SECTION 3

INDIVIDUAL BIOLOGICAL WEAPON DETAILED QUICK REFERENCES

Aflatoxins

OVERVIEW Aflatoxins are a class of toxins produced by several strains of the common fungus Aspergillus (mostly A. flavus and A. parasiticus). Natural human and animal intoxication occurs from ingesting contaminated grains and nuts such as corn, wheat, Brazil nuts, pecans, pistachio nuts, walnuts, and peanuts, especially when grown during times of drought. In a bioterrorist attack, aflatoxins would most likely be released as an aerosol or droplets with intoxication of the victims occurring by inhalation, ingestion, and/or direct absorption through the skin. The single dose LD50 of aflatoxin ranges from 0.5 to 10 mg/kg. Aflatoxin is known to have been weaponized by the Iraqi biowarfare program.

INCUBATION (LATENT) PERIOD The incubation period is very variable and related to dose and route. It probably lasts for days or weeks. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

Symptoms and Clinical Course3,24

• Initial presentation in a large initial exposure is related to acute hepatic necrosis and consists of fever, jaundice, edema of the limbs, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, pulmonary edema, hemorrhage, hepatomegaly, seizures, coma, and death. In two described outbreaks, the initial mortality rates were 27% and 60%.

• Survivors may progress to fatty liver, cirrhosis, and/or hepatic carcinoma. Pulmonary adenomatosis may occur following inhalational exposure. Many victims recover without apparent sequelae.

DIAGNOSIS3,24 Clinical suspicion is critical, and aflatoxin intoxication should be considered in any cluster of patients with an unexplained acute hepatitis–like illness.

• It must be differentiated from other forms of chemical, toxic, and viral hepatitis.

• An enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has been used to identify aflatoxin B1 in human urine, but it is not generally available.

TREATMENT3 There is no specific treatment or antidote.

• Initiate symptomatic and supportive care only.

• Administer activated charcoal following oral ingestion.

• Check liver function tests at regular intervals as clinically dictated.

• Decontamination of patients’ skin will usually not be necessary, but if required by the presence of residual agent, use only soap and water.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Anthrax (Inhalational and Gastrointestinal)

OVERVIEW Bacillus anthracis is an encapsulated, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus. Spores can survive for decades and are resistant to heat, microwaves, and ultraviolet light. It kills by production of toxins, with nearly 100% mortality if untreated. There are three forms: inhalational, gastrointestinal (GI), and cutaneous, depending on the route of exposure. It may rarely produce a fatal anthrax meningitis.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation is 1–13 days (rarely up to 60 days) for the inhalational form and 3 to 5 days for gastrointestinal anthrax. No person-to-person transmission of inhalational or GI anthrax has been documented. GI anthrax is acquired by ingestion of contaminated food. Inhalational anthrax is the most likely form following an aerosol release in a bioterrorism attack. About 10,000 spores (possibly as few as 100) may produce lethal infection.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE3,6,21,26

• Inhalational anthrax: Initial presentation includes 24–48 hr of nonspecific flulike illness with fever, chills, cough, headache, myalgias, malaise (often profound), and dyspnea. It may also include chest tightness or pleuritic pain. Nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and/or sore throat are uncommon (<20%). Progresses to high fever, extreme fatigue, nonproductive cough, diaphoresis, severe respiratory distress, cyanosis, septicemia, and death.

• Gastrointestinal anthrax: Initial presentation of the intestinal form includes 24–48 hr of fever, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia. Rapidly progresses to hematemesis, hematochezia, and symptoms of acute abdomen (abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding and rebound).

• Without treatment, mortality is nearly 100% from toxemia, sepsis, and septic shock.

• Treatment of both forms is usually futile after predromic period (1–2 days).

• Anthrax may also produce an oral-pharyngeal form with oral and/or esophageal ulcers and regional lymphadenopathy. It has an untreated mortality rate of 50–60%.

DIAGNOSIS3,6,21,26 Diagnosis is based mostly on clinical presentation and history of possible exposure. Chest x-ray (CXR) may show widened mediastinum, mediastinal adenopathy, and/or pleural effusion. Infiltrates may also be present. If CXR results are uncertain, proceed to chest computed tomography (CT). Gram-positive rods can often be seen on peripheral blood smear, and blood cultures are often positive within 12 hr. Presently, PCR is available only through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and certain laboratories.

EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS21,25 Treat for 60 days or until 3 doses of vaccine have been administered.

• Ciprofloxacin 500 mg (peds 10–15 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr (levofloxacin 500 mg PO Q24 hr may be an alternative) or doxycycline 100 mg PO Q12 hr (peds 2.5 mg/kg) Q12 hr or amoxicillin 500 mg PO Q8 hr (peds 40 mg/kg/day divided Q8 hr)

• Acellular vaccine (if available) 0.5 ml SQ at the time of exposure, then at 2 and 4 weeks, and 6, 12, and 18 months. The release of the vaccine for use is controlled by the CDC.

TREATMENT OF ACTIVE ANTHRAX INFECTION21,25 Treat for 60 days, and change IV to PO meds when the patient is stable.

• Ciprofloxacin 400 mg (peds 10–15 mg/kg) IV Q12 hr (levofloxacin 500 mg IV Q24 hr may be an alternative) or doxycycline 100 mg (peds 2.5 mg/kg) IV Q12 hr PLUS rifampin 600 mg (peds 10–20 mg/kg) PO Q day or clindamycin 900 mg IV Q8 hr (peds 5–10 mg/kg Q12 hr) or vancomycin 1 g IV Q12 hr (peds: see PDR) or imipenem 500 mg IM or IV Q6 hr (peds: see PDR) or ampicillin 500 mg IV Q6 hr (peds: see PDR) or clarithromycin 500 mg (p 7.5 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr

• Administer standard symptomatic and supportive therapy for respiratory failure, shock, and fluid replacement.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed). Decontaminate patients with soap and water only. Spores on surfaces can be killed by 10% hypochlorite solution (1 part bleach in 9 parts water).

Anthrax (Cutaneous)

OVERVIEW Bacillus anthracis is an encapsulated, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus. Spores can survive for decades and are resistant to heat, microwaves, and ultraviolet light. Cutaneous anthrax produces skin lesions by entry through an opening in the skin and subsequent release of toxins.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD The incubation period is 1–12 days for cutaneous anthrax. Person-to-person transmission is only by direct contact with a skin lesion and may result in a secondary cutaneous infection.

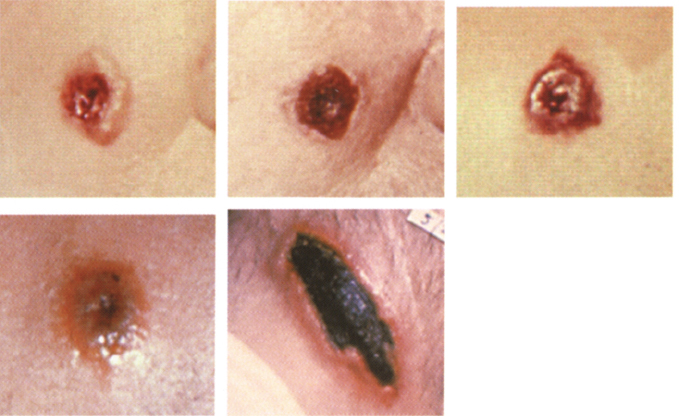

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE3,6,21

• Initial presentation consists of a small pruritic group or ring of papules that evolves to vesicles and then to a small skin ulcer by the second day. Progresses to a depressed black eschar (usually 2–3 cm in size) over 2–5 days. Primarily affects hands, forearms, head, and neck, but may involve chest, eyes, and mouth. Usually resolves in about 2 weeks.

• Without proper treatment, it may lead to a fatal systemic form of anthrax in about 20% of victims. This occurs following progression to a lymphangitis and painful lymphadenopathy that progresses to septic shock.

Photos 1–4 courtesy of the CDC Photo 5 with permission from Biford. Pathology of tropical and extraordinary diseases, vol. 1. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington D.C.

DIAGNOSIS3,6,21 Diagnosis is mostly based on clinical presentation, appearance of the skin lesion, and a history of possible exposure. Gram-positive rods can often be seen on gram stain and/or culture of vesicular fluid. A punch biopsy can also be sent for culture, immunohistochemical staining, and/or PCR (presently available only through the CDC and certain laboratories). Blood cultures should also be obtained before instituting antibiotic therapy.

TREATMENT FOR INDIVIDUAL SMALL LESIONS AND EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS21,25 Treat for 60 days or until 3 doses of vaccine have been administered. All patients with cutaneous anthrax following a bioterrorist attack should be presumed to have also been exposed to inhalational anthrax.

• Ciprofloxacin 500 mg (peds 10–15 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr (levofloxacin 500 mg PO Q24 hr may be an alternative) or doxycycline 100 mg PO Q12 hr (peds 2.5 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr or amoxicillin 500 mg PO Q8 hr (peds 40 mg/kg/day divided Q8 hr)

• Acellular vaccine (if available) 0.5 ml SQ at the time of exposure, then at 2 and 4 weeks, and 6, 12, and 18 months

TREATMENT FOR MULTIPLE EXTENSIVE LESIONS OR LESIONS OF THE HEAD AND NECK21,25 Treat for 60 days, and change IV to PO meds when patient is stable.

• Ciprofloxacin 400 mg (peds 10–15 mg/kg) IV Q12 hr (levofloxacin 500 mg IV Q24 hr may be an alternative) or doxycycline 100 mg (peds 2.5 mg/kg) IV Q12 hr PLUS rifampin 600 mg (peds 10–20 mg/kg) PO Q day or clindamycin 900 mg IV Q8 hr (peds 5–10 mg/kg Q12 hr) or vancomycin 1 g IV Q12 hr (peds: see PDR) or imipenem 500 mg IM/IV Q6 hr (peds: see PDR) or ampicillin 500 mg IV Q6 hr (peds: see PDR) or clarithromycin 500 mg (peds 7.5 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed). Decontaminate patients with soap and water only. Spores on surfaces can be killed by 10% hypochlorite solution (1 part bleach in 9 parts water).

Blastomycosis

OVERVIEW Blastomycosis is produced by the fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is endemic to the southern, eastern, and central regions of North America. It produces a systemic disease with primarily pulmonary and cutaneous findings, but it may infect any organ or system. Clinically apparent illness occurs in fewer than 50% of those with naturally acquired infection, but in a bioterrorism attack, the higher levels of spore exposure attained would likely produce illness in a greater percentage of exposed victims. The mortality rate is about 5%.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD The incubation period is 30–45 days. Infection occurs via inhalation into the lungs of spores contained in dust from organic soil. In a terrorist attack, it would be released as an aerosol, and the incubation period may be reduced as a result of higher levels of spore exposure. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,23

• Initial presentation consists of sudden onset of flulike illness with fever, chills, myalgia, arthralgia, cough, and fatigue.

• May progress to

Pulmonary infection (60% of all cases) with productive cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, pleuritic chest pain, low-grade fever, and dyspnea. CXR may show findings of pulmonary infiltrates, nodules, and/or cavitations. Hilar adenopathy may also be present.

Pulmonary infection (60% of all cases) with productive cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, pleuritic chest pain, low-grade fever, and dyspnea. CXR may show findings of pulmonary infiltrates, nodules, and/or cavitations. Hilar adenopathy may also be present.

Cutaneous infection produces two types of skin lesions occurring mostly on exposed skin of the face and extremities. It may occur along with pulmonary infection:

Cutaneous infection produces two types of skin lesions occurring mostly on exposed skin of the face and extremities. It may occur along with pulmonary infection:

• Small papulopustular lesions that become heaped up and crusted, with a gray to violaceous color

• Small pustules that progress to superficial ulcers with a friable granulomatous base

Skeletal infection produces well-demarcated lytic bone lesions with contiguous tissue abscesses (33% of all patients). It most often affects long bones, vertebrae, and ribs.

Skeletal infection produces well-demarcated lytic bone lesions with contiguous tissue abscesses (33% of all patients). It most often affects long bones, vertebrae, and ribs.

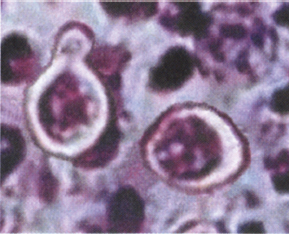

DIAGNOSIS1,23 Clinical suspicion is critical.

• Spherical or budding yeastlike forms may be seen in wet mount or KOH preparation of pus, sputum, secretions, and/or tissue.

Picture courtesy of Danielle Weinstein.

• Gomori methenamine silver stain of tissue specimens.

• Specimens can be cultured on special enriched agar.

• Various immunoassays are available and are sensitive but lack specificity.

TREATMENT1,23 Treat for at least 6 months. The relapse rate is 10–14%, so recheck patients at regular intervals for 1–2 years following completion of treatment.

• Serious non-CNS infection: Amphotericin B 0.3–0.6 mg/kg IV Q day. When patient is stable, switch to itraconazole 200 mg PO Q day.

• CNS infection: Amphotericin B 0.7–1.0 mg/kg IV Q day. When patient is stable, switch to itraconazole 200 mg PO Q day.

• Mild to moderate infection: Itraconazole 200 mg PO Q day or ketoconazole 400 mg PO Q day.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Botulism (Botulinum Toxins)

OVERVIEW Botulism is caused by a group of neurotoxins produced by the obligate anaerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacillus Clostridium botulinum. The botulinum toxins produce their effect by binding to the presynaptic nerve endings at the neuromuscular junctions and prevent the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. They are, by weight, the most toxic substances known, with an LD50 of only .001 μg/kg. Natural intoxication occurs from eating contaminated food. In a bioterrorism attack, botulinum toxins will most likely be released as an aerosol, although they could also be added to the food or water supply. U.S. Army guinea pig studies from the 1940s suggest that botulinum toxins would make a less effective weapon when delivered as an aerosol.

INCUBATION (LATENT) PERIOD The incubation period is normally 18–36 hours after ingestion or inhalation, but it may take up to several days, depending on the size and route of exposure. The incubation period after inhalation may be longer than after ingestion. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE3,5,6 The symptoms of intoxication are identical whether exposure is by ingestion or inhalation.

• Initial presentation consists of bulbar palsies manifested as blurred vision, mydriasis, diplopia, ptosis, photophobia, hoarseness, dysarthric speech, dysphonia, and dysphagia. Patients remain afebrile and may also complain of dry mouth, constipation, and urinary retention.

• Progresses to descending, symmetrical skeletal muscle paralysis in as little as 24 hr following the onset of symptoms. Progressive weakness may produce sudden respiratory arrest and death if untreated.

• Patients remain awake, alert, and oriented throughout the entire illness.

DIAGNOSIS3,5,6 Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation only and must be considered in any cluster of patients with sudden weakness or paralysis without headache or fever. It must be differentiated from other conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (ascending paralysis), shellfish paralysis, tetrodotoxin, tick paralysis, myasthenia gravis, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and atropine poisoning.

• There is an antitoxin that is effective for both food-borne and inhalational intoxication, but it must be given prior to the onset of symptoms or it is ineffective. The antitoxin is derived from horse serum and has the potential for serious hypersensitivity reactions in 7% of recipients. Botulinum antitoxin can be obtained from the CDC (404-639-2206 during business hours, 404-639-2888 at other times).

• Provide supportive care with mechanical ventilation and IV, or enteral nutritional support may be required for months.

• Gastric lavage and activated charcoal may be of benefit immediately following ingestion. Do not give emetic agents such as ipecac.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed). External decontamination is usually not required.

Brucellosis

OVERVIEW Primarily a disease of cattle, goats, and hogs, brucellosis is caused by any of a group of gram-negative coccobacilli called Brucella, but primarily by Brucella suis and melitensis. It is also known as undulant fever. As a weapon, it would most likely be released as an aerosol. Though rarely fatal (less than 5% in untreated patients), its debilitating symptoms and prolonged course would undoubedly put a great burden on the medical infrastructure following a bioterrorist attack with this agent.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Brucellosis has a variable incubation period of 5–60 days. Natural cases are acquired by ingestion of contaminated, unpasteurized dairy products or exposure to body fluids from infected animals. Person-to-person transmission does not occur except by direct exposure to infected body fluids.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,2,3,5

• Initial presentation consists of a flulike illness with symptoms such as intermittent fevers, chills, sweats, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, back pain, generalized weakness, and malaise.

• Cough and pleuritic chest pain may occur in up to 20% of patients.

• GI symptoms occur in up to 70% of patients (mostly adults) and may include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and/or constipation, ileitis, colitis, and infiltrative hepatitis.

• Meningitis occurs in fewer than 5% of cases and may occur acutely at onset or appear later in the course and become chronic.

• Adenopathy, rash, and pharyngitis are more common in children.

• Progresses to lumbar pain and tenderness in 60% of cases due to osteoarticular infections of the spine. Paravertebral abscesses may occur and show up on CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Other joints commonly infected are the sacroiliac joints, hips, ankles, knees, and sternoclavicular joints.

• Endocarditis is rare and is the main cause of death.

• CXR is variable at all stages of the illness and may be normal or demonstrate hilar adenopathy, pleural effusions, single or miliary nodules, abscesses, and/or bronchopneumonia.

DIAGNOSIS1,3,5 Diagnosis is mostly based on clinical suspicion and a history of possible exposure.

• Laboratory and x-ray findings are often normal.

• CBC usually demonstrates a normal white cell count but may show anemia and thrombocytopenia.

• Early diagnosis may be strongly suggested by positive serum agglutinin titer or ELISA.

• Definitive diagnosis can be made during the acute febrile phase by positive cultures of blood (sensitivity of 15–70%) and bone marrow (sensitivity of about 92%).

• PCR may be available from the CDC or local health department.

EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS1,3,5 Treat for 3–6 weeks.

• Doxycycline 100 mg (peds 2.5 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr

• In a suspected large exposure, ADD rifampin 600 mg (peds 10–20 mg/kg) PO Q day.

TREATMENT1,3,5 Treat for 6 weeks.

• Doxycycline 100 mg (peds 2.5 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr PLUS gentamicin 1.0–1.7 mg/kg Q8 hr or 4–7 mg/kg Q day as a single dose (peds: varies by age; see PDR)

• Doxycycline 100 mg (peds 2.5 mg/kg) PO Q12 hr PLUS rifampin 600–900 mg (peds 10–20 mg/kg) PO Q day

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Chikungunya

OVERVIEW Chikungunya is found primarily in Africa and Asia and is caused by an Alphavirus similar to those that cause arthropod-borne viral encephalitis, although chikungunya is not primarily a neurologic illness. The disease it causes consists of a flulike illness with a consistent triad of high fever, rash, and polyarthritis. The clinical illness it produces is difficult to distinguish from other similar Alphaviruses such as Ross River virus, o’nyong-nyong, Sindbis fever, and Mayaro virus. Chikungunya is rarely if ever fatal, making it a relatively poor choice for a weapon, but if released it could produce widespread suffering and disability, overwhelming the medical infrastructure. Aerosol transmission has not been documented, but at least one other Alphavirus (Venezuelan equine encephalitis) is known to spread by this route.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation is 1–12 days (usually 2–3 days). Direct person-to-person transmission has not been documented. Primates and possibly other mammals serve as the natural reservoir. Transmission of the disease is by mosquitoes, which may produce secondary cases following a terrorist attack.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,2,23,27

• Initial presentation:

Abrupt onset of flulike illness with high remitting fever, shaking chills, myalgias, severe headache, retro-orbital pain, photophobia, rash, and often severe arthralgias. Sore throat, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy can also occur in some patients. The acute phase lasts 3–10 days.

Abrupt onset of flulike illness with high remitting fever, shaking chills, myalgias, severe headache, retro-orbital pain, photophobia, rash, and often severe arthralgias. Sore throat, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy can also occur in some patients. The acute phase lasts 3–10 days.

The arthralgias are caused by a polyarticular, migratory, nondestructive arthritis affecting primarily the small joints of the hands, wrists, ankles, and feet. Larger joints are affected to a lesser extent. There may be joint swelling, but effusions are rare. Arthralgias may last for 1 week to several months following infection.

The arthralgias are caused by a polyarticular, migratory, nondestructive arthritis affecting primarily the small joints of the hands, wrists, ankles, and feet. Larger joints are affected to a lesser extent. There may be joint swelling, but effusions are rare. Arthralgias may last for 1 week to several months following infection.

The rash begins as a flushing over the face and trunk, progressing to a maculopapular rash of the trunk and extremities, occasionally including the face, palms, and soles. Pruritis may be present, and young children may additionally develop urticaria. Petechiae may also be noted.

The rash begins as a flushing over the face and trunk, progressing to a maculopapular rash of the trunk and extremities, occasionally including the face, palms, and soles. Pruritis may be present, and young children may additionally develop urticaria. Petechiae may also be noted.

Young children may develop seizures and other neurologic signs.

Young children may develop seizures and other neurologic signs.

A dengue hemorrhagic fever-like syndrome with mild mucosal and GI bleeding may occasionally occur, especially in children.

A dengue hemorrhagic fever-like syndrome with mild mucosal and GI bleeding may occasionally occur, especially in children.

CBC will often show mild leukopenia and a relative lymphocytosis.

CBC will often show mild leukopenia and a relative lymphocytosis.

DIAGNOSIS1,2,23,27 Consider Chikungunya in any cluster of patients with the triad of fever, rash, and arthritis.

• Initiate ELISA for virus-specific IgM antibodies from blood.

• Virus can be recovered from blood during the first 48 hours of illness.

• PCR may become available from the CDC.

• Order rest for arthritic pains, and initiate supportive treatment with IV fluids, whole blood, and management of coagulopathy with platelets, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and vitamin K if necessary.

• NSAIDs may be given for pain. If the arthritis is refractory to NSAIDs, chloroquin phosphate 250 mg Q 24 hr may be helpful in appropriate cases.

• Narcotic analgesics may be given for pain when NSAIDs are not sufficient.

• An untested experimental live-attenuated vaccine exists but would probably not be available.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Cholera

OVERVIEW Cholera is caused by Vibrio cholerae, a free-living, short, curved, motile, gram-negative rod. Although it does not invade the intestinal mucosa, it releases an enterotoxin that produces a severe secretory diarrhea. It can cause a rapid loss of massive amounts of body fluids (up to 1 L/hr), leading to circulatory collapse and death. Cholera frequently causes asymptomatic infection, and in a terrorist attack, it would have to be added to the water supply in huge quantities capable of overcoming chlorination, which normally kills the organism. Both of these factors make it a poor choice for a biological weapon.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation varies from about 4 hours to 5 days (average 2–3 days), depending on the number of ingested organisms. Infection is produced only by ingestion and requires large numbers of organisms, although fewer organisms would be required in patients taking gastric acid suppression therapy. Direct person-to-person transmission has not been documented except by the oral-fecal route.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,2,5 Initial presentation consists of the sudden onset of abdominal cramping, painless watery diarrhea, vomiting, malaise, and headache. Low-grade fever may be present. It progresses to

• Profuse, watery, gray-brown (rice-water) diarrhea. Fluid loss may approach 1 L/hr in about 5% of victims.

• There may be severe muscle cramps, particularly in the calves and thighs, due to water and electrolyte shifts.

• Without treatment, the disease lasts from 1 day to 1 week, with a mortality rate of about 50%. Death is due to massive fluid loss, volume depletion, and circulatory collapse.

DIAGNOSIS1,2,5 The clinical picture is usually diagnostic.

• Stool specimens show no RBCs or WBCs and almost no protein.

• Darkfield or phase contrast microscopy of stool will show highly motile vibrio.

• The organism can be cultured from stool on special media.

• Traditional killed vaccine would be of limited value in a bioterrorist attack due to delayed onset of effect and limited protection.

• Inactivated oral vaccine (WC/rBS) presently available in Europe provides rapid short-term protection.

TREATMENT1,2,5 Treat with antibiotics for 3 days.

• Primary treatment depends on the rapid replacement of lost fluid and electrolytes by oral and/or IV routes. A glucose-electrolyte solution containing 1 L of water plus 20 g of glucose, 3.5 g of NaCl, 2.5 g of sodium bicarbonate and 1.5 g of KCl should be used.

• Ciprofloxacin 1 g (peds 10–15 mg/kg) PO as a single dose or 500 mg (peds 10 mg/kg) PO Q 24 hr for 3 days or

• Doxycycline 300 mg PO for 1 dose or 100 mg PO bid for 3 days

• In suspected or proven tetracycline resistance, consider erythromycin 500 mg (peds 10 mg/kg) PO qid as an additional alternative to doxycycline.

• Alternative pediatric treatment may include TMP (4 mg)-SMX (20 mg) per kg Q 12 hr for 3 days.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Coccidioidomycosis

OVERVIEW Coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) is caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis. This fungus grows naturally in its mycelial form in the soil of the southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and some areas of Central and South America. Human infection occurs via the inhalation of spores (arthroconidia) into the lungs and rarely by cutaneous inoculation with subsequent lymphatic spread. Once within a living host, the spores form spherules, which are the form of the organism that produces tissue infections. Subclinical or mild respiratory infections occur in up to half of all natural infections, but this might differ following a bioterrorist attack because high initial spore exposures have been documented to produce a shorter incubation period and a more severe illness, including diffuse pneumonia with respiratory failure and a septic shock—like syndrome. The mortality rate of coccidioidomycosis is low (1–3%).

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD The incubation period is 7–21 days. Most natural infection occurs by the inhalation of infected dust. Direct person-to-person transmission does not occur.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,23

• Initial presentation:

Consists of fever, dry cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and fatigue. Weight loss, migratory arthralgias, and headache are also common.

Consists of fever, dry cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and fatigue. Weight loss, migratory arthralgias, and headache are also common.

CXR is abnormal in more than 50% of symptomatic patients with unilateral infiltrates, effusions, and hilar adenopathy. Pulmonary nodules and cavitations may be seen occasionally.

CXR is abnormal in more than 50% of symptomatic patients with unilateral infiltrates, effusions, and hilar adenopathy. Pulmonary nodules and cavitations may be seen occasionally.

Rash is common, including an early fine papular, nonpruritic rash that may progress to erythema nodosum and/or erythema multiforme.

Rash is common, including an early fine papular, nonpruritic rash that may progress to erythema nodosum and/or erythema multiforme.

The syndrome of fever, erythema nodosum, and arthralgias (desert rheumatism) should raise a suspicion of coccidioidomycosis.

The syndrome of fever, erythema nodosum, and arthralgias (desert rheumatism) should raise a suspicion of coccidioidomycosis.

• More severe infections may induce a greater than 10% weight loss, severe night sweats of more than 3 weeks’ duration, pulmonary infiltrates involving more than half of one lung, prominent hilar or peritracheal adenopathy on CXR or CT, extreme fatigue with an inability to work, and symptoms for more than 2 months.

• May progress to extrapulmonary dissemination in about 20% of patients, producing

Superficial maculopapular lesions, keratotic and verrucous ulcers, subcutaneous abscesses, and/or lymphadenopathy

Superficial maculopapular lesions, keratotic and verrucous ulcers, subcutaneous abscesses, and/or lymphadenopathy

Joint and bone infections, particularly of the knees, hands, wrists, ankles, feet, pelvis, and vertebrae, which may take 2 years to manifest itself

Joint and bone infections, particularly of the knees, hands, wrists, ankles, feet, pelvis, and vertebrae, which may take 2 years to manifest itself

Coccidioidal meningitis, which is the most severe disseminated form, with a mortality rate greater than 90% within 2 years of diagnosis

Coccidioidal meningitis, which is the most severe disseminated form, with a mortality rate greater than 90% within 2 years of diagnosis

DIAGNOSIS1,23 Clinical suspicion is critical to early diagnosis.

• Identification of C. immitis spherules in sputum or other clinical specimen by culture (5–7 days) or on KOH prep or staining with calcofluor and H and E. Gram staining is not satisfactory to detect spherules.

• Immunodiffusion-tube-precipitin (IDTP) to test for C. immitis–specific IgM (usually positive only during first 2–3 weeks of infection)

• Immunodiffusion-complement-fixation (IDCF) to test for C. immitis–specific IgG (usually positive after the first month)

• ELISA (produces occasional false-positives and requires IDTP or IDCF confirmation)

• PCR (may become available in the future)

• Coccidioides skin test (positive for life, so it might reflect previous infection)

TREATMENT1,23 Treat for 6–9 months depending on the patient’s clinical response. Relapses are common.

• Amphotericin B 0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day IV for 2 weeks (only for the most severe or life-threatening infections), then switch to one of the azoles

• Fluconazole 400 mg PO or IV Q day (for meningitis, give 800 mg Q day for 3 days, then 400 mg Q day)

• Itraconazole 200 mg PO or IV bid

• Voriconazole (probably effective) 200 mg PO or 3–6 mg/kg IV Q 12 hr

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

OVERVIEW Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is caused by a virus of the Bunyaviridae family and produces a viral hemorrhagic fever syndrome. Ruminants and ticks are the primary reservoirs. Asymptomatic and mild infections often occur. Mortality rates are 20–50%. Mortality rates could be higher in an aerosol bioterrorism attack due to a higher initial viral exposure. Any outbreak of hemorrhagic fever in the United States should be highly suspect for a bioterrorism attack.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation is most often about 7–12 days. CCHF is acquired by direct contact with infected animal tissues and body fluids, infected ticks, and by aerosol inhalation. Person-to-person transmission has not been documented. Domestic livestock (primarily ruminants) and arthropods (ticks) are the natural hosts, and natural human infection is accidental.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,22,23

• Initial presentation:

Consists of sudden onset of fever, malaise, generalized weakness, back pain, and asthenia

Consists of sudden onset of fever, malaise, generalized weakness, back pain, and asthenia

The initial phase lasts about 2–7 days and often does not progress beyond this point.

The initial phase lasts about 2–7 days and often does not progress beyond this point.

• May progress to

Fulminant disease with hepatitis, jaundice, DIC, shock, extensive bleeding, and death

Fulminant disease with hepatitis, jaundice, DIC, shock, extensive bleeding, and death

DIAGNOSIS1,22,23 Diagnosis is based mostly on clinical suspicion and a history of possible exposure.

• The differential diagnosis includes typhoid fever, Rift Valley fever, rickettsial infection, leptospirosis, fulminant hepatitis, meningococcemia, and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.

• CBC usually demonstrates thrombocytopenia and leukopenia.

• Proteinuria and/or hematuria are common.

• Virus may be cultured from blood during the acute phase.

• ELISA for virus-specific IgM antibodies from blood or CSF (usually only after 5–14 days of illness)

• Antigen detection by ELISA

• In suspected cases of any hemorrhagic fever, the local department of health or the CDC should be contacted immediately to aid in the definitive diagnosis.

• Caution should be observed in handling specimens due to aerosol risk.

• Supportive treatment with IV fluids and colloids and management of coagulopathy have been successful.

• Ribavirin IV 30 mg/kg loading dose, then 15 mg/kg Q 6 hr for 4 days, then 7.5 mg/kg Q 8 hr for 6 additional days may be helpful.

• Interferon and convalescent human plasma may be helpful.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use contact precautions (gloves, gown, hand washing, and splash precautions).

Dengue Fever (Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever)

OVERVIEW Dengue fever is caused by a virus of the Flavivirus family and produces a viral hemorrhagic fever syndrome with hepatitis, very similar to yellow fever. The attack rate is about 80% of those exposed, but asymptomatic and mild infections are the rule, especially in children. It occurs naturally in South and Central America and often produces cases in the southwestern United States and in Hawaii. Mortality rates are about 1% with good medical care and 20% without. It rarely progresses beyond the prodromal phase, making it a relatively poor choice for a biological weapon.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation is 3–15 days (usually 4–8 days). Direct person-to-person transmission has not been documented, although blood is infectious during the initial phase when viremia is present. Mosquitoes serve as the natural reservoir and vector and may produce secondary cases following a terrorist attack.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,2,5,22,23

• Initial presentation:

Sudden onset of flulike illness with fever, chills, malaise, arthralgias, myalgias, severe frontal headache, retro-orbital pain, generalized flushing, prominent low back pain, and dysesethesia of the skin.

Sudden onset of flulike illness with fever, chills, malaise, arthralgias, myalgias, severe frontal headache, retro-orbital pain, generalized flushing, prominent low back pain, and dysesethesia of the skin.

It may also present with prostration, abdominal tenderness, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, hepatitis, and generalized flushing that progresses to a macular or scarlatiniform rash over 3–4 days (sparing palms and soles).

It may also present with prostration, abdominal tenderness, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, hepatitis, and generalized flushing that progresses to a macular or scarlatiniform rash over 3–4 days (sparing palms and soles).

Even without progression to frank hemorrhagic fever there may be petichiae on extensor surfaces of limbs, GI and mucosal bleeding, and hemoptysis.

Even without progression to frank hemorrhagic fever there may be petichiae on extensor surfaces of limbs, GI and mucosal bleeding, and hemoptysis.

The initial (prodromal) phase lasts 2–7 days.

The initial (prodromal) phase lasts 2–7 days.

• May progress to

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) with hypotension, restlessness, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, diffuse petichiae and ecchymosis, mucosal and GI bleeding, ascites, organomegaly, cyanosis, and sudden shock.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) with hypotension, restlessness, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, diffuse petichiae and ecchymosis, mucosal and GI bleeding, ascites, organomegaly, cyanosis, and sudden shock.

CXR may show pleural effusions and/or ARDS.

CXR may show pleural effusions and/or ARDS.

Laboratory tests usually show thrombocytopenia, ↑ HCT, ↑ LFTs, hypoalbuminemia, and albuminuria and/or hematuria.

Laboratory tests usually show thrombocytopenia, ↑ HCT, ↑ LFTs, hypoalbuminemia, and albuminuria and/or hematuria.

DHF lasts 7–10 days, with a mortality rate up to 80%.

DHF lasts 7–10 days, with a mortality rate up to 80%.

DIAGNOSIS1,2,5,22,23 Diagnosis is based mostly on clinical suspicion and history of possible exposure.

• Virus culture from blood during the acute phase

• ELISA for virus-specific IgM antibodies from blood

• PCR (may be available from the CDC)

• Initiate supportive treatment with IV fluids, whole blood, and management of coagulopathy with platelets, FFP, and vitamin K.

• Use drugs dependent on hepatic metabolism with caution, and avoid the use of aspirin.

• Watch for and treat late secondary bacterial infections.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Domoic Acid (Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning)

OVERVIEW Domoic acid is a heat- and cold-stable, water-soluble tricarboxylic amino acid that is an analogue of glutamic acid. It is naturally produced by the algae Nitzschia pungens. Human intoxication generally occurs by ingestion of shellfish (primarily mussels and clams) that have fed on the algae and concentrated the toxin. Important for its use as a biological weapon is the fact that in addition to GI absorption, it can be absorbed via mucous membranes and by inhalation of an aerosol. Its mechanism of toxicity is presently uncertain, but it may be related to its ability to attach to glutamic acid binding sites and by changes it produces in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Clinically, it produces neurotoxicity that can lead to neuronal death, especially in the temporal lobes and hippocampus.

INCUBATION PERIOD The incubation period is 3–24 hr, depending on the size and route of exposure. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE13,14

• Initial presentation:

Consists of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and severe headache within the first 24 hr following intoxication. Onset may be gradual.

Consists of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and severe headache within the first 24 hr following intoxication. Onset may be gradual.

• Progresses to

Confusion, hyporeflexia, short-term memory loss, disorientation, motor weakness, and mental status varying from agitation to coma.

Confusion, hyporeflexia, short-term memory loss, disorientation, motor weakness, and mental status varying from agitation to coma.

Maximal neurologic deficits peak at about 4 hr following ingestion in mild cases, and at about 72 hr in severe intoxications.

Maximal neurologic deficits peak at about 4 hr following ingestion in mild cases, and at about 72 hr in severe intoxications.

Seizures, profuse respiratory secretions, and cardiac arrhythmias may also be present.

Seizures, profuse respiratory secretions, and cardiac arrhythmias may also be present.

GI absorption of toxin is slow, and the onset and early course following inhalation may be quicker. Improvement may take up to 12 weeks. The risk of permanent neurologic sequelae, such as memory disturbances, increases in victims who develop neurologic symptoms within 48 hr of the initial intoxication.

GI absorption of toxin is slow, and the onset and early course following inhalation may be quicker. Improvement may take up to 12 weeks. The risk of permanent neurologic sequelae, such as memory disturbances, increases in victims who develop neurologic symptoms within 48 hr of the initial intoxication.

DIAGNOSIS13,14 Clinical suspicion is critical.

• Mouse assay with observation for 4 hr. Call your local health department or the CDC if suspicious.

TREATMENT13,14 No specific treatment is available. Give symptomatic and supportive care only. Use diazepam or phenobarbital to control seizures, as phenytoin (Dilantin) may be less effective in this case.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use standard precautions (gloves, hand washing, and splash precautions, as needed).

Ebola and Marburg Viruses

OVERVIEW Both of these viruses of the Filoviridae family produce similar viral hemorrhagic fever syndromes. They are among the most pathogenic viruses known, with mortality rates up to 90% (25–90% depending on viral strain) of all symptomatic cases. Ebola is more common, but little is known about the ecology of either of these viruses. Asymptomatic and mild infections are known to occur, but they are not common. The Russian biowarfare program has weaponized both viruses, and Iraq is also believed to have attempted weaponization. Any outbreak on any continent other than Africa should be highly suspect for a bioterrorism attack.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation for Ebola is 2–21 days (most often about 7 days) and 2–14 days for Marburg. Both are spread by direct contact with infected tissues and body fluids and probably by aerosol inhalation. Person-to-person transmission has been documented, although it is not common. Only 3–10 Marburg virions are sufficient to produce infection.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSEM1,2,5,6,22,23,28

• Initial presentation:

Consists of sudden onset of a flulike illness with fever, chills, headache, myalgia, generalized weakness, prostration, cough, sore throat, and conjunctivitis.

Consists of sudden onset of a flulike illness with fever, chills, headache, myalgia, generalized weakness, prostration, cough, sore throat, and conjunctivitis.

This stage lasts 4–7 days, and the disease often does not progress beyond this point.

This stage lasts 4–7 days, and the disease often does not progress beyond this point.

• May progress to

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, photophobia, maculopapular rash (around day 5), DIC, internal and external hemorrhages, multiorgan failure with jaundice and renal insufficiency, and death.

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, photophobia, maculopapular rash (around day 5), DIC, internal and external hemorrhages, multiorgan failure with jaundice and renal insufficiency, and death.

DIAGNOSI1,2,5,6,22,23,28 Diagnosis is based mostly on clinical suspicion and a history of possible exposure.

• Differential diagnosis includes typhoid fever, rickettsial infection, leptospirosis, fulminant hepatitis, meningococcemia, and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.

• CBC usually demonstrates thrombocytopenia and leukopenia.

• Proteinuria and hematuria are common.

• Virus culture is positive during the acute phase.

• In suspected cases, the local department of health or the CDC should be contacted immediately to aid in the definitive diagnosis.

TREATMENT1,2,5,6,22,23,28 No specific treatment is available. Supportive treatment with IV fluids and colloids and management of coagulopathy with FFP and platelets have been somewhat successful. Convalescent human plasma, if available, may be helpful.

ISOLATION PRECAUTIONS Use airborne precautions (gloves, gown, hand washing, splash precautions, and HEPA or equivalent mask). Maintain strict isolation or cohorting of patients with confirmed infection. Disinfect excreta and other contaminated materials with 10% hypochlorite solution (1 part bleach in 9 parts water).

Encephalitis, Viral (Venezuelan, Eastern, Western, St. Louis, Japanese, and West Nile Virus)

OVERVIEW This category includes the Alphavirus diseases Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE), Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), and Western equine encephalitis (WEE) and the Flaviviruses St. Louis encephalitis (SLE), Japanese encephalitis (JE), and West Nile virus (WNV). All are naturally transmitted by a mosquito vector. Except for VEE, all produce mild or asymptomatic illness in the majority of cases, making them unsuitable weapons. VEE not only produces nearly 100% symptomatic infections with a relatively high percentage of significant neurologic illness, but studies demonstrate that it can be transmitted via the aerosol route and therefore can be effectively weaponized. When released as an aerosol, the number of severe neurologic cases would likely be much higher than in natural occurring cases. VEE has a mortality rate of <1%. Natural human infection usually occurs in summer and early fall and is always preceded by equine cases in the same region. The lack of equine cases and/or an outbreak in winter or spring should suggest a biological weapon attack.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND SPREAD Incubation is 2–6 days. A terrorist attack can be by aerosol release or by release of infected mosquitoes. In any outbreak, local mosquito vectors would become infected, producing a secondary rise in the number of cases. Direct person-to-person transmission via the aerosol route has been suggested but has not been proven.

SYMPTOMS AND CLINICAL COURSE1,2,3,5,23 Nearly 100% of those infected will show some symptoms of overt illness.

• Initial presentation:

Consists of sudden onset of spiking fevers, rigors, malaise, severe headache, photophobia, and myalgias in the low back and legs.

Consists of sudden onset of spiking fevers, rigors, malaise, severe headache, photophobia, and myalgias in the low back and legs.

Nausea, vomiting, sore throat, cough, and diarrhea may quickly follow the initial onset.

Nausea, vomiting, sore throat, cough, and diarrhea may quickly follow the initial onset.

The acute phase lasts 24–72 hr and may progress to full recovery in 1–2 weeks.

The acute phase lasts 24–72 hr and may progress to full recovery in 1–2 weeks.

• May progress to

Severe encephalitis with meningismus, lethargy, somnolence, ataxia, confusion, seizures, paralysis, coma, and death, especially in children.

Severe encephalitis with meningismus, lethargy, somnolence, ataxia, confusion, seizures, paralysis, coma, and death, especially in children.

Mortality following this phase is up to 20%, and many survivors may suffer permanent neurologic sequelae.

Mortality following this phase is up to 20%, and many survivors may suffer permanent neurologic sequelae.

Studies have shown that following an intentional aerosol release, there would likely be a much higher rate of severe encephalitis in both adults and children, with subsequently higher mortality and neurologic sequelae.

Studies have shown that following an intentional aerosol release, there would likely be a much higher rate of severe encephalitis in both adults and children, with subsequently higher mortality and neurologic sequelae.

DIAGNOSIS1,2,3,5,23 Diagnosis is based mostly on clinical suspicion and history of possible exposure.

• CBC often shows a striking leukopenia and lymphopenia.

• Abnormal lumbar puncture with high opening pressure and up to 1000 WBC/mm3 is common.

• Serum can be used for ELISA for VEE-specific IgM, complement fixation, neutralizing antibody, and others.

EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS1,2,3,5,23

• An investigational live, attenuated VEE vaccine is available (TC-83). It requires a single 0.5 cc subcutaneous dose and may produce flulike symptoms in up to 18% of those vaccinated.

• A second investigational inactivated VEE vaccine (C-84) may be used to boost immunity in those who have already received the TC-83 vaccine. It requires a 0.5 cc subcutaneous dose every 2–4 weeks for up to 3 doses, or until an antibody response can be measured.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree