ANORECTAL ANATOMY

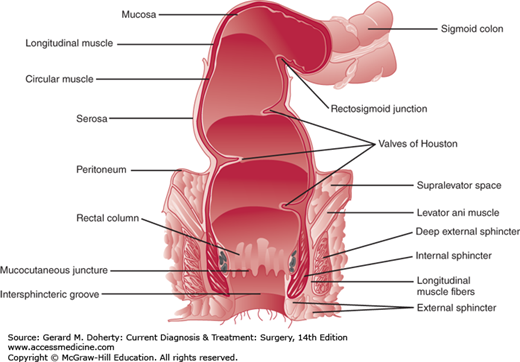

The anatomy of the anus and rectum dictates the clinical evaluation and treatment of patients with anorectal disorders (Figure 31–1).

From external to internal, the surface anatomy of the anorectum is comprised of gluteal skin, anoderm, the anal transitional zone, and proximally the rectal mucosa. The gluteal skin includes hair, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands. This area, particularly 3-5 cm of anal margin skin circumferentially around the anus, can commonly become infected with the human papilloma virus resulting in anal condyloma. Anal condyloma can also affect more proximal tissue in the anoderm and lower rectal mucosa. Perianal hidradenitis is also relatively common and develops in the apocrine sweat glands of the perianal skin. Unlike anal condyloma, perianal hidradenitis can only occur in the gluteal skin as there are no sweat glands in the anoderm.

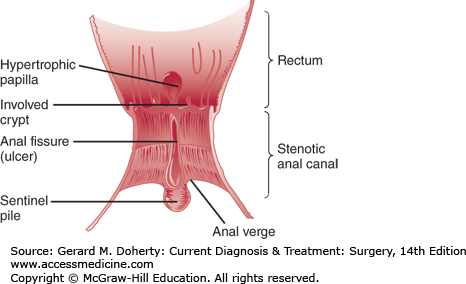

The anoderm begins at the anal verge and ends at the dentate line. Unlike the gluteal skin, the anoderm is devoid of hair and sweat glands. Anal fissures occur in the anoderm and can be associated with a sentinel tag externally and a hypertrophied anal papilla internally (Figure 31–2). Surgical excision of too much anoderm during hemorrhoidectomy or other anorectal surgery can result in anal stenosis.

The anal transitional zone lies between the squamous anoderm and the rectal mucosa. In this zone, squamous, cuboidal, transitional, and columnar epithelium exist with longitudinal ridges called the columns of Morgagni. Between the columns of Morgagni are anal crypts with associated anal glands that open into their bases. Clinically, the anal transitional zone is important for two main reasons. First, the anal transitional zone is the crossover from somatic to visceral innervation and for lymphatic drainage from the inguinal to the pelvic nodes. Lymphatics from the anal canal above the dentate line drain via the superior rectal lymphatics to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes and laterally to the internal iliac nodes. Below the dentate line, drainage occurs to the inguinal lymph nodes but can occur to the inferior or superior rectal lymph nodes. Second, the anal glands in the crypts are the site of anorectal abscesses and anal fistulas. Anatomically the anal glands in the crypts extend to a variable depth resulting in perianal, intersphincteric, or ischiorectal abscesses when these glands become blocked.

Proximal to the anal transitional zone is the rectal mucosa. Above the dentate line and underlying the rectal mucosa are the vessels that, when abnormally engorged, manifest as internal hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoids are not veins but arteriovenous connections that have pulsatile flow. Patients with bleeding from hemorrhoids can have significant blood loss. Further, internal hemorrhoids are covered by mucosa and because they are above the dentate line, they are viscerally innervated. This is the reason rubber-band ligation of internal hemorrhoids is possible without anesthesia. In contrast, external hemorrhoids are below the dentate line, covered by anoderm and skin. Any surgical intervention on external hemorrhoids requires some type of anesthesia.

Hemorrhoidal vessels are anchored by Treitz’ muscle. When the Treitz’ muscle attachments weaken, internal and external hemorrhoids can prolapse, bleed and cause perianal irritation and discomfort. Internal hemorrhoids can prolapse and can be confused with rectal prolapse. Generally, internal hemorrhoids prolapse in columns occurring in the right anterior, right posterior and left lateral quadrants around the anus. When the anus is examined, these prolapsing columns of internal hemorrhoids appear as radial folds. This is distinguished from the circumferential folds of rectal prolapse.

The rectum extends 12-15 cm proximal to the dentate line. The rectum has three curves that create folds called the valves of Houston. It is supported by the puborectalis and levator muscles that are also called the pelvic floor. In addition, the rectum is fixed posteriorly by presacral (Waldeyer) fascia, laterally by the lateral ligaments, and anteriorly by Denonvilliers fascia. The arterial supply of the anorectum is via the superior, middle and inferior rectal arteries. The superior rectal artery is the terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery and descends in the mesorectum. It supplies the upper and middle rectum. The middle rectal arteries arise from the internal iliac arteries and enter the rectum anterolaterally at the level of the pelvic floor musculature. They supply the lower two-thirds of the rectum. Collaterals exist between the middle and superior rectal arteries. The inferior rectal arteries—branches of the internal pudendal arteries—enter posterolaterally, do not anastomose with the blood supply to the middle rectum, and supply the anal sphincters and epithelium.

The venous drainage of the anorectum is via the superior, middle, and inferior rectal veins draining into the portal and systemic systems. The superior rectal veins drain the upper and middle thirds of the rectum and empty into the portal system via the inferior mesenteric vein. The middle rectal veins drain the lower rectum and the upper anal canal into the systemic system via the internal iliac veins. The inferior rectal veins drain the lower anal canal, communicating with the pudendal veins, and draining into the internal iliac veins. Communication between the venous systems allows low rectal cancers to spread via the portal and systemic systems. Lymphatic drainage of the upper and middle rectum is into the inferior mesenteric nodes. Lymph from the lower rectum may drain into the inferior mesenteric system or into lymphatics around the lower rectum that drain into the inguinal nodes and then into periaortic nodes. Below the dentate line, lymphatic drainage occurs primarily to the inguinal nodes but may drain into the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes.

The innervation of the rectum is from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nerves originate from the lumbar segments L1-3, form the inferior mesenteric plexus, travel through the superior hypogastric plexus, and descend as the hypogastric nerves to the pelvic plexus. The parasympathetic nerves arise from the second, third, and fourth sacral roots and join the hypogastric nerves anterior and lateral to the rectum to form the pelvic plexus. Sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers pass from the pelvic plexus to the rectum and internal anal sphincter (IAS) as well as other pelvic viscera. Injury to these nerves can lead to sexual and bladder dysfunction, and loss of normal defecatory mechanisms.

Beneath the surface anatomy of the anus and rectum are the anal sphincter muscles. The IAS muscle is involuntary and is responsible for anal canal resting tone. The IAS is innervated with sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Both are inhibitory and keep the sphincter in a basal state of contraction. The external anal sphincter (EAS) muscle is voluntary and responsible for anal canal squeezing tone. The external sphincters are skeletal muscles innervated by the pudendal nerve with fibers that originate from S2-4. The EAS muscle fuses with the pelvic floor muscles to create a bowl-like muscular support of the lower rectum.

While systemic diseases such as diabetes, scleroderma and multiple sclerosis can affect the anal sphincter muscles, far more common is direct injury to the sphincter muscles from vaginal delivery or surgery. Using transanal ultrasound to evaluate the anal sphincter muscles before and after vaginal delivery it has been demonstrated that approximately one-third of women injure their anal sphincter at the time of delivery. Fortunately, only one-third of these women develop fecal incontinence.

Operative intervention for hemorrhoids, anal fissure, and anal fistula can result in anal sphincter injury. Sphincter injury should not occur during hemorrhoid surgery as hemorrhoidal vessels are superficial to the anal sphincter muscles. Division of the anal sphincter is necessary and curative for anal fissure and for anal fistula treated by fistulotomy. While lateral internal sphincterotomy for anal fissure carries a fecal incontinence rate of less than 0.5%, fistulotomy for complex anal fistulas has a rate of over 50%. For this reason, sphincter-sparing approaches to anal fistulas are now the standard of care for patients with anal fistulas involving a significant amount of anal sphincter muscle.

COMMON SYMPTOMS AND THEIR DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pain is one of the most common presenting symptoms of anorectal disorders. The common causes of anorectal pain are shown in Table 31–1. The vast majority of patients have either thrombosed external hemorrhoid, anal fissure, or anorectal abscess. The other causes of anorectal pain are relatively unusual. The etiology of anorectal pain can often be determined with a careful history that is then confirmed with the physical examination.

For patients with anorectal pain, the most important aspects of the patient history are the nature and onset of the pain and any associated symptoms. If the pain is acute in onset (< 1-3 d) and associated with a lump at the anus, a diagnosis of a thrombosed external hemorrhoid is highly likely. If the pain is acute in onset and associated with fever and swelling at the anus, then an anorectal abscess should be suspected. Finally, if the pain is described as a “cut,” “tear,” or “sharp as a knife” and associated with bowel movements, then an anal fissure is the probable cause. Inspection alone will usually confirm the suspected diagnosis as an external hemorrhoid, abscess or cellulitis or anal fissure will be present. It is important to efface the anus by pulling the gluteal cheeks apart in order to identify an anterior or posterior anal fissure that occurs just inside the anal canal. Most patients with anorectal pain cannot tolerate a digital examination and anoscopy but fortunately these evaluations are often unnecessary. If after obtaining a history and carefully inspecting the anus and the diagnosis is still in doubt, an examination under anesthesia may be indicated as small number of patients may have an intersphincteric or supralevator abscess that usually cannot be diagnosed by inspection alone.

Bleeding is the most common presenting symptom in patients with anorectal disorders. Common causes of anorectal bleeding are shown in Table 31–2. While a careful history may suggest the etiology of bleeding, patients can tolerate and require a thorough physical examination as well as anoscopy and lower endoscopy. Even if anorectal pathology is identified on physical examination or anoscopy, endoscopic evaluation is always necessary in order to rule out proximal pathology such as polyps or cancer.

In patients with anorectal bleeding, the history can help identify the source of the bleeding by fully characterizing the amount, timing and location of the bleeding. Blood seen just on the toilet paper suggests anal canal pathology whereas blood seen mixed with the stool suggests a more proximal bleeding source. Inspection of the anus may reveal prolapsing hemorrhoids, an anal fissure, an anal fistula, or anal ulcer. Anoscopy is necessary to evaluate for possible internal hemorrhoids and distal proctitis. Flexible sigmoidoscopy is typically recommended for younger patients (< 40 years old) who do not have a family history of colon cancer. Colonoscopy is recommended for patients over age 40 with anorectal bleeding or patients under age 40 who have a family history of colon cancer. While these general guidelines are appropriate for most patients, the choice between flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy is individualized to each patient’s clinical scenario.

Most anorectal mass lesions are either anal skin tags, a thrombosed external hemorrhoid or a sentinel pile associated with an anal fissure (Table 31–3). In addition to the history, physical examination and anoscopy, most patients with mass lesions need either flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy depending on their age, diagnosis, and whether or not there is a family history of colon cancer. The unusual tumors such as lipoma and GIST that occur deep to the skin, anoderm, and rectal mucosa are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. These tumors often require additional preoperative anatomic evaluation with transanal ultrasonography and/or pelvic MRI to determine their extent and relationship to the anal sphincter muscles.

Discharge from the anus is a relatively common complaint and has a wide range of possible etiologies (Table 31–4). The most common causes of anorectal discharge are mucosal prolapse, anal fistula, and fecal leakage. Patients with anal fistula often have a history of perirectal abscess. On examination, the patient should be asked to strain in order to identify mucosal and rectal prolapse. Anal sphincter tone should be assessed during the digital examination. In patients with previous anorectal surgery, careful inspection of the anus is important to identify any anal contour abnormalities (keyhole deformities). In addition to anoscopy, most patients will require lower endoscopy. Patients with fecal leakage or incontinence often require further functional and anatomic studies.

HEMORRHOIDS

Hemorrhoids are blood vessels in the lower rectum and anal canal. They are not veins but rather arteriovenous connections with pulsatile flow. External hemorrhoids are located below the dentate line and anatomically identified by the presence of anoderm or skin overlying the hemorrhoidal vessel. Due to either diarrhea, constipation, or straining, a hemorrhoidal vessel can become thrombosed with a clot resulting in a painful lump and possibly some bleeding if the clot ruptures through the anoderm. External hemorrhoids typically cause symptoms when they thrombose, prolapse, or cause irritation/hygiene difficulties. Internal hemorrhoids originate from above the dentate line and are covered by mucosa. These blood vessels can become enlarged/engorged (eg, pregnancy) and/or their anchoring muscle, the Treitz muscle, can become weakened (eg, straining, constipation). When either one or both of these circumstances occur, the hemorrhoidal vessels can prolapse into the lumen of the anal canal as well as can prolapse externally. This mechanical prolapse of hemorrhoidal vessels can cause bleeding, irritation, and pressure-like pain.

Internal hemorrhoids can be classified as grade I-IV by their symptoms and degree of prolapse. Grade I hemorrhoids are prominent but do not prolapse. Grade II hemorrhoids prolapse but spontaneously reduce. Grade III hemorrhoids prolapse but require manual reduction. Grade IV hemorrhoids prolapse and cannot be manually reduced. The four-level grading system helps guide the choice of treatment of hemorrhoids.

Patients with thrombosed external hemorrhoids complain of acute pain and swelling or lump at the anus. Patients with external hemorrhoid skin tags will have more chronic symptoms of prolapsed, “extra skin,” irritation, and difficulty with hygiene after bowel movements. Patients with internal hemorrhoids complain of bleeding, pressure-like pain and prolapse. Patients with bleeding internal hemorrhoids can have significant blood loss and become anemic acutely or chronically. Other than thrombosed external hemorrhoids, patients with hemorrhoids do not complain of sharp pain but rather bleeding, prolapse, irritation, and sometimes a pressure-like pain due to the prolapse. Both external and internal hemorrhoids can become incarcerated and gangrenous resulting in necrosis of skin and mucosa as well as bleeding.

Examination of the patient with a thrombosed external hemorrhoid reveals a purple swelling at the anus consistent with a clot in an external hemorrhoid vessel. Patients with external prolapse and tags reveal chronic protrusion and lumps without acute pain and discoloration. Patients with internal hemorrhoids may reveal nothing externally unless the internal hemorrhoids prolapse externally. Digital evaluation of the rectum can rule out any mass lesions or malignancy but internal hemorrhoids cannot be assessed adequately using digital rectal examination. Anoscopy is necessary to properly evaluate internal hemorrhoids. The examiner asks the patient to push or strain while visualizing each of the three common hemorrhoidal piles in the right anterior, right posterior and left lateral positions within the anal canal. Internal hemorrhoids are present if prolapse or bleeding occurs in any of the three locations visualized during anoscopy. Physical examination alone establishes a diagnosis of hemorrhoids. Further evaluation with laboratory or imaging studies is unnecessary unless there has been significant hemorrhage. All patients should also undergo evaluation of the more proximal colon with flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy as indicated.

Since patients and many primary care providers identify any anorectal symptom as being due to hemorrhoids, nearly all patients complain of “hemorrhoids” or will have been told that they have “hemorrhoids.”

Patients with rectal bleeding need to be carefully evaluated not only with anoscopy but also with flexible endoscopy to rule out proximal pathology such as colitis, polyps or cancer. Patients with rectal bleeding, under age 40 and without a family history of colon cancer, can undergo anoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Patients with rectal bleeding between 40 and 50 years of age need evaluation with anoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy with colonoscopy preferred for most patients. Patients over age 50 with bleeding need to be evaluated with anoscopy and colonoscopy. Finally, all patients with a significant family history of colon cancer should undergo anoscopy and colonoscopy regardless of age. Thus, it is very important in patients with rectal bleeding to evaluate the whole colon in most circumstances in order to rule out malignancy.

In patients with symptoms of prolapse, the surgeon must differentiate hemorrhoidal prolapse from true rectal prolapse. Patients with hemorrhoidal prolapse have prolapsing hemorrhoids in one or more of the standard hemorrhoid locations—right anterior, right posterior, and/or left lateral position. Because the hemorrhoids prolapse in these specific locations, the examiner sees prolapsing mucosa and underlying hemorrhoidal vessels with radial folds between the various prolapsing hemorrhoids. Patients with true rectal prolapse have circumferential prolapse of mucosa and full-thickness rectal wall that results in concentric folds. Patients with full-thickness rectal prolapse have decreased sphincter tone whereas patients with prolapsing hemorrhoids typically have normal to increased sphincter tone.

Patients with chronic tags and external hemorrhoids are treated with reassurance particularly if the tags are small and minimally symptomatic. If they have symptoms of irritation, topical hydrocortisone cream can be helpful. If the external hemorrhoids are causing recurring symptoms of irritation, discomfort, and difficulty with anal hygiene then simple surgical excision may resolve them. If a patient with a thrombosed external hemorrhoid is seen within 3 days of the onset of symptoms then excision of the clot may be beneficial. Excision of the clot in these patients who present early to the surgeon allows for faster resolution of their symptoms. Simple incision of the clot is associated with a higher recurrence rate so if surgical intervention is undertaken it should be complete excision of the hemorrhoidal vessel and clot. Most patients with thrombosed external hemorrhoids seek medical attention after 3 days of symptoms. Surgical excision will not hasten resolution of symptoms in these patients, and management is topical and oral pain medications, stool softeners and laxatives. The clot typically resolves in 2 weeks-2 months. After resolution of their clot, occasionally patients are left with a residual skin tag. Hemorrhoidal disease is common during pregnancy and can be treated postpartum if symptoms persist.

Patients with mild to moderate internal hemorrhoids (grades I-II) and constipation are treated with fiber, fluids, and possibly laxatives to improve their bowel habits. For most of these patients this medical treatment to improve their bowel function will resolve their hemorrhoidal symptoms. For patients with “hemorrhoids” and hyperactive bowel function, treatment should be directed at the cause of the diarrhea/multiple bowel movements. These patients should not undergo hemorrhoid surgery. Patients with normal bowel habits and persistent hemorrhoidal symptoms are candidates for a surgical approach.

Internal hemorrhoids can be treated with in-office procedures such as rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation. Most patients with grades I-III hemorrhoids can be successfully treated with office-based procedures. Of the office-based procedures, rubber band ligation is typically the most effective option.

Small to moderate-sized symptomatic internal hemorrhoids (grades I-III) can be treated with rubber band ligation. This in-office treatment involves placement of an anoscope then grasping the largest hemorrhoidal pile above the dentate line with a clamp and then using a rubber band ligator to place a rubber band around the “neck” of the hemorrhoid. Because the rubber band is placed above the dentate line, patients can tolerate this procedure without anesthesia and usually do not have significant postprocedure pain. After banding patients have either no symptoms or a mild to moderate pressure sensation that resolves in hours to a day or two. The rubber band is a noose around the hemorrhoid’s “neck,” and the hemorrhoid and rubber band will fall off within 5-10 days resulting in a scar that reduces the hemorrhoid size and degree of prolapse. When this sloughing of the hemorrhoid and rubber band occurs, the patient may experience bleeding that occasionally is severe enough to require an emergent visit. Patients are banded without antibiotics as sepsis after banding is exceedingly uncommon. Since post-banding sepsis presents with urinary retention, fever and increasing pain, any rubber band ligation patient with this constellation of symptoms needs to be evaluated urgently. Treatment of post-banding sepsis requires intravenous antibiotics, band removal, debridement of necrotic tissue and supportive care in an intensive care unit. Banding is usually performed one “pile” at a time but placement of multiple bands at one setting is possible. Postbanding instructions include keeping the stools soft, using pain medication as needed and returning for urgent reevaluation if signs and symptoms of sepsis develop. Rubber band ligation is well-tolerated and quite successful for patients with grades I-III internal hemorrhoids.

Sclerotherapy involves using anoscopy to inject a sclerosing agent into the apex of grades I- II internal hemorrhoids. A variety of sclerosing agents have been used with a commonly used option being phenol in oil. Typically, 3-5 mL of sclerosing solution is injected. While the initial success rate approaches that of rubber band ligation, recurrences are common. Complications are unusual but necrosis, rectal perforation, and sepsis have all been reported.

Infrared coagulation involves application of infrared energy directly to the internal hemorrhoids with an infrared coagulation probe. Using anoscopy, the probe is placed on the hemorrhoid for 1-2 seconds which results in coagulation of the hemorrhoid with a decrease in size and blood flow through the hemorrhoid. Recent studies have shown that infrared coagulation is as good as rubber band ligation for patients with grades I-II internal hemorrhoids. Complications are unusual but include bleeding, necrosis, and sepsis.

Patients with persistent symptoms despite in-office treatment of their hemorrhoids are candidates for surgery in the operating room. Surgery is usually performed only for patients with grades III-IV internal hemorrhoids. In the operating room, surgical treatment of internal hemorrhoids can be by surgical excision, stapled hemorrhoidopexy or doppler-guided ligation.

Classic excisional hemorrhoidectomy is performed either in the lithotomy or prone position. After the induction of anesthesia the hemorrhoidal piles are excised with scissors, cautery or harmonic scalpel. The resulting wounds are closed, partially-closed or left open depending on surgeon preference. Care is taken to excise just the mucosa, submucosa, and hemorrhoids and to avoid injury to the underlying anal sphincter muscle. In addition, care is taken not to excise too much mucosa and anoderm as this could result in anal stenosis. The procedure takes less than an hour and is scheduled as outpatient surgery. Given that the incisions start externally and end in the anal canal/lower rectum, patients can have significant discomfort postoperatively. Adequate pain control, keeping the bowel movements soft and avoiding constipation are all important postoperatively. Early complications after excisional hemorrhoidectomy include bleeding, infection, and urinary retention. The rate of urinary retention can be reduced by limiting the amount of intravenous fluids during surgery. Late complications include anal stenosis and mucosal ectropion and whitehead deformity (circumferential mucosal ectropion). Given its high success rate and low recurrence rate, all other surgical interventions are compared to excisional hemorrhoidectomy to determine their efficacy.

A stapled hemorrhoidopexy is useful for patients with circumferential grade II-III hemorrhoids who fail in-office treatment. The technique involves placement of a purse-string suture 3-4 cm above the dentate line in the submucosal plane. The circular stapler’s anvil is then placed proximal to the purse string suture and the suture is tied drawing the internal hemorrhoids into the circular stapler. The stapler is then closed and fired removing a circumferential strip of internal hemorrhoids. The staple line, 1-2 cm above the dentate line, is inspected and any bleeding oversewn. Thus, the procedure removes a strip of internal hemorrhoids and creates a hemorrhoidopexy at the staple line that reduces hemorrhoidal prolapse. The procedure does not address external hemorrhoids and thus would not be useful for patients with significant external hemorrhoidal disease. Because the procedure’s incision (at the staple line) is above the dentate line, stapled hemorrhoidopexy is associated with less pain and discomfort than traditional excisional hemorrhoidectomy. The results of stapled hemorrhoidopexy have been good and are comparable to excisional hemorrhoidectomy. Complications from stapled hemorrhoidopexy are also comparable to excisional hemorrhoidectomy with the exception of including some unique complications such as recto-vaginal fistula and rectal obstruction. Appropriate patient selection and meticulous surgical technique are required to achieve the best results with stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Thus, stapled hemorrhoidopexy is a good option for grade II-III internal hemorrhoids that are not associated with significant external hemorrhoids.

Doppler-guided hemorrhoidectomy involves the use of a specially designed anoscope with a doppler probe that allows for precise identification and ligation of the hemorrhoidal vessels. Six to eight hemorrhoidal vessels are identified and suture ligated using the doppler probe to identify the vessels and then confirm the interruption of blood flow after suture ligation. Early results have demonstrated that this technique is comparable to excisional hemorrhoidectomy for grade II-III internal hemorrhoids. The complication profile is also favorable. More experience with the doppler-guided hemorrhoidectomy is necessary in order to adequately evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the procedure.

The successful treatment of external and internal hemorrhoids is related to changing the patient’s bowel habits. Increasing dietary fiber, decreasing constipating foods, introducing exercise, and decreasing time spent on the toilet all decrease the amount of time spent straining in the squatting position. These behavioral modifications are the most important steps in preventing recurrence.

ANAL FISSURE

An anal fissure is a tear in the anoderm usually located in the posterior or anterior midline of the anal canal. An anal fissure may be associated with a sentinel tag located at the distal aspect of the anal fissure (anal verge) and/or a hypertrophied anal papilla at the proximal aspect of the fissure. The inciting event causing an anal fissure is thought to be trauma to the anal canal from a hard bowel movement or other cause. This trauma results in a tear that leads to pain and spasm of the internal anal sphincter muscle particularly during and after bowel movements. The spasm results in elevated anal resting pressures that can unfortunately lead to a vicious cycle of further spasm and pain. With elevated resting pressures, the blood flow to the posterior and anterior midline decreases inhibiting healing of the fissure. Fissures are usually classified as either acute with symptoms occurring just over the past month or chronic with symptoms present for greater than 2-3 months. Over 90% of fissures are located in the posterior midline with the rest located in the anterior midline. Given their etiology of spasm and elevated resting pressures resulting in decreased blood flow, chronic anal fissures can be considered “ischemic ulcers” of the anal canal.

Patients with an anal fissure complain of sharp pain with or immediately after bowel movements. They may also complain of rectal bleeding and a “hemorrhoid” or sentinel tag. Patients often describe moderate to severe pain like a “knife” or “razor blade” during defecation. Due to the pain, patients fear going to the bathroom that can result in delaying defecation, hardened stool, and additional pain. On inspection of the external anus, there may be a sentinel tag in either the posterior or anterior midline. To visualize the fissure, the examiner needs to evert the anus by pulling the right and left anal margin skin laterally. As the anus is everted, the examiner can carefully inspect the anoderm in the posterior and anterior midline for a tear in the anoderm. Patients with significant pain and spasm may not even tolerate this maneuver. In these patients it is helpful to gently expose the anus and ask the patient to strain to defecate to see if during straining self-eversion of the anus occurs. Due to pain, digital rectal examination, and anoscopy are not performed immediately, but reserved for when the symptoms resolve or the patient is in the operating room. Laboratory and imaging studies are not necessary but flexible endoscopy of some type should be scheduled if it has not been performed recently.

Classic anal fissures occur in either the posterior (90% +) or anterior (1%-10%) midline. Not all posterior and anterior anal canal tears are anal fissures. Anal canal ulcers can occur from Crohn disease, leukemia, HIV, cancer and infections such as herpes, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, and tuberculosis. These anal canal ulcers mimic anal fissures. A careful history can help identify possible etiologies of an anal ulcer. On the other hand, typical anal fissures are associated with increased sphincter tone so any patient with decreased sphincter tone should be suspected of having an anal canal ulcer rather than a fissure. Further, whenever a “fissure” is located laterally rather than in the posterior or anterior midline, an anal canal ulcer should be suspected. There should be a low threshold to suspect an anal ulcer rather than fissure. In these patients, an examination under anesthesia with biopsy of the ulcer is necessary to rule out an infectious or malignant etiology.

In addition to causing pain and bleeding, anal fissures can become infected and develop a fissure-fistula complex. This relatively unusual complication is easily treated with a posterior intersphincteric fistulotomy.

The pathogenesis of an anal fissure is pain and spasm resulting in increased internal anal sphincter (IAS) muscle pressures, decreased blood flow, and a nonhealing fissure in the anoderm of the anal canal. Treatment is directed at breaking this pain and spasm cycle to relax the internal sphincter muscle, increase blood flow, and allow the fissure to heal. To do this, patients should keep their stools soft with stool softeners and laxatives to avoid further anal canal trauma. In addition, warm baths are recommended to relax the sphincter muscle and allow the fissure to heal. Stool softeners, bulking agents, and sitz baths will heal 90% of anal fissures. Topical ointments can also be prescribed to decrease the anal sphincter pressure. Nitroglycerin ointment (0.2% or 0.4%) or calcium channel blocker ointment (0.2% diltiazem gel) can be used to chemically relax the IAS muscle. Side effects include headache which occurs more frequently after nitroglycerin ointment. Patients who fail this regimen and have a persistent fissure are candidates for surgery or treatment with botulinum toxin. Botulinium toxin injection into the anal sphincter can be successful but is costly and has a higher recurrence rate than surgery. Thus, medical treatment of anal fissures includes stool softeners, bulking agents, warm baths, topical nitroglycerin ointment or diltiazem gel, and possibly botulinum toxin injection. Most patients with acute anal fissures and over 50% of patients with chronic anal fissures are successfully treated without surgery. Patients who fail medical management of their anal fissure should undergo surgical intervention.

Surgical treatment of an anal fissure involves performing a lateral internal sphincterotomy. While the fissure may be biopsied and a sentinel tag or hypertrophied anal papilla excised, the most important part of an operation for anal fissure is directed via a lateral incision at the IAS muscle. In the operating room, a lateral incision is made in the intersphincteric groove between the internal and EAS muscles and a submucosal and intersphincteric dissection is performed in order to clearly identify the IAS muscle. The IAS muscle is then cut the length of the fissure in order to permanently relax the anal canal. After sphincterotomy, relaxation of the anal canal is readily appreciated by the surgeon. This short, outpatient operation has over a 90% success rate and a recurrence rate of less than 10%. Patients often have less pain after surgery. Complications include bleeding, infection, and rarely fecal incontinence (< 0.5%).

Patients who have preexisting fecal leakage or lack increased anal sphincter muscle pressures are poor candidates for lateral internal sphincterotomy which could result in worsening bowel control. These relatively rare patients are better treated with an anal advancement flap that does not involve dividing any sphincter muscle. For a description of the anal advancement flap, see the section on anal stenosis.

ANORECTAL ABSCESS & FISTULA

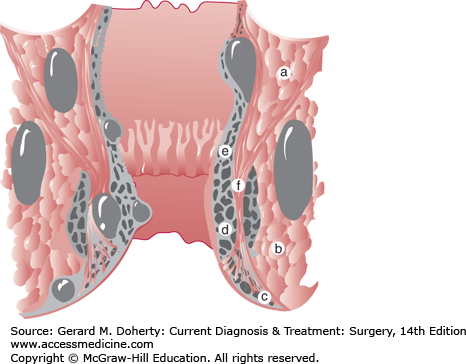

An anorectal abscess is one of the three common causes of anorectal pain and is the only cause that usually requires urgent surgical treatment. Most anorectal abscesses have a cryptoglandular etiology. When the anal glands in the crypts of the dentate line become blocked, an anorectal abscess can develop. Because these glands extend a variable depth, the developing abscess can track in various anatomic planes. Abscesses are classified by their anatomic location:—perianal, ischiorectal, intersphincteric, and supralevator (Figure 31–3). Fortunately, most abscesses are perianal or ischiorectal and can be relatively easily identified on physical examination. Intersphincteric and supralevator abscesses are unusual and often are only identified by MRI/CT or examination under anesthesia. Most abscesses are cryptoglandular in etiology but some patients develop abscesses related to another disease process such as Crohn, tuberculosis, and cancer. While many abscesses will heal with simple incision and drainage, some 30%-60% of abscesses will not heal and patients will complain of persistent drainage and recurrent inflammation related to an anal fistula. In these patients, the cryptoglandular source and external surgical drainage site remain connected allowing for passage of mucus and stool through this tract. The location of the abscess, thus, determines the location and tract of the resulting anal fistula. Anal fistulas are classified by their relationship with the anal sphincter muscle—intersphincteric, transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric. Due to the frequency of the abscesses that created them, intersphincteric and transsphincteric fistulas are the most common anal fistulas. Suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric fistulas are exceedingly rare. Due to their relationship with the anal sphincter muscle, treatment of anal fistulas should be evaluated and treated by highly specialized surgeons familiar with sphincter-saving techniques in order to avoid complications such as fecal incontinence. Since fistulas occur in 30%-60% of patients after anorectal abscess drainage, patients undergoing abscess drainage should be warned about the possibility of a fistula and should be given appropriate follow-up to insure healing and absence of a persistent fistula tract.

Patients with an anorectal abscess complain of acute pain, swelling, and possibly a fever. An occasional patient may complain of leakage of mucus and pus related to the spontaneous drainage of the abscess. For patients with perianal and ischiorectal abscesses, physical examination often reveals erythema, fluctuance, and asymmetry between the right and left perirectal tissues. An occasional patient will present with a symmetric horseshoe abscess cavity circling half or more of the circumference and may have no left-right asymmetry. If a patient has an intersphincteric or supralevator anorectal abscess, there is often none of the above findings on physical examination. Thus, patients with a suspicion of an abscess but no obvious physical examination findings should either be imaged with MRI or taken to the operating room for an examination under anesthesia. Laboratory testing is usually not helpful in patients with an anorectal abscess although frequently these patients will have an elevated white blood cell count. Radiologic studies are also not necessary as the vast majority of anorectal abscesses are obvious on the basis of history and physical examination alone. Some patients with symptoms of an abscess and no physical examination findings may benefit from imaging studies as well as patients with recurrent or complex abscesses such as some patients with Crohn disease. Potential imaging studies include CT, MRI, and anorectal ultrasound. Anorectal ultrasound is not well tolerated in patients with an acute abscess and CT will miss some abscesses. Thus, if an imaging study is necessary, an MRI is the imaging test of choice being able to readily identify complex abscesses and their anatomic extensions.

Patients with an anorectal fistula complain of chronic drainage of mucus and blood, irritation, and usually have an antecedent history of an anorectal abscess. If a patient has persistent drainage 6-8 weeks after abscess drainage, then a fistula should be suspected, and evaluation and treatment for an anal fistula should be initiated. Some patients with anal fistulas will have a relatively remote or no history of an abscess. Physical examination reveals the external opening and often there is a palpable subcutaneous tract between the external opening and the anus. It is important to remember that any nonhealing wound or opening around the anus should be presumed to be a fistula until proven otherwise. Laboratory testing is not necessary in patients with anal fistulas but imaging studies may be useful for recurrent and complex anal fistulas. MRI is the imaging procedure of choice to identify anal fistula tracts, side tracts, and the relationship of the tracts to the anal sphincter muscle. Transanal ultrasonography can also be useful and can be performed intraoperatively using hydrogen peroxide enhancement to highlight the fistula tract.

The differential diagnosis for patients with anorectal abscess or fistula includes perianal hidradenitis, pilonidal disease, and rarely bartholin gland cyst. On physical examination, it may be difficult to differentiate an anorectal abscess/fistula from complex hidradenitis or pilonidal disease. Further, hidradenitis or pilonidal disease can occur concurrently with an anorectal abscess or fistula. Careful evaluation in the operating room is necessary to determine if an abscess is communicating only with the skin (hidradenitis), only with the midline gluteal cleft (pilonidal disease) or with the anus (fistula). Rare causes of anorectal abscesses and fistulas include tuberculosis, actinomycosis, cancer, and diverticulitis.

Abscesses can enlarge and spread along various anatomic planes around the anus. Abscesses can form a posteriorly based horseshoe around the anus usually just sparing the anterior perirectal space. Abscesses can also track around just one side of the anus (1/2 horseshoe). While it may be unusual for a single abscess to destroy a significant amount of anorectal tissue and diminish anorectal function, multiple recurrent abscesses can result in destruction of anorectal anatomy and muscle function resulting in a deterioration of anorectal function.

In rare circumstances, an anorectal abscess can result in systemic sepsis. Treatment should include adequate drainage of the abscess, intravenous antibiotics, and supportive intensive care unit care.

Anorectal abscesses can recur after treatment. The reasons for recurrence include inadequate initial drainage (often because deep postanal space was not drained), the presence of a fistula, and Crohn disease. Nearly all patients with recurrent or complex abscesses should be evaluated for Crohn disease.

Anal fistulas should be treated when identified because although they may be minimally symptomatic they can develop into an acute anorectal abscess. Fistulas, too, may recur after treatment due to undiagnosed side tracts or Crohn disease. Crohn disease should be ruled out in all patients with complicated or recurrent anal fistulas.

Anorectal abscesses are treated by incision and drainage. For the common perianal and ischiorectal abscesses, a cruciate incision is made over the area of fluctuance as close to the anal verge as possible to decrease the length of a fistula tract if one should develop. Frequently it is useful to excise the skin tips of the cruciate incision in order to allow for adequate drainage and insure that the abscess heals from the inside out as premature skin healing could result in a recurrent abscess. When draining an acute abscess, it is very unlikely to be able to identify an internal opening and the course of the fistula tract if one is present. Thus, when draining an abscess either in the office or the operating room, it is important to concentrate effort at insuring that the abscess is adequately drained and worry about a fistula later if it should develop. For the relative rare intersphincteric abscess, transanal drainage is performed. In the operating room, the intersphinteric abscess is palpated within the anal canal and via an anoscope a longitudinal incision is made to drain the abscess internally into the rectum. Supralevator abscesses can also be treated in this way. Alternatively, supralevator abscesses can be drained in the interventional radiology suite using CT-guidance but this may result in an extrasphincteric fistula if the etiology of the abscess is cryptoglandular.

After surgical drainage, only immunocompromised patients or patients with associated sepsis are treated with antibiotics. For large abscesses, placement of a penrose or mushroom-catheter drain may be necessary to insure adequate drainage. After draining a horseshoe abscess posteriorly, it is useful to make counter incisions at the anterior extent of the abscess on both sides of the anus and put looped penrose or vessel-loop drains from the posterior opening to the anterior opening. These drains are left for at least 2-3 weeks and will allow for better drainage of the entire abscess cavity. Finally, follow-up of patients after abscess drainage is important to insure that the abscess completely heals and does not evolve into a persistently draining fistula tract.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree