10 CASE 10

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF KEY SYMPTOMS

The mitral valve usually closes and isolates the left atrium from the left ventricle during ventricular systole. In patients with mitral valve regurgitation the high pressures generated during left ventricular systole lead to the ejection of blood into the aorta (normal) as well as the backward flow of blood from the left ventricle into the left atrium (abnormal). Retrograde blood flow through the mitral valve is turbulent and can be heard as a systolic murmur (see Fig. 9-1, p.30 in Case 9).

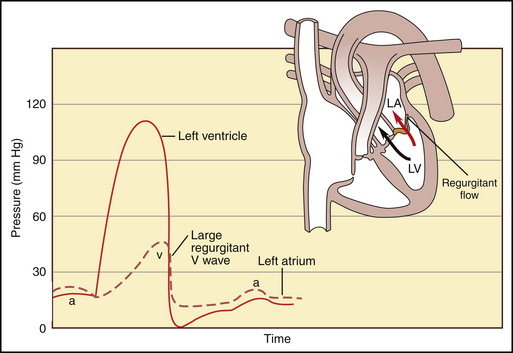

Normal functioning of the cardiac valves is essential to the pumping ability of the heart. Normally, the left ventricular and diastolic volume is about 150 mL and 60% of this volume is ejected into the aorta during ventricular systole (60% ejection fraction) and 40% remains in the left ventricle as the end-systolic left ventricular volume. In this patient, blood in the left ventricle at the end of diastole can (1) be pumped into the aorta, (2) be pumped retrograde back into the left atrium, or (3) remain in the left ventricle. The ejection fraction is reduced because of the retrograde flow of blood through the mitral valve. In addition, the left atrium now has two sources of filling: the normal filling of blood flowing from the pulmonary vein and the retrograde filling of blood flowing from the left ventricle during ventricular systole. Consequently, the left atrium is enlarged and left atrial pressures are elevated (Fig. 10-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree