Flexible laryngoscopy has been used by physicians and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) for many years. Although there is some overlap in the areas of interest and the procedures used, the primary goals and objectives of physicians and SLPs are very different. Physicians employ the procedure to help them arrive at medical diagnoses that may subsequently lead to medical or surgical intervention. They attempt to uncover the underlying causes of anatomical abnormality (e.g., benign or malignant tissue changes, structural abnormalities in response to surgery or trauma, or congenital abnormality), abnormal movement (e.g., recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis), or neurosensory deficit (e.g., superior laryngeal nerve dysfunction) observed endoscopically. Depending on the diagnosis, physicians may suggest medical or surgical treatment options to eliminate the cause of the swallowing problem or they may refer the patient to an SLP for behavioral intervention.

SLPs do not use endoscopy to make medical or surgical diagnoses. Rather, they use endoscopy to observe, to explain, and to document the anatomical and physiologic correlates of the underlying medical problem. Such observations may then become the basis for making decisions about whether and what type of behavioral management may be indicated in the overall treatment plan for the patient. Many swallowing disorders requiring behavioral management may also necessitate medical/surgical diagnosis and treatment. Consequently, it is standard practice in speech-language pathology to require patients who have a suspected anatomical or physiologic disorder affecting swallowing to have a medical/surgical evaluation before behavioral management is considered. Because endoscopy is performed by both physicians and SLPs, either one combined examination or two examinations may be performed, after which the endoscopic findings can be evaluated as a team. SLPs may further employ videoendoscopy as a behavioral management tool.

This chapter briefly outlines how SLPs incorporate videoendoscopy into the evaluation and treatment of the patient with dysphagia. Complete consideration of the many theoretical, technical, and practical issues involved in dysphagia assessment and treatment is not possible here, and interested readers are encouraged to consult other works for additional detail regarding anatomy and physiology of normal and abnormal swallowing, clinical and instrumental assessment techniques, and behavioral and dietary management. For more information regarding the role of the SLP in the endoscopic assessment and management of patients with dysphagia, go to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) Website (www.asha.org) and review documents pertaining to endoscopy.

11.1 Indications for Endoscopy

SLPs evaluate and treat swallowing problems that primarily affect the oral and pharyngeal stages of swallowing. The first steps in the evaluation of dysphagia should include a review of the medical history, an interview with the patient, and a clinical examination of oral, laryngeal, and respiratory function. Following this, an instrumental examination is often performed.

Fluoroscopy, or the modified barium swallow (MBS), has been used as a standard examination for oropharyngeal dysphagia for many years, with endoscopy (fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing, FEES) emerging later as a diagnostic tool. The first published study describing the endoscopic swallowing procedure was in 1988. 1 Since that time, the merits of both examinations have been argued, but today they are both accepted as valid, sensitive, and useful examinations. 2, 3, 4

Many abnormal findings can be gleaned from either examination, but there are also unique applications that lead the discerning clinician to choose one procedure over the other. Indications for performing an endoscopic examination versus a fluoroscopic examination are listed in ▶ Table 11.1. First, there may be logistic or practical reasons for choosing endoscopy or fluoroscopy. For example, when the patient is critically ill, intubated, or requires continuous monitoring, videoendoscopy may be safer and easier for the patient to tolerate than videofluoroscopy. The portability of the endoscopic equipment allows it to be brought to the patient’s bedside, where the exam can be done in a safer and more comfortable environment than the fluoroscopy suite. On the other hand, a patient who is agitated and confused may do better with fluoroscopy, which is less invasive. There are also clinical indications for choosing one examination or the other. A common example is the patient who has a breathy or hoarse voice after intubation or surgery and for whom a direct look at the larynx would be beneficial. Structural and physiologic changes to the larynx that directly affect swallowing are best revealed by endoscopy. On the other hand, patients who complain of globus, or foreign-body sensation, may well have normal oral and pharyngeal swallowing, but abnormal esophageal motility or gastroesophageal reflux. Adding an esophagram to the MBS is an efficient way to detect this problem.

Indications for a FEES examination |

Need exam that day; cannot schedule fluoroscopy that day |

Positioning in fluoroscopy problematic: e.g., patient is bedridden, is weak, has contractures, is in pain, has decubitus ulcers, is quadriplegic, is wearing neck halo, is obese, or is on ventilator |

Transportation to fluoroscopy suite problematic: medically fragile/unstable patient (in ICU); cardiac or other monitoring in place; on ventilator; nursing/medical care must be with patient |

Transportation to hospital problematic: nursing home issues, including cost of transportation, resources needed to accompany patient, strain on patient, patient fearful of leaving familiar surroundings, etc. |

Concern about excess and repeated radiation exposure |

Concern about aspiration of barium, food, and/or liquid in patient with potentially profound dysphagia or very limited ability to tolerate any aspiration |

Postintubation or postsurgery where vagal nerve damage is possible |

Need to assess status of patient’s ability to manage secretions |

Want time to assess fatigue or swallow status over a meal |

Want therapeutic exam: time to try out several maneuvers, several consistencies, etc.; you want to try real foods; you want caregiver to hold a baby in several positions, etc. |

Need repeat exam to assess change; to assess effectiveness of maneuver |

Want to try biofeedback |

Indications for a fluoroscopy examination |

Patient will not accept/tolerate endoscopy |

Oral stage needs to be imaged |

Globus complaints: suspect esophageal stage problem or gastroesophageal reflux (GER); want to visualize esophageal motility and GER (must include esophagram for complete examination) |

Possible cricopharyngeal (CP) dysfunction |

Need to view cervical osteophytes |

Vague symptomatology from patient; need comprehensive view |

Need to better identify amount of aspiration of thin liquids during the swallow |

*FEES® is a copyrighted trademark of Susan E. Langmore, PhD. Use of the acronym FEES indicates that the endoscopic examination of pharyngeal swallowing herein performed or reported on was consistent with the procedure developed by Susan E. Langmore, PhD, and described in this chapter. |

Children with dysphagia also benefit from endoscopy. Some advantages for infants or children are the ability to be tested in a natural seating position (e.g., held in the parent’s arms), with typical liquids or foods, and the absence of radiation exposure. Voluntary compliance and cooperation from children are not always certain, however.

The views provided by videoendoscopy and videofluoroscopy are distinctly different. Fluoroscopy provides both coronal (frontal) and sagittal (lateral) planes, imaging the shadow of oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal structures. Endoscopy offers a transverse (axial) view, looking directly at the nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx from above. The endoscopic view is obliterated for about 0.5 seconds during the height of each swallow, except in cases where the swallow is so weak that the air space is not obliterated. The fluoroscopic view is limited by radiation exposure constraints, so the fluoroscopy unit is generally turned off between swallows, and total viewing time is limited to 3 to 5 minutes. Endoscopy can provide a constant view over a prolonged period of time, including the period between swallows when important events can take place. Fluoroscopy can provide a clearer representation of subglottic aspiration, whereas endoscopy reveals the location of the bolus within the hypopharynx and within the larynx with more specificity.

Although there are significant differences between the two procedures, they have similar purposes and outcomes. Both fluoroscopic and endoscopic procedures can be used to detect the presence of dysphagia, both can reveal the nature of the problem, and both will allow the examiner to make the recommendations needed for adequate management of the problem.

11.2 Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing Protocol

Langmore et al 1, 5 published the first description of the FEES procedure for evaluating swallowing with endoscopy. The FEES acronym was copyrighted to distinguish it from a laryngeal examination done by an otolaryngologist and to define it as a comprehensive evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Equipment needed for a FEES examination includes a standard flexible laryngoscope attached to a video camera, a light source, a video recorder, and a monitor.

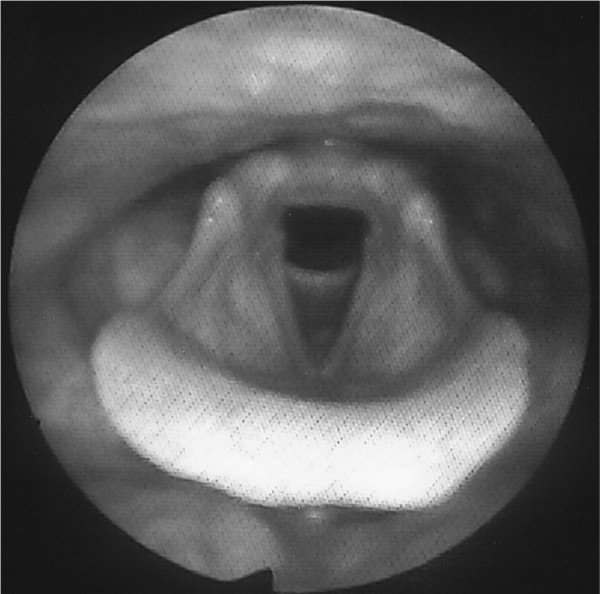

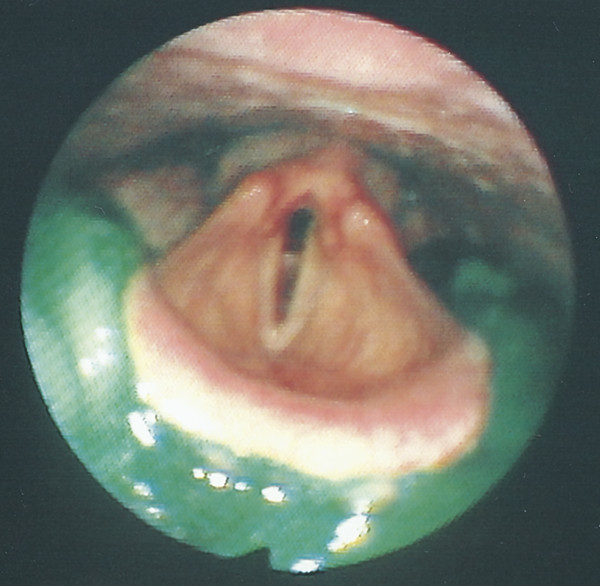

The laryngoscope is passed transnasally to a point just above the epiglottis where the hypopharynx and larynx can be optimally viewed ( ▶ Fig. 11.1). This is called the home position. For most of the exam, the home position is the position of choice; however, after each swallow, the scope is briefly passed into the laryngeal vestibule so that the true vocal folds and the subglottic shelf (membranous portion of the thyroid and cricoid cartilage positioned just below the true vocal folds) can be examined more closely for evidence of penetration or aspiration ( ▶ Fig. 11.2).

Fig. 11.1 View of the hypopharynx with the tip of the endoscope positioned just superior to the epiglottis so that the entire hypopharynx and larynx can be viewed. The typical position for the endoscope just prior to the swallow, it is called the home position.

Fig. 11.2 Close-up view of the larynx, including arytenoids, true vocal folds, and subglottic shelf. This view should be obtained between swallows for a brief period to inspect for signs of aspiration.

Patient comfort is paramount for this examination because the objective is to assess habitual swallowing function and to be able to keep the endoscope in place for as long as 20 to 30 minutes. Some patients request topical anesthesia to help dull sensation inside the nose. In this case, the examiner can administer a very small amount of topical anesthetic in the nares that will be used to pass the endoscope. The use of anesthesia during a FEES examination has been questioned because it might depress sensation in the pharynx or larynx and adversely affect swallowing function. In a series of 3 studies done recently, the authors studied the effect of different doses of lidocaine on swallow safety and patient comfort. 6, 7, 8 They concluded that 0.2ml of 4% atomized topical lidocaine for a FEES examination had no effect on penetration and aspiration scores or on residue scores in patients with dysphagia. However, it did improve patient-reported comfort levels and tolerance during the examination.

The FEES® protocol is shown in ▶ Table 11.2. There are three parts to a complete FEES examination. Part I is a direct examination of the base of the tongue and velopharyngeal (VP), pharyngeal, and laryngeal function. Anatomy and secretions within the hypopharynx (HP) are also noted. Part II requires the patient to eat and drink food and liquid while swallowing function is directly assessed. Part III includes the introduction of therapeutic maneuvers to try to remediate the problem.

Patient Name: | |

Date: | |

Examiner: | |

I. Anatomical–Physiologic Assessment | |

A. Velopharyngeal Closure | |

Task: | Say “ee,” “ss,” other oral sounds; alternate oral and nasal sounds (“duh-nuh”) |

Task: | Dry swallow |

Optional task: | Swallow liquids and look for nasal leakage |

B. Appearance of Hypopharynx (HP) and Larynx at Rest | |

Scan around entire HP to note symmetry and abnormalities that impact swallowing and might require referral to otolaryngology or other specialty. | |

Optional task: | Hold your breath and blow out cheeks forcefully (piriform sinuses) |

C. Handling of Secretions and Swallow Frequency | |

Observe amount and location of secretions and frequency of dry swallows over a period of at least 2 minutes | |

Task: | If no spontaneous swallowing noted, cue the patient to swallow |

Go to Ice Chip Protocol if consistent secretions in laryngeal vestibule or if no ability to swallow saliva. | |

D. Base of Tongue and Pharyngeal Muscles | |

1. Base of Tongue Task: Say “earl, ball, call” or other post-vocalic “l” word several times | |

2. Pharyngeal Wall Medialization | |

Task: | Screech; hold a high-pitched, strained “ee” |

(Task: see Laryngeal Elevation task below) | |

E. Laryngeal Function | |

1. Respiration | |

Observe larynx during rest breathing (respiratory rate; adduction/abduction) | |

Tasks: | Sniff, pant, or alternate “ee” with light inhalation (abduction) |

2. Phonation | |

Task: | Hold “ee” (glottic closure) |

Task: | Repeat “hee-hee-hee” 5 to 7 times (symmetry, precision) |

3. Laryngeal elevation | |

Glide upward in pitch as high as possible; hold it (pharyngeal walls usually also recruited) for a second or two (arytenoids should lift/move closer to camera). | |

4. Airway Protection | |

Task: Task: | Hold your breath lightly (true vocal folds) Hold your breath very tightly (ventricular folds; arytenoids) |

Task: | Hold your breath to the count of 7 |

Optional: | Cough, clear throat, Valsalva maneuver |

F. Sensory Testing | |

Note response to presence of scope | |

Optional task: | Lightly touch aryepiglottic (AE) folds |

Note: Additional information about sensation will be obtained in Part II and formal testing can be deferred until the end of the examination if desired. | |

II. Swallowing of Food and Liquid: All foods/liquids dyed green or blue with food coloring | |

Consistencies to try will vary depending on patient needs and problems observed; suggested consistencies to try: | |

Ice chips: | usually 1/3 to 1/2 teaspoon, dyed green |

Thin liquids: | milk, juice, formula. Milk or other light-colored thin liquid is recommended for visibility. Barium liquid is excellent to detect aspiration. You might need to retract the scope to prevent gunking during the swallow when using milk or barium. |

Thick liquids: | nectar or honey consistency; milkshakes |

Puree | |

Semisolid food: | mashed potato, banana, pasta (does not need teeth/mastication) |

Soft solid food: | bread and cheese, soft cookie, casserole, meat loaf, vegetables (requires some chewing with teeth) |

Hard, chewy, crunchy food: | meat, raw fruit, green salad |

Mixed consistencies: | soup with food bits, cereal with milk |

Amounts/Bolus Sizes | |

If measured bolus sizes are given, a rule of thumb that applies to many patients is to increase the bolus size with each presentation until penetration or aspiration is seen. When that occurs, repeat the same bolus size to determine if this pattern is consistent. If penetration/aspiration occurs again, do not continue with that bolus amount. The following progression of bolus volumes is suggested: | |

<5 cc if patient is medically fragile and/or pulmonary clearance is poor | |

5 cc (1 teaspoon) | |

10 cc | |

15 cc (1 tablespoon) | |

20 cc (heaping tablespoon, delivered) | |

Single swallow from cup or straw: monitored or self-presented | |

Free consecutive swallows: self-presented | |

The FEES Ice Chip Protocol | |

Part I: | Emphasize anatomy, secretions, laryngeal competence, sensation |

Note spontaneous swallows, cued swallow | |

Part II: | Deliver ice chips |

Note effect on swallowing, effect on secretions, cough if aspirated | |

Part I is an extension of the oral and motor clinical examination done to examine the lip, tongue, and jaw movement. This is a critical part of the examination because it helps the examiner understand the underlying anatomical or physiologic cause of the dysphagia. The endoscopic view provides a direct view of the mucosa overlying the structures of interest. The size, shape, and symmetry of the pharyngeal and laryngeal structures are observed for their effect on swallowing function. The depth of the lateral channels and resting position of the epiglottis are appreciated for their ability to contain a spilled or retained bolus. Edema and erythema are noted. Any suspicious growths or unusual appearance of the mucosal surface should alert the SLP to a possible medical pathology and warrant referral to otolaryngology.

The FEES protocol then directs the examiner to ask the patient to perform a variety of tasks that recruit velopharyngeal, base of tongue, pharyngeal, and laryngeal movement. Parameters of interest include strength, range, symmetry, and briskness of movement. Most of the tasks require the patient to speak, but some can be tested even in a confused or nonspeaking patient, such as breath hold or cough. Glottal closure or airway protection is tested in detail because this function is so critical for prevention of aspiration.

Over the first few minutes of the examination, the examiner observes the status of any standing secretions, the ability of the patient to swallow or clear these secretions, and the frequency of spontaneous dry swallows. The presence of pooled secretions in the larynx has been shown to be an excellent predictor of aspiration of food and liquid and a significant predictor of aspiration pneumonia, and is therefore an important part of the FEES examination. 9, 10, 11

At the conclusion of Part 1, laryngeal sensation can be directly assessed. In previous years, Pentax (Pentax Precision Instrument Corp, Orangeburg, NY) manufactured a piece of equipment that emitted a measured air pressure. The air pressure was fed through a catheter that either attached to a laryngoscope or was fed through a sheath covering the laryngoscope. The tip of the scope was positioned directly over the arytenoid cartilage and a puff of air was delivered to the mucosa overlying the arytenoid. At a certain pressure, as threshold was reached, a laryngeal adductor reflex (LAR) was triggered, manifest as a brief closure of the vocal folds. This equipment is no longer manufactured so the air pulse test is rarely done. In its place, most examiners test sensory response by administering the ‘touch’ test. This is done by lightly and briefly touching both arytenoids with the tip of the scope. At threshold or higher, the same LAR is elicited. At very high pressures, the patient may cough, phonate, or display some other behavior that suggests that they felt the touch. Obviously, the touch test is not easily calibrated and usually delivers a much stronger stimulus than the air pulse test. The response to a light touch is generally ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response rather than determining the exact air pressure that evokes the LAR. However, the advantage of the touch test is that it is readily available. A recent report compared the significance of these two methods of testing ‘sensory response’ .12 In their preliminary report, the authors tested 14 participants with both methods before giving them a FEES examination. They found that the air pulse method identified more sensory impairments, but the impairments were not associated with abnormal penetration-aspiration scores (p = 0.46). The touch method identified fewer sensory impairments but abnormal scores (no LAR) were significantly associated with abnormal penetration-aspiration scores (p = 0.05). The primary author is continuing to test more patients with dysphagia with the Touch test to determine its validity in a larger sample of patients. Sensory testing is usually done at the end of a FEES examination, just before removing the scope. Sometimes it is not needed because by that point in the exam, the patient’s response to sensory stimuli in the HP is known and direct testing is unnecessary.

When all the components of Part I have been tested, the FEES exam progresses to Part II, in which food and liquid are given and swallowing of these materials can be directly observed. A variety of foods and liquids in varying volumes and consistencies are given to patients, and their ability to swallow them safely and adequately is noted. Every bolus is dyed green or blue so that it is more visible and distinct from surrounding mucosal surfaces. The liquid bolus to be used poses some problems. Juice or green-tinged water makes an excellent bolus for observing spillage, but if they are aspirated, they may easily be missed. When the question is whether or not the patient aspirates, the liquid to use must reflect the light and, ideally, coat the mucosal surface. Use of milk, vanilla-flavored formula, or barium liquid is recommended for this purpose. However, these liquids often coat the tip of the endoscope as well and reduce the view. I generally use both kinds of liquids during the examination. I visualize spillage with the juice over several swallows and then, at the end of the examination, I retract the scope up to the nasopharynx as the patient swallows the barium liquid. After the swallow, I advance the scope quickly to the larynx and look for any signs of aspiration.

The FEES examination may be structured, with measured bolus sizes trialed, or the examination can be very unstructured, by simply asking the patient to eat everything on the plate in front of him and delivering no specific instructions. The examiner must make this clinical decision. Abnormal function is identified by signs like residue, spillage, laryngeal penetration, and aspiration of material below the true vocal folds. The anatomical or physiologic cause of the swallowing problem is determined by studying the pattern of swallowing and by relating the findings back to Part I of the study. This is discussed further in the next section.

As soon as a problem is identified, Part III commences. The examiner may want to intervene immediately with appropriate therapeutic alterations to observe their effect on swallowing. Interventions might include instructing the patient to assume another posture, such as chin-tuck, teaching the patient a swallow maneuver, such as the controlled breath hold prior to swallowing, or adjusting the bolus consistency, size, or method of delivery. Alternatively, the examiner may want to wait through several swallows before intervening in order to more accurately assess the real risk of aspiration. For example, it may be useful to see how the patient spontaneously responds to a buildup of residue before trying to reduce it. The examination ends when the examiner understands the nature of the problem, has determined which bolus amounts and consistencies can be swallowed effectively and safely, and has noted what therapeutic alterations facilitate swallowing.

Whenever possible, the patient, the family, and the nursing staff members who feed the patient are involved in the examination and participate in decision making regarding possible treatment for the swallowing problems that are observed. It has been our clinical experience that education of, and collaboration with, these significant persons are the most effective means of developing realistic and meaningful treatment goals and ensuring compliance with the treatment plan. Generally, we have the patient face the monitor during the entire examination so that patient education and biofeedback, using the image on the monitor, can be incorporated into the examination itself.

11.2.1 Scoring and Interpretation

Many of the major findings from a FEES exam can be identified during the examination by simply noting the abnormal findings as they occur. Examples of possible observations include spillage of pureed material to the level of the piriforms before the swallow, residue remaining in the right lateral channel, aspiration of liquid before the swallow, and so on. However, to interpret the examination and determine why the problems occurred, it is usually necessary to review the examination at least one time, often pausing to play back some portion in slow motion.

When scoring and reporting on a FEES exam, it is sometimes useful to describe the abnormal findings that occur over time with each consistency, for example, to describe how the patient handled pureed food, then solid food, and finally liquids. Other times, it is more useful to discuss the problems in relation to the timing of the swallow, that is, to discuss the oral preparatory phase, the transitional time or the initiation of the swallow, the effectiveness of bolus clearance, and the patient’s response to residue after the swallow. This, again, is an individual decision.

Interpretation requires the examiner to relate the individual findings to the underlying anatomy and pathophysiology that created the particular pattern observed. This not only explains the dysphagia, but also provides the rationale for the treatment plan. There are four major types of problems that occur in the oral and pharyngeal stages of swallowing that can be identified from the examination: (1) inability to prepare the food orally, (2) inability to initiate the swallow in a timely and coordinated manner, (3) inadequate airway protection or VP closure during the swallow, and (4) incomplete bolus clearance. These problems can all be revealed by a FEES examination, although the first problem, oral preparation, is also dependent on clinical observations of the patient.

Inability to prepare the food orally. The clinical interview, oral motor examination, and observations during eating will explain why food is not prepared well. Mastication, forming a bolus, and containment of the food in the mouth require a mobile tongue, some teeth that are aligned, lips that can close, a jaw that can move, buccal tension, and a degree of alertness and self-monitoring. If the oral preparatory stage is impaired, the pharyngeal consequences can be directly viewed endoscopically. The masticated bolus may leak over the base of tongue during mastication and liquid may not be contained in the mouth. Food may stick in the valleculae, while liquid may flow around the epiglottis to the piriforms.

Inability to initiate the swallow in a timely and coordinated manner. A major cause for dysphagia is mistiming of lingual bolus propulsion and the pharyngeal response at the initiation of the swallow. This problem may take many forms, is one of the most common abnormalities reported for patients with neurogenic dysphagia, and is a frequent cause of aspiration. 13, 14 The problem is visualized during the examination as material spilling into the hypopharynx prior to the initiation of the swallow ( ▶ Fig. 11.3). If the spillage is excessive, the bolus will overflow the lateral channels or the piriforms and enter the laryngeal vestibule. Because the swallow has not yet begun, the airway will likely be open, and thus the bolus can enter the glottis and be aspirated. All these events are directly viewed with endoscopy because the airspace has not yet closed. Spillage can be attributed to poor oral control, lingual weakness, altered tongue anatomy, reduced lingual sensation, difficulty initiating the swallow, or lack of cortical monitoring. In all cases, the bolus falls into the pharynx too early, before the swallow is triggered. Pharyngeal delay time is a temporal measure of how long the bolus is in the pharynx before the swallow begins. This is a well-known measure of the problem and can be readily calculated from endoscopy as well as fluoroscopy. 15, 16 Recent research has established that some spillage is normal, especially with solid food, and the cut-off for normal vs. pharyngeal delay has become clouded. 17, 18 Rather than focusing solely on a temporal measure of delay, the examiner should appreciate all the factors that cause one person to aspirate more easily than another. The length of time the bolus is in the pharynx, combined with the bolus size, along with the significant influence of anatomy on directing the path of the bolus, will cumulatively determine whether a person will run into trouble at the initiation of the swallow. For example, some persons have an epiglottis with a flattened-down tip that rests directly on the base of the tongue. Even a small amount of spillage cannot be tolerated by these individuals, because the bolus will be directed into the vestibule rather than into an open vallecular recess.

Inadequate airway protection during the swallow. Inadequate airway protection results in aspiration of material during the swallow. The underlying pathophysiology of aspiration is often thought to be weakness or incomplete movement of the laryngeal structures that participate in the swallow (i.e., epiglottic retroversion, arytenoid adduction and forward tilt, true and false vocal fold adduction). More often, however, aspiration occurs because of delayed airway closure and reflects a delayed or mistimed initiation of the swallow. If there is no spillage whatsoever prior to the onset of the swallow, and the bolus is still aspirated during the swallow, one can assume airway protection is compromised.

Fig. 11.3 Spillage of pureed material before the swallow has begun. The material has spilled nearly to the piriform recesses without any indication of the swallow initiation, indicating a pharyngeal delay.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree