Medical educators must begin teaching tomorrow’s doctors to become much better at creating, improving, and managing processes and systems.

The agonizingly slow flow of patients through a hospital’s units from admission to discharge can cause delays in treatment, medical errors, and poor outcomes. Lean can simplify, streamline, and optimize patient flows for optimal productivity, profitability, and patient outcomes, effectively eliminating the bottlenecks without adding resources.

If you’ve ever been to London and ridden on the famous Underground, you’ve probably seen signs: “Mind the Gap” (Figure 2.1). While the signs are designed to keep travelers from wrenching an ankle, I believe that the idea also applies to Lean thinking.

FIGURE 2.1

Mind the gap.

MIND THE GAP

Here’s what I mean: hold up your hand and spread your fingers wide apart. What do you see? Most likely you’re first drawn to look at your fingers, not the gaps in between them. This is how most people look at process improvement—by looking at the people working, not at the gaps between people.

When you take your eyes off the employees and put your eyes on the patient, product, or service going through the process, you quickly discover that there are huge gaps between one step in the process and the next. You’ll discover work products piling up between steps, which only creates more delay—a bigger gap.

Your turnaround-time problems are in the gaps, not the fingers. You can make your people work faster, but you’ll find that this often makes you slower, not faster, because more work piles up between steps, widening the gap, not narrowing it.

VALUE-STREAM MAPPING AND SPAGHETTI DIAGRAMMING

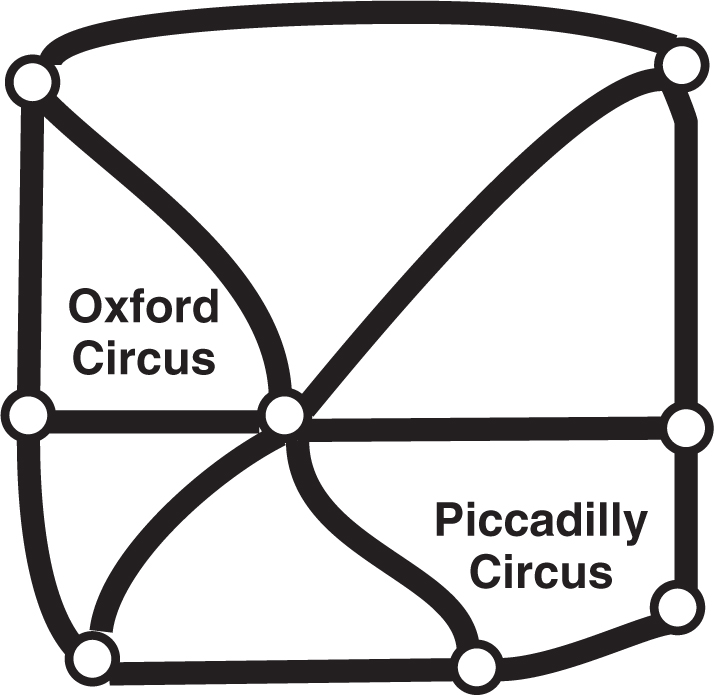

The other sign you often see in the London Underground is a tube map (Figure 2.2). While it is much more interconnected than a typical value-stream map, you’ll notice that the stations are quite small and the lines between them quite long.

FIGURE 2.2

London Underground map.

This is true of most processes: the time between stations is much greater than the time actually spent in the stations. As this map suggests, 95 percent of the time is between stations, not in them. If you want to reduce the time it takes to serve a patient, you have to mind the gaps.

IF THEY CAN DO IT IN BOTSWANA …

At the American Society for Quality World Conference, I talked with two representatives from Botswana. They use the tools of Lean to mind the gap and reduce the response times of the police. They are using the benchmarks of the World Health Organization to improve healthcare response times. If they can do it in Botswana, then you can do it in your hospital.

Most hospitals have a blind spot when it comes to the best way to accelerate their response times. Stop trying to make the clinical and administrative staff faster. Stop trying to keep your people busy when there’s no reason to be busy. Stop doing things patients haven’t asked for yet. Focus on the time between steps.

If you want a faster hospital, mind the gap!

Recently, I took my wife to the Emergency Department (ED) at a local hospital because she was too dizzy to do anything. Here’s the sequence of events:

- I signed her in—and we waited.

- The registration desk had us fill out some paperwork—and we waited.

- The triage nurse took her vital signs and led us to an exam room—and we waited.

- The doctor came in, listened to her symptoms, and ordered some tests—and we waited.

- The phlebotomist took blood samples—and we waited.

- The doctor came back and diagnosed the problem as an inner ear disorder and prescribed meclizine and bed rest.

- Shirley got dressed and we left—two hours after we arrived.

In those two hours, we saw a clinician for perhaps six minutes total. The blood tests that actually take about 10 minutes to process took an hour of elapsed time. In essence, someone was working on diagnosis and treatment for only 18 minutes of the two hours.

Sadly, a typical ED is more like an old-fashioned assembly line, with patients going from processing station to processing station and piling up in between while they wait on the next operator. My 91-year-old mother described her experience of healthcare as “feeling like a can of corn run over a scanner.”

Just like customers in a fast-food restaurant, patients don’t like waiting. According to Press Ganey, the average stay in an ED is over four hours, unchanged for decades. Doctors and nurses have gotten used to this sluggish process and assume that it’s the best they can do. Not so!

THE FAST EAT THE SLOW

How did Robert Wood Johnson’s ED do what others consider impossible? The hospital eliminated the delay between steps. How is this possible, you might ask? There are lots of opportunities:

Why sign in? Why not swipe the magnetic strip on your insurance card, driver’s license, or credit card just like you do at an airport?

Why sign in? Why not swipe the magnetic strip on your insurance card, driver’s license, or credit card just like you do at an airport?

Why have a registration desk when computers on wheels (COWs) can go to patients in an exam room to gather the information necessary while they’re waiting on test results?

Why have a registration desk when computers on wheels (COWs) can go to patients in an exam room to gather the information necessary while they’re waiting on test results?

Why photocopy a patient’s driver’s license and insurance card when lightweight scanners make it easy to do and attach to the patient record.

Why photocopy a patient’s driver’s license and insurance card when lightweight scanners make it easy to do and attach to the patient record.

Why have a triage nurse? I believe that the triage nurse is a bottleneck that slows the response of every ED. Why not have every nurse in a rotation pull the next patient as he or she arrives?

Why have a triage nurse? I believe that the triage nurse is a bottleneck that slows the response of every ED. Why not have every nurse in a rotation pull the next patient as he or she arrives?

Could the doctor gather the patient’s symptoms while the nurse takes the patient’s vital signs? Why does everything have to be done serially rather than in parallel?

Could the doctor gather the patient’s symptoms while the nurse takes the patient’s vital signs? Why does everything have to be done serially rather than in parallel?

Why send samples to the lab? Point-of-care testing is getting cheaper and easier. Moore’s law says that computers double in power and halve in cost every 18 months. Soon the analysis needed will be at a clinician’s fingertips.

Why send samples to the lab? Point-of-care testing is getting cheaper and easier. Moore’s law says that computers double in power and halve in cost every 18 months. Soon the analysis needed will be at a clinician’s fingertips.

Is there a way to expedite admissions? Bed assignment? Of course!

Is there a way to expedite admissions? Bed assignment? Of course!

Can a nursing unit “bid” to take a patient from the ED based on the acuity and nurse-patient ratio in the unit?

Can a nursing unit “bid” to take a patient from the ED based on the acuity and nurse-patient ratio in the unit?

Can the nursing unit transport the patient if the ED is busy?

Can the nursing unit transport the patient if the ED is busy?

Let’s face it, a hospital can’t afford to have patients boarded in the ED. Boarding leads to diversion, which leads to lost revenue:

Value per ambulance: $6,000 or more

Value per ambulance: $6,000 or more

Ambulances per hour: two

Ambulances per hour: two

Heart surgery patients: one out of six ambulances ($100,000+)

Heart surgery patients: one out of six ambulances ($100,000+)

Based on these kinds of numbers (plug in your own), three hours on divert will cost a hospital $130,000 and possibly cost a patient his or her life. While nursing units are trying to maximize their nurse-patient ratios to save a few bucks, the big money is diverted to other hospitals. The chances of diversion increase rapidly when the census (occupancy) exceeds 80 percent.

And what about LWOBSs (patients who leave without being seen)? How many people leave or don’t even enter the ED if the waiting room looks too crowded? Answer: Lots!

The ED is the front door to the hospital, admitting one out of every four patients using the ED. If you really want to be in the patient care business, you will want to get a lot faster than you are.

What are some other examples where speed matters?

Door-to-balloon (D2B) time under 90 minutes for cardiac catheterization patients

Door-to-balloon (D2B) time under 90 minutes for cardiac catheterization patients

Lab turnaround times

Lab turnaround times

Imaging turnaround times

Imaging turnaround times

Discharge turnaround time

Discharge turnaround time

Room cleaning

Room cleaning

Meal delivery

Meal delivery

CORE SCORE

In Marcus Buckingham’s book, The One Thing You Need to Know, there’s a section on knowing your “core score.” What’s the one thing you need to know about your business?

Core Score for Prisons

Buckingham interviewed General Sir David Ramsbotham, who was in charge of Her Majesty’s prisons. He says that he knew he couldn’t make wardens change. In order to make things happen, he had to change the way they measured success:

Old metric: Number of escapees

Old metric: Number of escapees

New metric: Number of repeat offenders

New metric: Number of repeat offenders

The old goal was to keep prisoners in, but the general started thinking, “Who is a prison designed to serve?” Answer: The prisoner! “The main purpose of a prison should be to serve the prisoner. By which I mean that we must do something for the prisoner while he is in prison so that when he is released back into society, he is less likely to commit another crime.” Armed with this new score, he turned the prison world upside-down.

Core Score for Healthcare

In the old world of healthcare, the measure was based on “outcomes”—Did the patient get better no matter how long it took? I am coming to believe that the new world of healthcare is measured on speed.

Door-to-doctor time in the ED of less than 30 minutes

Door-to-doctor time in the ED of less than 30 minutes

ED length of stay (LOS) of under an hour

ED length of stay (LOS) of under an hour

ED-to-nursing floor for admitted patients of under 30 minutes

ED-to-nursing floor for admitted patients of under 30 minutes

LOS of two to three days based on diagnosis

LOS of two to three days based on diagnosis

Discharge-to-disposition (patient transferred) of under 60 minutes

Discharge-to-disposition (patient transferred) of under 60 minutes

Most of these times can run two to four times longer at present. Patients are used to being served in minutes everywhere else. Why not in healthcare? Of course, healthcare will need a few metrics involving patient safety as well.

Most people worry that faster treatment will result in worse outcomes, but if you use Lean correctly, the opposite is true.

SPEED SAVES LIVES

You may remember when the speed limits were lowered nationally to 55 mph to “save lives.” Yet a study by the Cato Institute found just the opposite: The fatality rate on the nation’s roads declined for a 35-year period excluding the period from 1976 to 1980 when the speed limit was 55 mph. After the speed limit was raised in 1995, the fatality rate dropped to the lowest in recorded history. There were also 400,000 fewer injuries.

Furthermore, there’s no evidence that states with higher speed limits had increased deaths. States with speed limits of 65 to 75 mph saw a 12 percent decline in fatalities. States with a 75 mph speed limit saw over a 20 percent decline in fatality rates. Similar improvements are possible in healthcare.

Patient Safety Alerts

Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC) in Seattle is widely regarded for its quest for patient safety and quality. CEO Gary Kaplan offers many insights into the hospital’s journey. It all began in 2001 when the board began to ask, “What is best for our patients?”

As a Lean Six Sigma practitioner, I would say that healthcare normally has asked, “What’s best for our physicians?” and then asked, “What’s best for our patients?” A physician-centric model leads to unnecessary inefficiencies and errors. A patient-centric model changes the way healthcare is delivered.

VMMC began looking for quality leaders and, through Boeing, found the Toyota Production System (TPS)—Toyota’s relentless focus on the customer, quality, and safety—and modeled it to create the Virginia Mason Production System (VMPS). Kaplan says, “When you find and eliminate defects, quality and safety are improved.”

In 2002, VMMC leaders went to Japan to observe Toyota’s production line firsthand. When they observed Toyota’s “stop the line” concept, where any employee can slow or stop the line when he or she notices a defect and everyone rushes to “go and see” what’s going on and fix it, it was a revelation: “If Toyota does this for cars, shouldn’t we be doing this for our patients?”

“In conventional manufacturing, they keep the line going and inspect products afterward. The way it is traditionally done in healthcare is even worse,” Kaplan says. “Two months after the fact, a retrospective quality audit or chart review will be done and find that something should have been done differently—two months ago.”

VMMC created a Patient Safety Alert (PSA) system “Every single staff member is a patient safety inspector and is empowered to stop any process or situation that might cause harm to a patient. To … [2009], we’ve had more than 14,000 PSAs. While it may seem counterintuitive, we think the more PSAs we generate, the safer care is here.” To encourage PSAs and achieve zero defects, VMMC has three key expectations:

It’s safe to report mistakes.

It’s safe to report mistakes.

When mistakes are reported, they will be corrected.

When mistakes are reported, they will be corrected.

Those who report mistakes will be praised.

Those who report mistakes will be praised.

When a PSA is reported, managers and staff use the “five whys” to diagnose and prevent the problem from recurring.

So what’s wrong with the system? Kaplan says that “too many residents and nursing students are still taught that if you try hard enough, you won’t make mistakes. … But we know that’s not true. … humans make on average six errors a day.” Think about it: multiply the daily staffing level by six. How many thousands of errors occur every day? The only choice is to change the system to make those errors impossible.

“The healthcare industry has a defect rate of 3 percent or more,” Kaplan says, “a rate unacceptable in any other industry. Defects can be anything from appointment scheduling errors to wrong-site surgery. Zero is the only acceptable rate for defects. Perfect care must be our goal.”

Cathie Furman, senior vice president of quality and compliance, asked, “What’s the single easiest thing every hospital or clinic could do to make significant strides in patient safety?” Kaplan says, “Listen to staff … and get leaders out of their offices. Genchi Genbutsu means ‘go and see for yourself.’”

Kaplan says, “If we reduce cost by reducing waste, which is what VMPS [Virginia Mason Production System] is all about, we actually improve quality.” Most people find it counterintuitive, but when you speed up the process using Lean, it actually reduces defects by 50 percent or more because there are fewer chances for error.

Could your hospital implement a PSA system that allows every employee, patient, or family member to call an alert that “stops the line” and allows for immediate improvement? It requires

Executive leadership

Executive leadership

Easy, open reporting—“Open the floodgates for all concerns.”

Easy, open reporting—“Open the floodgates for all concerns.”

Rapid change as the organization learns

Rapid change as the organization learns

It took VMMC from 2003 to 2004 to get PSAs up from 125 and 204 a year to 2,450 in 2005 and 3,315 in 2006. It takes time for employees to learn to trust that alerts will be dealt with and improvements incorporated into the system, especially the nurses and nonclinical support personnel, who contribute two-thirds of PSAs.

VMMC also focuses on appropriateness of care. If a patient doesn’t need a procedure or treatment, then, no matter how well it was performed, “There is no quality.” It happens all too often. Robert Kelley estimates that 40 percent of healthcare waste is due to unnecessary care. “Unwarranted treatment to protect against malpractice exposure accounts for $250 billion to $325 billion in annual healthcare spending. Twenty to fifty percent of … [high-tech scans] should never have been done because their results did not help diagnose ailments or treat patients.”

How do you maintain the gains and continue to improve? As Deming would say, “Constancy of purpose at all levels of the organization.” Kaplan says, “The willingness to listen to the voice of the patient is what keeps us moving forward.”

YOU ALREADY UNDERSTAND LEAN

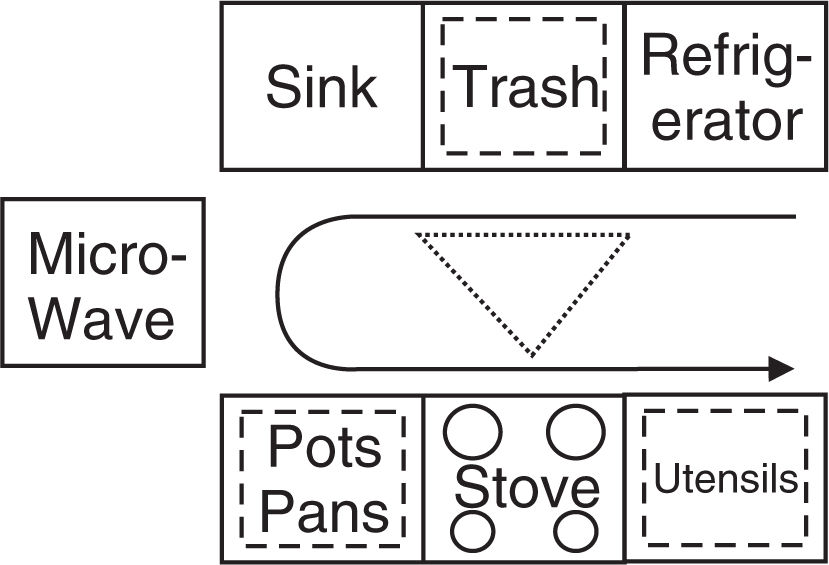

I’d like to suggest that you already have been exposed to and understand the concepts behind Lean. Kitchens, for example, have long been designed as “lean cells” for food preparation. The refrigerator, sink, and stove should form a V-shaped work cell. The tighter the V, the less movement is required of the cook. My kitchen looks like Figure 2.3. Food comes out of the refrigerator, gets washed in the sink, cut up on the counter, cooked on the stove, and delivered to the dining table in a neighboring room. Unlike mass production, where different silos would be put in charge of frozen and refrigerated food, washing, cutting, and cooking, there’s usually only one cook who handles each of these steps. Each meal is a small “batch” or “lot.” You never cook in batches big enough for the entire week. A trip to the supermarket each week replenishes the limited inventories of raw materials required. Ever noticed how most kitchens are right off the garage? In this way, each week’s groceries come straight out of the garage right into the kitchen with a minimum of movement. Your kitchen is the essence of a Lean production cell.

FIGURE 2.3

Lean kitchen layout.

How can you set up your workplace (ED, operating room, lab, radiology suite, nursing unit, intensive care unit, administration) to use the insights gleaned from your kitchen?

THE POWER LAWS OF SPEED

It’s not the big that eat the small, it’s the fast that eat the slow.

The amount of time it takes to deliver a product or service is far greater than the actual time spent adding value to the product or service. Most patients, products, and services are worked on for only three minutes of every hour of the total elapsed time (value-added). Why does it take so long? Delay. The patient, product, or service is sitting idle for far too long between steps in the process (non-value-added).

Being busy is a form of laziness—lazy thinking and indiscriminate action.

The 3-57 Rule: Your employees are busy, but they are only working with each patient for three minutes out of every hour. Your patient is waiting for 57 minutes of every hour. Watch your patient, product, or service, not your physicians, nurses, or technicians.

The 15-2-20 Rule: Every time you reduce the time required to provide a product or service by 15 minutes per hour, you double productivity and cut costs by 20 percent. It has been my experience that you can reduce cycle and turnaround times by 30 to 50 minutes per hour so that your productivity increases, and cost reductions and profit margin improvement should far exceed the 15-2-20 rule.

The 3 × 2 Rule: When you slash your cycle time for your mission-critical processes (door to doctor, door to test, or door to balloon), you enjoy growth rates three times the industry average and twice the profit margins. This is a good thing because most companies find that they need only about two-thirds of the people to run the business after applying Lean, but if you’re going to grow three times faster than the industry, you’re going to need all those employees to meet the demand.

ECONOMIES OF SPEED

There is always a best way of doing anything.

One of the best ways to improve a process is to find and eliminate as much of the delay as possible. Although the people are busy, the customer’s order is idle up to 95 percent of the time—sitting in queue, waiting for the next worker. Delays occur in three main ways:

Delays between steps in a process

Delays between steps in a process

Delays caused by waste and rework

Delays caused by waste and rework

Delays caused by large batch sizes (The last item in the batch has to finish before the first item can go on to the next step. This is not a common problem in healthcare.)

Delays caused by large batch sizes (The last item in the batch has to finish before the first item can go on to the next step. This is not a common problem in healthcare.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree