14 CASE 14

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF KEY SYMPTOMS

Arterial blood pressure is determined by the volume of blood in the arterial system and the arterial compliance. Volume of blood in the arteries reflects the inflow from the cardiac output and the outflow, determined by total peripheral resistance (see Fig. II-2)

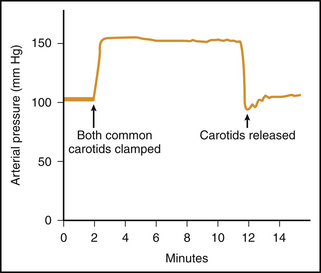

Acute alterations in arterial blood pressure are buffered by the arterial baroreceptor reflex. When blood pressure in the carotid sinus or aortic arch falls there is a reflex activation of the sympathetic nervous system and inhibition of the parasympathetic nervous system. The resultant increases in heart rate, ventricular contractility, arteriolar constriction, and venous constriction all act to restore blood pressure back toward normal (Fig. 14-1).

Chronic hypertension results in a hypertrophy of the left ventricle. This hypertrophy can be evident on cardiac imaging or can be manifested by a left axis deviation of the electrocardiogram. The ventricular hypertrophy results from the increased work load imposed on the left ventricle due to the elevated afterload (arterial pressure). This ventricular remodeling occurs only after many months of persistent hypertension (Fig. 14-2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree