The Institute of Medicine’s To Err Is Human (National Academy Press, 2000) called for a 50 percent reduction in medication errors, but in 2009, Dr. David Bates said, “With respect to the 50 percent reduction, the truth is that we don’t really know, because we don’t have good metrics for sorting out how common medical errors are in most institutions.” Atul Gawande reported in Complications (Holt, 2003) that autopsies turned up major misdiagnoses as the cause of death a shocking 40 percent of the time, and rates have not improved since 1938.

This shows up in many ways:

Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs)

Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs)

Bloodstream infections (BSIs)

Bloodstream infections (BSIs)

Surgical-site infections (SSIs)

Surgical-site infections (SSIs)

Pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers

Surgical errors: retained foreign objects, surgical infections, and wrong-site and wrong-patient surgeries

Surgical errors: retained foreign objects, surgical infections, and wrong-site and wrong-patient surgeries

Blood incompatibility

Blood incompatibility

Ventilator-acquired pneumonia (VAP)

Ventilator-acquired pneumonia (VAP)

Patient falls

Patient falls

Medication errors

Medication errors

A recent RAND study found that only one of every two patients will receive care that meets generally accepted standards: 30 percent of stroke patients, 45 percent of asthma patients, and 60 percent of pneumonia patients. In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 1.7 million healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) resulted in 99,000 deaths (271 per day—this is equivalent to a 747 crashing every day) and an additional $35.7 billion to $45 billion in unnecessary costs per year. Between 2004 and 2006, 238,337 preventable deaths occurred involving the Medicare population. In addition, 4.5 patients per 100 admissions will acquire an infection while in the hospital. Types and number of HAIs and estimated costs per patient are as follows: SSIs—290,485 at $34,670; BSIs—92,001 at $29,156; VAP—52,543 at $28,508, UTIs—449,334 at $1,007; and Clostridium difficile–associated disease (CDI)—178,000 at $9,124.

MEMORIAL HERMANN CASE STUDY

We can’t make our employees perfect, but we can develop processes that encourage a level of mindfulness that enables us to catch potential errors before they do harm.

In 2006, Memorial Hermann Health System implemented a high-reliability organization (HRO) program called “Breakthroughs in Patient Safety (BIPS)” using experts from nuclear power, commercial aviation, and other HROs to teach employees how to perform tasks in a safe, highly reliable manner. Becoming an HRO requires implementation “from the boardroom to the bedside.”

Memorial Hermann’s quality and patient safety results are impressive. Working across nine acute care and two rehabilitation hospitals plus over a hundred ambulatory facilities, Memorial Hermann has chased the goal of zero harm. From 2007 to 2013, more than 827,000 transfusions were administered with zero cases of blood incompatibility. Several of the hospitals have gone years with zero VAP cases or central line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) cases. Serious medication errors decreased to zero for most months, even though more than a million medications are administered per month (http://www.memorialhermann.org/about-us/quality-report-high-reliability-interventions-and-process-improvements/). Six Sigma is the second step in becoming a HRO.

A BETTER EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT (ED) IN FIVE DAYS

Studies have shown that between 2 and 8 percent of patients with heart attacks who are seen in emergency rooms are mistakenly discharged, and a quarter of these people die or suffer a complete cardiac arrest.

In Complications, Gawande identifies one Swedish study that trained a computer to read ECGs. It outperformed a leading cardiologist by 20 percent.

A BETTER CLINICAL STAFF IN FIVE DAYS

Estimates are that, at any given time, 3 to 5 percent of the practicing physicians are actually unfit to see patients.

Much like a rapid response team (RRT) uses indicators to prevent a code, Dr. Kent Neff identified what he calls “behavioral sentinel events that signal the need for an intervention”: persistent anger, abusive behavior, bizarre or erratic behavior, and violating professional boundaries. Another measure is the number of lawsuits or complaints against a physician.

A BETTER OPERATING ROOM (OR) IN FIVE DAYS

We’ve celebrated cowboys, but what we need is more pit crews.

There are 50 million surgeries each year in the United States, with 150,000 deaths. Estimates for complication rates range from 3 to 17 percent. Worldwide, there are 230 million surgeries leaving 7 million patients disabled and 1 million dead. Research has shown that half of all complications and deaths are avoidable. Surgery has four big killers worldwide:

Infection

Infection

Bleeding

Bleeding

Unsafe anesthesia

Unsafe anesthesia

The unexpected

The unexpected

Atul Gawande, a surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, authored The Checklist Manifesto, a book about using surgical checklists to reduce operating times, infections, and deaths by more than a third. Gawande participated on the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) team to develop a surgical safety checklist, including simple things such as having everyone on the surgical team introduce themselves by their first name. “Giving people a chance to say something at the start seemed to activate their sense of participation and responsibility and their willingness to speak up.” Operating team members’ sense of functioning well as a team jumped from 68 to 92 percent.

A Better OR in Two Minutes

The WHO’s Surgical Safety Checklist and Implementation Manual are available at www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/ss_checklist/en/index.html. Use of the checklist in eight trial hospitals delivered the following results:

A 36 percent reduction in major complications

A 36 percent reduction in major complications

A 47 percent reduction in deaths

A 47 percent reduction in deaths

A 50 percent reduction in infections

A 50 percent reduction in infections

A 25 percent reduction in returns to the OR to fix something missed

A 25 percent reduction in returns to the OR to fix something missed

At Kaiser hospitals in southern California using the checklist, the rate of OR nurse turnover dropped from 23 to 7 percent. Employee satisfaction rose by 19 percent. And staff rating of the “teamwork climate” rose from good to outstanding.

At Kaiser hospitals in southern California using the checklist, the rate of OR nurse turnover dropped from 23 to 7 percent. Employee satisfaction rose by 19 percent. And staff rating of the “teamwork climate” rose from good to outstanding.

The surgical checklist is like a pilot’s checklist; it’s part of how an HRO operates. By the end of 2009, only 10 percent of U.S. hospitals had implemented the checklist. It takes doctors an estimated 17 years to adopt a new treatment.

Gawande says:

In the spring of 2007, I began using … [the surgical checklist] in my own operations. … did I think the checklist would make much of a difference in my cases? No. In my cases? Please. To my chagrin, however, I have yet to get through a week in surgery without the checklist’s leading us to catch something we would have missed.

Want to improve surgical outcomes? Use the WHO’s surgical checklist, and introduce everyone before surgery starts (www.who.int/patient safety/safesurgery/en/). Checklists can be good medicine for doctors, nurses, and patients.

Checklists Are Changing Hospitals

I recently read Peter Pronovost and Eric Vohr’s book, Safe Patients, Smart Hospitals: How One Doctor’s Checklist Can Help Us Change Healthcare from the Inside Out. In case you’ve been hiding under a rock, these authors’ central line checklist virtually eliminated CLABSIs in 77 Michigan hospitals and has been spreading across the nation and around the world. This is it:

- Wash your hands using soap or alcohol prior to placing the catheter.

- Wear sterile gloves, hat, mask, and gown, and completely cover the patient with sterile drapes.

- Avoid placing the catheter in the groin if possible (such placements have a higher infection rate).

- Clean the insertion site on the patient’s skin with chlorhexidine antiseptic solution.

- Remove catheters when they are no longer needed.

The book details Dr. Pronovost’s journey to first eliminate CLBSIs in the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) at Johns Hopkins and then to take it first to Michigan and then to the rest of the world.

Translating Research into Practice (TRIP)

Our success at virtually eliminating central line infections in the SICU created a spark. And we wanted to use this spark to ignite a wildfire of change throughout the hospital and healthcare.

To do this, Pronovost’s team created a structure for figuring out how to “fix” healthcare—the TRIP model:

- Summarize evidence into checklists.

- Identify and mitigate local barriers to implementation.

- Measure performance.

- Ensure that all patients reliably receive the intervention.

As you might imagine, local barriers to implementation are the first challenge. “People don’t fear change; they fear loss.” To minimize fear, focus on minimizing real loss and debunking the mythological fear of loss.

While TRIP teams were successful at reducing CLBSIs and VAP, they hit a wall in the operating rooms. Shaving a surgical site increases the likelihood of a SSI due to small nicks in the skin. Getting surgeons to abandon their razors, even with a mountain of evidence, was almost impossible.

Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP)

The Johns Hopkins safety team reviewed liability claims and errors and found that in 90 percent of the cases, one of the patient’s clinical team members knew that something was wrong and either kept silent or was ignored. “Anywhere teams have to work together to care for patients, bad culture, communication, and teamwork have a negative effect on that care.”

To address this issue, the team developed CUSP to focus on a work unit where culture lives. “The healthcare industry has a strange culture that drives people to believe they are perfect, invincible machines that can work long hours with little sleep and do everything perfectly.”

CUSP teams focus on identifying problems in the unit. They call them defects not errors because people make errors but systems have defects. This simple shift focuses on fixing the system, not people. In an average unit, there may be 20 defects a day. A patient with an infection, for example, will require an antibiotic. If it’s not available in the unit, it may take hours to get the prescription filled from the pharmacy, which threatens the patient. This is a defect, a system problem.

After implementing CUSP countermeasures, length of stay (LOS) dropped by half in the ICU, medication defects dropped from 94 percent to almost zero, and nursing turnover dropped from 9 to 2 percent.

Michigan’s Journey

The Michigan Hospital Association asked Dr. Pronovost to help them reduce CLABSIs. Although it wasn’t easy and all smooth sailing, median CLABSIs dropped from 2.7 infections per 1,000 catheter days to almost zero and have stayed down for four years, saving an estimated 2,000 lives and $200 million a year.

The Challenge

Dr. Pronovost found that physicians skipped at least one step with a third of patients. So why do doctors resist using checklists?

Unlike pilots, doctors don’t go down with their planes.

Dr. Pronovost went on to establish checklists for:

Administering pain medication, which reduced untreated pain from 41 to 3 percent

Administering pain medication, which reduced untreated pain from 41 to 3 percent

Prescribing antacids for ventilation patients to prevent stomach ulcers and elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees to stop secretions from entering the windpipe, reducing pneumonia by 25 percent and preventing 21 deaths

Prescribing antacids for ventilation patients to prevent stomach ulcers and elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees to stop secretions from entering the windpipe, reducing pneumonia by 25 percent and preventing 21 deaths

Use of checklists reduced ICU LOS by half! Combining these checklists with the WHO’s surgical checklist could slash adverse events. Concise checklists for error-prone processes may be the ultimate safety tool for patients and clinicians. Pilots use them to safeguard air travel. What can we learn from their expertise? Memorial Hermann uses the surgical checklist for all surgeries. Shouldn’t your hospital? Consider becoming an HRO!

Between 2003 and 2006, Allegheny General Hospital reduced central line infections by 95 percent and deaths from CLABSI to zero. In 2006, the hospital went a whole year without a central line infection. In 2010, Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York went a whole year without a central line infection in the pediatric ICU while treating 1,647 patients for 2,574 central line days. When the medical center started the program, the central line infection rate was 4.7 per 1,000 central line days. In pediatric patients, maintenance of the line accounts for 90 percent of the infections. The medical center implemented a “scrub the hub” of the catheter port with a special cleaning solution, frequent tubing changes, and a new protocol for changing the catheter dressing.

When a drug trial gets results, it’s easy to see. When a safety improvement is successful, nothing happens. There are no bloodstream infections; there are no medication errors; there are no surgical complications. A nonevent is often invisible. The goal is zero harm.

Retained Foreign Objects

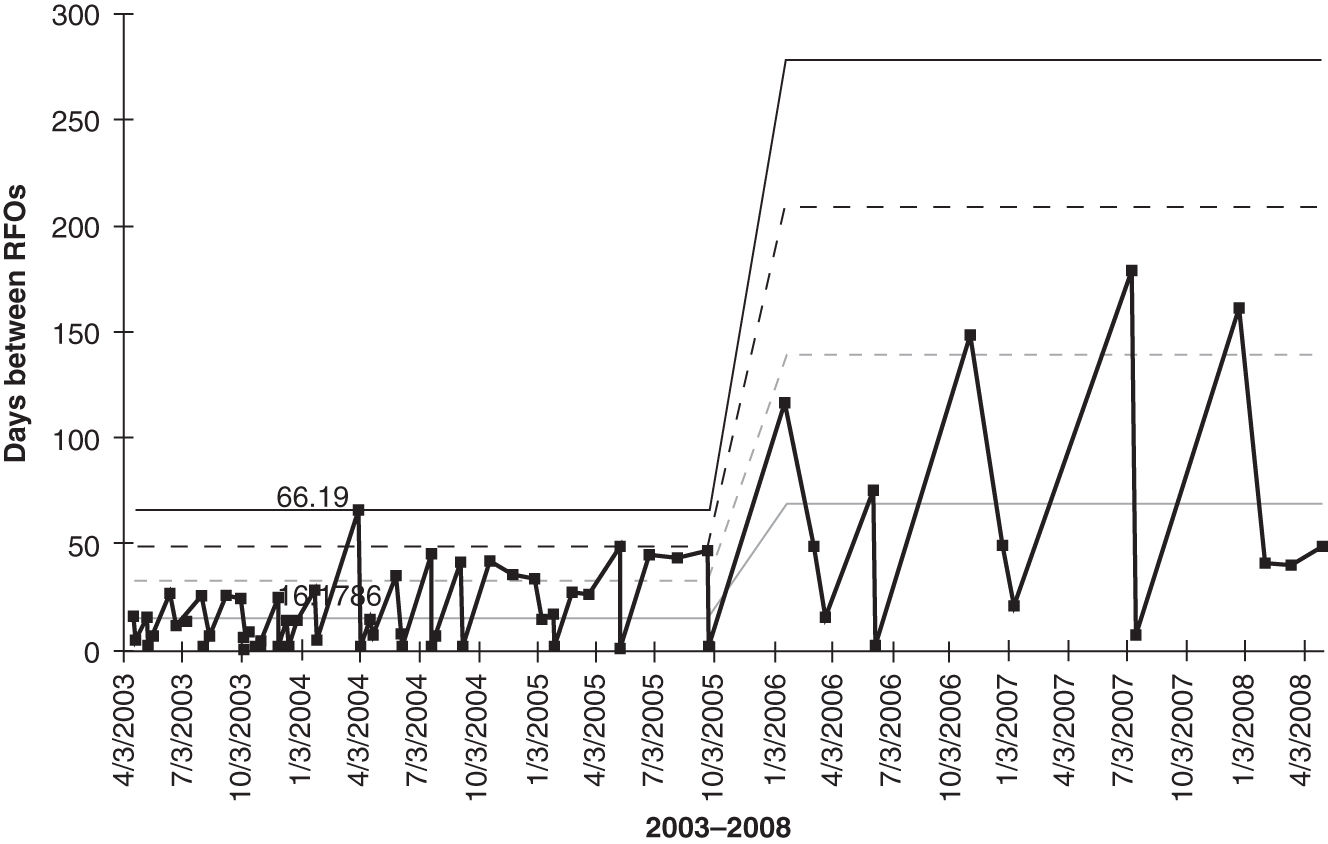

Every 120 minutes, a retained foreign object (RFO) occurs in U.S. surgeries. RFOs (i.e., surgical left-ins) occur in one out of 1,000 (1,000 PPM) abdominal operations, resulting in significant adverse outcomes. In 2005, the Mayo Clinic Rochester averaged one RFO every 16 days. By changing the process for counting and tracking surgical supplies and instruments, the clinic was able to extend time between RFOs to 69 days (Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1

Days between RFOs chart.

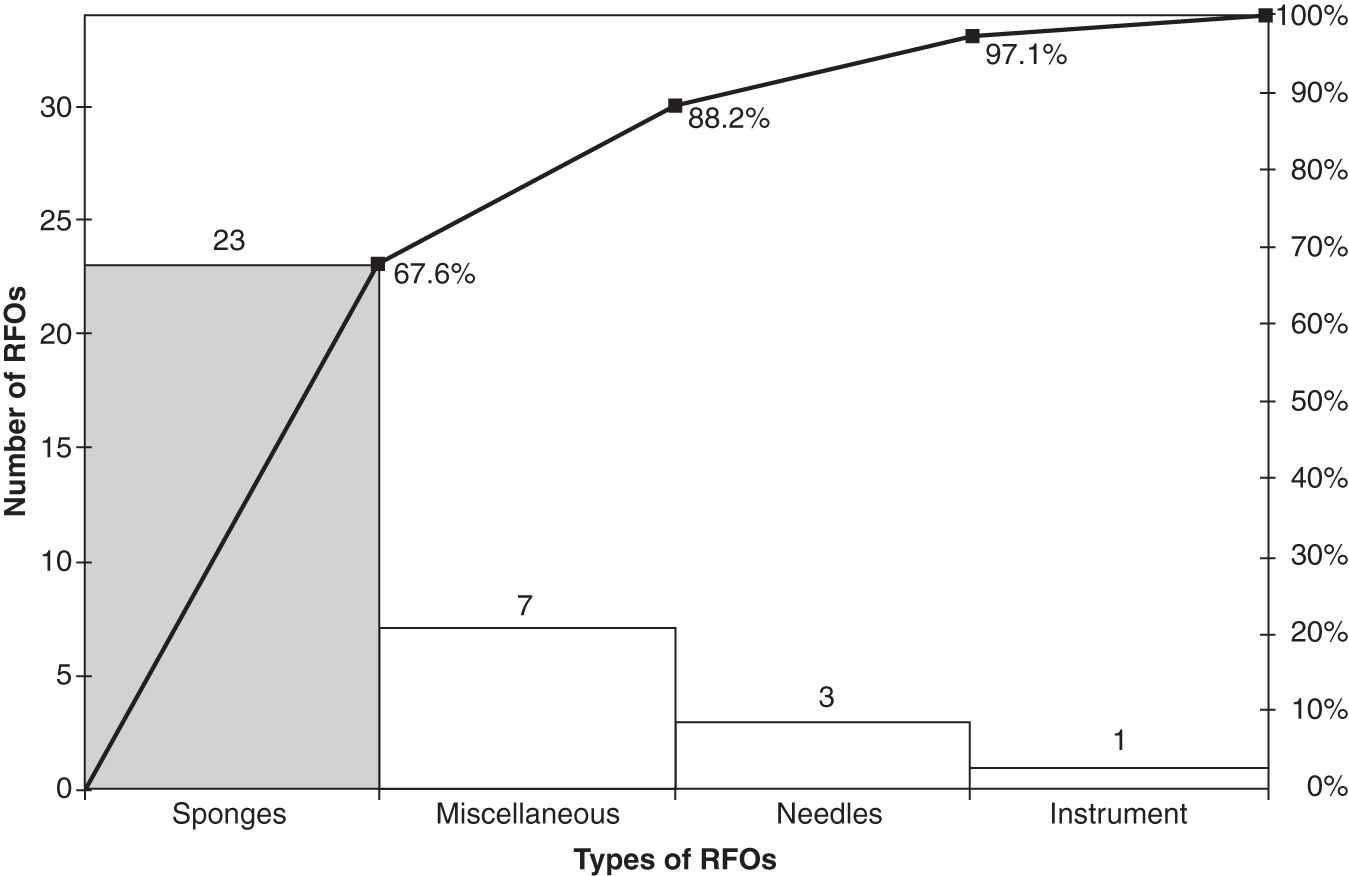

With over 100 unique items employed in surgery, which item was left in most commonly? Sponges (Figure 3.2). Changing the sponge counting process to require an exact match of sponges in and out resulted in far fewer sponge RFOs.

FIGURE 3.2

RFO Pareto chart.

Instead of counting manually, why not use technology? ClearCount Medical Solutions (www.medgadget.com/archives/2010/01/markets_first_rfid_surgical_sponge_tracking_system.html) developed Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved sponges fitted with a radiofrequency identification (RFID) chip that is smaller than a penny. A handheld wand detects commonly used surgical sponges. Here’s what ClearCount identifies as the benefits of using RFID sponges:

Passive: the nonemitting tag contains no battery.

Passive: the nonemitting tag contains no battery.

Small: the RFID tag is the size of a penny.

Small: the RFID tag is the size of a penny.

No line of sight is required to detect the sponges.

No line of sight is required to detect the sponges.

The detector can read multiple sponges simultaneously.

The detector can read multiple sponges simultaneously.

The detector can’t count the same sponge twice.

The detector can’t count the same sponge twice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree