CHAPTER 2 Formulating for the Individual Patient

A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH

The Western herbal system of prescribing for the individual patient is simpler than that for traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine and does not necessarily require traditional diagnostic techniques such as the pulse and tongue. Nevertheless, the Western system can be powerful, and the author of this text has seen the Western herbal prescription succeed when other approaches have failed. The systematics of the Western herbal approach are summarized here. For a full exposition on this topic, the reader is referred elsewhere.1

The goals of Western herbal prescribing for the individual patient are to:

Information about the causes of a patient’s health problems can come from several sources:

HOW TO PREPARE A FORMULATION ACCORDING TO WEEKLY DOSES

If the patient is to take 5 ml of a formulation three times a day (15 ml per day), the total amounts to 105 ml per week, which can be rounded down to 100 ml. The herbs in the formulation can then be assigned appropriate doses by referring to their weekly dose ranges in the dosage table provided in Appendix A or in the individual monographs. The total should add up to 100 ml. The patient is then advised to take 5 ml three times per day, thereby automatically receiving the required amount of each herb.

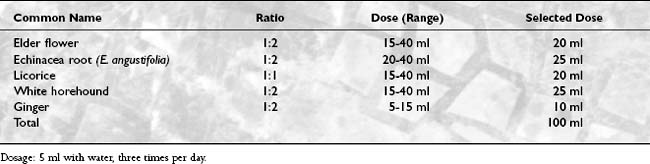

An example prescription for 1 week might be similar to that shown in Table 2-1.

In this example, the herbs were selected, and then the appropriate dose of each herb was chosen by considering the weekly dose range in conjunction with the purpose of the herb in the formula. Each of the herbs selected falls within its dose range, and the total also adds up to 100 ml. If the total turns out to be greater than 100 ml, then the formula would normally be adjusted (by lowering the dose of individual herb or herbs—but not below the minimum in the dose range—or by reducing the number of herbs or by substituting an herb that has a lower dose range). Alternatively, the total might be adjusted to 105 or 110 ml without compromising the doses of individual herbs.

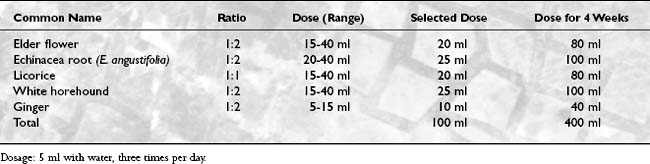

The previous sample prescription provides enough formula for 1 week. When dispensing for more than 1 week, the weekly doses are multiplied by the number of weeks required. For example, see Table 2-2.

THERAPEUTICS

ACUTE BRONCHITIS

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs

Example Formula.

| Echinacea root (E. angustifolia or E. purpurea) | 1:2 | 25 ml |

| Pleurisy root | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Ginger | 1:2 | 5 ml |

| Elecampane | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Licorice | 1:1 | 15 ml |

| Fennel | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Total | 105 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with 40 ml warm water five to six times a day.

ALLERGIC RHINITIS

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs.

The goals of herbal treatment include the following:

Example Formula.

| Echinacea root (E. angustifolia or E. purpurea) | 1:2 | 35 ml |

| Eyebright | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Golden seal | 1:3 | 20 ml |

| Baical skullcap | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Total | 105 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with water three times a day before meals.

ANXIETY

Background.

Anxiety disorders can be classified as follows:

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs

Example Formula.

| Valerian | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Passion flower | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Ashwaganda | 1:2 | 35 ml |

| St. John’s wort | 1:2 | 25 ml |

| Total | 100 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with water three times a day.

ASTHMA

Background.

Asthma has been defined as the occurrence of dyspneic bronchospasmodic crises that are linked to a bronchial hyperreactivity (BH).2 Similar to autoimmune disease, asthma is a chronic disturbance of immunologic function, which can be controlled to some extent but not eradicated by modern drug therapy. In other words, asthma is not just the attacks (crises). Asthma is a chronic disturbance of the immune system. The attacks are the “tip of the iceberg.” Hence any treatment aimed only at relaxing airways and relieving symptoms, be it orthodox or herbal, is superficial and will not change the chronicity of the disease.

Recent research has identified many factors that may contribute to the causes and morbidity of asthma. Traditional herbal medicine also recognizes the role of inefficient digestion, poor immunity, stress, inadequate diet, and unhealthy mucous membranes in the development of the disease. Contributing factors identified from research on patients with asthma include inhaled allergens (exposure to which contributes to the chronicity of the disease, not just the attacks), dietary allergens, poor air quality, concurrent sinusitis,3,4 poor hydrochloric acid production,5 gastroesophageal reflux (GER),6,7 coexisting or episodic infections,8–10 excessive salt intake,11 poor immunity,12,13 stress,14,15 and antioxidant status.16–18 Platelet-activating factor (PAF) may be involved in the inflammatory response. (Ginkgo has anti-PAF activity.)

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs.

Tables 2-6 and 2-7 outline the treatment strategy for asthma.

TABLE 2-6 Treating the Underlying Factors That Created the Asthmatic Condition

| Goal | Required Actions | Herbs |

|---|---|---|

| Control the allergic response | Antiallergic | Baical skullcap, Albizia |

| Treat sinusitis | Anticatarrhal, antiallergic, immune enhancing | Eyebright, Andrographis |

| Increase gastric acid | Bitter tonic, digestive | Gentian, Andrographis |

| Control reflux | Antispasmodic, demulcent, antacid, mucoprotective | Meadowsweet, marshmallow root, licorice |

| Eliminate infection | Immune enhancing, antiviral, antibacterial | Echinacea root, Andrographis |

| Reduce the physical effects of stress | Adaptogen | Astragalus, Eleutherococcus |

| Reduce anxiety and tension | Sedative and nervine tonic | Valerian, St. John’s wort |

| Boost the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis | Tonic, adrenal tonic | Ashwaganda, Rehmannia |

| Balance immunity | Immune modifying, immune depressant | Echinacea root, Hemidesmus, Tylophora |

| Improve antioxidant status | Antioxidant | Ginkgo, rosemary |

| Improve the health of mucous membranes | Anticatarrhal, mucous membrane trophorestorative, lymphatic, depurative | Eyebright, golden seal |

TABLE 2-7 Treating the Symptoms and Sustaining Causes of Asthma, Such as Inflammation

| Goal | Required Actions | Herbs |

|---|---|---|

| Control the allergic response | Antiallergic | Baical skullcap, Albizia |

| Control acute respiratory infection | Diaphoretic, immune enhancing | See information for common cold and influenza |

| Reduce inflammation | Antiinflammatory, reflex demulcent | Ginkgo, Bupleurum, marshmallow root |

| Clear the airways | Expectorant | Elecampane, fennel |

| Relax bronchial smooth muscle | Bronchospasmolytic | Elecampane, Grindelia, Coleus |

| Allay debilitating cough | Expectorant, demulcent, antitussive | Elecampane, marshmallow root, Bupleurum, licorice |

Example Formulas

| Baical skullcap | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Ginkgo (standardized extract) | 2:1 | 25 ml |

| Eyebright | 1:2 | 15 ml |

| Echinacea root blend | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Total | 100 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with water three to four times a day.

| Licorice | 1:1 | 15 ml |

| Meadowsweet | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Marshmallow root glycetract | 1:5 | 65 ml |

| Total | 100 ml |

Dosage: 3 to 5 ml undiluted as required up to six times a day.

| Astragalus | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Valerian | 1:2 | 15 ml |

| Rehmannia | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Ashwaganda | 1:2 | 35 ml |

| Total | 110 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with water three to four times a day.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

Background.

The ultimate effect is increased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) within the prostate. New generation drugs for BPH such as Proscar (finasteride) inhibit the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase, which converts testosterone into DHT.

A dynamic component to the symptoms of urethral obstruction is also present, which is known as “prostatism.”19 Alpha-adrenergic (sympathetic) nerve fibers innervate the smooth muscle of the prostatic urethra and bladder neck. Some of the symptoms of BPH are related to the state of contraction of this smooth muscle, which explains why symptoms can vary in severity at any given time for a man with BPH. Alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs such as Minipress (prazosin hydrochloride) are often prescribed to alleviate the symptoms of prostatism.

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs

Example Formula.

| Saw palmetto | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Nettle root | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Crataeva | 1:2 | 40 ml |

| Total | 100 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with water three times a day.

CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

Background20.

Patients with CFS were usually devitalized before they contracted the disorder. This condition might have been the result of emotional pressures, work pressures, family pressures, ambition, toxins, pregnancy, or even a bad diet; but the end result is the same. The finding that stress is a significant predisposing factor in CFS supports this observation.21 Any stressor, be it chemical, physical, biologic, or emotional, then acts to aggravate the condition. This reduced capacity to cope with stress is a key factor in creating the vicious cycle, which perpetuates the syndrome.

Possible factors identified in the cause or progression of CFS include viruses, immune abnormalities, circulatory abnormalities (including reduced blood flow to some parts of the brain), brain abnormalities, pituitary abnormalities, and sleep disorders, as well as muscle, metabolic, and biochemical abnormalities.20 Depression is a common feature that is to be expected given the morbidity of this disorder and its association with poor vitality.

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs

Example Formula.

| Korean ginseng | 1:2 | 10 ml |

| Ashwaganda | 1:2 | 35 ml |

| St. John’s wort (high hypericin) | 1:2 | 15 ml |

| Ginkgo (standardized extract) | 2:1 | 20 ml |

| Astragalus | 1:2 | 30 ml |

| Total | 110 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with water three times a day.

COMMON COLD AND INFLUENZA

Background.

In contrast, influenza is often a more severe respiratory infection that can result in loss of life. The main viruses that cause influenza are enveloped viruses known as influenza A and B.22 These viruses are capable of mutating, and new strains constantly appear. Influenza is also mainly a winter disease. The influenza virus can produce a range of disease states, from a mild common cold to fatal pneumonia (especially in older adults or people who are severely debilitated). True influenza is usually differentiated from other “flulike” illnesses by its marked systemic symptoms, with high fever, malaise, and muscle pain. Bed rest is usually always required.

Treatment Strategy: Goals, Actions, and Herbs

Example Formula.

| Echinacea root (E. angustifolia or E. purpurea) | 1:2 | 35 ml |

| Ginger | 1:2 | 5 ml |

| Lime flowers | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Eyebright | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Elder flower | 1:2 | 20 ml |

| Total | 100 ml |

Dosage: 5 ml with 40 ml hot water five to six times a day.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree