesion of the cervix that bleeds on contact. The cytologic examination almost always demonstrates exfoliated malignant cells, although the false-negative rate for Pap tests approach 50% for invasive lesions due to obscuration of malignant cells by inflammation and necrotic debris.

Chronic cervicitis may appear similar to cancer of the cervix. Polyps of the cervix are often benign, but malignancy can only be ruled out with biopsy. Nabothian cysts are benign, common, and can appear bizarre to the untrained eye, but are readily distinguished from cancer by biopsy.

Spread of cervical cancer into the parametrium may cause obstruction of the ureter, resulting in hydroureter, hydronephrosis, and uremia. Bilateral obstruction of the ureters leads to failure of kidney function and death. Involvement of the iliac and obturator lymph nodes may lead to lymphatic obstruction resulting in lymphedema. Pelvic sidewall nerves, especially the sciatic nerve, may become compressed, causing sciatica or pain in the low back, hip, and leg. Tumor invasion into the bladder or rectum sometime causes vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula, especially following radiation therapy. Widespread metastases to lung, liver, brain, and bone may occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree