Chapter Thirty-Seven. The first stage of labour

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction 497

Maternal position in the first stage of labour 506

Immersion in water 507

Monitoring the maternal condition 508

Physiology of the first stage of labour

Uterine activity in labour

In early labour, contractions may be 15–20 min apart and are fairly weak, lasting for about 30 s. These may not be recognised as labour pains by the woman for a while. In established labour, the uterus contracts 3–4 times every 10 min, and in advanced labour each contraction may last 50–60 s and is powerful. Contractions can be measured in mmHg (millimetres of mercury) by the pressure they exert on the amniotic fluid. This is called the intrauterine hydrostatic pressure. The resting pressure exerted by the muscular myometrium is about 5 mmHg. In pregnancy, the intensity of uterine contractions may reach 30 mmHg and up to 60–80 mmHg in labour.

Several concepts are described in relation to uterine activity in labour. The spread of each contraction across the uterine muscle is thought to begin in the fundus near the cornua, spreading outwards and downwards, remaining most intense in the fundus and being weakest in the lower uterine segment, a phenomenon known as fundal dominance. The spread of myometrial electrical activity to its maximum takes about 1 min and the same time is taken for the wave of contraction to pass off. This allows progressive dilatation of the cervix and, as the upper segment thickens and shortens, the fetus is propelled down the birth canal. During contractions, the upper and lower poles of the uterus act in harmony, with contraction and retraction of the upper pole, and dilatation of the lower pole to allow expulsion of the fetus. This is known as polarity.

Uterine muscle in labour has the unique property of contraction and retraction (Fig. 37.1). Following each contraction, the muscle fibres do not completely relax but retain some of the shortening of contraction. This is called retraction and leads to the progressive shortening and thickening of the upper uterine segment (UUS) and the diminishing of the uterine cavity to accommodate the descending fetus. A physiological ridge forms between the UUS and the lower uterine segment (LUS), known as a retraction ring (see Ch. 44 for the abnormal Bandl’s ring which is an exaggerated pathological retraction ring that develops in obstructed labour and becomes visible above the symphysis pubis).

|

| Figure 37.1 Retraction of the uterine muscle fibres. (1) Relaxed. (2) Contracted. (3) Relaxed but retracted. (4) Contracted but shorter and thicker than those in (2). (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

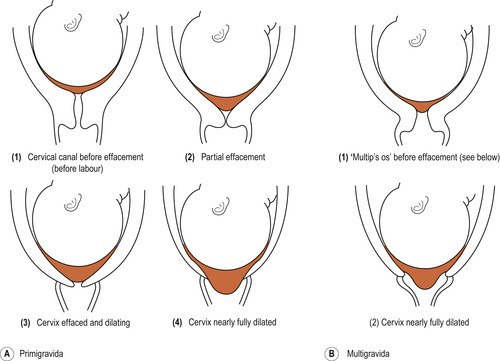

Effacement or ‘taking up’ of the cervix is the term used to describe the gradual mergence of the cervix into the LUS. In primigravidae, this process is sometimes complete before the onset of labour and before dilatation of the external cervical os occurs (Fig. 37.2A). In multigravidae, a perceptible cervical canal remains until labour is well established, a finding midwives refer to as a ‘multip’s os’. During labour there is dilatation of the external os until it is large enough for the widest diameter of the presenting part to pass through (Fig. 37.2B). In a fetus at term presenting by the vertex, the diameter of the cervix would normally have to reach 10 cm but this would be less in a fetus with a smaller head. As the cervix begins to dilate, the operculum or mucous plug formed in pregnancy is lost around the time of the commencement of labour and the woman will notice a mucoid discharge, which may be blood-stained. This is termed the show. The blood originates from ruptured capillaries when the lining of the cervix is stretched or where the chorion has become detached from the dilating cervix.

|

| Figure 37.2 (A) Effacement and dilatation of the cervix in a primigravida. (B) Effacement and dilatation of the cervix in a multigravida. |

Mechanical factors

Besides uterine action, there are mechanical forces that aid dilatation of the cervix. As the lower uterine segment is stretched, the chorion is detached from it. In normal labour the increased intrauterine pressure during contractions forces a well-flexed head snugly against the cervix, trapping a small amount of amniotic fluid in front of the head separate from the rest of the fluid surrounding the body of the fetus. This small sac of fluid is known as the forewaters and the rest of the fluid as the hindwaters. The forewaters bulge through the cervix, becoming more tense during contractions (Fig. 37.2A-4/B-2). This separation of the forewaters from the larger volume of the hindwaters keeps the membranes intact during the first stage of labour, providing a barrier against ascending infection.

When the membranes remain intact, the pressure of each contraction is exerted on the fluid and, as fluid is not compressible, pressure is equalised throughout the uterus. This is known as general fluid pressure (Fig. 37.3). If the membranes are ruptured and amniotic fluid is reduced, contraction pressure is applied directly to the fetus. The placenta is compressed between the uterine wall and the fetus, which further reduces the oxygen supply to the fetus. Therefore, there are two good reasons for maintaining intact membranes: to reduce the risk of infection and to maintain a good oxygen supply to the fetus. In a systematic review of 14 studies (4893 women) exploring amniotomy in labour, Smyth et al (2007) did not find any evidence of a statistical difference in length of first stage of labour, maternal satisfaction with childbirth experience or low Apgar score of < 7 at 5 min. However, amniotomy was associated with an increased risk of delivery by caesarean section compared to women in the control group. The physiological moment for the membranes to rupture is when the cervix is fully dilated and no longer able to support the forewaters and the force of the uterine contractions reaches maximum. The evidence remains clear that routine amniotomy during the first stage of labour can never be justified as standard care in normal low-risk women (NICE 2007, Smyth et al 2007).

|

| Figure 37.3 General fluid pressure. (From Fraser & Cooper 2009, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

During each contraction, the force of the fundal contraction is transmitted to the upper pole of the fetus, down the long axis of the fetal spine, causing increasing flexion of the head. This ensures that the smallest possible circumference, which is the circular vertex, is applied to the circular cervical os. This is known as fetal axis pressure (Fig. 37.4).

|

| Figure 37.4 Fetal axis pressure. (From Fraser and & Cooper 2009, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Phases of the first stage of labour

The present understanding of labour is based on the work of Emanuel A Friedman. He developed the graphic representation of labour by plotting cervical dilatation and descent of the presenting part against time. In normal labour, the rate of dilatation of the cervix follows a sigmoid-shaped curve. There are three distinct parts:

1. An initial part where there is little progress in cervical dilatation, which Friedman called the latent phase.

2. A part of the curve where there is rapid progress in dilatation, called the active phase.

3. A part of the curve where dilatation slows, called the deceleration phase (also termed the transitional phase).

The latent phase, which lasts until cervical dilatation is about 3–4 cm, can take 6–8 h in a primigravida. The active phase occurs with rapid dilatation of the cervix at about 1 cm/h in a primigravida and 1.5 cm/h in a multigravida. The length of established first stage of labour varies between women. First labours last on average 8 h and are unlikely to last over 18 h. Second and subsequent labours last on average 5 h and are unlikely to last over 12 h (NICE 2007). Plotting the rate of cervical dilatation has been commonly carried out in labour (a cervicograph), an average duration is indicated in Figure 37.5.

|

| Figure 37.5 A cervicograph. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Individualised care

Childbearing experience for women encompasses both a biological and a social event. The midwife should carefully consider these aspects when planning care with the labouring woman. This should include the following:

• Assess the woman’s needs and expectations, using a clear risk-assessment strategy.

• Plan care accordingly to meet the specific needs and expectations.

• Carry out the plan.

• Evaluate the effect of the care and modify it if necessary.

The physiological aspects of care in labour include assessing progress, positioning of the woman, nutrition and hydration and monitoring the condition of woman and fetus.

Assessing progress in the first stage of labour

When as much detail as possible has been ascertained about the progress of labour prior to admission, the woman is examined to confirm details given verbally and to establish a baseline on which to judge further progress. An abdominal examination is made and this may be followed by a vaginal examination. Progress can be considered as a function of descent of the presenting part through the pelvis and dilatation of the cervix. The presence of one in the absence of the other may suggest lack of progress and is a cause for concern.

Abdominal examination in labour

Most of the aims of abdominal examination, considered by Viccars (2003) in the context of antenatal care, apply equally well to labour. These are to assess fetal size and well-being, to diagnose the location of fetal parts—in particular, lie, presentation, position and engagement—and to detect any deviation from normal. Abdominal examination should always be carried out prior to performing a vaginal examination (if required) and repeated abdominal examinations can be used to assess descent of the presenting part.

Inspection

The size and shape of the uterus can be of value in ensuring that there is a normal longitudinal lie. The uterus will appear ovoid in shape. In the rare instance of a transverse lie, the uterus may appear to be low and broad. If there is a saucer-shaped depression below the umbilicus, the fetus may be lying in an occipitoposterior position. Fetal movements may be seen and can help in the diagnosis of position.

Palpation

The following terms are used to describe fetal palpation:

• Presentation: That part of the fetus which lies at the pelvic brim or in the lower pole of the uterus. This is usually cephalic but other possible presentations include breech, face, brow and shoulder.

• Attitude: The relationship of the fetal head and limbs to its body. It may be fully flexed, deflexed or partially or completely extended.

• Denominator: Identifies the name of the part of the presentation used when referring to fetal position in relation to the pelvis. Each presentation has a different denominator: occiput for cephalic presentation; sacrum for breech presentation; and mentum for face presentation.

• Position: The relationship of the denominator to six key points on the maternal pelvic brim. These points are right and left anterior, right and left lateral, and right and left posterior. However, a further two points could be direct anterior and direct posterior.

• Engagement of the fetal head: This occurs when the widest presenting transverse diameter has passed through the brim of the pelvis, i.e. biparietal diameter of 9.5 cm in cephalic presentation.

Practitioners often get the terms ‘presentation’ and ‘presenting part’ confused. The presenting part refers to that part of the fetus that lies over the cervical os during labour and on which the caput succudaneum may form (e.g. in a cephalic presentation); the presenting part would be the posterior part of the anterior parietal bone (Downe 2003).

Fundal palpation (Fig. 37.6A) (taking into account the overall size of the uterus) allows a judgement of the gestational age to be made (Fig. 37.7). It is also a necessary part of determining the lie of the fetus (Fig. 37.8).

|

| Figure 37.6 Types of palpation per abdomen. (A) Fundal, (B) Lateral, (C) Pelvic. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 37.7 The height of the fundus at different stages of pregnancy. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 37.8 The lie of the fetus. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Lateral palpation (Fig. 37.6B) is used to locate the fetal back to determine position. The length and frequency of contractions should be noted by palpation rather than by the reaction of the woman. The hardness of the abdomen may give a good indication of the strength of the contractions.

Pelvic palpation (Fig. 37.6C) using both hands identifies the presenting part (Fig. 37.9) and the amount of flexion (Fig. 37.10), and engagement of the head can be assessed by estimating the amount of head still present above the pelvic brim. If the head is engaged, it will be possible to feel less than half the fetal head above the pelvic brim and the head will not be mobile. It may not be possible to palpate the occiput if the head is deeply engaged (Fig. 37.11). Engagement is a good sign and indicates that the bony pelvis is adequate for the passage of the fetus and a vaginal delivery should follow. Stuart (2003) summarises descent of the head by abdominal assessment, which can be described in fifths of the head felt above the pelvic brim. Determination of the level of the fetal head by abdominal palpation excludes the variability due to caput and moulding and that produced by a different depth of pelvis.

|

| Figure 37.9 The presentation of the fetus. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 37.10 The attitude of the fetus. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 37.11 Examination per abdomen to determine the descent of the fetal head in fifths. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Auscultation

Listening to the fetal heart is an important part of any abdominal examination as it enables the practitioner to make an assessment of fetal well-being. The point of maximum intensity is located by considering the position of the fetus (Fig. 37.12). As labour progresses and descent takes place, the point of maximum intensity will change. Therefore the position of the Pinard’s stethoscope on the abdomen will also change to ensure the best possible clarity of the fetal heartbeat in assessing, rate, rhythm and frequency. Continuous monitoring of the fetal heart may be necessary where there is doubt about fetal well-being.

|

| Figure 37.12 The approximate points of the fetal heart sounds in vertex and breech presentations. ROA, right occipitoanterior; ROP, right occipitoposterior; LOA, left occipitoanterior; LOP, left occipitoposterior; RSA, right sacroanterior; RSP, right sacroposterior; LSA, left sacroanterior; LSP, left sacroposterior. |

Vaginal examination in labour

Vaginal examination has been routine practice for generations to assess progress in labour. The rationale for why vaginal examination is required in a low-risk situation is still unclear, with evidence to support it being unnecessary and a traumatic experience for women (NICE 2007). With good physiological knowledge of labour, healthcare professionals can use their skills in deciphering progress rather than using intervention. The purple line which creeps up the ‘natal cleft’ (cleavage between the buttocks) can be used as a measure of cervical dilatation (Byrne & Edmonds 1990). Hobbs (2003) proposes that this non-intervention method would be a useful tool to adopt in low-risk situations. At the start of labour the ‘purple-red line’ begins at the anal margin and gradually creeps up the anal cleft (much like mercury in a thermometer) as cervical dilatation occurs. Vaginal examinations in low-risk women are only necessary if they add further information to the decision-making process of the women’s care as these examinations can ultimately cause more distress and discomfort (NICE 2007). Health professionals should use their clinical judgement along with a fully informed decision from the woman prior to conducting a vaginal examination. Low-risk women with a strong history of pre-labour spontaneous rupture of membranes should not be offered a speculum examination routinely, but if there is any uncertainty then a speculum examination should be offered. However, if no uterine contractions are present then a digital vaginal examination should be avoided (NICE 2007).

It is acknowledged that vaginal examinations are not always required in labour. The following rationale for conducting a vaginal examination in labour are suggested:

• To make a positive identification of presentation.

• To determine whether the head is engaged if there is doubt.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree