CHAPTER 19. LUMBAR PUNCTURE

Indications155

Contraindications156

Equipment156

Structures through which the spinal needle passes158

Practical procedure158

Post-procedure investigations163

Complications164

Suggested reading164

In 1885 the American neurologist James Leonard Corning (1855–1923) performed a lumbar puncture on a dog and injected cocaine in what proved to be the first demonstration of spinal anaesthesia. Heinrick Quincke (1842–1922) of Quincke’s sign fame (capillary nailbed pulsation of aortic regurgitation) reported a lumbar puncture performed in 1888 for hydrocephalus-associated headaches 1 month before Walter Essex Wynter’s (1860–1945) publication in the Lancet in 1889. Wynter described four cases of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) aspiration in children with TB meningitis at the Middlesex Hospital, London which he performed by cut down to dura at L2 and placement of Southey’s tubes for drainage.

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar puncture in the ward-based setting is usually performed in order to obtain CSF for investigation of neuroaxial conditions. Lumbar puncture is also commonly undertaken in order to provide spinal anaesthesia for operative procedures on the lower abdomen and lower limbs. Additionally lumbar puncture may be used for delivering intrathecal chemotherapy. However, these latter two situations are outside the remit of this chapter.

INDICATIONS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

• Coagulopathy (recent aspirin, heparin last 12 hours, international normalized ratio above 1.2, activated partial thromboplastin time ratio above 1.2).

• Local sepsis over puncture site.

• Raised intracranial pressure (see Tip Box).

• Cardiorespiratory compromise.

• Suspected spinal cord mass or intracranial lesion (see Tip Box).

• Spinal cord compression.

• Lack of consent.

• Spinal cord deformities are a relative contraindication depending upon the spinal anatomy and the experience of the operator (e.g. scoliosis). If you are unsure of the anatomy, consult a senior colleague.

Tip Box

Tip BoxWhen to perform a head CT prior to lumbar puncture:

• >60 years of age.

• Symptoms or signs of raised intracranial pressure (persistent vomiting, history of recent seizure(s), reduced Glasgow coma scale, papilloedema).

• Focal abnormal neurology on examination.

• Immunocompromised (e.g. HIV positive).

• Recent head injury.

• When a possible intracranial bleed is the preliminary diagnosis (in which case a negative computerized tomography of the head should precede subsequent lumbar puncture).

EQUIPMENT

Tip Box

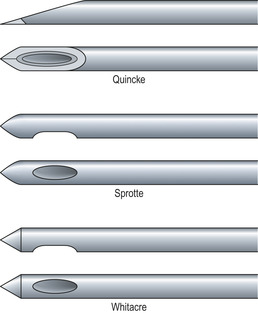

Tip BoxLumbar puncture needles are divided into two types: ‘atraumatic’ needles (e.g. Sprotte or Whitacre) and typical ‘cutting’ needles (Quincke) (Fig. 19.1).

|

| Fig. 19.1 |

The ‘non-cutting’ tip of atraumatic needles is designed to part the dural fibres rather than shear them, and so upon removal of the needle from the dura a smaller hole remains than with a cutting needle. This reduces the amount of CSF loss post-lumbar puncture, and several randomized double-blind studies have been published showing that post-lumbar puncture headaches are reduced ten-fold when using atraumatic needles.

Given their non-cutting tip design, atraumatic needles do not puncture the skin as freely as a typical Quincke needle. They require an introducer needle to puncture the skin, through which the atraumatic needle is passed. If you go on to use atraumatic needles, familiarize yourself with the apparatus prior to use.

STRUCTURES THROUGH WHICH THE SPINAL NEEDLE PASSES

The lumbar puncture needle passes through the following tissues in sequence to reach the subarachnoid space (Fig. 19.2): skin, subcutaneous tissue, the supraspinal ligament, the interspinal ligament, the ligamentum flavum, the dura mater and finally the arachnoid mater.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree