Definition

Acute kidney injury (AKI), previously known as acute renal failure (ARF), is characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function that limits its ability to maintain homeostasis and eliminate nitrogenous waste. AKI is found in 7% of all hospitalized patients and up to 30% of critically ill patients.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), previously known as acute renal failure (ARF), is characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function that limits its ability to maintain homeostasis and eliminate nitrogenous waste. AKI is found in 7% of all hospitalized patients and up to 30% of critically ill patients.

AKI is defined as any of the following:

AKI is defined as any of the following:

Increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours.

Increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours.

Increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days.

Increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days.

Urine volume of <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours.

Urine volume of <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours.

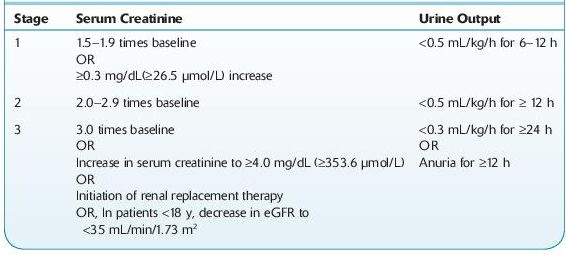

AKI is staged for severity based on serum creatinine level and urine output (see Table 12-1).

AKI is staged for severity based on serum creatinine level and urine output (see Table 12-1).

Causes of AKI can be divided into three categories:

Causes of AKI can be divided into three categories:

Prerenal: hypovolemia (e.g., hemorrhage, dehydration, burns), anaphylactic or septic shock, heart failure, or decreased renal perfusion due to drugs or toxins

Prerenal: hypovolemia (e.g., hemorrhage, dehydration, burns), anaphylactic or septic shock, heart failure, or decreased renal perfusion due to drugs or toxins

Renal (intrinsic): acute tubular necrosis due to renal ischemia, nephrotoxic drugs or toxins, or acute renal diseases (e.g., acute glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis)

Renal (intrinsic): acute tubular necrosis due to renal ischemia, nephrotoxic drugs or toxins, or acute renal diseases (e.g., acute glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis)

Postrenal: due to obstruction of the urinary flow

Postrenal: due to obstruction of the urinary flow

TABLE 12–1. Staging of Acute Kidney Injury

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Source: Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group.

KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(Suppl):1–138.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Patients with AKI present in a variety of ways:

Patients with symptoms suggestive of uremia. The term uremia describes the clinical syndrome associated with retention of the end products of nitrogen metabolism due to severe reduction in renal function. It can be a consequence of either acute or chronic renal disease.

Patients with symptoms suggestive of uremia. The term uremia describes the clinical syndrome associated with retention of the end products of nitrogen metabolism due to severe reduction in renal function. It can be a consequence of either acute or chronic renal disease.

Patients with oliguria (urine output of <500 mL/day) or anuria (urine output <100 mL/day).

Patients with oliguria (urine output of <500 mL/day) or anuria (urine output <100 mL/day).

Patients with an elevated serum creatinine level.

Patients with an elevated serum creatinine level.

Hospitalized patients with severe losses of extracellular fluid or patients exposed to nephrotoxic drugs, sepsis, or radiographic contrast agents who demonstrate the symptoms or findings described above.

Hospitalized patients with severe losses of extracellular fluid or patients exposed to nephrotoxic drugs, sepsis, or radiographic contrast agents who demonstrate the symptoms or findings described above.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

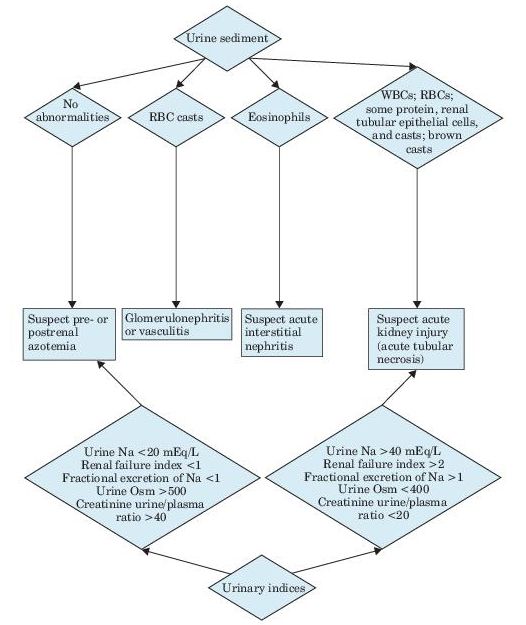

Urinalysis is the most important noninvasive test in the diagnosis of AKI and its etiology (see Figure 12-1). Microscopic examination is normal in most cases of prerenal disease. The presence of RBC casts or dysmorphic RBCs indicates glomerular disease, whereas finding cellular debris or granular casts suggests ischemic or nephrotoxic AKI. Urine specific gravity is of limited value in establishing the etiology of AKI.

Urinalysis is the most important noninvasive test in the diagnosis of AKI and its etiology (see Figure 12-1). Microscopic examination is normal in most cases of prerenal disease. The presence of RBC casts or dysmorphic RBCs indicates glomerular disease, whereas finding cellular debris or granular casts suggests ischemic or nephrotoxic AKI. Urine specific gravity is of limited value in establishing the etiology of AKI.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) gives an approximate estimation of the number of functioning nephrons and may be markedly reduced in patients with AKI. Estimation of GFR has a prognostic rather than diagnostic utility in AKI.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) gives an approximate estimation of the number of functioning nephrons and may be markedly reduced in patients with AKI. Estimation of GFR has a prognostic rather than diagnostic utility in AKI.

Serum creatinine level is elevated at diagnosis and continues to rise. The rate of rise may be helpful in determining the etiology of AKI.

Serum creatinine level is elevated at diagnosis and continues to rise. The rate of rise may be helpful in determining the etiology of AKI.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/serum creatinine ratio is normal in intrinsic renal disease (10–15:1) and elevated (>20:1) in prerenal azotemia.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/serum creatinine ratio is normal in intrinsic renal disease (10–15:1) and elevated (>20:1) in prerenal azotemia.

Urine-to-serum creatinine ratio is high in patients with prerenal disease and low with renal causes of AKI.

Urine-to-serum creatinine ratio is high in patients with prerenal disease and low with renal causes of AKI.

Patients with postrenal disease are diagnosed based on clinical presentation and imaging studies.

Patients with postrenal disease are diagnosed based on clinical presentation and imaging studies.

Several protein biomarkers have been found to signal AKI prior to the rise in serum creatinine. These candidate biomarkers include, but not limited to, kidney injury molecule-I (KIM-1), N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG), neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin (NGAL), retinol-binding protein and interleukin (IL)-18.

Several protein biomarkers have been found to signal AKI prior to the rise in serum creatinine. These candidate biomarkers include, but not limited to, kidney injury molecule-I (KIM-1), N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG), neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin (NGAL), retinol-binding protein and interleukin (IL)-18.

See Table 12-2.

See Table 12-2.

Figure 12–1 Algorithm for the diagnosis of acute kidney injury.

TABLE 12–2. Urinary Diagnostic Indices in Acute Kidney Injury

H, high; L, low; N, normal; U/P, urine/plasma ratio; V, variable.

*Polyuria may be present.

Sources: Andreoli TE, et al., eds. Cecil Essentials of Medicine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1990;212; Okum DE. On the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Am J Med. 1981;71:916; Schrier RW. Acute renal failure: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Hosp Pract. 1981;16:9398; Miller TR, et al. Urinary diagnostic indices in acute renal failure: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:47.

Suggested Readings

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;(Suppl 2):1–138. http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO%20AKI%20Guideline.pdf

Vaidya VS, Ferguson MA, Bonventre JV. Biomarkers of acute kidney injury. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:463–493.

ACUTE TUBULAR NECROSIS

Definition

Definition

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is an acute disorder of kidney function associated with injury to the renal tubular epithelial cells.

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is an acute disorder of kidney function associated with injury to the renal tubular epithelial cells.

ATN develops in the context of renal ischemia (ischemic ATN) or exposure to nephrotoxins (nephrotoxic ATN). It is associated with high mortality rate.

ATN develops in the context of renal ischemia (ischemic ATN) or exposure to nephrotoxins (nephrotoxic ATN). It is associated with high mortality rate.

Prerenal disease and ATN are the most common causes of hospital-acquired AKI.

Prerenal disease and ATN are the most common causes of hospital-acquired AKI.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Candidates for investigation include patients (in most cases hospitalized) with exposure to a nephrotoxin (e.g., therapy with aminoglycoside or amphotericin B, radiologic contrast materials, heavy metals, cisplatin, ethylene glycol, or heme pigments such as free hemoglobin or myoglobin), severe trauma, hemorrhage, hypotension, surgery or sepsis, and recent-onset oliguria or anuria.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Urinalysis: sloughed renal tubular epithelial cells muddy brown epithelial and granular casts; hyaline casts may be seen. Urine volume is typically, but not invariably, low.

Urinalysis: sloughed renal tubular epithelial cells muddy brown epithelial and granular casts; hyaline casts may be seen. Urine volume is typically, but not invariably, low.

Urine osmolality is typically below 400 mOsm/kg.

Urine osmolality is typically below 400 mOsm/kg.

Fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) is an accurate test to differentiate between prerenal disease (<1%) and ATN (>1%). There are few limitations, however, to the use of FENa in determining the cause of AKI since it may be <1% in some ATN cases (e.g., when ATN is associated with a chronic prerenal disease such as heart failure), or >1% in some prerenal disease cases (e.g., patients treated with diuretics).

Fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) is an accurate test to differentiate between prerenal disease (<1%) and ATN (>1%). There are few limitations, however, to the use of FENa in determining the cause of AKI since it may be <1% in some ATN cases (e.g., when ATN is associated with a chronic prerenal disease such as heart failure), or >1% in some prerenal disease cases (e.g., patients treated with diuretics).

Sudden elevation in serum creatinine with normal BUN/creatinine ratio (10–15:1).

Sudden elevation in serum creatinine with normal BUN/creatinine ratio (10–15:1).

CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Definition

Definition

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) occurs when there is a progressive, irreversible alteration in kidney structure and function, as reflected by a gradual decrease in GFR and increase in BUN and creatinine, and/or albuminuria. This condition becomes more prevalent with increasing age.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) occurs when there is a progressive, irreversible alteration in kidney structure and function, as reflected by a gradual decrease in GFR and increase in BUN and creatinine, and/or albuminuria. This condition becomes more prevalent with increasing age.

CKD is defined by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) as

CKD is defined by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) as

Kidney damage for ≥3 months as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, manifested by either pathologic abnormalities or markers of kidney damage

Kidney damage for ≥3 months as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, manifested by either pathologic abnormalities or markers of kidney damage

GFR <60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 for ≥3 months, with or without kidney damage

GFR <60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 for ≥3 months, with or without kidney damage

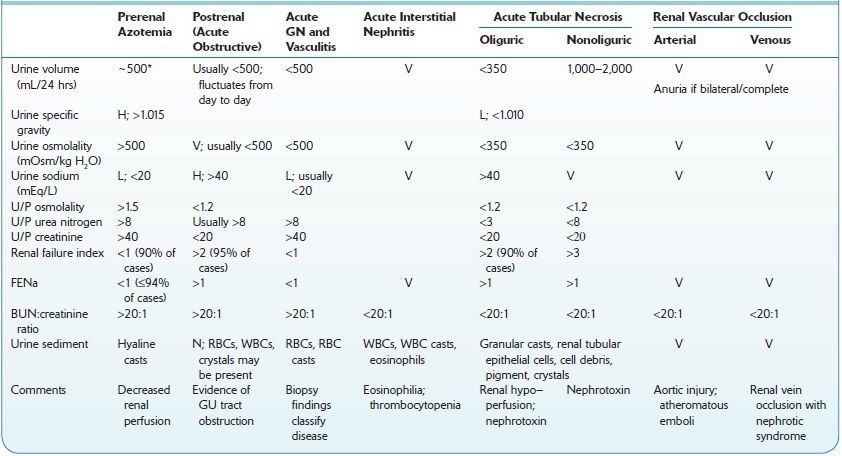

CKD is divided into five stages based on GFR (see Table 12-3). Stage 5 or kidney failure is the most advanced stage. The term end-stage renal disease (ESRS) refers to chronic kidney failure treated with either dialysis or transplantation.

CKD is divided into five stages based on GFR (see Table 12-3). Stage 5 or kidney failure is the most advanced stage. The term end-stage renal disease (ESRS) refers to chronic kidney failure treated with either dialysis or transplantation.

CKD is usually asymptomatic in its early stages (1–3). Symptoms and metabolic complications (e.g., anemia, hyperparathyroidism, water and electrolyte imbalance) usually appear at later stages when GFR drops below 30 mL/ minute/1.73 m2.

CKD is usually asymptomatic in its early stages (1–3). Symptoms and metabolic complications (e.g., anemia, hyperparathyroidism, water and electrolyte imbalance) usually appear at later stages when GFR drops below 30 mL/ minute/1.73 m2.

Another staging system uses urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g): stage 1: <30 mg/g; stage 2: 30–299 mg/g; stage 3 ≥ 300 mg/g.

Another staging system uses urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g): stage 1: <30 mg/g; stage 2: 30–299 mg/g; stage 3 ≥ 300 mg/g.

The distinction between acute, subacute, and chronic kidney disease is not always well defined but may be important, since AKI may be reversible, whereas CKD is not. A reduced size of the kidney (demonstrated by ultrasound) indicates a chronic phase.

The distinction between acute, subacute, and chronic kidney disease is not always well defined but may be important, since AKI may be reversible, whereas CKD is not. A reduced size of the kidney (demonstrated by ultrasound) indicates a chronic phase.

The majority of CKD cases are due to glomerular disease, tubular or interstitial disease, or long-standing obstructive uropathy.

The majority of CKD cases are due to glomerular disease, tubular or interstitial disease, or long-standing obstructive uropathy.

TABLE 12–3. Classification and Clinical Action Plan for Chronic Kidney Disease

Shaded area identifies patients who have chronic kidney disease; unshaded area designates individuals who are at increased risk for developing chronic kidney disease.

*Includes actions from preceding stages.

GFR, glomerular filtration rate; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Source: National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(Suppl 1):S1–S266.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Patients who have had acute renal injury or glomerulonephritis.

Patients who have had acute renal injury or glomerulonephritis.

Patients with diseases that can initiate or propagate kidney disease, such as diabetes or hypertension.

Patients with diseases that can initiate or propagate kidney disease, such as diabetes or hypertension.

Those in whom symptoms develop insidiously suggesting uremia (easy fatigability, anorexia, vomiting, mental status changes, seizures) or generalized edema.

Those in whom symptoms develop insidiously suggesting uremia (easy fatigability, anorexia, vomiting, mental status changes, seizures) or generalized edema.

Those in whom renal function or urinalysis abnormalities are discovered incidentally.

Those in whom renal function or urinalysis abnormalities are discovered incidentally.

Those with a family history of CKD or have a congenital renal abnormality.

Those with a family history of CKD or have a congenital renal abnormality.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory studies are indicated once renal disease is suspected. Until renal insufficiency is severe, adaptation of tubular function allows excretion of relatively normal amounts of water and sodium.

Serum creatinine and BUN increase in parallel.

Serum creatinine and BUN increase in parallel.

Creatinine clearance, established via well-accepted formulas, is used to estimate the GFR (estimated GFR or eGFR). This parameter is generally considered the best index of overall kidney function and repeated determinations, in conjunction with creatinine measurement, establish whether the patient has stable or progressive disease. GFR has no etiologic diagnostic value.

Creatinine clearance, established via well-accepted formulas, is used to estimate the GFR (estimated GFR or eGFR). This parameter is generally considered the best index of overall kidney function and repeated determinations, in conjunction with creatinine measurement, establish whether the patient has stable or progressive disease. GFR has no etiologic diagnostic value.

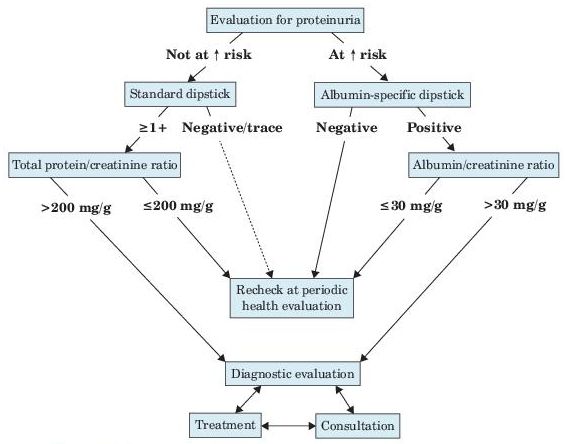

Albuminuria is a marker of kidney damage that is commonly determined by measuring albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) in untimed “spot” urine. An ACR cutoff of 30 mg/g indicates abnormality (see Figure 12-2).

Albuminuria is a marker of kidney damage that is commonly determined by measuring albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) in untimed “spot” urine. An ACR cutoff of 30 mg/g indicates abnormality (see Figure 12-2).

Urinalysis

Urinalysis

Microscopic examination is an important tool in determining the etiology of CKD. WBCs, RBCs, and casts are usually found.

Microscopic examination is an important tool in determining the etiology of CKD. WBCs, RBCs, and casts are usually found.

Dipstick examination for albumin, glucose, pH, nitrate, and blood contribute to determining the etiology of CKD.

Dipstick examination for albumin, glucose, pH, nitrate, and blood contribute to determining the etiology of CKD.

Blood pH measurement can be helpful since acidosis is a frequent complication of advanced CKD.

Blood pH measurement can be helpful since acidosis is a frequent complication of advanced CKD.

Serum abnormalities include hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and hypermagnesemia. Uric acid and amylase may also be increased.

Serum abnormalities include hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and hypermagnesemia. Uric acid and amylase may also be increased.

Hypoalbuminemia and hyperlipidemia (increased triglycerides, cholesterol, and VLDL lipoprotein levels) may occur, and they are common in the nephrotic syndrome. Hypergammaglobulinemia with monoclonal gammopathy suggests myeloma kidney as the etiology of CKD.

Hypoalbuminemia and hyperlipidemia (increased triglycerides, cholesterol, and VLDL lipoprotein levels) may occur, and they are common in the nephrotic syndrome. Hypergammaglobulinemia with monoclonal gammopathy suggests myeloma kidney as the etiology of CKD.

Anemia is caused by reduction in the synthesis of erythropoietin and usually develops with reduction of renal function to 30–50% of normal.

Anemia is caused by reduction in the synthesis of erythropoietin and usually develops with reduction of renal function to 30–50% of normal.

Coagulation studies may be affected by uremic by-products such as guanidinosuccinic acid and exuberant production of nitrous oxide by uremic vessels, resulting in abnormal platelet function.

Coagulation studies may be affected by uremic by-products such as guanidinosuccinic acid and exuberant production of nitrous oxide by uremic vessels, resulting in abnormal platelet function.

Figure 12–2 Evaluation of proteinuria in patients not known to have kidney disease.

Suggested Readings

National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(Suppl 1):S1–S266. http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/pdf/ckd_evaluation_classification_stratification.pdf

Stevens PE, Levin A, et al. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):825–830.

FOCAL SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS

Definition

Definition

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a histologic lesion that is commonly found to underlie the nephrotic syndrome. It accounts for 20% of nephrotic syndrome cases in children and 40% of such cases in adults. In addition, it is the most common pathology identified in patients with ESRD.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a histologic lesion that is commonly found to underlie the nephrotic syndrome. It accounts for 20% of nephrotic syndrome cases in children and 40% of such cases in adults. In addition, it is the most common pathology identified in patients with ESRD.

Classified as

Classified as

Primary (idiopathic): commonly presents with nephrotic syndrome and accounts for approximately 80% of FSGS cases

Primary (idiopathic): commonly presents with nephrotic syndrome and accounts for approximately 80% of FSGS cases

Secondary: due to diseases (e.g., vasculitis, SLE), infections (e.g., HIV, hepatitis B), drugs, toxins, malignancies, or genetic abnormalities (familial). Patients present with slowly progressing renal insufficiency over time.

Secondary: due to diseases (e.g., vasculitis, SLE), infections (e.g., HIV, hepatitis B), drugs, toxins, malignancies, or genetic abnormalities (familial). Patients present with slowly progressing renal insufficiency over time.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Marked proteinuria; nephrotic range (>3.5 g/day) in primary FSGS and nonnephrotic in secondary FSGS.

Marked proteinuria; nephrotic range (>3.5 g/day) in primary FSGS and nonnephrotic in secondary FSGS.

Hypoalbuminemia (more common in primary FSGS).

Hypoalbuminemia (more common in primary FSGS).

Hypercholesterolemia and peripheral edema can occur.

Hypercholesterolemia and peripheral edema can occur.

Hematuria, microscopic and macroscopic.

Hematuria, microscopic and macroscopic.

Serum level of soluble urokinase receptor is elevated.

Serum level of soluble urokinase receptor is elevated.

Histologic findings are used to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologic findings are used to confirm the diagnosis.

Suggested Reading

D’Agati VD, Kaskel FJ, Falk RJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(25): 2398–2411.

GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

Definition and Classification

Definition and Classification

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a renal disease characterized by inflammation of the glomeruli and hematuria. It can be acute or chronic and is often associated with decreased GFR, proteinuria, edema, hypertension, and sometimes oliguria.

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a renal disease characterized by inflammation of the glomeruli and hematuria. It can be acute or chronic and is often associated with decreased GFR, proteinuria, edema, hypertension, and sometimes oliguria.

Acute GN is defined as the sudden onset of hematuria, proteinuria, and RBC casts.

Acute GN is defined as the sudden onset of hematuria, proteinuria, and RBC casts.

Chronic GN can develop over years and, in a subset of patients, can ultimately lead to renal failure.

Chronic GN can develop over years and, in a subset of patients, can ultimately lead to renal failure.

GN disorders can be grouped into nonproliferative and proliferative types.

GN disorders can be grouped into nonproliferative and proliferative types.

Non-proliferative GN disorders include

Non-proliferative GN disorders include

Focal segmented glomerulosclerosis

Focal segmented glomerulosclerosis

Membranous glomerulopathy

Membranous glomerulopathy

Minimal change disease

Minimal change disease

Proliferative GN disorders include

Proliferative GN disorders include

IgA nephropathy

IgA nephropathy

Postinfectious GN

Postinfectious GN

Membranoproliferative GN

Membranoproliferative GN

Rapidly progressive GN

Rapidly progressive GN

GN can be a primary disorder due to causes intrinsic to the kidney or secondary to autoimmune disorders, infections, diabetes, or drug treatment.

GN can be a primary disorder due to causes intrinsic to the kidney or secondary to autoimmune disorders, infections, diabetes, or drug treatment.

Conditions associated with GN can be also classified as antibody-mediated or cell-mediated, infectious or noninfectious, or hypocomplementemic or normocomplementemic.

Conditions associated with GN can be also classified as antibody-mediated or cell-mediated, infectious or noninfectious, or hypocomplementemic or normocomplementemic.

Antibody Mediated

For example, anti–glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease (Goodpasture syndrome), following renal transplantation

For example, anti–glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease (Goodpasture syndrome), following renal transplantation

Immune complex–mediated diseases (typically show hypocomplementemia): for example, IgA nephropathy, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), acute postinfectious GN, membranoproliferative GN

Immune complex–mediated diseases (typically show hypocomplementemia): for example, IgA nephropathy, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), acute postinfectious GN, membranoproliferative GN

Cell Mediated

Examples include Wegener granulomatosis, polyarteritis.

Examples include Wegener granulomatosis, polyarteritis.

Infectious

Acute poststreptococcal (group A beta-hemolytic GN)

Acute poststreptococcal (group A beta-hemolytic GN)

Non-poststreptococcal: bacterial (e.g., infective endocarditis, bacteremia), viral (e.g., HBV, HCV, CMV infections), parasitic (e.g., trichinosis, toxoplasmosis, malaria), or fungal

Non-poststreptococcal: bacterial (e.g., infective endocarditis, bacteremia), viral (e.g., HBV, HCV, CMV infections), parasitic (e.g., trichinosis, toxoplasmosis, malaria), or fungal

Noninfectious

Multisystem (e.g., SLE, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Goodpasture syndrome, Alport syndrome)

Multisystem (e.g., SLE, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Goodpasture syndrome, Alport syndrome)

Primary glomerular disease (e.g., IgA nephropathy, membranoproliferative GN)

Primary glomerular disease (e.g., IgA nephropathy, membranoproliferative GN)

Hypocomplementemic

Intrinsic renal diseases (especially poststreptococcal, membranoproliferative GN)

Intrinsic renal diseases (especially poststreptococcal, membranoproliferative GN)

Systemic (e.g., SLE, cryoglobulinemia)

Systemic (e.g., SLE, cryoglobulinemia)

Normocomplementemic

Intrinsic renal diseases (e.g., IgA nephropathy, idiopathic rapidly progressive GN)

Intrinsic renal diseases (e.g., IgA nephropathy, idiopathic rapidly progressive GN)

Systemic (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener granulomatosis)

Systemic (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener granulomatosis)

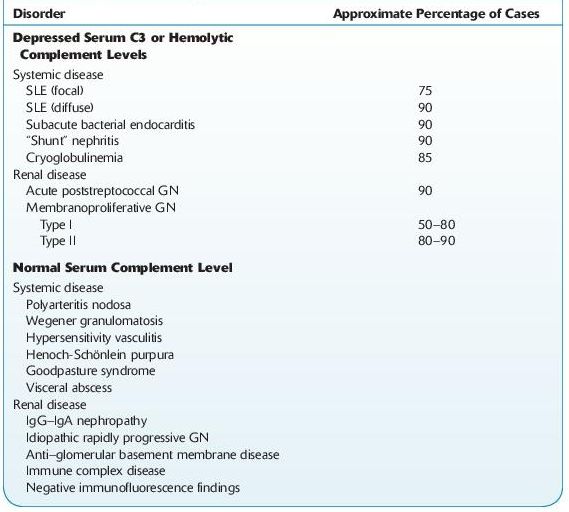

See Table 12-4.

See Table 12-4.

TABLE 12–4. Serum Complement in Acute Nephritis

Various Clinical Courses of GN

Various Clinical Courses of GN

The clinical spectrum of GN comprises:

Asymptomatic subnephrotic proteinuria without hematuria.

Asymptomatic subnephrotic proteinuria without hematuria.

Asymptomatic proteinuria with hematuria: the coexistence of asymptomatic proteinuria and hematuria substantially increases the risk of significant glomerular damage, hypertension, and progressive renal dysfunction in comparison to the situation of isolated asymptomatic proteinuria.

Asymptomatic proteinuria with hematuria: the coexistence of asymptomatic proteinuria and hematuria substantially increases the risk of significant glomerular damage, hypertension, and progressive renal dysfunction in comparison to the situation of isolated asymptomatic proteinuria.

Nephrotic syndrome: proteinuria in excess of 3.5 g in 24 hours, accompanied by edema, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and lipiduria.

Nephrotic syndrome: proteinuria in excess of 3.5 g in 24 hours, accompanied by edema, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and lipiduria.

Nephritic syndrome: nonnephrotic proteinuria, hematuria, and appearing tendency to GFR lowering.

Nephritic syndrome: nonnephrotic proteinuria, hematuria, and appearing tendency to GFR lowering.

Course of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, including non-nephrotic proteinuria, hematuria with rapid GFR decline, and acute renal failure.

Course of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, including non-nephrotic proteinuria, hematuria with rapid GFR decline, and acute renal failure.

Macroscopic hematuria associated with glomerular diseases, appearing mainly in children and young adults as a symptom of IgA nephropathy and postinfectious GN. The characteristic feature of IgA nephropathy is episodic frank hematuria occurring simultaneously with an upper respiratory tract infection, whereas in postinfectious GN, there is a 2- to 3-week period of latency between infection and hematuria.

Macroscopic hematuria associated with glomerular diseases, appearing mainly in children and young adults as a symptom of IgA nephropathy and postinfectious GN. The characteristic feature of IgA nephropathy is episodic frank hematuria occurring simultaneously with an upper respiratory tract infection, whereas in postinfectious GN, there is a 2- to 3-week period of latency between infection and hematuria.

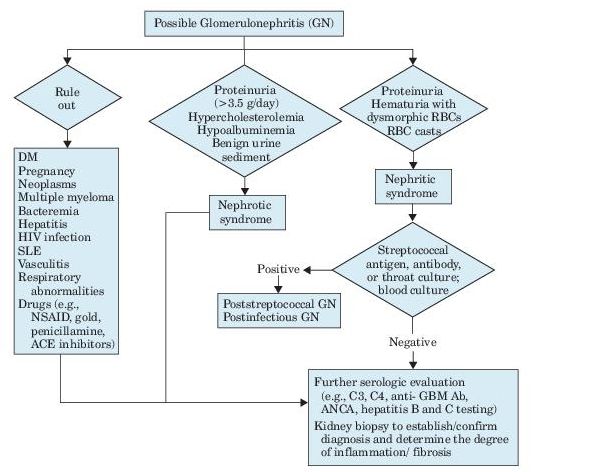

See Figure 12-3.

See Figure 12-3.

Figure 12–3 Algorithm for evaluation of glomerulonephritis.

Suggested Reading

Klinger M, Mazanowska O. Primary idiopathic glomerulonephritis: modern algorithm for diagnosis and treatment. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2008;118(10):567–571.

GLOMERULONEPHRITIS, MEMBRANOPROLIFERATIVE

Definition

Definition

Membranoproliferative GN (MPGN) accounts for approximately 10% of all cases of biopsy-confirmed glomerulonephritis and ranks as the third leading cause of end-stage renal disease among the primary glomerulonephritides.

Membranoproliferative GN (MPGN) accounts for approximately 10% of all cases of biopsy-confirmed glomerulonephritis and ranks as the third leading cause of end-stage renal disease among the primary glomerulonephritides.

MPGN can be primary or secondary to systemic diseases (e.g., SLE), neoplasms, monoclonal gammopathy, or infections (especially HCV with cryoglobulinemia).

MPGN can be primary or secondary to systemic diseases (e.g., SLE), neoplasms, monoclonal gammopathy, or infections (especially HCV with cryoglobulinemia).

MPGN most commonly presents in childhood but can occur at any age. Patients can present with a variety of findings ranging from microscopic hematuria to severe glomerulonephritis associated with hypertension and nephrotic syndrome. The clinical course may be clinically active, or there may be periods of remission. Approximately 50% of untreated patients have chronic renal insufficiency in 10 years.

MPGN most commonly presents in childhood but can occur at any age. Patients can present with a variety of findings ranging from microscopic hematuria to severe glomerulonephritis associated with hypertension and nephrotic syndrome. The clinical course may be clinically active, or there may be periods of remission. Approximately 50% of untreated patients have chronic renal insufficiency in 10 years.

On the basis of the electron microscopical findings, MPGN is traditionally classified as type I (idiopathic, most common), type II, or type III (rare). In another classification that is more useful and based on the pathogenetic process, MPGN can be classified as immune complex mediated, complement mediated, or MPGN without immunoglobulin or complement deposition.

On the basis of the electron microscopical findings, MPGN is traditionally classified as type I (idiopathic, most common), type II, or type III (rare). In another classification that is more useful and based on the pathogenetic process, MPGN can be classified as immune complex mediated, complement mediated, or MPGN without immunoglobulin or complement deposition.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Variable degree of proteinuria, which can be marked or reach the nephrotic range.

Variable degree of proteinuria, which can be marked or reach the nephrotic range.

Hematuria is present in patients with active disease.

Hematuria is present in patients with active disease.

Decreased serum levels of complement C3. C4 may be normal or decreased. Clinical course is not related to serum complement levels.

Decreased serum levels of complement C3. C4 may be normal or decreased. Clinical course is not related to serum complement levels.

GFR <80 mL/minute/1.73/m2 in two thirds of patients.

GFR <80 mL/minute/1.73/m2 in two thirds of patients.

Relevant tests for the detection of secondary causes may be helpful (e.g., serologic testing and culture to detect infections, anti-GBM antibodies, cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and antinuclear antibody testing).

Relevant tests for the detection of secondary causes may be helpful (e.g., serologic testing and culture to detect infections, anti-GBM antibodies, cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, and antinuclear antibody testing).

Suggested Reading

Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis—a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1119–1131.

GLOMERULONEPHRITIS, MEMBRANOUS

Definition

Definition

Membranous GN is an antibody-mediated disorder in which immune complexes localize between the outer aspect of glomerular basement membrane and epithelial cells. These complexes are formed by binding of antibodies to antigens that are part of the basement membrane, or deposited from elsewhere by the systemic circulation.

Membranous GN is an antibody-mediated disorder in which immune complexes localize between the outer aspect of glomerular basement membrane and epithelial cells. These complexes are formed by binding of antibodies to antigens that are part of the basement membrane, or deposited from elsewhere by the systemic circulation.

It usually occurs in adults and is the second most common cause of nephrotic syndrome.

It usually occurs in adults and is the second most common cause of nephrotic syndrome.

It may be primary (≥75% of cases) or secondary. Secondary membranous GN may be due to autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE), infections (e.g., HBV, syphilis, malaria, schistosomiasis, leprosy), drugs (e.g., NSAIDs, penicillamine), or neoplasms (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia, carcinomas, melanoma).

It may be primary (≥75% of cases) or secondary. Secondary membranous GN may be due to autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE), infections (e.g., HBV, syphilis, malaria, schistosomiasis, leprosy), drugs (e.g., NSAIDs, penicillamine), or neoplasms (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia, carcinomas, melanoma).

Approximately 20% of patients will progress to ESRD in 20–30 years.

Approximately 20% of patients will progress to ESRD in 20–30 years.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Marked proteinuria; nephrotic syndrome is found in many patients.

Marked proteinuria; nephrotic syndrome is found in many patients.

Microscopic hematuria may be present.

Microscopic hematuria may be present.

Autoantibodies against phospholipase-A2 receptor (PLA2R-Ab), mostly of the IgG4 class, can be found in 70% of patients with primary membranous GN and levels correlate with the clinical course and proteinuria.

Autoantibodies against phospholipase-A2 receptor (PLA2R-Ab), mostly of the IgG4 class, can be found in 70% of patients with primary membranous GN and levels correlate with the clinical course and proteinuria.

Definitive diagnosis is by renal biopsy showing diagnostic findings by light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy.

Definitive diagnosis is by renal biopsy showing diagnostic findings by light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy.

Suggested Reading

Floege J. Primary glomerulonephritis: a review of important recent discoveries. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2013;32(3):103–110.

GLOMERULONEPHRITIS, POSTINFECTIOUS

Definition

Definition

Postinfectious GN (PIGN) occurs after infection, usually with a nephritogenic strain of group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (poststreptococcal GN [PSGN]).

Postinfectious GN (PIGN) occurs after infection, usually with a nephritogenic strain of group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (poststreptococcal GN [PSGN]).

It is the most common glomerular disorder in children between 5 and 15 years.

It is the most common glomerular disorder in children between 5 and 15 years.

Pathogenesis is thought to be related to deposits of immune complexes in the glomerular basement membrane causing glomerular damage. Only 1–2% of cases progress to chronic GN.

Pathogenesis is thought to be related to deposits of immune complexes in the glomerular basement membrane causing glomerular damage. Only 1–2% of cases progress to chronic GN.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Evidence of infection with group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus by throat culture.

Evidence of infection with group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus by throat culture.

Serologic findings: Anti-streptolysin O (ASO) is the most common laboratory test to confirm recent streptococcal infection. ASO titers remain elevated for several months in 50–80% of patients. Anti- DNase B is anther serologic test to confirm a previous group A streptococcal infection.

Serologic findings: Anti-streptolysin O (ASO) is the most common laboratory test to confirm recent streptococcal infection. ASO titers remain elevated for several months in 50–80% of patients. Anti- DNase B is anther serologic test to confirm a previous group A streptococcal infection.

Urinalysis:

Urinalysis:

Hematuria: gross or microscopic. Microscopic hematuria may occur during the initial febrile upper respiratory infection and then reappear with nephritis in 1–2 weeks and lasts for 2–12 months.

Hematuria: gross or microscopic. Microscopic hematuria may occur during the initial febrile upper respiratory infection and then reappear with nephritis in 1–2 weeks and lasts for 2–12 months.

RBC casts and dysmorphic RBCs show glomerular origin of hematuria.

RBC casts and dysmorphic RBCs show glomerular origin of hematuria.

WBC casts and WBCs show inflammatory nature of the lesion.

WBC casts and WBCs show inflammatory nature of the lesion.

Granular and epithelial cell casts are present.

Granular and epithelial cell casts are present.

Fatty casts and lipid droplets occur several weeks later and are not related to hyperlipidemia.

Fatty casts and lipid droplets occur several weeks later and are not related to hyperlipidemia.

Oliguria is frequent.

Oliguria is frequent.

Random urinary protein/creatinine ratio is usually between 0.2 and 2 but may occasionally be in the nephrotic range.

Random urinary protein/creatinine ratio is usually between 0.2 and 2 but may occasionally be in the nephrotic range.

Phenolsulfonphthalein (PSP) excretion is normal in cases of mild to moderate severity and increases with progression of disease. Azotemia with high urine specific gravity and normal PSP excretion usually indicates acute GN.

Phenolsulfonphthalein (PSP) excretion is normal in cases of mild to moderate severity and increases with progression of disease. Azotemia with high urine specific gravity and normal PSP excretion usually indicates acute GN.

Blood Findings:

Blood Findings:

Azotemia is found in approximately 50% of patients.

Azotemia is found in approximately 50% of patients.

Leukocytosis and increased ESR.

Leukocytosis and increased ESR.

There is mild anemia, especially when edema is present (may be caused by hemodilution, bone marrow depression, or increased destruction of RBCs).

There is mild anemia, especially when edema is present (may be caused by hemodilution, bone marrow depression, or increased destruction of RBCs).

Serum proteins are normal, or there is nonspecific decrease in albumin and increase in alpha-2 and sometimes beta and gamma regions.

Serum proteins are normal, or there is nonspecific decrease in albumin and increase in alpha-2 and sometimes beta and gamma regions.

Serum C3 and total hemolytic complement activity (CH50) fall during the active disease and return to normal within 6–8 weeks in 80% of cases. If C3 is low for more than 8 weeks, lupus nephritis or MPGN should be considered.

Serum C3 and total hemolytic complement activity (CH50) fall during the active disease and return to normal within 6–8 weeks in 80% of cases. If C3 is low for more than 8 weeks, lupus nephritis or MPGN should be considered.

Serum cholesterol may be increased.

Serum cholesterol may be increased.

Renal biopsy shows characteristic findings with EM and immunofluorescence microscopy.

Renal biopsy shows characteristic findings with EM and immunofluorescence microscopy.

Chronic renal insufficiency is reported in ≤20% of patients.

Chronic renal insufficiency is reported in ≤20% of patients.

GLOMERULONEPHRITIS, RAPIDLY PROGRESSIVE (CRESCENTIC)

Definition

Definition

Rapidly progressive GN (RPGN) is characterized by progressive loss of renal function and severe oliguria and renal failure that develop over a period of few weeks.

Rapidly progressive GN (RPGN) is characterized by progressive loss of renal function and severe oliguria and renal failure that develop over a period of few weeks.

The histopathologic term “crescentic” refers to crescent formation, a nonspecific response to severe injury to the glomerular capillary wall. Patients may have rapidly progressive GN in association with anti–glomerular membrane (anti-GBM) antibody disease (Goodpasture syndrome), a condition in which circulating antibodies are directed against an antigen in the glomerular basement membrane, resulting in progressive glomerulonephritis and, in approximately 60% of patients, pulmonary hemorrhage. RPGN can also be associated with Wegener granulomatosis, small vessel vasculitis, SLE, or cryoglobulinemia. Depending on the specific disorder, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) can be present in the serum of RPGN patients.

The histopathologic term “crescentic” refers to crescent formation, a nonspecific response to severe injury to the glomerular capillary wall. Patients may have rapidly progressive GN in association with anti–glomerular membrane (anti-GBM) antibody disease (Goodpasture syndrome), a condition in which circulating antibodies are directed against an antigen in the glomerular basement membrane, resulting in progressive glomerulonephritis and, in approximately 60% of patients, pulmonary hemorrhage. RPGN can also be associated with Wegener granulomatosis, small vessel vasculitis, SLE, or cryoglobulinemia. Depending on the specific disorder, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) can be present in the serum of RPGN patients.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Candidates include patients with rapidly developing oliguria or anuria and acute onset of hematuria and edema, especially in the presence of an underlying immunologically mediated systemic illness, or following an infection or administration of certain drugs (e.g., allopurinol, hydralazine, rifampin, D-penicillamine).

Candidates include patients with rapidly developing oliguria or anuria and acute onset of hematuria and edema, especially in the presence of an underlying immunologically mediated systemic illness, or following an infection or administration of certain drugs (e.g., allopurinol, hydralazine, rifampin, D-penicillamine).

Three types of RPGN can be distinguished according to the underlying mechanism of the glomerular injury:

Three types of RPGN can be distinguished according to the underlying mechanism of the glomerular injury:

Type I: mediated by anti-GBM antibodies (<5% of RPGN cases; ≤40 of patients are ANCA positive).

Type I: mediated by anti-GBM antibodies (<5% of RPGN cases; ≤40 of patients are ANCA positive).

Type II: mediated by immune complexes (45% of cases; <5% of patients are ANCA positive).

Type II: mediated by immune complexes (45% of cases; <5% of patients are ANCA positive).

Type III (pauci-immune RPGN): glomerulonephritis is associated with few or no immune deposits by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy (50% of cases; up to 90% of patients are ANCA positive).

Type III (pauci-immune RPGN): glomerulonephritis is associated with few or no immune deposits by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy (50% of cases; up to 90% of patients are ANCA positive).

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory workup is urgent to initiate therapy since untreated patients progress rapidly to ESRD. Renal biopsy findings establish the diagnosis and prognosis.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis

Oliguria, with urine volume often <400 mL/day.

Oliguria, with urine volume often <400 mL/day.

Gross hematuria: RBCs, WBCs, RBC casts.

Gross hematuria: RBCs, WBCs, RBC casts.

Proteinuria starts approximately 3 days after injury and may not be marked because of the severe reduction in GFR.

Proteinuria starts approximately 3 days after injury and may not be marked because of the severe reduction in GFR.

Rapid, progressive rise in creatinine and BUN.

Rapid, progressive rise in creatinine and BUN.

Laboratory tests to determine underlying etiology (e.g., ANCA, anti-GBM antibodies, antinuclear antibodies) can be helpful. Other tests include serology testing for HIV and hepatitis B and C.

Laboratory tests to determine underlying etiology (e.g., ANCA, anti-GBM antibodies, antinuclear antibodies) can be helpful. Other tests include serology testing for HIV and hepatitis B and C.

HEPATORENAL SYNDROME

Definition

Definition

Progressive renal failure that develops in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis or fulminant hepatic failure.

Progressive renal failure that develops in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis or fulminant hepatic failure.

Classified as

Classified as

Type I: serum creatinine increases to >2.5 mg/dL within 2 weeks

Type I: serum creatinine increases to >2.5 mg/dL within 2 weeks

Type II: less severe and associated with gradual increase in serum creatinine (1.5–2.5 mg/dL) over few weeks or months

Type II: less severe and associated with gradual increase in serum creatinine (1.5–2.5 mg/dL) over few weeks or months

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites, especially following fluid loss (e.g., GI hemorrhage, diarrhea or forced diuresis) or an intercurrent infection.

Patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites, especially following fluid loss (e.g., GI hemorrhage, diarrhea or forced diuresis) or an intercurrent infection.

Patients with other liver conditions that are associated with portal hypertension such as severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Patients with other liver conditions that are associated with portal hypertension such as severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Progressive increase in serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL) and decrease in GFR.

Progressive increase in serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL) and decrease in GFR.

No improvement in serum creatinine after volume expansion with intravenous albumin.

No improvement in serum creatinine after volume expansion with intravenous albumin.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis

Oliguria: concentrated urine with high specific gravity

Oliguria: concentrated urine with high specific gravity

Protein excretion <500 mg/day

Protein excretion <500 mg/day

Less than 50 RBCs per high-power field

Less than 50 RBCs per high-power field

Decreased urine sodium (<10 mEq/L)

Decreased urine sodium (<10 mEq/L)

Hyponatremia.

Hyponatremia.

Markedly abnormal liver function tests.

Markedly abnormal liver function tests.

Suggested Reading

Salerno F, Gerbes A, Gines P, et al. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56:1310–1318.

HYPERCALCEMIC NEPHROPATHY

Definition

Definition

This renal condition is caused by increased levels of calcium in the blood due to conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, vitamin D intoxication, milkalkali syndrome, or multiple myeloma or other malignancies.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Increased serum calcium level (12–15 mg/dL).

Increased serum calcium level (12–15 mg/dL).

Decreased urine osmolality due to reduced renal concentrating ability manifested by polyuria and polydipsia.

Decreased urine osmolality due to reduced renal concentrating ability manifested by polyuria and polydipsia.

Proteinuria is usually slight or absent.

Proteinuria is usually slight or absent.

Later findings include decreased GFR, decreased renal blood flow, and azotemia.

Later findings include decreased GFR, decreased renal blood flow, and azotemia.

Renal insufficiency is slowly progressive and may sometimes be reversed by correcting hypercalcemia.

Renal insufficiency is slowly progressive and may sometimes be reversed by correcting hypercalcemia.

HYPERCALCIURIA

See calculi in Chapter 7, Genitourinary System Disorders.

See calculi in Chapter 7, Genitourinary System Disorders.

Hypercalciuria is the most common disorder found in patients with nephrolithiasis (40–50% of cases). It is defined as urinary calcium excretion of >300 mg/day in men and >250 mg/day in women assuming a regular, unrestricted diet. It can also be defined as urinary calcium excretion of >4 mg/kg of body weight per day (for either sex or children) or a urinary concentration of more than 200 mg of calcium per liter.

Hypercalciuria is the most common disorder found in patients with nephrolithiasis (40–50% of cases). It is defined as urinary calcium excretion of >300 mg/day in men and >250 mg/day in women assuming a regular, unrestricted diet. It can also be defined as urinary calcium excretion of >4 mg/kg of body weight per day (for either sex or children) or a urinary concentration of more than 200 mg of calcium per liter.

Types of hypercalciuria:

Types of hypercalciuria:

Renal: due to abnormal renal tubular reabsorption. It is one tenth as common as the absorptive type.

Renal: due to abnormal renal tubular reabsorption. It is one tenth as common as the absorptive type.

Absorptive: due to primary increase in intestinal calcium absorption.

Absorptive: due to primary increase in intestinal calcium absorption.

Resorptive: due to primary hyperparathyroidism.

Resorptive: due to primary hyperparathyroidism.

Idiopathic: the most common cause of hypercalciuria and defined as an excess urinary calcium excretion without an apparent underlying etiology. As a result, diagnosis requires exclusion of all other causes of hypercalciuria. This condition is familial in nature and present in 2–6% of asymptomatic children.

Idiopathic: the most common cause of hypercalciuria and defined as an excess urinary calcium excretion without an apparent underlying etiology. As a result, diagnosis requires exclusion of all other causes of hypercalciuria. This condition is familial in nature and present in 2–6% of asymptomatic children.

Patients with absorptive hypercalciuria will have lowered urine calcium with dietary restriction and therefore can be differentiated from patients with renal or resorptive hypercalciuria.

Patients with absorptive hypercalciuria will have lowered urine calcium with dietary restriction and therefore can be differentiated from patients with renal or resorptive hypercalciuria.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Increased urinary calcium excretion (see definition above) and urinary calcium/creatinine ratio.

Increased urinary calcium excretion (see definition above) and urinary calcium/creatinine ratio.

Blood calcium level is typically normal. Other laboratory tests such as serum creatinine, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and vitamin D levels help identify the cause of hypercalciuria.

Blood calcium level is typically normal. Other laboratory tests such as serum creatinine, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and vitamin D levels help identify the cause of hypercalciuria.

HYPERTENSIVE NEPHROSCLEROSIS

Definition

Definition

This condition is characterized by thickening and luminal narrowing of the large and small arteries and arterioles of the kidney and sclerosis of the glomeruli secondary to hypertension.

This condition is characterized by thickening and luminal narrowing of the large and small arteries and arterioles of the kidney and sclerosis of the glomeruli secondary to hypertension.

It is classified as benign or malignant (rare) depending the severity of hypertension and rapidity of the arteriolar change. With the malignant form, severe high blood pressure can lead to acute kidney injury and hematuria.

It is classified as benign or malignant (rare) depending the severity of hypertension and rapidity of the arteriolar change. With the malignant form, severe high blood pressure can lead to acute kidney injury and hematuria.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Patients with long history of hypertension presenting with slowly progressive elevations in serum BUN and creatinine levels and mild proteinuria.

Patients with long history of hypertension presenting with slowly progressive elevations in serum BUN and creatinine levels and mild proteinuria.

Blacks, patients with marked elevations of blood pressure, and patients with diabetic nephropathy are at higher risk.

Blacks, patients with marked elevations of blood pressure, and patients with diabetic nephropathy are at higher risk.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Benign nephrosclerosis: elevated BUN and creatinine, mild proteinuria (usually <1 g/day), and normal or near-normal urine sediment.

Benign nephrosclerosis: elevated BUN and creatinine, mild proteinuria (usually <1 g/day), and normal or near-normal urine sediment.

Malignant nephrosclerosis: hematuria, azotemia, and proteinuria (minimal or marked).

Malignant nephrosclerosis: hematuria, azotemia, and proteinuria (minimal or marked).

Renal biopsy is rarely indicated; diagnosis is mainly based on the clinical features.

Renal biopsy is rarely indicated; diagnosis is mainly based on the clinical features.

IgA NEPHROPATHY

Definition

Definition

This immune-mediated condition, also referred to as Berger disease, is the most common cause of glomerulonephritis and the primary chronic glomerular disease worldwide. It is characterized by prominent deposition of IgA in the glomerular mesangium.

This immune-mediated condition, also referred to as Berger disease, is the most common cause of glomerulonephritis and the primary chronic glomerular disease worldwide. It is characterized by prominent deposition of IgA in the glomerular mesangium.

Progressive decline in renal function occurs in approximately 40% of cases; half of these reach ESRD in 5–25 years. Up to 30% of cases have a benign course with persistent microscopic hematuria.

Progressive decline in renal function occurs in approximately 40% of cases; half of these reach ESRD in 5–25 years. Up to 30% of cases have a benign course with persistent microscopic hematuria.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Who Should Be Suspected?

Presenting conditions may include persistent or intermittent hematuria (visible or microscopic) that can be associated with proteinuria. Episodes of visible hematuria occur in 75% of children and young adult cases and often start few days following upper respiratory infection.

Presenting conditions may include persistent or intermittent hematuria (visible or microscopic) that can be associated with proteinuria. Episodes of visible hematuria occur in 75% of children and young adult cases and often start few days following upper respiratory infection.

Few cases (<10%) can have a more severe presentation that is similar to nephrotic syndrome or rapidly progressive GN (edema, renal insufficiency, and hematuria).

Few cases (<10%) can have a more severe presentation that is similar to nephrotic syndrome or rapidly progressive GN (edema, renal insufficiency, and hematuria).

IgA deposits are frequently associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (IgA vasculitis) and may also be found with diseases of the GI tract (e.g., celiac disease), skin (e.g., dermatitis herpetiformis), liver (e.g., cirrhosis), carcinomas (e.g., lung, pancreas), autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE, RA), and infections (e.g., HIV, leprosy).

IgA deposits are frequently associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (IgA vasculitis) and may also be found with diseases of the GI tract (e.g., celiac disease), skin (e.g., dermatitis herpetiformis), liver (e.g., cirrhosis), carcinomas (e.g., lung, pancreas), autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE, RA), and infections (e.g., HIV, leprosy).

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory Findings

Diagnosis is based on renal biopsy finding by immunofluorescence microscopy showing predominant mesangial IgA deposits alone or with IgG, IgM, or both. Complement C3 and properdin are almost always present, and C1q is usually absent.

Diagnosis is based on renal biopsy finding by immunofluorescence microscopy showing predominant mesangial IgA deposits alone or with IgG, IgM, or both. Complement C3 and properdin are almost always present, and C1q is usually absent.

Urinalysis shows RBCs and RBC urinary casts.

Urinalysis shows RBCs and RBC urinary casts.

Proteinuria is usually <2 g/day.

Proteinuria is usually <2 g/day.

Serum IgA level is increased in ≤50% of patients.

Serum IgA level is increased in ≤50% of patients.

Serum complement is normal.

Serum complement is normal.

Serum galactose-deficient IgA1 concentration is frequently elevated.

Serum galactose-deficient IgA1 concentration is frequently elevated.

Serum levels of glycan-specific IgG antibodies have been found to correlate with urinary protein excretion and risk of progression to ESRD or death.

Serum levels of glycan-specific IgG antibodies have been found to correlate with urinary protein excretion and risk of progression to ESRD or death.

Suggested Reading

Wyatt RJ, Julian BA. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2402–2414.

INTERSTITIAL NEPHRITIS

Definition

Definition

This immune-mediated condition is characterized by the presence of inflammatory infiltrate in the kidney interstitium. The onset can be acute or chronic.

This immune-mediated condition is characterized by the presence of inflammatory infiltrate in the kidney interstitium. The onset can be acute or chronic.

Drug therapy is responsible for more than 75% of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) cases. The major causative drugs include antibiotics (e.g., beta lactams, cephalosporins, rifampin), sulfonamide diuretics, and NSAIDs.

Drug therapy is responsible for more than 75% of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) cases. The major causative drugs include antibiotics (e.g., beta lactams, cephalosporins, rifampin), sulfonamide diuretics, and NSAIDs.

Other causes include

Other causes include

Infections (5–10% of cases): group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infections, diphtheria, brucellosis, leptospirosis, infectious mononucleosis, toxoplasmosis

Infections (5–10% of cases): group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infections, diphtheria, brucellosis, leptospirosis, infectious mononucleosis, toxoplasmosis

Systemic diseases (10–15% of cases): SLE, Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis

Systemic diseases (10–15% of cases): SLE, Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU syndrome)

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU syndrome)

Toxic substances

Toxic substances

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree