CHAPTER 64 Peritoneum and peritoneal cavity

The peritoneum is the largest serous membrane in the body, and its arrangements are complex. In males it forms a closed sac, but in females it is open at the lateral ends of the uterine tubes. It consists of a single layer of flat mesothelial cells lying on a layer of loose connective tissue. The mesothelium usually forms a continuous surface, but in some areas may be fenestrated. Neighbouring cells are joined by junctional complexes, but probably permit the passage of macrophages. The submesothelial connective tissue may also contain macrophages, lymphocytes and adipocytes (in some regions). Mesothelial cells may transform into fibroblasts, which may play an important role in the formation of peritoneal adhesions after surgery or inflammation of the peritoneum.

GENERAL ARRANGEMENT OF THE PERITONEUM

In utero, the alimentary tract develops as a single tube suspended in the coelomic cavity by ventral and dorsal mesenteries (see Ch. 73). Ultimately, the ventral mesentery is largely resorbed, although some parts persist in the upper abdomen and form structures such as the falciform ligament. The mesenteries of the intestines in the adult are the remnants of the dorsal mesentery. The migration and subsequent fixation of parts of the gastrointestinal tract produce the so-called ‘retroperitoneal’ segments of bowel (duodenum, ascending colon, descending colon, and rectum), and four separate intraperitoneal bowel loops suspended by mesenteries of variable lengths. These are all covered by visceral peritoneum which is continuous with the parietal peritoneum covering the posterior abdominal wall. The first intraperitoneal loop is formed by the intraperitoneal oesophagus, the stomach and first part of the duodenum. The second loop is made up of the duodenojejunal junction, jejunum, ileum and occasionally the caecum and proximal ascending colon. The third loop contains the transverse colon and the final loop contains the sigmoid colon and occasionally the distal descending colon.

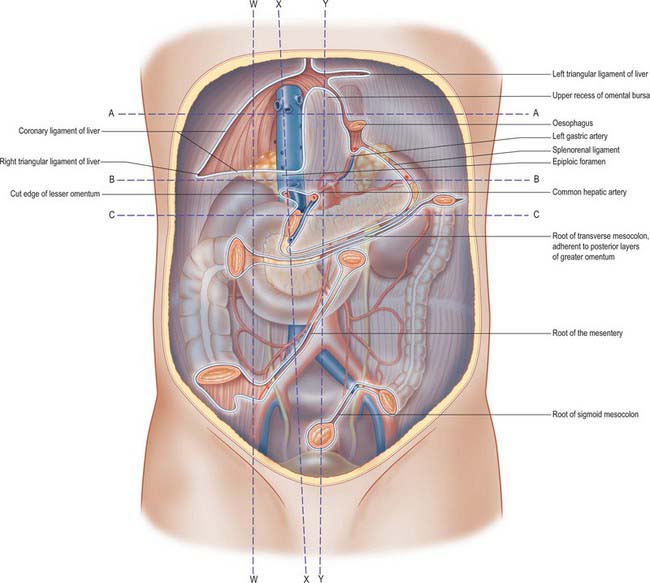

Where the visceral peritoneum encloses or suspends organs within the peritoneal cavity, the peritoneum and related connective tissues are known as the peritoneal ligaments, omenta or mesenteries. All but the greater omentum are composed of two layers of visceral peritoneum separated by variable amounts of connective tissue. The greater omentum is folded back on itself and is therefore made up of four layers of closely applied visceral peritoneum, which are separated by variable amounts of adipose tissue. The mesenteries attach their respective viscera to the posterior abdominal wall: the attachment is referred to as the mesenteric root, and the peritoneum of the mesentery is continuous with that of the posterior abdominal wall in this area (Fig. 64.1).

Fig. 64.1 The posterior abdominal wall, showing the lines of peritoneal reflection, after removal of the liver, spleen, stomach, jejunum, ileum, caecum, transverse colon and sigmoid colon. The various sessile (retroperitoneal) organs are seen shining through the posterior parietal peritoneum. Note: the ascending and descending colon, duodenum, kidneys, suprarenals, pancreas and inferior vena cava. Line W–W represents the plane of Fig. 64.2. Line X–X represents the plane of Fig. 64.3. Line Y–Y represents the plane of Fig. 64.4. Line A–A represents the plane of Fig. 64.5A. Line B–B represents the plane of Fig. 64.5B. Line C–C represents the plane of Fig. 64.5C.

PERITONEUM OF THE UPPER ABDOMEN

The abdominal oesophagus, stomach, liver and spleen all lie within a double fold of visceral peritoneum which runs from the posterior to the anterior abdominal wall. This fold has no recognized name, but has been referred to as the mesogastrium by Coakley & Hricak 1999 because it is derived from the fetal mesogastrium. It has a complex attachment to the wall of the abdominal cavity and gives rise to the falciform ligament, coronary ligaments, lesser omentum (gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligaments), greater omentum (including gastrocolic ligament), gastrosplenic ligament, splenorenal ligament, and phrenicocolic ligament (Figs 64.2, 64.3, 64.4).

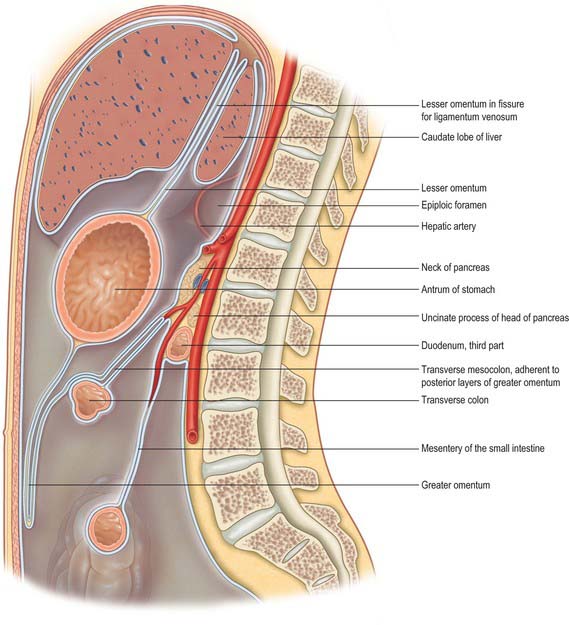

Fig. 64.2 Sagittal section through the abdomen to the right of the epiploic foramen along one line of W–W in Fig. 64.1.

Fig. 64.3 Section through the upper part of the abdominal cavity, along the line X–X in Fig. 64.1. The boundaries of the epiploic foramen are shown and a small recess of the lesser sac is displayed in front of the head of the pancreas. Note that the transverse colon and its mesocolon are adherent to the posterior two layers of the greater omentum.

Fig. 64.4 Sagittal section through the abdomen, approximately in the median plane. Compare with Fig. 64.1. The section cuts the posterior abdominal wall along the line Y–Y in Fig. 64.1. The peritoneum is shown in blue except along its cut edges, which are left white.

The falciform ligament

The falciform ligament is a thin anteroposterior peritoneal fold which connects the liver to the posterior aspect of the anterior abdominal wall just to the right of the midline. It extends inferiorly to the level of the umbilicus, and is widest between the liver and umbilicus. The ligament narrows superiorly as the distance between the liver and anterior abdominal wall reduces and narrows to just a centimetre or so in height over the superior surface of the liver. Its two peritoneal layers divide to enclose the liver and are continuous with the visceral peritoneum that is adherent to the surface of the liver. Superiorly, they are reflected onto the inferior surface of the diaphragm and are continuous with the parietal peritoneum over the right dome. At the posterior limit, or apex, of the falciform ligament, the two layers are also reflected vertically left and right, and are continuous with the anterior layers of the left triangular ligament and the superior layer of the coronary ligament of the liver. The inferior aspect of the falciform ligament forms a free border where the two peritoneal layers become continuous with each other as they fold over to enclose the ligamentum teres. Because the peritoneum of the falciform ligament is continuous with that covering the posterior abdominal wall and the periumbilical anterior abdominal wall, blood arising from retroperitoneal haemorrhage (commonly acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis) may track between the folds of peritoneum and appear as haemorrhagic discolouration around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign). Inflammatory change from the pancreas may spread via the gastrohepatic ligament (lesser omentum) and then via the falciform ligament to the umbilicus.

The peritoneal connections of the liver

The liver is almost completely covered in visceral peritoneum, and only the ‘bare area’ is in direct contact with the right dome of the diaphragm. Peritoneal folds, the ligaments of the liver, run from the liver to the surrounding viscera and to the abdominal wall and diaphragm (Fig. 64.5); they are described in detail in Chapter 68.

Fig. 64.5 Transverse sections through the abdomen. A, At the level of the line A–A in Fig. 64.1. The line passes through the bare area of the liver at the superior end of the lesser omentum. The parts of the left subphrenic space are clearly seen although they are continuous with each other. B, At the level of line B–B in Fig. 64.1, viewed from below. The peritoneal cavity is shown by a blue ‘wash’; the peritoneum and its cut edges in pale blue. C, Transverse section through the abdomen at the level of the line C–C in Fig. 64.1, viewed from below. Colours as in Fig. 64.1.

The right triangular ligament is a short V-shaped fold formed by the approximation of the two layers of the coronary ligament at its right lateral end, and is continuous with the peritoneum of the right posterolateral abdominal wall. The coronary ligament is reflected inferiorly and is directly continuous with the peritoneum over the upper pole of the right kidney. This fold is sometimes referred to as the hepatorenal ligament. The recess formed between the peritoneum of the inferior surface of the liver, the hepatorenal ligament and the peritoneum over the right kidney is known as the hepatorenal pouch (of Morison). In the supine position this is the most dependent part of the peritoneal cavity in the upper abdomen, and is a common site of pathological fluid accumulation.

The peritoneum is reflected inferolaterally from the posterior layer of the left triangular ligament onto the posterior abdominal wall above the oesophageal opening of the diaphragm. It lines the inferior surface of the left dome of the diaphragm and continues backwards onto the posterior abdominal wall. Inferiorly, it is reflected behind the spleen onto the most lateral part of the mesentery of the transverse colon and the splenic flexure. It continues down lateral to the descending colon into the pelvis, and forms the left paracolic ‘gutter’. Medially, the peritoneum covering the left upper posterior abdominal wall is reflected anteriorly to form the left layer of the upper end of the lesser omentum, the peritoneum over the left aspect of the abdominal oesophagus and the left layer of the splenorenal ligament.

The greater omentum

The greater omentum is the largest peritoneal fold and hangs inferiorly from the greater curvature of the stomach. It is a double sheet: each sheet consists of two layers of peritoneum separated by a scant amount of connective tissue. The two sheets are folded back on themselves and are firmly adherent to each other. The anterior sheet descends from the greater curvature of the stomach and first part of the duodenum. The most anterior layer is continuous with the visceral peritoneum over the anterior surface of the stomach and duodenum and the posterior layer is continuous with the peritoneum over the posterior wall of the stomach and pylorus. The anterior sheet descends a variable distance into the peritoneal cavity and then turns sharply on itself to ascend as the posterior sheet. The posterior sheet passes anterior to the transverse colon and transverse mesocolon. It is attached to the posterior abdominal wall above the origin of the small intestinal mesentery and anterior to the head and body of the pancreas. The anterior layer of the posterior sheet is continuous with the peritoneum of the posterior wall of the lesser sac. The posterior layer is reflected sharply inferiorly and is continuous with the anterior layer of the transverse mesocolon. The posterior sheet is adherent to the transverse mesocolon at its root and is often known as the gastrocolic ligament, which is the supracolic part of the greater omentum. In early fetal life the greater omentum and transverse mesocolon are separate structures, and this arrangement sometimes persists. During surgical mobilization of the transverse colon, the plane between the transverse mesocolon and greater omentum can be entered opposite the taenia omentalis, and the greater omentum can be separated entirely from the transverse colon and mesocolon if required. Access into the lesser sac can be obtained via this approach if the upper part of the posterior sheet of the greater omentum is then divided. This gives a relatively bloodless plane of entry for surgical access to the posterior wall of the stomach and to the anterior surface of the pancreas. The greater omentum is continuous with the gastrosplenic ligament on the left, and on the right it extends to the start of the duodenum. A fold of peritoneum, the hepatocolic ligament, may run from either the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver or the first part of the duodenum to the right side of the greater omentum or hepatic flexure of the colon.