Pediatric Surgery

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter the reader will be able to:

• Identify diagnostic methods used in pediatric patients

• Identify specific instrumentation and supplies applicable to pediatric surgery

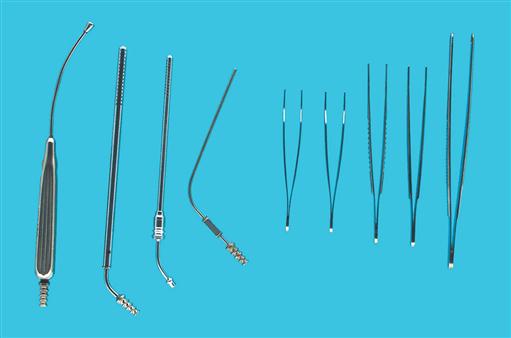

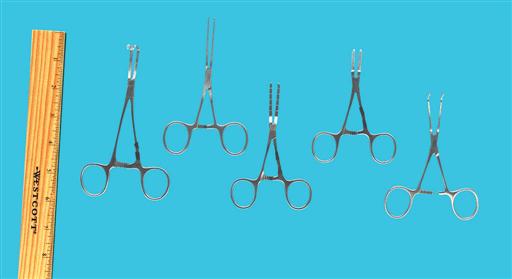

• Identify instruments and equipment used in open, laparoscopic, and endoscopic procedures

Overview

Pediatrics is a specialty focused on the health and well-being of neonates, infants, children, and adolescents. The pediatric patient often needs surgery for congenital anomalies that threaten life or the child’s ability to function. Trauma also impacts a child’s health far more often than an adult’s; injury is a common reason for surgical intervention. Pediatric surgery is an area of practice unto its own because the pediatric patient is so very different from an adult. The field is even further subdivided into all the surgical specialties. It is important to recognize that the difference between pediatric care and adult care is not just a size issue; from birth onward, the body and organs exist in a continual state of development, and multiple physiologic changes occur with age. Major areas of distinction are the airway and pulmonary status, cardiovascular status, temperature regulation, metabolism, fluid management, and psychologic development. A thorough knowledge of these differences is integral to the provision of nursing care for the pediatric patient in the OR.

Advances in surgical interventions for children have been phenomenal in the last two decades for many reasons. The advancement of improved diagnostic and interventional technology, the development of new anesthetics and pharmacologic agents for pain management, and the creation of even smaller and more delicate instrumentation have revolutionized perioperative care of the pediatric population. Numerous pediatric surgeries that were once performed as open cavity procedures are now being done endoscopically with minimally invasive techniques, resulting in shorter hospital stays and faster recovery times. Improvements in the transport of critically ill children and the intensive care management of neonatal and pediatric patients as well as the development of new surgical procedures are also saving more lives yet presenting medical professionals with a new and unique set of problems as complex, medically fragile children are now surviving into adulthood.

Pediatric Surgical Anatomy

Airway/Pulmonary Status

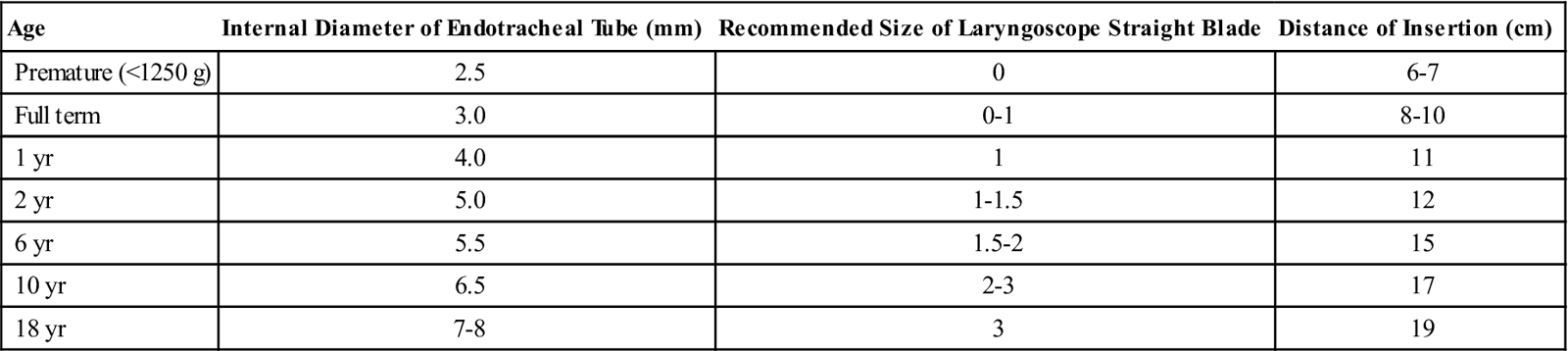

Respiratory mechanics alter dramatically from infancy to adulthood, resulting from increases in airway size, transformations in the rigidity of airway and chest structures, and major changes in neuromuscular status. A proportionally large head, a short neck, and a large tongue in relation to jaw size create more of a challenge for airway management. The glottis is very anterior, moving from the level of the second cervical vertebra to the level of the third to fourth vertebrae in the adult. The epiglottis is floppy and more curved, and the vocal cords are slanted anteriorly. The airway forms an inverse cone with the narrowest portion at the cricoid cartilage until 8 years of age; endotracheal tube size is therefore very important, since a tube that passes easily through the glottis may be too tight at the subglottic area, compromising the child’s airway in the immediate postoperative period because of swelling. The infant is an obligate nasal breather, and the chest wall of an infant is very compliant, leading to increased work of breathing with any type of airway compromise. Infants also have type 2 respiratory muscle fibers until age 2 years, which fatigue more easily than type 1 muscle fibers. Premature infants are at risk for postanesthetic apnea until 60 weeks after conception age. There is a depression in the CO2 response curve in infants; compared to an adult, the respiratory rate does not increase as readily in response to a rising CO2 level, although all ages undergo a CO2 response depression related to inhalational agents and narcotics. One of the most important considerations is that children have a much smaller pulmonary functional residual capacity; a child becomes hypoxic more quickly if the airway is lost. Alveolar maturation is not complete until 8 years of age. Smaller airways have higher resistance; airway resistance decreases approximately 15 times from infancy to adulthood, again with a major change occurring around 8 years of age. It is important to note that smaller airways can become compromised with even a minor amount of swelling. Be aware that loose teeth are common in children aged 5 to 14 years; a dislodged tooth is a potential airway foreign-body risk.

Cardiovascular Status

The most dramatic changes in the cardiovascular system occur at birth with the transition from fetal circulation. Even in full-term infants, persistent transitional circulation may occur. Heart rate is the predominant determinant of cardiac output in infants and children; bradycardia drastically decreases cardiac output and requires swift intervention. There is a decreased cardiac compliance because of a lower proportion of muscle to connective tissue until age 1 to 2 years, making infants preload insensitive. Young children are predisposed to parasympathetic hypertonia (increased vagal tone), which can be induced by painful stimuli such as laryngoscopy, intubation, eye surgery, or abdominal retraction. Attention to blood loss in young patients is very important because the patient’s total blood volume is very small. Blood volume in neonates is 80 to 90 ml/kg; at 1 to 6 years it is 70 to 75 ml/kg; and at age 6 years to adult it is 65 to 70 ml/kg. At birth, 70% to 90% of the hemoglobin is fetal hemoglobin with a high affinity for oxygen. It is normal for hemoglobin levels to fall at about 2 to 3 months of age (physiologic anemia) to a hematocrit level of 29% and a hemoglobin level of 10 mg/dl as the infant’s body begins to produce its own blood cells. A cardiology evaluation is essential if a murmur is auscultated. A murmur can be from a patent foramen ovale, which normally closes at 3 to 12 months; a patent ductus arteriosus, which can be present for up to 2 months; a previously undetected cardiac anomaly; or an innocent flow murmur. The evaluation is critical because anesthetic agents cause vasodilation and potentiate cardiac dysrhythmias.

Temperature Regulation

Infants and young children are most at risk of hypothermia because of their increased body surface area/weight ratio and thin fat layer. Cold stress leads to increased oxygen consumption, resulting in hypoxia, respiratory depression, acidosis, hypoglycemia, and pulmonary vasoconstriction. Hypothermia alters drug metabolism, prolongs the action of neuromuscular blockers, and delays emergence from anesthesia. The child’s temperature must be monitored continuously throughout the intraoperative experience. An axillary temperature probe is acceptable for short procedures in healthy children; an esophageal or rectal temperature probe provides more accurate monitoring of the child’s temperature for longer procedures. Hyperthermia should also be avoided, because it leads to increased oxygen consumption and increased fluid losses.

It is vital to maintain normothermia in children, and the easiest way to do this is by exposing only the area on which surgery is being performed. Additional thermoregulatory interventions include altering the room temperature before the child enters the room, using a water-filled temperature-regulating blanket under the patient, or using a forced-air warming blanket over nonsurgical areas of the child. An overhead heater can be used during the anesthetic induction and patient preparation period immediately before prepping and draping. The anesthesia ventilation circuit can be heated and humidified, as can insufflated carbon dioxide during minimally invasive surgical procedures. For surgical procedures with large areas of exposure, warmed solutions should be available for use instead of room temperature solutions. Intravenous (IV) solutions can also be warmed before administration.

Metabolism

Infants have a higher basal metabolic rate than adults, and it is greatest at 18 months. Most importantly, children younger than age 2 years have immature liver function; pharmacologic response is altered, and there is slower hepatic clearance, decreased hepatic enzyme function, and decreased protein binding. Drug distribution is different in neonates and infants compared with older children and adults because of an increased percentage of total body weight and extracellular body fluid. Infants have an immature blood-brain barrier and decreased protein binding, which results in an increased sensitivity to sedatives, opioids, and hypnotics.

Fluid Management

Renal function at birth is immature, and the ability of the kidneys to concentrate urine is limited, so the infant is much more prone to dehydration. Complete maturation of renal function occurs at about 2 years. Compared to an adult, a child has a higher body water weight, a higher body surface area, and an increased metabolic rate, resulting in increased fluid requirements per kilogram of body weight. Despite these significant points, it is also important to remember that the body weight of the child, the length of time without fluids, and surgical losses are the primary factors in the calculations of the child’s hydration needs.

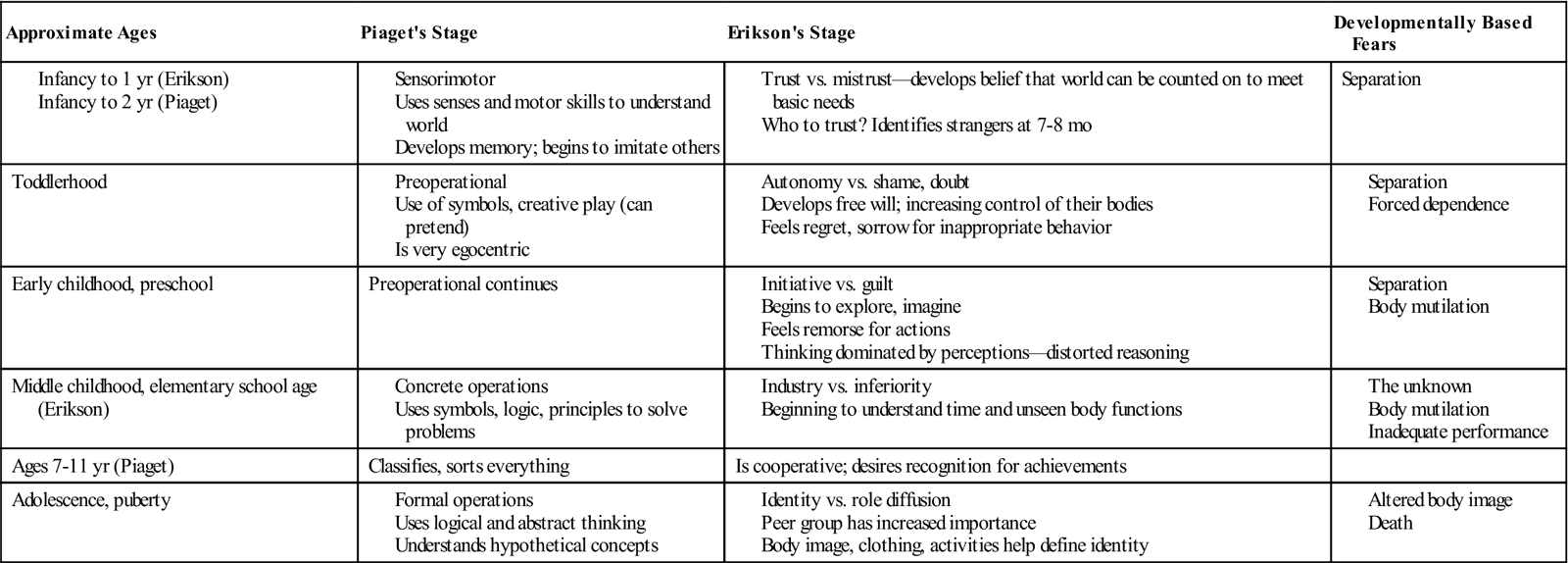

PSYCHOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT

A child’s comprehension of and responses to the environment are based on his or her developmental age. A key factor is that a child’s developmental age does not necessarily match the chronologic age. Patient care should be tailored to the developmental age of the child to optimize the child’s ability to understand the situation, to minimize the child’s and family’s stress and anxiety, and to facilitate the development of a trusting and supportive medical relationship. The types of fears are also related to the child’s level of psychologic development. Predictable stages mean predictable behaviors. The stages of growth have been described from a variety of different aspects; Dr. Jean Piaget described the stages by changes in cognition and the ability to think, and Dr. Erik Erikson based the stages on psychosocial and emotional needs. Their work provides an excellent guideline for assessing the pediatric patient’s developmental level in order to use appropriate interventions (Table 17-1).

TABLE 17-1

Modified from Taylor E: Providing developmentally based care for toddlers, AORN J 87(5):992-999, 2008; Taylor E: Providing developmentally based care for school-aged and adolescent patients, AORN J 90(2):261-269, 2009; Stages of social-emotional development in children, available at www.childdevelopmentinfo.com/development. Accessed August 23, 2009.

Surgical Technologist Considerations

The initial patient assessment provides information necessary to develop a plan of care specific to the needs of each particular pediatric patient related to age, developmental level, and diagnosis. The unique aspects of care of the pediatric surgical patient revolve around the fact that the child is constantly growing and changing.

Anticipating that pediatric patients will have anxiety about leaving their parents, the surgical technologist may need to be available to help the circulator when the patient is brought into the OR. The surgical technologist will need to have equipment, supplies, and instrumentation specific to the scheduled specific surgical procedure or unscheduled surgical procedure in pediatric surgery. It is also important to know the age and weight of the child. This information will guide selection of the correct instruments, supplies, and solutions used.

Pediatric patients differ dramatically from adult patients; therefore, the surgical technologist will need to anticipate the possible need for changes in instrumentation and sponge sizes as well as the temperature of irrigations and solutions. In some instances, the pediatric patient will have had several procedures, and this can lead to longer procedure time and the need for additional specialty instruments and supplies because of the buildup of scar tissue and adhesions. There may be a need for warming lights in addition to the heating blanket used to keep the child’s temperature stable.

Multiple procedures may be done simultaneously on the pediatric patient. The surgical technologist will need to be prepared to have more than one sterile operative setup, or break down and re-restablish the operative field several times. As with any surgical procedure, the principles of aseptic technique must be adhered to diligently. The pediatric patient with either congenital condition or traumatic injury is susceptible to infections.

When involved with pediatric surgery, it is imperative for the surgical technologist to have knowledge of the procedure being performed and the equipment to be used. Keeping current on the latest advancements in pediatric surgery will help ensure the most positive outcome for the patient.

Informed Consent.

Informed consent from the parent or legal guardian of the pediatric patient is required unless the patient is an emancipated minor. An emancipated minor is one who is legally under the age of consent but is recognized as having the legal capacity to consent. Minors may become emancipated by pregnancy, marriage, high school graduation, independent living, and military service. It is important for children to develop a trusting relationship with medical professionals and that these older children are in agreement (within their developmental capabilities) with their family’s decision regarding surgery.

Child Abuse and Neglect.

The surgical team is obligated to screen all pediatric patients for abuse or neglect. Child abuse and neglect are defined as “physical or mental injury, sexual abuse or exploitation, negligent treatment or maltreatment” (Betz and Sowden, 2008). Child abuse is found in all segments of society, crossing cultural, ethnic, religious, socioeconomic, and professional groups. The surgical team is in a unique situation to assess for the presence of abuse because the patient will be disrobed in the OR. Box 17-1 lists the clinical manifestations of child abuse. Every state has a child abuse law that dictates legal responsibility for reporting abuse and suspicion of abuse, and all healthcare providers are mandated reporters. Failure to report suspected child abuse could result in a fine or other punishment, according to individual statutes (Betz and Sowden, 2008).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access