1 CASE 1

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

LABORATORY STUDIES

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF KEY SYMPTOMS

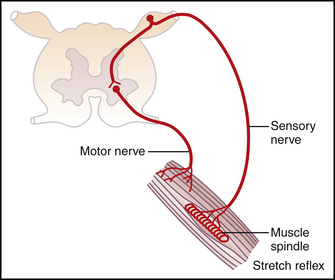

An appropriate patellar tendon reflex requires afferent input from the muscle spindles, transmission of the afferent action potential to the spinal cord, a monosynaptic reflex within the spinal cord, efferent action potential transmission by the alpha (α)-motor neuron, transmission across the neuromuscular synapse, activation of the skeletal muscle, and, finally, contraction (Fig. 1-1). This patient shows a hyperreflexive response in the right leg. Normally, the α-motor neurons receive descending inhibitory input from upper motor neurons and both inhibitory and stimulatory input from interneurons (Figs. 1-2 and 1-3). Hyperreflexia can be an indication that the normal descending input is diminished, which is characteristic of an upper motor neuron disease.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree