Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter the reader will be able to:

• Indicate the primary reasons for plastic and reconstructive surgery

• Describe the surgical anatomy and physiology associated with the integumentary system

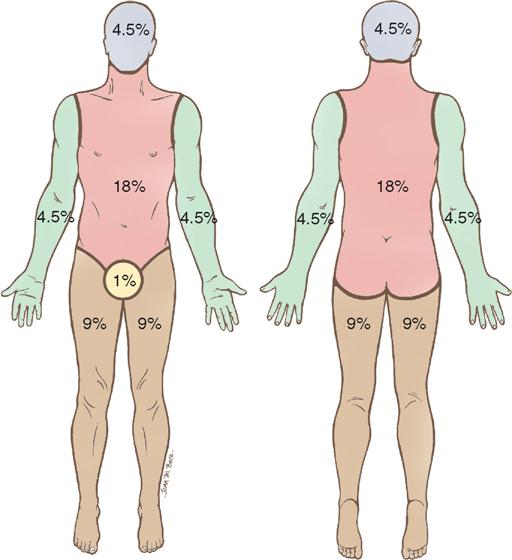

• Recognize the special considerations for burns

• Identify grafts, implants, and prostheses relevant to plastic and reconstructive surgery

• Summarize the surgical technologist considerations related to plastic and reconstructive surgery

• Discuss the procedural steps involved in plastic and reconstructive surgery

Overview

Derived from the Greek word plastikos, which means to mold or give form, plastic surgery is a medical specialty that restores or gives shape to the body. There are two different subspecialties of plastic surgery. Cosmetic surgery restores or reshapes normal structures of the body, to improve appearance and self-esteem. Reconstructive surgery treats abnormal structures of the body caused by birth defects, developmental problems, disease, tumors, infection, or injury to restore function and correct disfigurement or scarring (American Society of Plastic Surgeons [ASPS], 2009a.) As a surgical specialty, plastic surgery owes much of its heritage to knowledge gained from the wars of the twentieth century (History box).

Despite the economic downturn, 12.1 million cosmetic surgical procedures were performed [by surgeons certified by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS)] in 2008, an increase of 3%; the majority were minimally invasive procedures. Females constituted 91% of all patients undergoing cosmetic procedures. Hispanic, Asian, and African American patients showed an increase in cosmetic procedures; the number of Caucasians undergoing cosmetic procedures decreased by 2%. Office-based cosmetic procedures increased by 13%, with a total of $10.3 billion dollars spent on the cosmetic procedures in the United States (Ambulatory Surgery Considerations). The 4.9 million reconstructive procedures also showed a 3% increase, although breast reductions decreased by 16% (ASPS Stats, 2009).

Surgical Anatomy

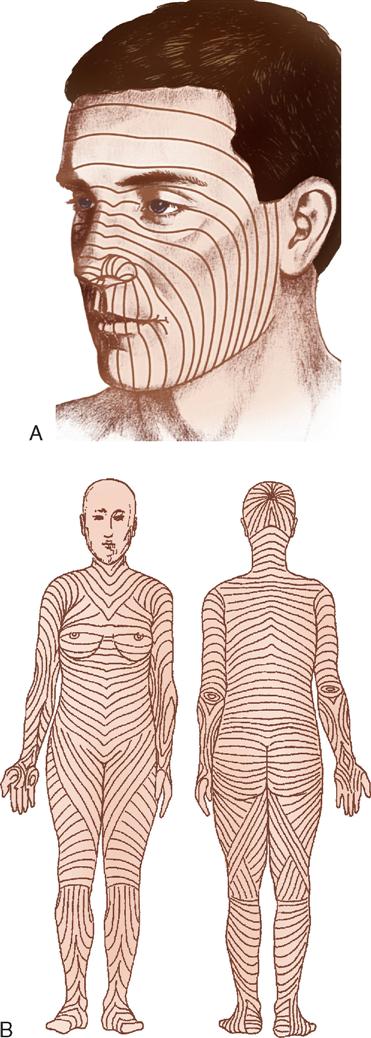

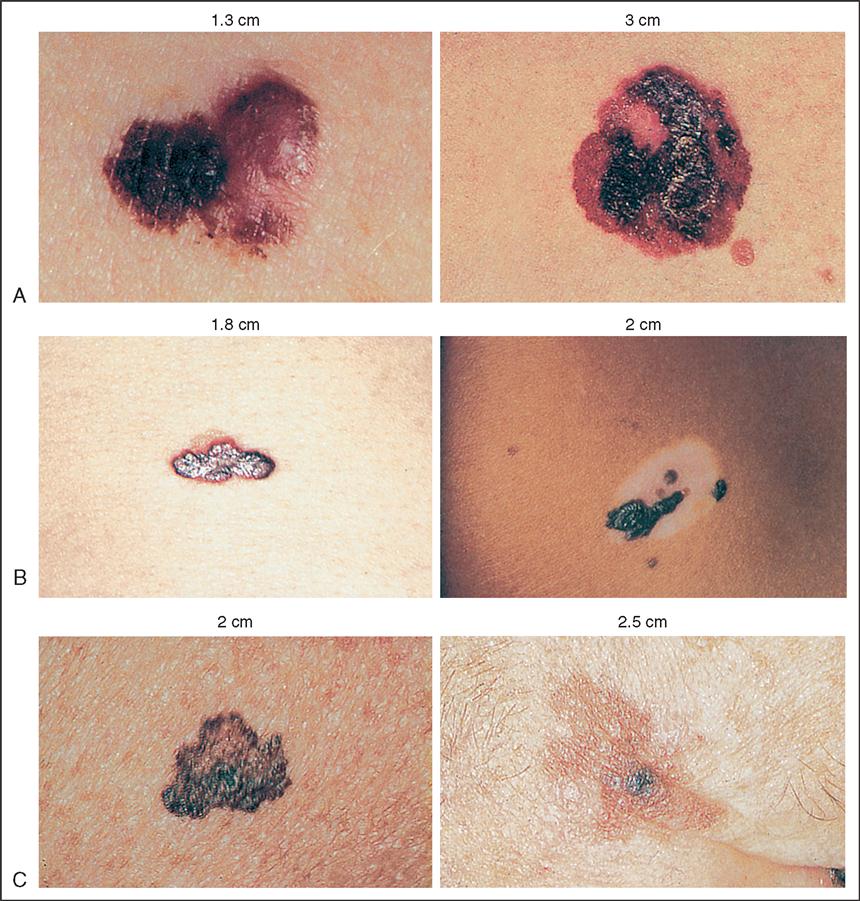

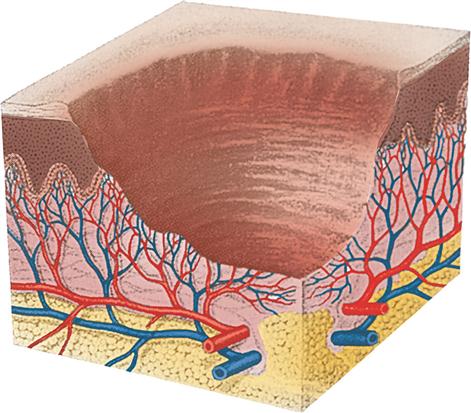

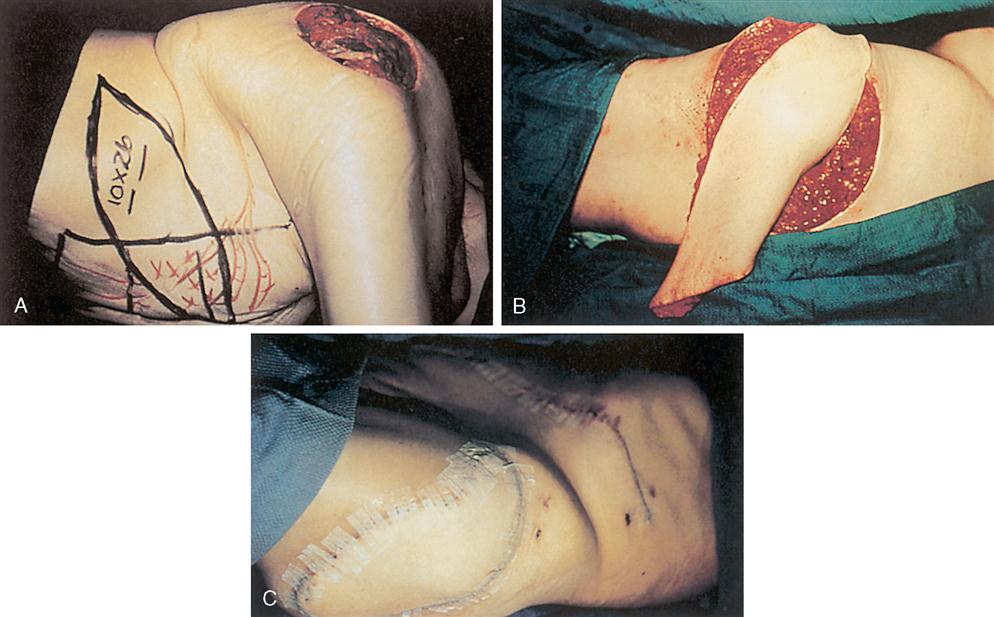

Plastic and reconstructive surgery is not limited to a single anatomic or biologic system. It is based on thorough understanding of the anatomy and biology of tissue. Operative techniques are complex and staged to achieve the expected results. The surgery also involves removing, reducing, enlarging, and recontouring, as well as camouflaging scars into existing skin lines (Figure 13-1). The tissues of the body can be transferred to use as various types of flaps. Free flaps are the transfer of tissue along with its vascular pedicle. When nerve is anastomosed with these flaps, they are called neurovascular free flaps. Flaps are used to cover defects or create new structures such as breasts, digits, or facial structures. Body parts can also be transplanted. By improving the patient’s deformity, the patient’s self-esteem will improve and the patient will feel more comfortable in public and social activities. The body changes as we age. The patient’s concern with aesthetics, the variety of acquired defects, the diversity of operative techniques, and the psychologic responses of patients offer unique learning experiences and challenges for perioperative patient care.

Surgical Technologist Considerations

Preparation of the OR Suite.

Assemble all necessary medical and surgical supplies, equipment, suture material, positioning aids, implantable devices, and medications. Ensure that lights and video equipment are in working order, that emergency supplies are present, and that compressed gases are adequate. Depending on the procedure to be performed, the OR bed may need to be configured differently from the standard room setup. Plastic and reconstructive surgeons frequently use preoperative photographs of the patient when attempting to restore or modify appearance. These photographs help the surgeon maintain perspective since features may change because of surgical positioning. Preoperative and postoperative photos, in order to be accurate, should be taken with the same lighting, angle, and distance (Hagan, 2008).

Equipment and Special Mechanical Devices.

Essential equipment for any OR includes a fully functional bed that may be positioned for any number of special needs and also has accessory attachments, such as headrests and aids for extremity positioning. The room must also have well-positioned and numerous electrical outlets, good overhead lighting, suction equipment, mounted x-ray view boxes, and computer terminals for those facilities using electronic medical records. Step stools, tables, chairs, hand tables, tourniquets, microscopes, and intravenous (IV) poles should be in appropriate supply and accessible. Surgeons often provide their own digital cameras although facilities may have them available for use.

INSTRUMENTATION.

Basic instrument trays are available for the plastic surgery OR. A “local” tray may include Bishop Harmon and adson tissue forceps (with and without teeth); straight and curved iris, Stevens, and Metzenbaum scissors; fine mosquito forceps; and skin hooks. Minor and major trays for plastic surgery may contain a range of tissue forceps, scissors, hemostats, and retractors. With the addition of instruments for specific surgeries, these trays usually suffice for all plastic surgery operations. Adequate instrumentation should be available to avoid flash sterilization (Risk Reduction strategies).

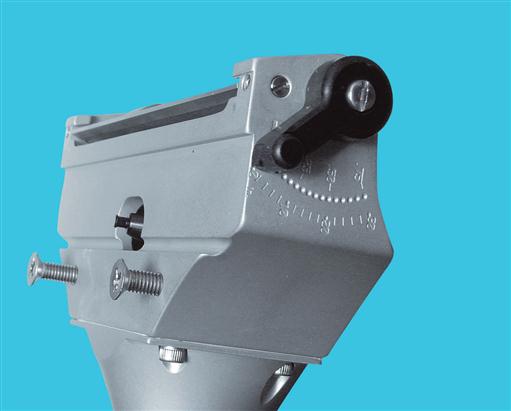

DERMATOMES.

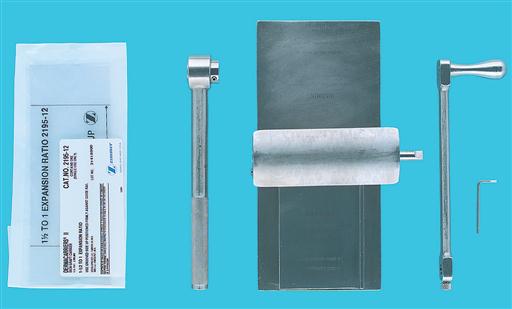

Dermatomes are used for removing split-thickness skin grafts (STSGS) from donor sites; they are of three basic types: knife, drum, and motor-driven (Figures 13-2 through 13-5). Sterile mineral oil and a tongue blade should be available when stsgs are being obtained.

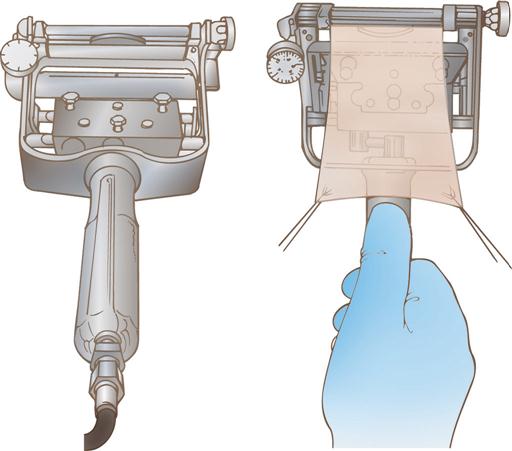

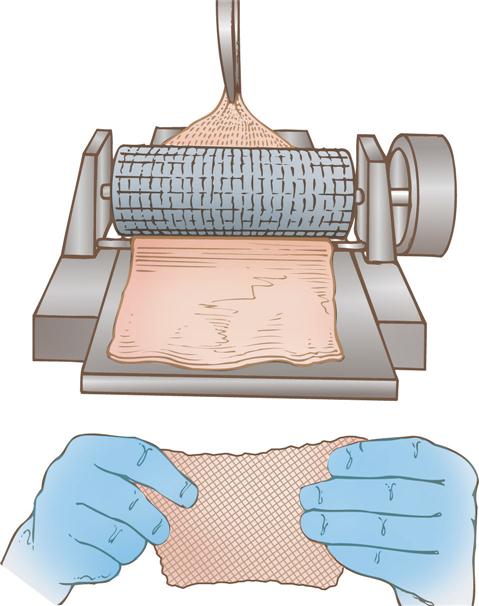

SKIN MESHERS.

Several types of skin meshers are available. Each is designed to produce multiple uniform slits in a skin graft, approximately 0.05 inch apart. These multiple apertures in the graft can then expand, permitting the skin graft to stretch and cover a larger area. Meshing also facilitates drainage through the graft, preventing fluid accumulation under a graft. The graft is placed on the carrier and passed through the mesher (Figures 13-6 and 13-7). The manufacturer supplies sterile carriers for meshers. They are usually available in several sizes, which determine the expansion ratio of the skin graft.

PNEUMATIC-POWERED INSTRUMENTS.

Pneumatic-powered instruments use an inert, nonflammable, and explosion-free compressed gas as their power source. The motor may be activated by a foot pedal or hand control. The various attachments should be sterilized as recommended by the manufacturer to prolong instrument life and ensure effective sterilization. The following attachments may be used in plastic surgery:

A pneumatic tourniquet with an inflatable cuff is used in most hand surgery procedures as well as in other upper and lower extremity surgical interventions. The tourniquet is described in Chapter 10.

ELECTROSURGICAL UNIT.

The electrosurgical unit (ESU) is employed and safety precautions should be followed. Monopolar ESU will require the use of a grounding pad (return electrode/dispersive electrode). Specialized tips will be used with the ESU pencil including needle point and guarded along with the standard tip. The use of specialized tips allows the use of higher coagulation settings to obtain hemostasis with little or no effect on adjacent tissue or structures. Inspect ESU tip and cord on handpiece for damage before use, be sure tip is securely seated into the place handpiece in nonconductive holster when not in use, keep tip free of eschar or tissue build-up. Methods to do so include moistened sponge, instrument wipe, and abrasive electrode cleaner, but not a scalpel blade.

BIPOLAR COAGULATION UNIT.

Bipolar electrosurgery is the use of electrical current in which the circuit is completed by means of two parallel poles located close to one another. One pole is positive; the other is negative. The flow of current is restricted between these two poles, which are usually the tines of the bipolar forceps. Because the poles are so close, low voltages are used to achieve the tissue effect. Because electrical current does not flow through the patient, a return electrode (dispersive pad) is not necessary. This makes bipolar electrosurgery very safe and permits precise electrocoagulation.

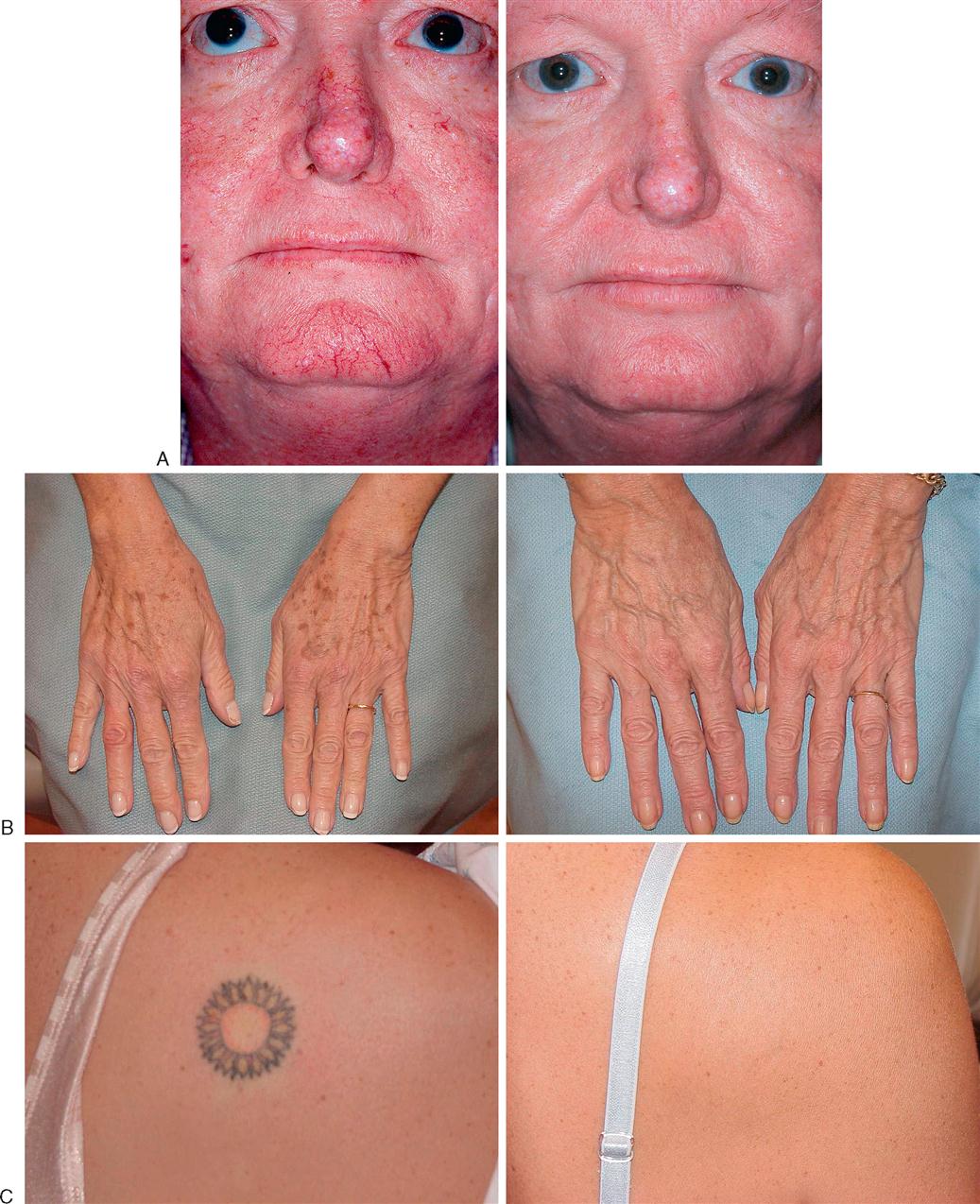

LASERS.

A variety of lasers are employed for plastic surgical procedures. The perioperative team must ensure that the laser safety accessories specific to the type of laser being used are available. Types of lasers and their common uses are presented in Box 13-3, pp. 637–639.

FIBEROPTIC INSTRUMENTS.

Examples of fiberoptic instrument attachments used in plastic surgery are a headlight for rhinoplasties, augmentation mammoplasties, and other procedures; a mammary retractor for augmentation mammoplasties; a rhytidectomy retractor; abdominoplasty retractors; and endoscopic face and forehead fiberoptic instrumentation.

LOUPES.

Loupes (Figure 13-8) are magnifying lenses used by many plastic surgeons for microvascular surgery and nerve repairs and for numerous other instances in which cosmetic results are improved by the magnification effect. The nurse should inquire about the use of loupes before the surgeon dons a headlight because adjustments will need to be made to the headlight alignment if the loupes are required in midprocedure. Adjusting or removing the headlight in midprocedure has the potential to contaminate the sterile field.

MICROSCOPE.

The microscope is frequently used in nerve repairs and microsurgical anastomoses; the nerves or vessels to be repaired, such as in hand surgery, and the suture used to do so (sometimes 9-0, 10-0, or even 11-0 size) can be finer than human hair and thus requires magnification. While each microscope has different features, an important matter to avoid confusion is whether the surgeon control overrides the assistant view, or if each can separately adjust the field of view.

WOOD’S LAMP.

The wood’s lamp is an ultraviolet lamp used in a darkened room to determine the viability of skin flaps. After IV injection of fluorescein, the blood vessels appear bright purple (the skin appears yellow). Sodium fluorescein is excreted in the urine, and patients should be informed of this.

SPECIAL SUPPLIES.

Surgeon-specific and procedure-specific special supplies are frequently added to instrument setups for plastic and reconstructive procedures. these commonly include the following: sterile marking pen or methylene blue; ruler; local anesthetic of choice for injection, with syringes and needles; and ESU, with active electrode (pencil) and tip of choice, with tip cleaner.

Sutures.

Sutures range from permanent to absorbable and include monofilament and multifilament materials. The surgical technologist should be a good steward of costly resources and should verify the type and number of sutures needed before opening suture packages, as well as needle preference, to prevent waste. Many plastic surgical procedures have multiple techniques, each of which necessitates very specific suture choices.

Dressings.

Dressings are an essential part of the operative procedure in plastic surgery and may contribute to the ultimate outcome of the surgical intervention. Dressings are usually applied while the patient is still anesthetized. In general, the dressing should accomplish the following five goals:

1. Immobilize the surgical part.

2. Apply even pressure over the wound.

4. Provide comfort for the patient.

Pressure dressings may be used to eliminate dead space, to prevent seroma and hematoma formation, and to prevent third spacing associated with liposuction and reconstructive procedures involving transfer of large muscle or tissue flaps. In some cases pressure can be achieved by the use of catheters or drains placed within the operative site and connected to closed-wound suction devices, such as a Hemovac or Jackson-Pratt. In smaller wounds a butterfly cannula may be inserted into the operative site, with the needle end placed into a red-top tube, such as a blood collection tube, that has a vacuum (evacuated tube).

Common general dressings and supplies available in sterile form and various sizes:

♦ Nonadherent gauze (e.g., Betadine gauze, Adaptic, Nu Gauze, Xeroform, Biobrane, Scarlet Red)

♦ Petrolatum gauze, ½ inch (or other packing material, such as Merocel sponge for nasal packing)

♦ Telfa

♦ Gauze dressing sponges, 4 × 4 inches, 2 × 2 inches

♦ Kling, Kerlix fluff, and Kerlix gauze rolls (2, 4, and 6 inches wide)

♦ Abdominal pads (most commonly used are 5 × 8 inches)

♦ Webril

♦ Tape (paper; silk; and foam; skin tapes, flesh-colored and regular [1/8, 1/4, 1/2, and 1 inch wide])

♦ Benzoin spray or swab or Mastoplast

♦ Coban

♦ Casting supplies and splints (as required for postoperative immobilization)

♦ Abdominal binders and other postoperative garments

♦ Slings

In some instances, such as a free flap, transparent dressings are used so that the flap can be monitored and observed for vascular flow. Compression garments and support devices are also frequently used by plastic surgeons. Proper fit is essential to minimize vascular compromise. Compression garments are typically applied over a light dressing. A proper garment is selected based on its characteristics (e.g., fabric, stretch, softness, antimicrobial properties) and proper sizing according to measurement instructions. Educating patients of the needs and benefits of compression garment use as well as providing hints for their proper application (avoid ripping with long nails, instructions on how to don the garment) promotes comfort and compliance (Gladfelter, 2007).

Implant Materials.

The range of materials available for implantation and augmentation in the specialty of plastic and reconstructive surgery has benefited from ongoing research. The perioperative team is responsible for complying with tracking regulations for implantable materials and devices (Patient Safety).

Biologic materials (autogenous grafts) are preferred when available. Autologous human tissue successfully utilized includes fat, solid dermis, and collagen. Human cadavers are used as a source for acellular collagen (AlloDerm) (Figure 13-9). This product is available in various sizes of sheeting and must be rehydrated in several steps. AlloDerm integrates with the body’s tissue and helps to prevent rejection over the long term.

Implant failure may be directly linked to bacterial contamination; therefore meticulous aseptic technique with minimal handling is essential when using implants of any sort. Most alloplastic implants are presterilized from the manufacturer.

Anesthesia.

A variety of anesthesia techniques are employed with plastic surgery procedures. Local, regional, tumescent, conscious sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia may be used, depending on the type of procedure, the patient’s anesthetic history, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, and the surgeon’s preference.

Preoperative Skin Preparation.

Most surgical interventions require that the operative site and adjacent areas be cleansed before surgery. The physician may prescribe that the patient carry out this treatment before surgery. Special attention is given to the fingernails for patients undergoing hand surgery; to hair for surgery of the head, face, or neck; and to oral hygiene for surgery in or near the mouth. Shaving is avoided and clippers, not a razor, are used if needed, because shaving creates an access for the entry of bacteria into the operative site (Health Stream, 2007). The eyebrows and eyelashes, in particular, are left intact to preserve facial appearance and expression. The surgical site is marked before surgery by the surgeon to designate the correct site and to define landmark areas. Either a povidone-iodine solution, an iodine-alcohol mixture, chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG), or another broad-spectrum agent may be selected for the antimicrobial skin prep. The use of CHG should be avoided around the ears and eyes. It is important to place shields on the eyes if prepping the periorbital site or performing an extensive head and neck prep, place plugs in the ear canals, and prevent pooling of the prep agent. When prepping for a skin graft procedure, separate skin prep setups are needed for the graft and donor sites.

Positioning and Draping.

The OR bed must be positioned so that the remaining space in the room can comfortably accommodate anesthetic equipment, members of the surgical team, instrument tables, and any adjunct equipment (hand table, drills, microscope, laser) to be used. The patient is carefully positioned on the OR bed so that all operative sites may be appropriately exposed and the airway easily observed and accessed.