CHAPTER 1 Fundamental Concepts

WHY USE HERBAL LIQUIDS?

TASTE ISSUE

Contact time can be further reduced by immediately rinsing the mouth with water or fruit juice. Approximately 50 ml should be quickly consumed immediately after the liquid is taken. To best achieve this effect, the diluted liquid should be in one hand and the rinse in the other. The two liquids are then consumed in a one-two action, as quickly as possible. Using this technique, taste can be dramatically minimized, and few patients complain of any problem. For herbs with a lingering aftertaste, eating something afterwards will help.

HOW HERBAL LIQUIDS ARE MADE

Some of the factors involved in the preparation of herbal liquids are useful to consider in detail.

SOLVENT USED

A number of studies have highlighted the importance of the correct choice of the ethanol percentage in terms of maximizing the quality of herbal liquid preparations. A Swiss study found that 55% ethanol was the optimum percentage for the extraction of the essential oil from chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla).1 Higher percentages of ethanol did not extract any additional oil, and the solids content of the extract was decreased, indicating that other components were being less efficiently extracted. More recently, Meier found that 40% to 60% ethanol was the optimum range for achieving the highest extraction efficiency for the active components of a variety of herbs.2 For example, at 25% ethanol, none of the saponins in ivy leaves (Hedera helix) were extracted, but at 60% ethanol, they were maximally extracted. Similarly, the alkylamides, which give the oral tingling sensation from Echinacea, are better extracted at higher ethanol percentages. Extracts of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) prepared in 25% ethanol will not contain any silymarin because it is insoluble at this concentration.

Higher ethanol percentages do not always confer higher activity. French researchers found that Viburnum prunifolium bark extracted at 30% ethanol was five times more spasmolytic compared with a 60% extract.3

Glycetracts or glycerites are herbal liquid preparations made using glycerol and water instead of ethanol and water. Glycetracts are useful preparations when the active components are water soluble, for example, marshmallow root (Althaea officinalis), because they do not contain alcohol, and the sweetness of the glycerol gives them a better taste. However, the importance of these preparations should not be overrated. Glycerol is a poor solvent for many of the active components found in herbs, and glycetracts are less stable compared with alcoholic extracts (see the later discussion). Moreover, because of the viscosity of glycerol, concentrated preparations are difficult to make by percolation. The manufacture of 1:1 or 1:2 glycetracts therefore invariably requires the use of a concentration step involving the application of heat or vacuum, which risks deterioration of the product.

Herbal liquid preparations based on alcohol can exhibit superior bioavailability. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study on children with chronic obstructed airways were reported in the “Industry News” section of the Zeitschrift für Phytotherapie.4 The therapeutic effects of ethanolic and ethanol-free galenical extracts of ivy leaves (Hedera helix) were compared. Spirometric testing showed a significant improvement in lung function for both products, which was superior to conventional bronchodilators. However, results indicated that the addition of alcohol to the preparation yielded an increase in the bioavailability of active components. The dose of the alcohol-free preparation needed to be adjusted to a higher level to obtain the same effect.

GLYCEROL-WATER COMBINATIONS

Recently, glycerol-water preparations have become popular, resulting from some perceived disadvantages of ethanol-water combinations (see the previous discussion). A less important reason in real terms is that glycerol is seen to be less toxic than is ethanol. However, glycerol is chemically classified as an alcohol and is also toxic at high levels. The 26th edition of Martindale’s Extra Pharmacopoeia states that large doses of glycerol by mouth can exert systemic effects such as headache, thirst, and nausea. The injection of large doses may induce convulsions, paralysis, and hemolysis. A 2.6% solution of glycerol will cause 100% hemolysis of red blood cells. Glycerol has an irritant effect on the gastric mucosa when given at concentrations greater than 40%, and large oral doses of glycerol caused signs that were misdiagnosed as cardiac arrest in one elderly patient with hypertension.5 The authors concluded that these elderly patients were liable to be dehydrated and that the effects from glycerol ingestion on an empty stomach may be acute.5

MACERATION

WHY ARE 1:2 HERBAL LIQUIDS GENERALLY RECOMMENDED?

The argument holds that 1:2 extracts are relatively new, are not mentioned in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia 1983 (BHP) or other pharmacopeias, and therefore should not be used. In fact, 1:2 extracts are mentioned in nineteenth century texts6,7 and are described in the seventh edition of the German pharmacopeia (Deutsches Arzneibuch [DAB], published in 1968).8 The seventh edition of the DAB actually defines a liquid extract as a 1:2 extract.9 Therefore the precedent for their use is ample.

FRESH PLANT TINCTURES

On the other hand, the following observations need to be considered:

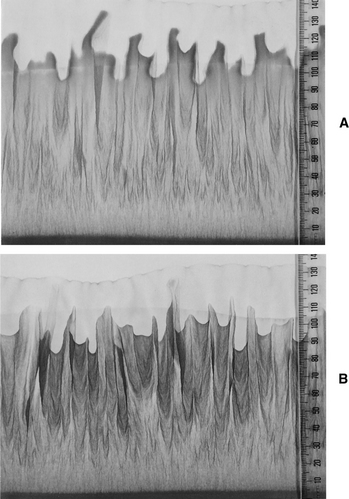

Dried plant preparations made in such a way will still preserve the “vitality” or “energy” of the original plant, which is embodied in its chemical complexity. Fig. 1-1 gives a visual comparison of a dried plant extract (A) with a fresh plant tincture (B) using a paper chromatography technique known as vertical capillary dynamolysis. Adherents to the anthroposophy movement believe this technique can demonstrate the “vitality” of a preparation under test. Although the analysis of the chromatograms is subjective, the figure does show that a “vitality” to dried plant extracts exists.

GALENICAL EXTRACTS AND THE CONCEPT OF SYNERGY

The main reason why herbalists prefer “whole” or galenical extracts is their belief that the active component is the herb itself. In other words, all of the phytochemicals in the plant act together to confer the therapeutic benefit. According to Sharma:11

An excellent discussion of synergy in the context of herbal therapy was provided by E. M. Williamson.12 According to the author, “It is almost inescapable that these interactions between ingredients will occur; however, whether the effects are truly synergistic or merely additive is open to question…” In other words, the more likely interaction between the components of a galenical extract is an addition of their pharmacologic effects, rather than true synergy. Even in this case, the “whole” will still be better than a selection of the parts.

As previously inferred, one area in which synergistic interactions probably apply is that of the enhanced bioavailability of key components. Eder and Mehnert discussed the basic issues, and examples can be found in the scientific literature.13 The isoflavone glycoside daidzin given in crude extract of Pueraria lobata achieves much greater concentrations in plasma than does equivalent doses of pure daidzin.14 Ascorbic acid in a citrus extract was more bioavailable than was ascorbic acid alone.15 Coadministration of procyanidins from Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) significantly increased the in vivo antidepressant effects of hypericin and pseudohypericin. This effect was attributed to the observed enhanced solubility of hypericin and pseudohypericin in the presence of procyanidins. The result also indicates that pure hypericin and pseudohypericin have considerably less antidepressant activity than do their equivalent amounts in St. John’s wort extract.16

However, synergy can also have a pharmacodynamic basis. One example is the antibacterial activity of major components of lemon grass essential oil. Although geranial and neral individually elicit antibacterial action, the third main component, myrcene, did not show any activity. However, myrcene enhanced antibacterial activities when mixed with either of the other two main components.17 Sennoside A and sennoside C from senna have similar laxative activities in mice. However, a mixture of these compounds in the ratio 7:3 (which somewhat reflects the relative levels found in senna leaf) has almost double the laxative activity.18

Additional examples of synergy for galenical extracts are provided by Williamson and include kava, valerian, dragon’s blood, and Artemisia annua.12