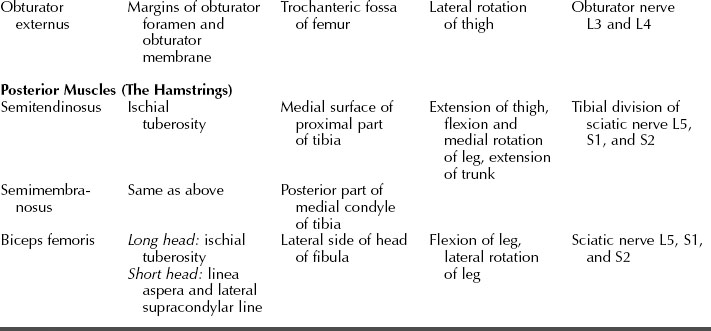

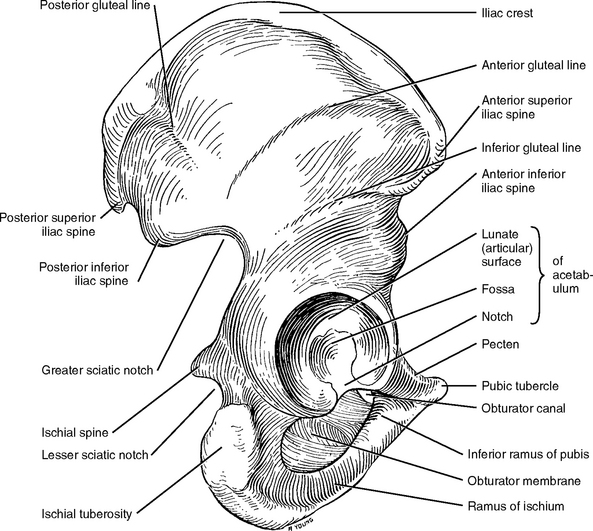

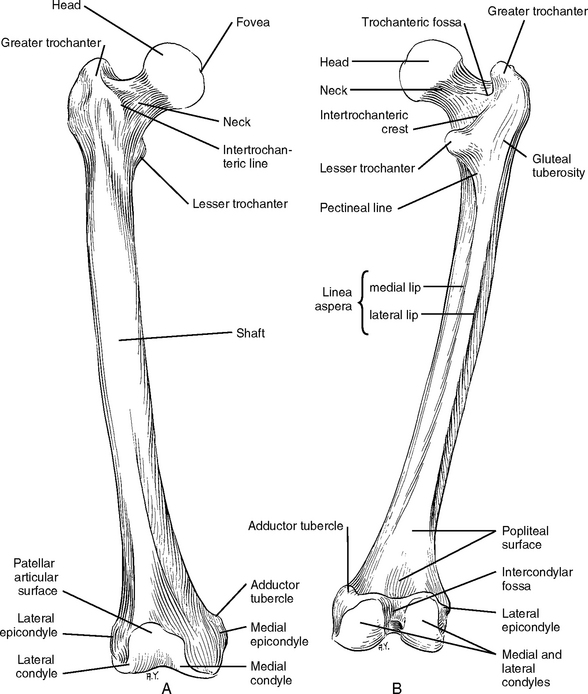

CHAPTER 11 Lower Limb Pain: Hip, Thigh, Knee, Leg, Ankle, and Foot

INTRODUCTION

The lower limb consists of four major parts:

It is important to stress again that acupuncture practitioners must treat the whole body, not only the local symptoms. When treating the lower limb, a practitioner must examine the lower back. If there are tender points in the lower back, a practitioner must examine the upper back and the neck. This is why it is so important for an acupuncture practitioner to understand basic anatomy as it relates to acupuncture therapy and why so many chapters in this book emphasize anatomical descriptions from this standpoint.

BASIC ANATOMY OF THE LOWER LIMB: ITS RELATION TO PAIN AND ACUPUNCTURE THERAPY

The Bones of the Lower Limb

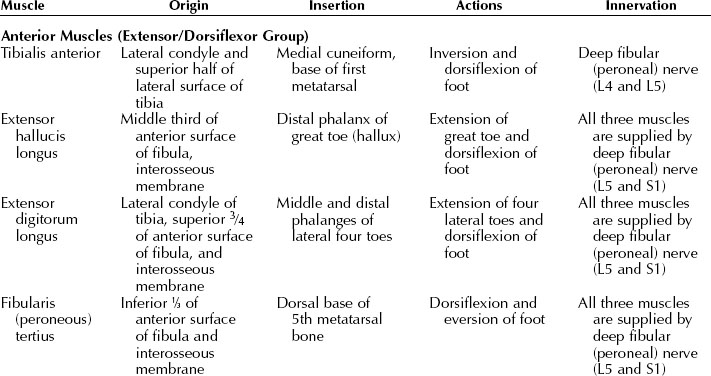

The large, irregular hip bone (os coxae) is composed of three bones: ilium, ischium, and pubis. These bones begin to fuse at 15 to 17 years of age and the fusion is complete by age 23. Thus, the hip bone is indistinguishably joined in an adult (Figure 11-1). A cup-shaped socket (named acetabulum, after a shallow cup used in ancient Rome for vinegar) is formed where the three bones fuse. The acetabulum and head of the femur form the hip joint.

Figure 11-1 Hip bone and its articular surfaces. Lateral view.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 264.)

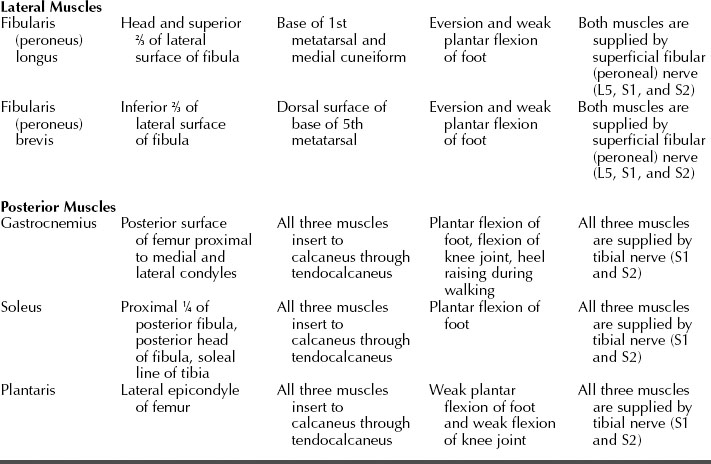

The femur is the longest, strongest, and heaviest bone in the body (Figure 11-2). A person’s height is about four times the length of the femur. The femur consists of a rounded head, neck, and greater and lesser trochanters at the proximal portion of the shaft, and two broadened lateral and medial condyles at the distal portion. The two condyles articulate with the tibia and patella to form the knee joint.

Figure 11-2 Anterior (A) and posterior (B) views of the femur.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 269.)

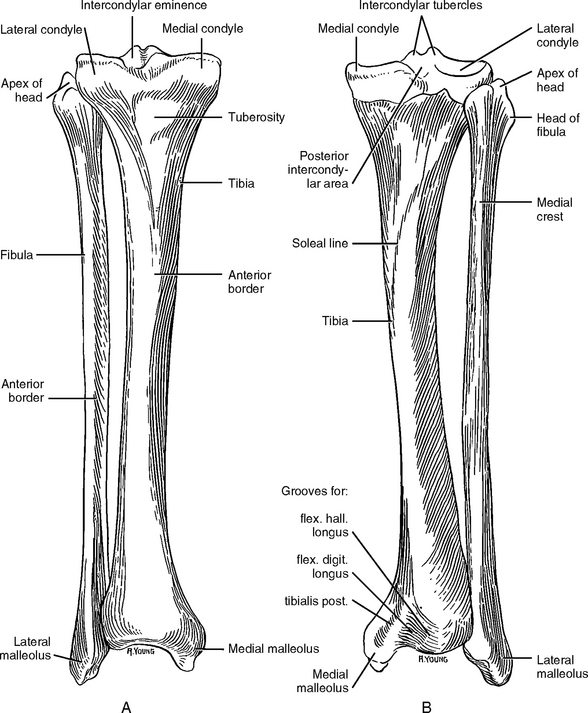

The leg consists of two bones, the tibia (shin bone) and the fibula (splint bone, calf bone). The tibia is the second largest bone in the body and is located on the anteromedial side of the leg. The tibia supports most of the body weight. The proximal end of the tibia is large and its lateral and medial condyles articulate with the corresponding condyles of the femur. The patellar ligament from the thigh muscles inserts into the prominent tibial tuberosity. The distal end of the tibia is small and has articular surfaces for the fibula and talus (Figure 11-3). Here the tibia forms the medial malleolus to stabilize the ankle. The shaft of the tibia is triangular in cross section.

Figure 11-3 Anterior (A) and posterior (B) views of the right tibia and fibula.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 329.)

The fibula is a long, pinlike bone (fibula means “pin” in Latin) that articulates with the tibia posterolateral. The fibula serves mainly as an attachment for muscles and gives stability to the ankle joint. The proximal end of the fibula is its head, which has a facet to articulate with the inferior surface of the lateral tibial condyle. The distal end of the fibula is the lateral malleolus, which helps to hold the talus in its socket (see Figure 11-3).

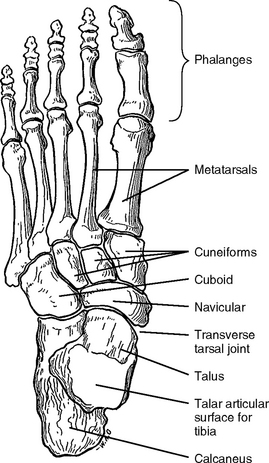

The foot consists of 7 tarsal bones, 5 metatarsal bones, and 14 phalanges (Figure 11-4). Of the seven tarsal bones, only the talus articulates with the leg bones. When treating ankle and foot pain, the practitioner needs to understand the anatomy and biomechanics of the foot to know where to find the symptomatic acupoint(s) (SAs). This chapter will focus only on cases that are commonly seen in acupuncture clinics, such as ankle sprain and plantar fasciitis, and will therefore not describe the complete anatomy and biomechanics of the foot, although readers may consult the available professional literature for more detailed knowledge.

Muscles

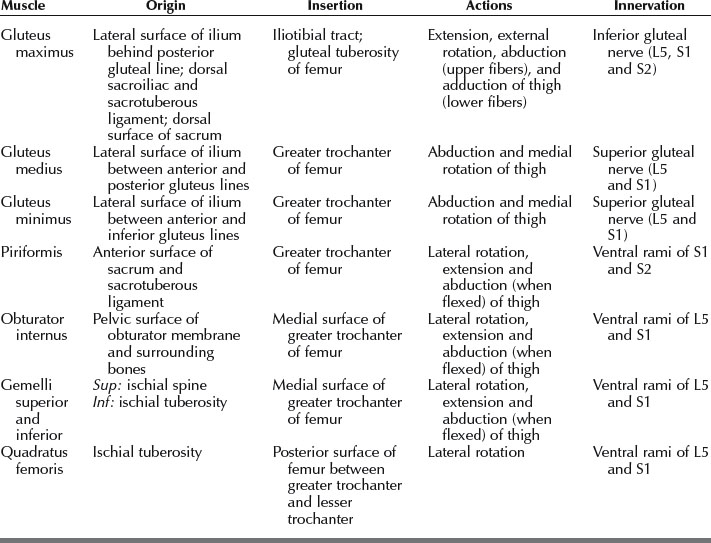

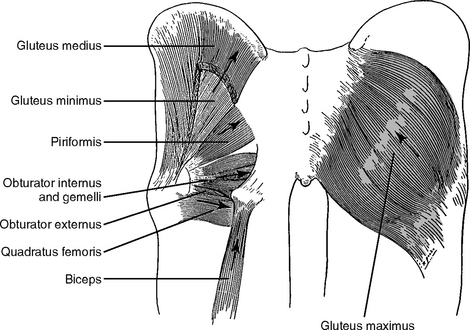

The Gluteal Muscles

The gluteal muscles include (1) the three large glutei (gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus) and (2) four deeper small muscles (piriformis, obturator internus, gemelli, and quadratus femoris) (Figure 11-5). The three large glutei are extensors and abductors of the thigh at the hip joint and they also stabilize the pelvis. The small muscles are lateral rotators of the thigh at the hip joint and stabilize the femoral head in the acetabulum. Table 11-1 shows a summary of the muscles of the gluteal region.

Figure 11-5 The gluteal muscles.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 316.)

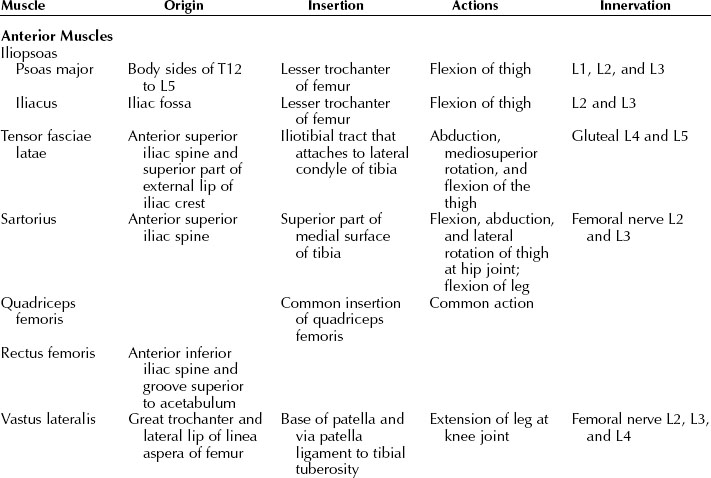

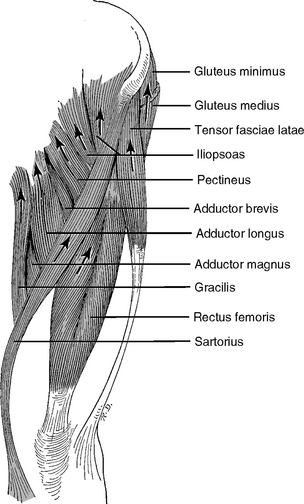

The Anterior Thigh Muscles (Flexor Group)

The major muscles of the anterior group are iliopsoas, tensor fasciae latae, sartorius, and quadriceps femoris (Figure 11-6). They are accessible to acupuncture needling. Their anatomic function is summarized in Table 11-2.

Figure 11-6 Anterior thigh muscles (flexors).

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 317.)

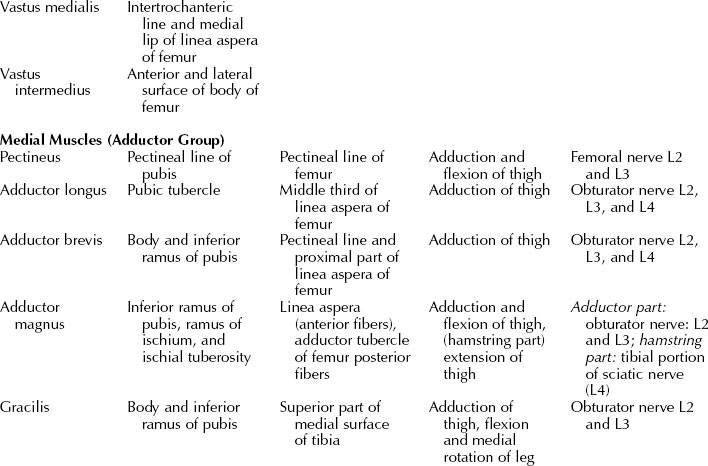

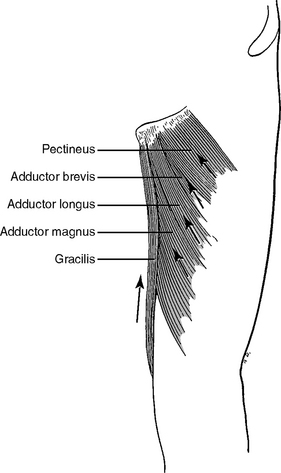

The Medial Thigh Muscles (Adductor Group)

The medial thigh muscles (the pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, and obturator externus) are adductors of the thigh (Figure 11-7). All of these muscles are supplied by the obturator nerve (L2, L3, and L4) except pectineus, which is supplied by the femoral nerve (L2 and L3). The “hamstring” part of the adductor magnus is supplied by the sciatic nerve (L4).

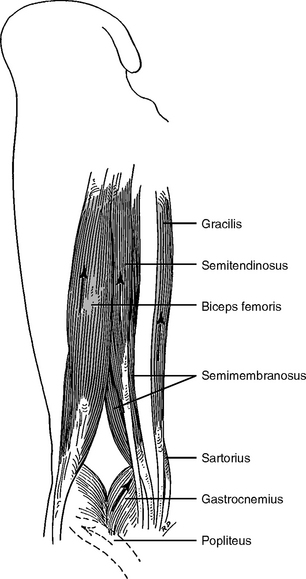

The Posterior Thigh Muscles (The Hamstrings)

Three large muscles (semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris) of the posterior aspect are collectively known as the hamstring muscles (Figure 11-8). These muscles have the same origin on the ischial tuberosity, but the short head of the biceps femoris has an additional origin on the shaft of the femur. These long muscles extend from the hip joint and across the knee joint so they are all extensors of the thigh and flexors of the leg. In addition, they are all supplied by the same sciatic nerve.

Figure 11-8 The hamstrings: the flexors of the leg.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 320.)

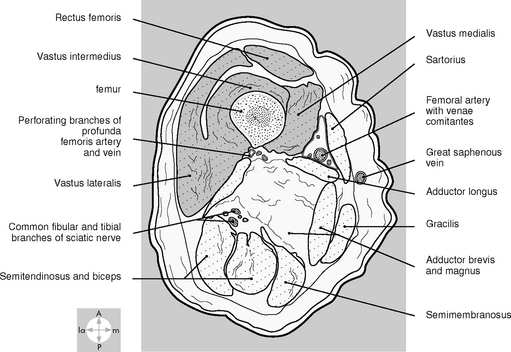

The topography of the three groups of thigh muscles is shown in Figure 11-9.

The Leg Muscles

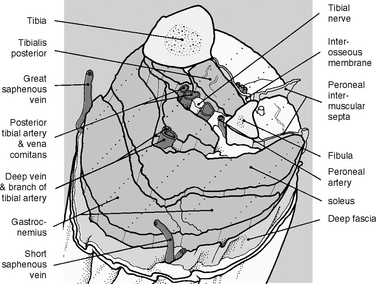

Anatomically and functionally the leg muscles are divided into three compartments by (1) the tibia, the fibula, and the interosseous membrane between them and (2) the anterior and posterior crural intermuscular septa (Figure 11-10): the anterior, lateral, and posterior. The muscles in the same compartment perform similar functions and share the same nerve and blood supply.

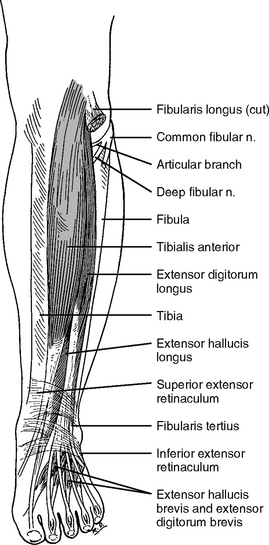

The anterior compartment is between the tibia and the anterior crural septum. The muscles of this compartment function as extensors of the toes and effect dorsiflexion of the ankle joint (Figure 11-11).

Figure 11-11 The anterior muscles of the leg.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 339.)

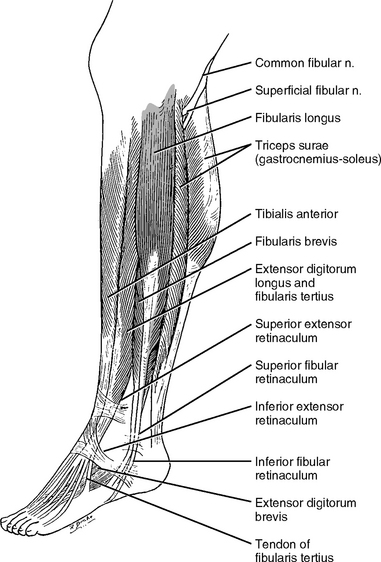

The lateral compartment is surrounded by the lateral aspect of the fibula and anterior and posterior crural intermuscular septa. The two muscles in this compartment are responsible for plantar flexion and eversion of the foot (Figure 11-12).

Figure 11-12 The lateral muscles of the leg.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 338.)

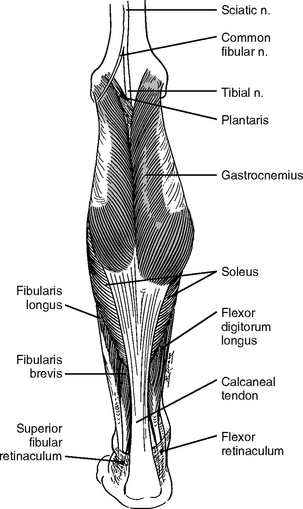

The posterior compartment contains both superficial and deep muscles (Figure 11-13). The three powerful superficial calf muscles affect plantar flexion of the foot. These large muscles support and move the weight of the body. Four smaller deep muscles of the posterior compartment act on the knee joint (popliteus) and ankle and foot joints. These four smaller muscles are not important in acupuncture therapy and therefore are not listed in Table 11-3.

Figure 11-13 The posterior muscles of the leg.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 333.)

Nerves of Clinical Importance

The Superior Cluneal Nerves

The superior cluneal nerves are branches of the dorsal rami of L1, L2, and L3. They emerge from the deep fascia just superior to the iliac crest and innervate the skin on the superior two thirds of the gluteal region (buttocks). An important homeostatic acupoint, H14 superior cluneal, is formed at the location where the nerves penetrate the deep fascia. Most patients feel tenderness or even pain upon palpation at H14. In patients with chronic lower back or leg pain, the pain may spread over the entire skin area that is supplied by the superior cluneal nerves. In such cases, H14 and adjacent areas should be needled together.

The Inferior Gluteal Nerve

The Sciatic Nerve and Its Terminal Branches: the Tibial, Common Fibular (Peroneal), and Sural Nerves

We have discussed this nerve in Chapter 5 and here we emphasize its relation to HAs and pain in the lower limb. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body. The ventral rami of L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3 converge at the inferior border of the piriformis muscle to form the sciatic nerve (Figure 11-14). Structurally the sciatic nerve consists of two nerves: the tibial and the common fibular (peroneal) nerve. The sciatic nerve leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen of the hip bone and enters the gluteal region inferior to the piriformis muscle (Figure 11-15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree