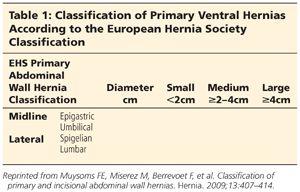

■ Primary ventral hernias are classified according to the diameter of the hernia defect as shown in Table 1.2

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Subcutaneous lesions at the site where primary ventral hernias occur, like lipoma, sebaceous cysts, metastatic lesions, and trocar site metastasis.

■ Caveat: Epigastric lipoma: In a patient with a clinical subcutaneous lipoma near the midline above the umbilicus, an epigastric hernia should always be suspected.

■ Abdominal wall tumors: desmoid tumors (or fibromatosis), soft tissue sarcoma, metastatic lesions.

■ Caveat: A “Sister Joseph’s nodule” is an umbilical swelling that might be mistaken for an umbilical hernia but is the manifestation of intraperitoneal carcinomatosis.

■ Secondary ventral hernias: incisional hernia, trocar site hernia, and recurrent ventral hernias after previous repair.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Symptoms can range from an asymptomatic presentation to acute incarceration with bowel obstruction and/or strangulation.

■ Many small umbilical or epigastric hernias are asymptomatic, and often, the patient is not even aware of having a small abdominal wall defect.

■ A swelling at the hernia site is often the first sign of a hernia. This swelling is usually present for a long time period and gradually increases in size (FIG 2).

■ The presence of a reducible swelling, enlarging when straining (Valsalva maneuver), is pathognomonic for an abdominal wall hernia, but not all hernias are reducible and can hinder the clinical diagnosis in those hernias.

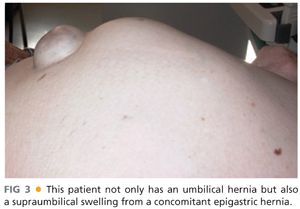

■ The swelling of an epigastric hernia is often mistaken for a subcutaneous lipoma (FIG 3).

■ Pain intensity is not always correlated with the size of the hernia defect. Small hernias can cause a sharp pain, whereas umbilical hernias can be quite large without significant pain. The pain is caused by herniation of abdominal contents or of preperitoneal fat through the defect.

■ For some hernias that are not palpable, such as spigelian hernias, abdominal wall pain can be the first presenting symptom and diagnosis might only be possible by imaging.

■ Acute pain due to incarceration of intestines or omentum is very intense and sharp. Incarceration can be intermittent and resolve by lying down and manual compression of the hernia sac. Reduction of an incarcerated hernia allows the patient to be operated on electively after appropriate preoperative workup. If manual reduction is not possible, an emergency operation to reduce the hernia is indicated.

■ Intestinal obstruction and vomiting due to incarcerated small bowel sometimes is the primary presentation in patients who have a subclinical hernia. In obese patients and for spigelian or lumbar hernias, the incarcerated hernia is sometimes not clinically visible or palpable.

■ Late presentation of an incarcerated hernia includes sepsis from bowel ischemia and intestinal perforation. This can evolve into peritonitis or enterocutaneous fistula.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ For diagnosis of an umbilical or epigastric hernia, clinical examination is sufficient for the majority of patients. Imaging is rarely needed for most patients.

■ Imaging with ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan can be helpful to measure the hernia defect size in irreducible hernias or obese patients. Sometimes the size of the hernia defect will influence the therapeutic approach, for example, open or laparoscopic technique.

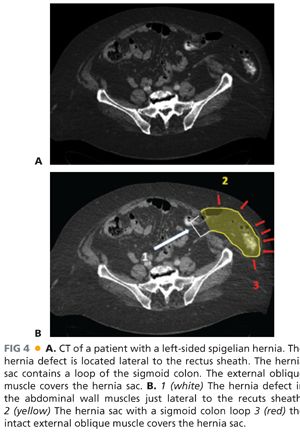

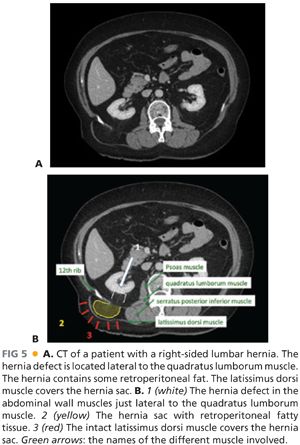

■ For spigelian and lumbar hernias, imaging with ultrasound or CT scan is often needed to make the diagnosis: spigelian hernia (FIG 4), lumbar hernia (FIG 5).

■ CT scan imaging of the abdominal wall allows sizing the defect to see the hernia sac contents and to detect signs of intestinal obstruction.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ Small primary umbilical, epigastric, or lumbar hernias do not require an operation, unless they are painful, increase in size, or cosmetic considerations are present. For spigelian hernias, a surgical repair is indicated even for asymptomatic patients because they hold an increased risk of incarceration compared to the other primary ventral hernias.

■ There is no consensus whether a suture repair for small primary hernias is sufficient or if every primary ventral hernia should be treated by mesh reinforcement.3 For inguinal hernias and incisional hernias, the current recommendation is to use mesh in all patients because of the proven decrease in recurrences. Therefore, recurrent umbilical or epigastric hernias should be repaired using a mesh prosthesis, as they are considered to be incisional hernias. Most surgeons agree that only small (<2 cm) primary ventral hernias should be repaired without mesh reinforcement.

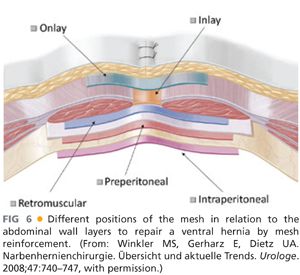

■ The mesh used to repair abdominal wall hernias can be placed at different positions in relation to the abdominal wall layers. Five positions can be defined: onlay, inlay, retromuscular, preperitoneal, and intraperitoneal (FIG 6).1

■ Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias is a technique with promising short-term results.4 The technique is safe but long-term follow-up is needed in order to elucidate whether laparoscopic repair of ventral hernia is efficacious.4

Preoperative Planning

■ Based on the size and the localization of the hernia, a decision will be made about the preferred approach in the individual patient: mesh or primary repair/open or laparoscopic technique.

■ Although some centers perform the repair of small umbilical or epigastric hernias under local anesthesia as a routine, most centers prefer a general anesthesia for the comfort of the patient and the surgeon. Regional anesthesia through a sensory blocking of the anterior abdominal wall, by a transversus abdominis plane block (TAP block), is another less practiced option for postoperative pain control.

■ For incarcerated hernias with bowel obstruction, adequate preoperative measures with nasogastric tube suction and rapid “sequence intubation” should be considered to minimize aspiration risk.

■ Preoperative cleaning and disinfection of the umbilicus is helpful in decreasing the bacterial load during the operation.

■ Antibiotic prophylaxis as a routine is not indicated for most hernia repairs because they are clean operations with a low risk of wound infection. In the presence of risk factors for wound infection, antibiotic prophylaxis at induction of anesthesia should be considered.

Positioning

■ Patients treated for primary ventral hernias are usually positioned in a dorsal decubitus. Lumbar hernias are positioned in a 90-degree or 45-degree lateral decubitus to expose the lumbar region (FIG 7).

■ For laparoscopic approach of ventral hernias, the position of the surgeon and the video equipment is determined by the localization of the hernia. It is important to have a wide lateral accessibility of the abdominal wall, because the trocars are placed very laterally to obtain access to hernias on the midline.

TECHNIQUES

SUTURE REPAIR

Incision

■ For umbilical hernias, the incision of the skin for primary repair can be within the umbilical rim, thus leaving a nearly invisible scar postoperatively. The incision can be placed either cranial or caudal, depending on the site of the hernia sac. It is recommended not to incise the umbilical rim for more than 180 degrees because of the increased risk of devascularization of the umbilical skin after further dissection of the hernia sac, leading to skin necrosis and wound infection.

■ For epigastric, spigelian, or lumbar hernias, the incision will be directly above the hernia.

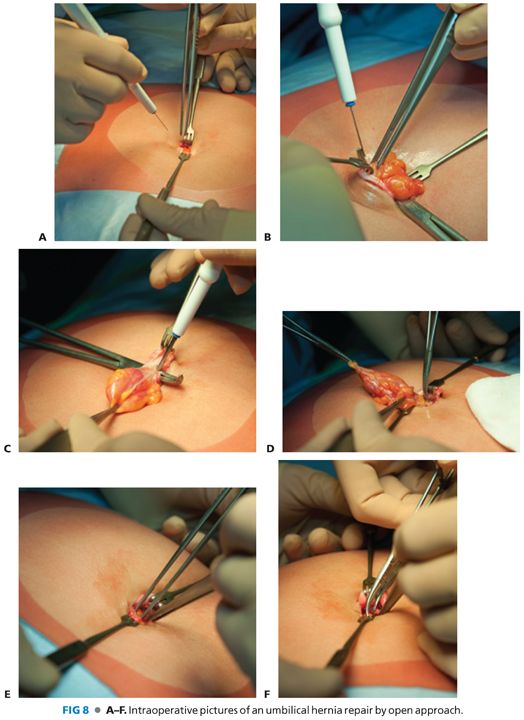

■ The skin is retracted with small Volkmann retractors and the subcutaneous layer incised down to the fascia, exposing one side, cranial or caudal of the hernia defect (FIG 8A).

Dissection of the Hernia Sac

■ Starting at the lateral side of the hernia defect, the hernia sac, usually containing preperitoneal fat and/or omentum, is encircled using a curved hemostat clamp. The clamp is pushed through to the other side of the hernia defect (FIG 8B).

■ The top of the hernia sac is dissected of the umbilical skin, taking care not to injure the skin (FIG 8C). This will expose the opposite side of the hernia defect (FIG 8D).

Reduction of the Hernia Sac

■ The hernia sac and its contents are reduced through the hernia defect behind the abdominal wall muscles (FIG 8E). Careful control of hemostasis of the preperitoneal region is performed.

■ Sometimes, the contents of the hernia sac are too voluminous to be reduced through the hernia defect. This is often the case in umbilical hernias with herniation of omental fatty tissue and in epigastric hernias with preperitoneal fat. In these patients, we can either resect the herniated fatty tissue or we can enlarge the hernia defect.

■ In patients with acute incarcerated hernias, the hernia sac should be opened and the herniated bowel inspected for viability. In case of doubt, a bowel resection should be considered.

Closure of the Hernia Defect by Primary Closure

■ The fascial edges of the defect are identified and isolated from the subcutaneous tissue and from the preperitoneal tissue for 5 to 10 mm (FIG 8F).

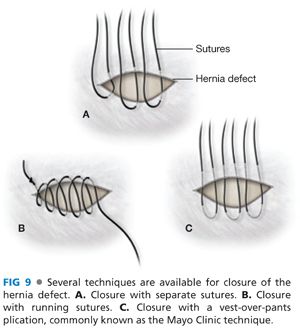

■ We close the umbilical and epigastric hernias in a horizontal line. Several options for suturing technique (separate sutures, running suture, or “vest-over-pants” plication sutures) (FIG 9A–C) and materials (monofilament vs. braided sutures; nonabsorbable, slowly absorbable, rapid absorbable) are available.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree