Leigh Ann Difusco

Pediatric Surgery

Pediatrics is a specialty focused on the health and well-being of neonates, infants, children, and adolescents. The pediatric patient often needs surgery for congenital anomalies that threaten life or the child’s ability to function. Trauma also affects a child’s health far more often than an adult’s; injury is a common reason for surgical intervention. Pediatric surgery is an area of practice unto its own because the pediatric patient is so different from an adult. The field is even further subdivided into all the surgical specialties. It is important to recognize that the difference between pediatric care and adult care is not just a size issue; from birth onward, the body and organs exist in a continual state of development, and multiple physiologic changes occur with age. Major areas of distinction are the airway and pulmonary status, cardiovascular status, temperature regulation, metabolism, fluid management, and psychologic development. A thorough knowledge of these differences is integral to the provision of nursing care for the pediatric patient in the operating room (OR).

Advances in surgical interventions for children have been phenomenal for many reasons. The advancement of improved diagnostic and interventional technology, the development of new anesthetics and pharmacologic agents for pain management, and the creation of even smaller and more delicate instrumentation have revolutionized perioperative care of the pediatric population. Numerous pediatric surgeries that were once performed as open cavity procedures are now being done endoscopically with minimally invasive techniques, resulting in shorter hospital stays and faster recovery times. Improvements in the transport of critically ill children and the intensive care management of neonatal and pediatric patients as well as the development of new surgical procedures are also saving more lives yet presenting medical professionals with a new and unique set of problems as complex, medically fragile children are now surviving into adulthood.

Pediatric Surgical Anatomy

Airway and Pulmonary Status

Respiratory mechanics alter dramatically from infancy to adulthood, resulting from increases in airway size, transformations in the rigidity of airway and chest structures, and major changes in neuromuscular status. A proportionally large head, a short neck, and a large tongue in relation to jaw size create more of a challenge for airway management. The glottis is very anterior, moving from the level of the second cervical vertebra to the level of the third or fourth vertebra in the adult. The epiglottis is floppy and more curved, and the vocal cords are slanted anteriorly. The airway forms an inverse cone with the narrowest portion at the cricoid cartilage until 8 years of age; endotracheal tube size is therefore very important because a tube that passes easily through the glottis may be too tight at the subglottic area, compromising the child’s airway in the immediate postoperative period because of swelling. The infant is an obligate nasal breather, and the chest wall of an infant is very compliant, leading to increased work of breathing with any type of airway compromise. Infants also have type 2 respiratory muscle fibers until age 2 years, which fatigue more easily than type 1 muscle fibers. Premature infants are at risk for postanesthetic apnea until 60 weeks after conception age. There is a depression in the CO2 response curve in infants; compared with an adult, the respiratory rate does not increase as readily in response to a rising CO2 level, although all ages undergo a CO2 response depression related to inhalational agents and narcotics. One of the most important considerations is that children have a much smaller pulmonary functional residual capacity; a child becomes hypoxic more quickly if the airway is lost. Alveolar maturation is not complete until 8 years of age. Smaller airways have higher resistance; airway resistance decreases approximately 15 times from infancy to adulthood, again with a major change occurring around 8 years of age. It is important to note that smaller airways can become compromised with even a minor amount of swelling. An additional consideration in the pediatric setting is loose teeth. Loose teeth are common in children ages 5 to 14 years; a dislodged tooth is a potential airway foreign-body risk.

Cardiovascular Status

The most dramatic changes in the cardiovascular system occur at birth with the transition from fetal circulation. Even in full-term infants, persistent transitional circulation may occur. Heart rate is the predominant determinant of cardiac output in infants and children; bradycardia drastically decreases cardiac output and requires swift intervention. There is a decreased cardiac compliance because of a lower proportion of muscle to connective tissue until age 1 to 2 years, making infants preload insensitive. Young children are predisposed to parasympathetic hypertonia (increased vagal tone), which can be induced by painful stimuli such as laryngoscopy, intubation, eye surgery, or abdominal retraction. Attention to blood loss in young patients is very important because the patient’s total blood volume is very small. Blood volume in neonates is 80 to 90 mL/kg; at 1 to 6 years it is 70 to 75 mL/kg; and at age 6 years to adult it is 65 to 70 mL/kg. At birth, 70% to 90% of the hemoglobin is fetal hemoglobin with a high affinity for oxygen. It is normal for hemoglobin levels to fall at about 2 to 3 months of age (physiologic anemia) to a hematocrit level of 29% and a hemoglobin level of 10 mg/dL as the infant’s body begins to produce its own blood cells. A cardiology evaluation is essential if a murmur is auscultated. A murmur can be from a patent foramen ovale, which normally closes at 3 to 12 months; a patent ductus arteriosus, which can be present for up to 2 months; a previously undetected cardiac anomaly; or an innocent flow murmur. The evaluation is critical because anesthetic agents cause vasodilation and potentiate cardiac dysrhythmias.

Temperature Regulation

Infants and young children are most at risk of hypothermia because of their increased body surface area-to-weight ratio and thin fat layer. Cold stress leads to increased oxygen consumption, resulting in hypoxia, respiratory depression, acidosis, hypoglycemia, and pulmonary vasoconstriction. Hypothermia alters drug metabolism, prolongs the action of neuromuscular blockers, and delays emergence from anesthesia. The child’s temperature must be monitored continuously throughout the intraoperative experience. An axillary temperature probe is acceptable for short procedures in healthy children; an esophageal or rectal temperature probe provides more accurate monitoring of the child’s temperature for longer cases. Hyperthermia should also be avoided because it leads to increased oxygen consumption and increased fluid losses.

It is vital to maintain normothermia in children, and the easiest way to do this is by exposing only the area on which surgery is being performed. Additional thermoregulatory interventions include altering the room temperature before the child enters the room, using a water-filled temperature-regulating blanket under the patient, or using a forced-air warming blanket over nonsurgical areas of the child. An overhead heater can be used during the anesthetic induction and patient preparation period immediately before prepping and draping. The anesthesia ventilation circuit can be heated and humidified, as can insufflated carbon dioxide during minimally invasive surgical procedures. For surgical procedures with large areas of exposure, warmed solutions should be available for use instead of room temperature solutions. Intravenous (IV) solutions can also be warmed before administration.

Metabolism

Infants have a higher basal metabolic rate than adults, and it is greatest at 18 months. Most importantly, children younger than age 2 years have immature liver function; pharmacologic response is altered, and there is slower hepatic clearance, decreased hepatic enzyme function, and decreased protein binding. Medication distribution is different in neonates and infants compared with older children and adults because of an increased percentage of total body weight and extracellular body fluid. Infants have an immature blood-brain barrier and decreased protein binding, which results in an increased sensitivity to sedatives, opioids, and hypnotics.

Fluid Management

Renal function at birth is immature, and the ability of the kidneys to concentrate urine is limited, so the infant is much more prone to dehydration. Complete maturation of renal function occurs at about 2 years. Compared to an adult, a child has a higher body water weight, a higher body surface area, and an increased metabolic rate, resulting in increased fluid requirements per kilogram of body weight. Despite these significant points, it is also important to remember that the body weight of the child, the length of time without fluids, and surgical losses are the primary factors in the calculations of the child’s hydration needs.

Psychologic Development

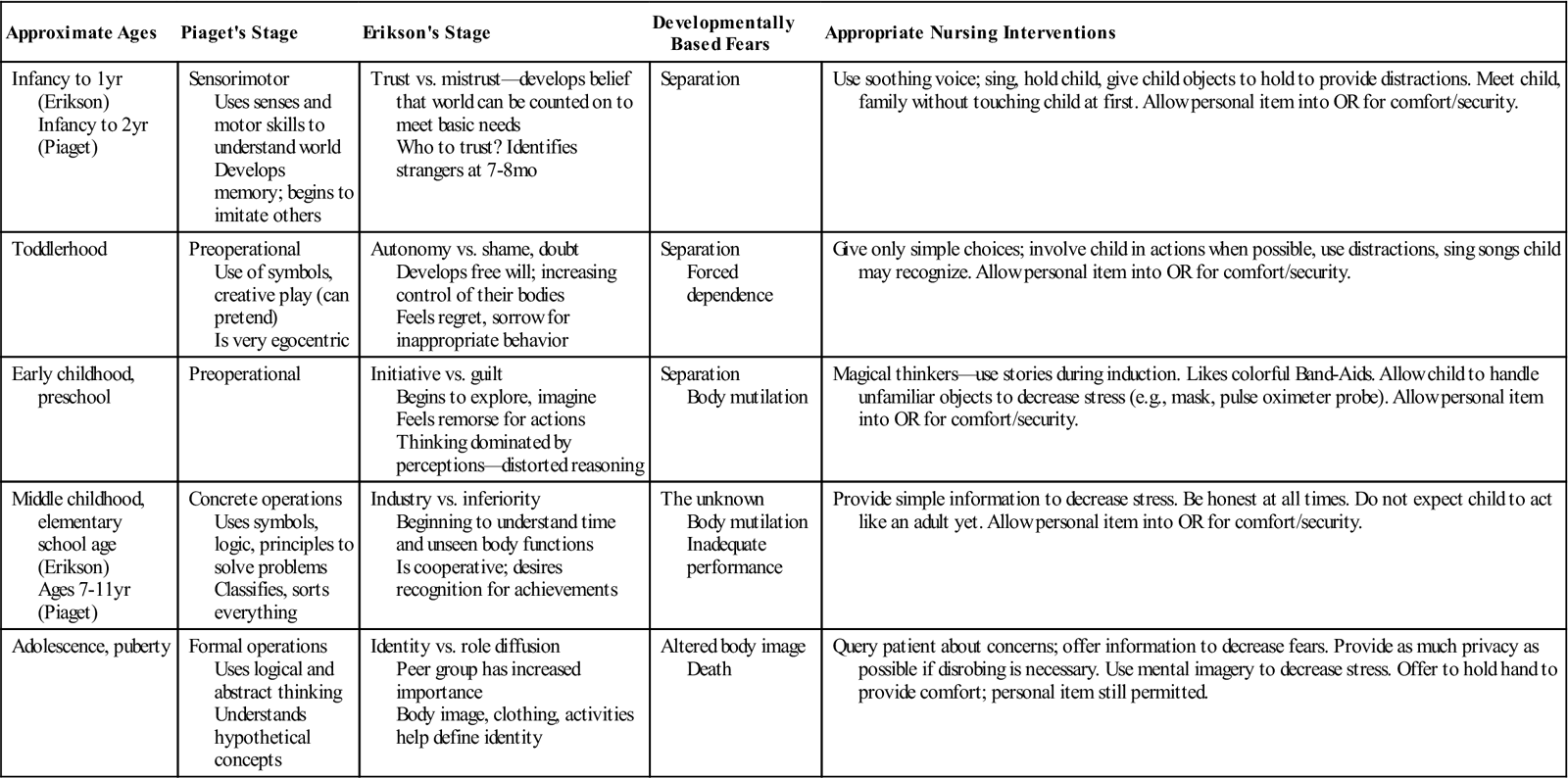

A child’s comprehension of and responses to the environment are based on developmental age. A key factor is that a child’s developmental age does not necessarily match the chronologic age. Nursing care should be tailored to the developmental age of the child to optimize the child’s ability to understand the situation, to minimize the child’s and family’s stress and anxiety, and to facilitate the development of a trusting and supportive medical relationship. The types of fears are also related to the child’s level of psychologic development. Predictable stages mean predictable behaviors. The stages of growth have been described from a variety of different aspects; Dr. Jean Piaget described the stages by changes in cognition and the ability to think, and Dr. Erik Erikson based the stages on psychosocial and emotional needs. Their work provides an excellent guideline for assessing the pediatric patient’s developmental level in order to use appropriate interventions (Table 26-1).

TABLE 26-1

| Approximate Ages | Piaget’s Stage | Erikson’s Stage | Developmentally Based Fears | Appropriate Nursing Interventions |

| Infancy to 1 yr (Erikson) Infancy to 2 yr (Piaget) | Sensorimotor Uses senses and motor skills to understand world Develops memory; begins to imitate others | Trust vs. mistrust—develops belief that world can be counted on to meet basic needs Who to trust? Identifies strangers at 7-8 mo | Separation | Use soothing voice; sing, hold child, give child objects to hold to provide distractions. Meet child, family without touching child at first. Allow personal item into OR for comfort/security. |

| Toddlerhood | Preoperational Use of symbols, creative play (can pretend) Is very egocentric | Autonomy vs. shame, doubt Develops free will; increasing control of their bodies Feels regret, sorrow for inappropriate behavior | Separation Forced dependence | Give only simple choices; involve child in actions when possible, use distractions, sing songs child may recognize. Allow personal item into OR for comfort/security. |

| Early childhood, preschool | Preoperational | Initiative vs. guilt Begins to explore, imagine Feels remorse for actions Thinking dominated by perceptions—distorted reasoning | Separation Body mutilation | Magical thinkers—use stories during induction. Likes colorful Band-Aids. Allow child to handle unfamiliar objects to decrease stress (e.g., mask, pulse oximeter probe). Allow personal item into OR for comfort/security. |

| Middle childhood, elementary school age (Erikson) Ages 7-11 yr (Piaget) | Concrete operations Uses symbols, logic, principles to solve problems Classifies, sorts everything | Industry vs. inferiority Beginning to understand time and unseen body functions Is cooperative; desires recognition for achievements | The unknown Body mutilation Inadequate performance | Provide simple information to decrease stress. Be honest at all times. Do not expect child to act like an adult yet. Allow personal item into OR for comfort/security. |

| Adolescence, puberty | Formal operations Uses logical and abstract thinking Understands hypothetical concepts | Identity vs. role diffusion Peer group has increased importance Body image, clothing, activities help define identity | Altered body image Death | Query patient about concerns; offer information to decrease fears. Provide as much privacy as possible if disrobing is necessary. Use mental imagery to decrease stress. Offer to hold hand to provide comfort; personal item still permitted. |

Modified from Taylor E: Providing developmentally based care for toddlers, AORN J 87(5):992–999, 2008; Taylor E: Providing developmentally based care for school-aged and adolescent patients, AORN J 90(2):261–269, 2009; Stages of social-emotional development in children, available at http://childdevelopmentinfo.com/child-development/erickson.shtml. Accessed February 1, 2013.

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

Assessment

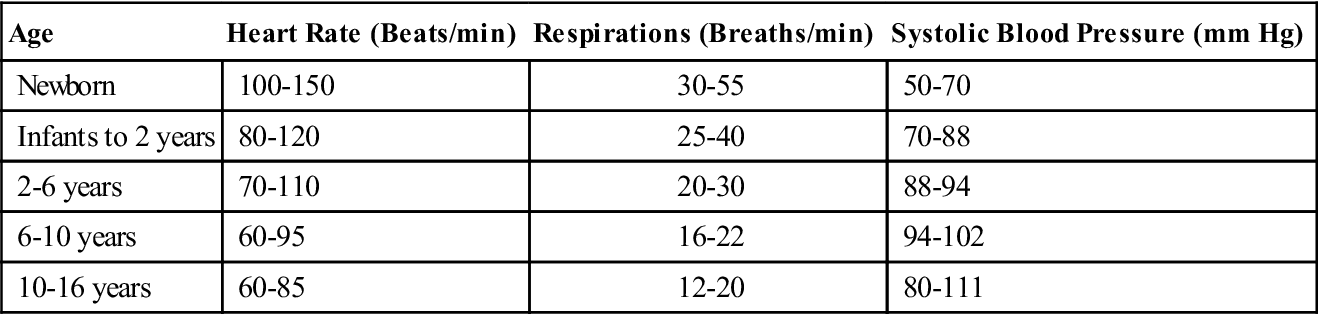

The initial patient assessment provides information necessary to develop a plan of care specific to the needs of each pediatric patient related to age, developmental level, and diagnosis. The unique aspects of care of the pediatric surgical patient revolve around the fact that the child is constantly growing and changing. The perioperative nurse must have a good understanding of the normal physical and psychologic parameters for pediatric patients and be able to recognize and act on deviations from these parameters. Table 26-2 presents normal vital sign ranges for infants and children.

TABLE 26-2

| Age | Heart Rate (Beats/min) | Respirations (Breaths/min) | Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) |

| Newborn | 100-150 | 30-55 | 50-70 |

| Infants to 2 years | 80-120 | 25-40 | 70-88 |

| 2-6 years | 70-110 | 20-30 | 88-94 |

| 6-10 years | 60-95 | 16-22 | 94-102 |

| 10-16 years | 60-85 | 12-20 | 80-111 |

From Ball JW, Bindler RC: Principles of pediatric nursing: caring for children, ed 5, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2012, Pearson Prentice Hall.

In addition, the perioperative nurse must be familiar with normal growth and developmental factors for each age group. During any given day, the perioperative nurse may care for a variety of pediatric patients ranging from neonates through adolescents. In some instances, children undergoing an ambulatory surgical procedure may visit the OR complex and ambulatory surgery area with their families 1 to 2 weeks before surgery, depending on the child’s developmental level and the availability of a preoperative pediatric education program. If the child has a complex medical history or an extensive surgical procedure is planned, the child and family members will meet with a member of the anesthesia team during this advance visit. A tour may be provided by a child life specialist (Patient and Family Education), along with pictures and age-appropriate explanations of what the child will see and experience. Visiting before the day of surgery can help decrease the anxiety related to the novelty of the experience.

Occasionally the child’s history and physical, surgical consent, and any necessary tests or lab work are done in advance in the surgeon’s office setting, and the child and family have no introduction to the surgical experience until the day of surgery. Information related to the child’s scheduled procedure is either sent home with the family from the surgeon’s office or mailed to the family the week before the surgery is scheduled. The surgical facility contacts the family the day before surgery to inform them when the child should arrive at the facility and to review preoperative eating and drinking instructions. In these instances, the initial interview performed by the perioperative nurse is especially crucial to provide a thorough, documented assessment of the child’s growth (height and weight), current physical status (vital signs, heart and breath sounds, skin integrity), current medication history, allergies, nothing by mouth (NPO) status, recent illnesses, current medical concerns, and behavioral responses to the interview process. The perioperative nurse confirms the intended surgical procedure with the child and family as it is written on the surgical consent as well as their understanding of the operation. This information is critical to the intraoperative nursing team’s plan of care during the surgical procedure.

Children may undergo surgery at ambulatory surgery facilities or in a hospital setting. Certain criteria must be met for children to qualify for surgery at an ambulatory facility (Ambulatory Surgery Considerations). Children who are inpatients may be visited by a perioperative nurse in the hospital on the day before surgery. The nurse reviews the patient’s chart, giving particular attention to the patient’s age, developmental level, diagnosis, and intended surgical procedure. Current nursing diagnoses and the ongoing plan of care are examined. A discussion with the primary nurse can facilitate data collection, assist in providing continuity of care, and provide the perioperative nurse with information regarding preoperative education previously provided. The perioperative nurse can meet the child and any family members present at the time of the visit. The interview can be used to gather information helpful to developing the intraoperative plan of care and to decreasing the anxiety related to the child’s impending surgery by providing a familiar face on the day of the procedure. The focus of this visit is to discuss the perioperative process, not always to provide preoperative education regarding the surgery. In pediatric centers in the inpatient setting, preoperative education may be provided by the primary nurse, child life therapist, or clinical nurse specialist. During the preoperative visit the perioperative nurse can explain, at a developmentally appropriate level, what the child will experience in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of care. The perioperative nurse may briefly describe the roles of various staff members who will be a part of the team responsible for the child’s care in the OR. Common concerns that families express are the length of time that they will be separated from their child and their child’s pain management. Explanations to children should be provided within a developmental framework, taking into account each child’s cognitive and psychosocial abilities. Medical play items, audiovisual aids, puppets, and photographs are all helpful in the education process.

The perioperative nurse who will be participating in the intraoperative care of the child will review the patient’s information and meet with the patient and the family before the child is transferred to the OR. In addition to reviewing the documentation, the nurse validates the patient’s identification using two patient identifiers, confirms that the surgeon has marked the child’s surgical site per institutional protocol, and seeks verbal verification from the patient, parent, or legal guardian about the scheduled procedure, making sure that it matches what is written on the surgical consent (Figure 26-1). If implants are to be used, availability must be confirmed before the patient’s transport to the surgical suite. Frequently children will be given a premedication 20 to 45 minutes before their transportation to the OR. A premedication such as midazolam can greatly decrease a child’s anxiety, minimizing the stress of separation for both child and family. The surgeon and anesthesia provider will each meet with the child and family, usually while the OR is being prepared for the patient. The perioperative nurse will assess the child’s psychologic state, review the intended surgical procedure with the child and family, and ensure that they have no additional questions or concerns. A final communication among the anesthesia provider, surgeon, and nursing staff for the room confirms the team’s state of readiness for the delivery of care before the nurse transports the child to the OR.

Informed Consent.

Informed consent must be obtained prior to administrating anesthesia or performing surgery. For children younger than age 18, consent must be obtained from one of the following individuals: a legal parent (biologic parent whose parental rights have not been terminated) or an adoptive parent who has completed the adoptive process. Foster parents of children in the custody of a child and youth agency (CYA) are not permitted to give consent. Rather, consent should be obtained from the CYA social worker. Legal guardians should be encouraged to bring any supporting documentation of legal guardianship or ability to consent for the child’s medical care on the day of surgery. Perioperative nurses should review the chart for documentation of legal guardianship and ensure that each document is signed by the appropriate individual.

When emergency situations arise and the need for treatment is immediately necessary to prevent serious or permanent impairment of the patient’s health or to preserve the life of a patient, surgery may be performed without consent of the legal parent. In the event that a legal parent is unable to be located or unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, a court order may be obtained to permit treatment. A pediatric patient who is an emancipated minor (e.g., legally under the age of consent but recognized as having the legal capacity to consent), can give valid consent for him- or herself. It is important for children to develop a trusting relationship with medical professionals and that these older children are in agreement (within their developmental capabilities) with their family’s decision regarding surgery. Risk management and legal departments can assist in clarifying questions or conflicts specific to informed consent.

Child Abuse and Neglect.

Perioperative nurses are obligated to screen all pediatric patients for abuse or neglect. Child abuse and neglect results from any of the following: physical injury, sexual abuse or exploitation, negligence or maltreatment (Betz and Sowden, 2008). Child abuse is found in all segments of society, crossing cultural, ethnic, religious, socioeconomic, and professional groups. The perioperative nurse is in a unique situation to assess for the presence of abuse because the patient will be disrobed in the OR. Box 26-1 lists the clinical manifestations of child abuse. Every state has a child abuse law that dictates legal responsibility for reporting abuse and suspicion of abuse, and nurses are mandated reporters. Failure to report suspected child abuse could result in a fine or other punishment, according to individual statutes (Betz and Sowden, 2008).

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses related to the care of pediatric patients undergoing surgery might include the following:

• Anxiety related to separation from family and friends

• Fear related to developmental level (fear of the unknown, fear of painful procedures and surgery)

• Risk for Infection related to surgical intervention and other invasive procedures

• Risk for Imbalanced Fluid Volume related to invasive surgery and accompanying blood loss

Outcome Identification

Perioperative nursing care is predicated on relevant nursing diagnoses and their corresponding desired outcome. Outcomes should be measurable with criteria by which to judge their attainment. Thus for the desired outcome, “The patient will demonstrate some ability to manage anxiety,” measurable criteria (e.g., the child will have posture, facial expressions, gestures, and activity levels that reflect decreased anxiety and will demonstrate increased focus) might be identified.

Outcomes identified for the selected nursing diagnoses for the pediatric patient could be stated as follows:

Planning

Assessment data, combined with information about the planned surgical procedure, enable perioperative nurses to anticipate requirements for surgical positioning, instrumentation, equipment and supplies, medications, and activities necessary for the provision of safe, competent care for the pediatric patient. Knowledge of the child’s developmental level allows the nurse to plan her or his approach and interactions with the child and family (Figure 26-2). The perioperative nurse identifies criteria appropriate to the child and surgical setting for each of the desired outcomes (Sample Plan of Care). A Sample Plan of Care is shown for the pediatric patient on pages 1014-1015.

The perioperative nurse must also develop a trusting relationship with the child and his or her parents, family, or legal guardians. The nurse must explain the events of surgery in a way that allows the child and accompanying adults to better understand what to expect on transfer to the OR (Patient-Centered Care).

Implementation

Age-appropriate communication is important in implementing the pediatric nursing plan of care. Implementation begins during the perioperative nursing assessment and continues through discharge to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) or other area. The presence of a parent during much of the preoperative period, including during anesthesia induction in the OR and after anesthesia emergence in the PACU, can help decrease anxiety for both young children and their families and facilitates family-centered care (Evidence for Practice).

Infants, reliant on family to meet their basic needs, are difficult to pacify when NPO for surgery. The facility should provide rocking chairs, pacifiers, warm blankets, and simple distractions such as music or toys. Preoperative teaching should include telling the family to provide fluids for the infant until the deadline for NPO status. Unnecessary delays should be avoided at all costs. Parents may need reassurance and support during the period immediately before surgery.

The toddler or preschooler fears parental separation and abandonment. Toddlers fear, among other things, strangers, the dark, and machines. They attribute lifelike qualities to inanimate objects, believing that the objects, like them, have feelings. Thus a blood pressure cuff that squeezes the child’s arm may be perceived to be doing so because it is angry with the toddler. Toddlers may also believe that their body is held together by their skin; anything that violates the skin integrity is feared. For this reason, bandages are very important. Toddlers and preschoolers interact with the environment using their senses. To integrate this into the patient’s care, the perioperative nurse should give the toddler the opportunity to touch and play with objects that he or she will encounter. An example is to give the child a small anesthesia mask to put on his or her teddy bear. Sensory information should be provided in a soft, gentle voice (i.e., what the toddler will see, feel, touch, and hear). A security object is extremely comforting. The OR should be quiet; background noise should be controlled. Instruments that are frightening should be kept from view. To allow quick induction of anesthesia the toddler should be transferred into the surgical suite when the room and staff are completely prepared.

The school-age child may still perceive hospitalization or surgery as a punishment but can evaluate painful intrusive actions in terms of logical function (e.g., getting an IV line hurts, but then I can get medicine in it to make me feel better). Feelings of inadequacy may be associated with something the child thinks he or she should be expected to do or know. Fear of body injury or mutilation, loss of control, and fear of the unknown characterize this developmental stage. These children benefit from simple, concrete explanations in familiar terms; a book or other teaching aid can be helpful. The concepts of time and unseen body functions can now be incorporated in the explanations. The child should be allowed to make choices when possible (e.g., letting the child decide in which hand to place the IV line or which flavor to add to the anesthetic mask).

Adolescents may fear altered body image, peer rejection, disability, and loss of control or status. The fear of death is more prevalent in this age-group than any other, and adolescents may find explanations of monitoring and safety measures reassuring. They need as much privacy as possible, and their attempts to be independent should be respected (e.g., walking into the OR instead of being wheeled in on a stretcher if the patient has not been sedated). The adolescent may not wish to show any fear; questions might not be asked while the parents are present. Information and explanations should be provided as reasonably and truthfully as possible. If appropriate, some choices should be allowed, such as wearing underwear to the OR. Patient care procedures that violate privacy, such as hair removal, skin preparation, or insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter, should be conducted after the patient is anesthetized.

Key points in providing perioperative care to pediatric patients include remaining alongside the child until the child is anesthetized, keeping the room quiet during induction, accepting a child’s need to express fear and fearful behaviors (e.g., crying), and using simple words without double meanings to explain care. Security objects should remain with the child until induction has been completed. A child’s behavior during induction is likely to be the same during emergence; thus all attempts should be made to provide calm, reassuring care. Parents should be alerted to delays in the surgery schedule; in some instances, the child may be allowed to have fluids if the surgery is delayed by several hours.

Implementing the nursing plan of care includes continual reassessment of the patient’s needs as well as the efficient execution of activities that facilitate the surgical intervention. Remaining with the child during induction, positioning, and prepping the surgical site; creating and maintaining a sterile field; collecting, documenting, and disposing specimens; and administering medications are all part of helping to provide a safe environment for the pediatric surgical patient. Making sure that the pediatric patient’s family receives regular updates of the child’s status is also a part of the perioperative nurse’s responsibilities and will decrease their anxiety and help foster a sense of trust in the healthcare professionals caring for their child.

Instrumentation.

The same types of instruments used in adult surgery are used in pediatric surgery. However, pediatric instruments are usually shorter, have more delicate or less pronounced curves, and are smaller. A complete range of instrument sizes is necessary to make the appropriate size available to each child because pediatric patients can range in size from less than 1 to more than 100 kg. Fewer instruments are normally required because incisions in children are shorter and shallower than those in adults. Use of basic instrument sets, grouped according to types of surgery performed (e.g., minor, major), facilitates instrument counts. Instrument sets may also be grouped according to categories of patient size (e.g., infant, pediatric, adolescent, and adult). These sets are easily adapted to the patient’s needs as well as the surgeon’s preferences and eliminate unnecessary instruments from the sterile field.

Sutures.

A variety of sutures are used with the pediatric population because of the wide range of patient size; needles from size 0 to 7-0 are routinely stocked. Both absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures on cutting and tapered needles are used. The most frequently used sizes are 3-0 to 5-0 with  – and

– and  -circle needles. Staples, both pediatric and regular sizes, are occasionally used. Many skin incisions are closed with subcuticular techniques, over which adhesive strips or cyanoacrylate glue is then applied. The use of tape to apply dressings is done conservatively because of the delicate nature of children’s skin; frequently, either a small transparent or an elastic net dressing is used to hold gauze dressings in place.

-circle needles. Staples, both pediatric and regular sizes, are occasionally used. Many skin incisions are closed with subcuticular techniques, over which adhesive strips or cyanoacrylate glue is then applied. The use of tape to apply dressings is done conservatively because of the delicate nature of children’s skin; frequently, either a small transparent or an elastic net dressing is used to hold gauze dressings in place.

Anesthetic Considerations.

Anesthesia is approached differently in pediatric patients than it is in adults. The equipment and supplies are scaled down to match the size of the patient, and different anesthesia circuits and delivery systems may be used. Adult facilities that provide anesthesia to pediatric patients should consider developing a mobile pediatric intubation cart that houses the appropriate sized equipment and devices necessary to care for the anesthetized child.

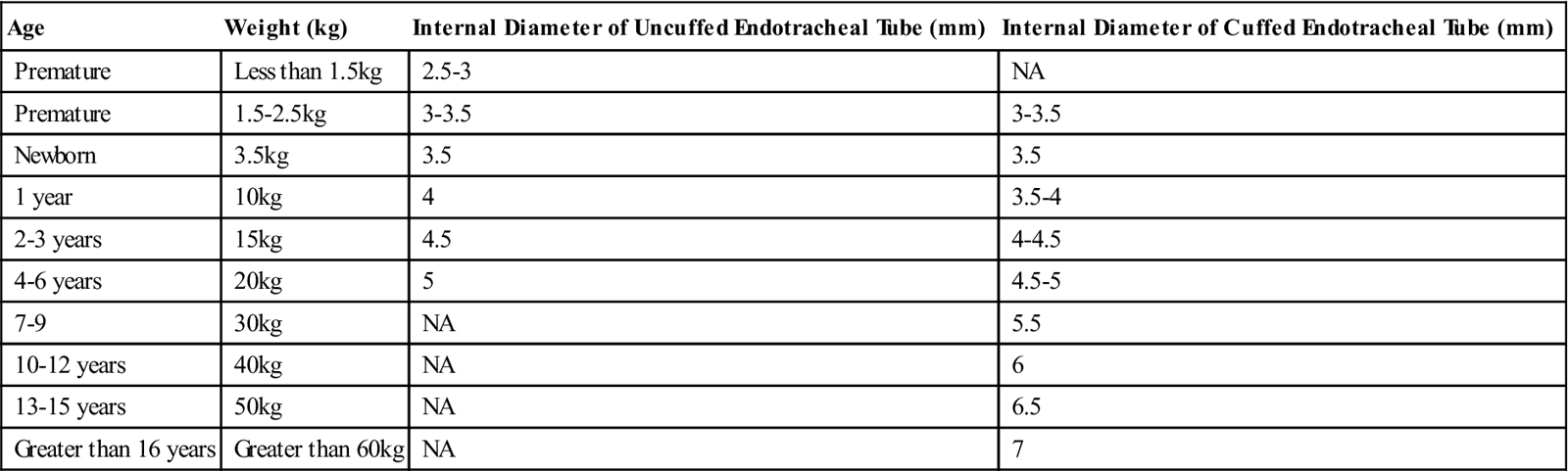

The most common technique used in the pediatric population is a general inhalational anesthetic administered by facemask, laryngeal airway, or endotracheal tube. Selection of the endotracheal tube involves several considerations; the tube must be large enough to permit ventilation but small enough to minimize damage to the trachea while maintaining a seal to prevent aspiration. Table 26-3 provides a guide to choosing endotracheal tube sizes for pediatric patients. Depth of insertion to the lip is calculated by multiplying the inner diameter of the endotracheal tube by 3 (Gottlieb and Andropolous, 2011).

TABLE 26-3

Recommended Sizes of Oral Endotracheal Tubes Based on Age and Weight

| Age | Weight (kg) | Internal Diameter of Uncuffed Endotracheal Tube (mm) | Internal Diameter of Cuffed Endotracheal Tube (mm) |

| Premature | Less than 1.5 kg | 2.5-3 | NA |

| Premature | 1.5-2.5 kg | 3-3.5 | 3-3.5 |

| Newborn | 3.5 kg | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| 1 year | 10 kg | 4 | 3.5-4 |

| 2-3 years | 15 kg | 4.5 | 4-4.5 |

| 4-6 years | 20 kg | 5 | 4.5-5 |

| 7-9 | 30 kg | NA | 5.5 |

| 10-12 years | 40 kg | NA | 6 |

| 13-15 years | 50 kg | NA | 6.5 |

| Greater than 16 years | Greater than 60 kg | NA | 7 |

Modified from Gottlieb EA, Andropolous DB: Pediatrics. In Miller RD, Pardo MC, editors: Basics of anesthesia, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Churchill Livingstone; Stackhouse RA: Airway management. In Miller RD, Pardo MC, editors: Basics of anesthesia, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Churchill Livingstone.

Microdrip IV tubing and burettes are commonly used to avoid the administration of excess fluids in pediatric patients younger than 8 years, and only 500-mL bags of IV solution are used. The patient’s IV line is usually started in the OR after induction with mask anesthesia, depending on the patient’s diagnosis and medical history. Patients who require emergency surgery who have not been NPO; have increased intracranial pressure, an unusually difficult airway, or neuromuscular disease; or have been diagnosed with malignant hyperthermia require an IV placement before anesthesia induction. If the IV line is started before induction, measures should be taken to lessen the discomfort, such as an intradermal injection of 1% buffered lidocaine or saline at the site or the application of topical anesthetic creams. If possible, the surgical team should allow the child the option of sitting up or lying down during IV placement; if developmentally appropriate, hold the child’s hand and tell the child about each step in the placement of an IV line.

Preoperative sedation is generally accomplished by the oral administration of midazolam. Midazolam is the most commonly used pediatric premedication in the United States and can be given orally, nasally, rectally, intramuscularly, or intravenously. Oral midazolam should be administered in a flavored base to mask the bitter taste. Relaxation is noted 15 to 45 minutes after administration; the child should be kept in a safe, observable environment after being medicated. Other agents used for premedication include fentanyl and, infrequently, ketamine.

Depending on institutional policy, a parent may be present during induction to comfort the child and decrease the child’s anxiety. The perioperative nurse should provide the parent an explanation of how the OR will appear and who will be present in the OR, how the child’s anesthesia induction will be performed, and how the child will appear as the anesthetic takes effect. An additional staff person, such as a parent services’ provider or child life therapist, should be present to escort the parent to and from the OR so that the perioperative nurse can focus on providing care for the patient once the child has been anesthetized.

Distraction methods during the induction of anesthesia can help minimize a child’s stress and anxiety. Singing softly, telling a story, and, for the older child, providing a relaxing mental image are effective diversion techniques.

Malignant hyperthermia (MH), although very rare, may be more prevalent in the pediatric population as a result of the administration of inhalational anesthetics and succinylcholine. In addition, physiologic conditions present in some pediatric patients are associated with a higher risk of MH. These conditions include congenital myopathies such as central core disease and King-Denborough syndrome (Gottlieb and Andropolous, 2011). Careful assessment of family history is essential to identify patients at risk for developing MH. The management of an MH crisis is described in Chapter 5.

Pain Management.

In the past, many common fallacies existed about pain in the pediatric population. Some of these mistruths were that infants do not feel pain; children have better pain tolerance than adults; children cannot tell the healthcare provider where they hurt; children always tell the truth about pain; children become accustomed to pain or painful procedures; and narcotics are more dangerous for children than they are for adults. Research into this important area has revealed that infants do demonstrate behavioral and physiologic indicators of pain. Compared with adults, children have less pain tolerance; their pain tolerance increases as they mature. Children are able to indicate pain, and children as young as 3 years can use pain-rating scales. Often children may not admit to having pain; they may believe that others know how much they hurt, or they fear receiving an injection. Children may also feel that pain and suffering are punishment for some misdeed, or they may not know what the word pain means. Children do not become accustomed to pain or painful procedures. They actually may demonstrate increased behavioral signs of pain with repeated procedures. Many factors, such as developmental level, culture, coping ability, temperament, and activity levels, influence the behavioral manifestations of pain exhibited by the patient. Narcotics are no more dangerous for children than they are for adults and are not excluded as a treatment modality. The evaluation of a pediatric patient’s level of pain is performed using a variety of assessment tools (pain scales) that are based on the age and developmental level of the child. Often these scales are tested for reliability and validity. In infants and nonverbal children, evaluation is based on physiologic changes and observation of behaviors. Children with verbal skills are able to articulate pain. One assessment strategy to use with pediatric patients is the QUESTT method:

Evaluate behavior and physiologic changes.

Secure the parents’ involvement.

Take cause of pain into account.

Questioning the child provides the most reliable indicator of pain. Children may not be familiar with the word pain and may be more comfortable with words like “ouch,” “hurt,” or “owie.” It may also be helpful to ask the child to point to where it hurts. The FACES pain scale uses cartoon faces with a variety of expressions ranging from happy to crying. The child selects the face that best describes his or her pain (see Chapter 10). The Oucher scale has a numeric component and a component similar to the FACES scale but uses actual photographs of children. The adolescent pediatric pain tool (APPT) is a line drawing of a body; the child marks the drawing where he or she has pain. Other tools include Likert-type scales rating pain on a score of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain) or incorporate several components of pain assessment (subjective and objective data).

Physiologic indicators of pain, such as increased blood pressure, respirations, and heart rate and restlessness, are the same for children as for adults but may not be as reliable, except in neonates and nonverbal children. These indicators may also reflect anxiety or fear and should not be the sole indicator used to determine pain. Children may also tug or hold painful areas or show preference to a painful extremity.

Parental involvement in pain management is important. Parents know their child’s normal behavior and can provide input into the behaviors being exhibited in the perioperative setting. Parents should be queried about the child’s previous experiences with pain and be taught the nonverbal behaviors that may indicate pain.

Nurses should investigate all complaints of pain or discomfort and be sensitive to behavioral and nonverbal cues to determine treatment. Postoperative pain should be assessed after all surgical procedures, regardless of their nature. It is also critical to assess and document the child’s response to the interventions provided for relief of pain.

Effective pain management requires a willingness to use a variety of methods and modalities to achieve optimal results. Pharmacologic methods include the administration of analgesics, both narcotic and non-narcotic. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is an option for children. Children as young as 5 years have the cognitive and physical capabilities to successfully use this modality with appropriate instruction and support (Wetzel, 2011). Nonpharmacologic methods include distraction, relaxation, guided imagery, behavioral contracting, and cutaneous stimulation. Nonpharmacologic methods should never be used as substitutes for appropriate medication administration but instead to enhance pain management.

Evaluation

The perioperative nurse evaluates care provided throughout the perioperative period. At the conclusion of the surgical intervention, the skin is inspected, especially at dependent pressure points and at the site of the electrosurgical dispersive pad. Inspection is carried out to detect any reddened, irritated areas or evidence of compression injury. If povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate preparations were used for skin prep, the area needs to be checked for any signs of chemical irritation. The patient’s temperature is reassessed. The cardiopulmonary status is closely monitored as the child emerges from anesthesia. The perioperative nurse should assist the anesthesia team during emergence, remaining at the patient’s bedside. Warm blankets are provided; hydration status is evaluated as replacement fluids continue to be administered, and fluid output is noted. The child is transferred to and positioned on the stretcher, crib, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) warmer, or ICU bed; the airway and respiratory effort are reassessed before departing the OR. Tubes, IV lines, drains, and drainage devices must be carefully protected during the move from the operating bed. Supplemental oxygen is always given during transport from the OR to the PACU for pediatric patients.

The perioperative nurse provides a hand-off report to the PACU nurse, focusing on the condition of the child, the response to surgery and anesthesia, the presence of catheters and drains, the quality and amount of wound drainage, a description of the dressings applied, and any special needs. Part of this report should focus on the outcomes established in the perioperative plan of care. For the plan of care presented in this chapter, they might be as follows:

• The patient demonstrated decreased anxiety.

• The patient responded in an age-appropriate manner to comfort measures and exhibited decreased fear.

• The patient remained hemodynamically stable and did not exhibit fluid volume deficit.

• The patient’s temperature was maintained in the desired range during the perioperative period.

The perioperative nurse may receive further feedback on the child’s progress after the child is discharged from the PACU; information may be relayed by the surgeon, unit nurse, or anesthesia provider. This type of informal feedback helps the perioperative nurse collect additional data regarding effectiveness of the plan of care, providing information about the achievement of identified outcomes.

Patient and Family Education and Discharge Planning

Patient and family teaching varies significantly based on the type of surgery performed. Some hospitals provide special preoperative teaching and hospital tours for pediatric patients and their parents to help them prepare for the surgical experience. Sometimes information is discussed with the child and family at the time of the office visit, when the surgery is scheduled. For same-day procedures, the day-surgery nursing staff might teach postoperative care immediately before patient discharge. Basics of postoperative care are reviewed with the parents at this time. In some cases, written material may be provided (Box 26-2). Parents should be advised to be alert for certain signs and symptoms during the postoperative recovery period that could indicate an infectious process, such as fever, pain, nausea, redness around the incision area, drainage from the wound, or difficulty breathing. These signs and symptoms may develop days or even weeks after surgery. It is important that parents understand the necessity of not ignoring any of these signs and symptoms and of reporting them to the surgeon promptly so that an early diagnosis can be made and treatment prescribed. Although discharge information depends on the type of surgery performed, it typically includes recommendations about activity restrictions, return to school or daycare, wound care, bathing or showering, diet, and follow-up appointments. The printed discharge instructions are reviewed with the parents, and their understanding is verified. This time should provide the family with an opportunity to ask questions or seek clarification of the instructions. Phone numbers for the surgeon and the main hospital are provided in case the family has concerns or questions during the child’s recovery period at home. An appointment for the child’s follow-up visit may be made before discharge, or the parents are instructed to call the physician’s office to schedule an appointment.

Surgical Interventions

As mentioned, children require surgery for congenital malformations, an acquired disease, or trauma. The field of pediatric surgery is further subdivided into all the specialties. Several surgical procedures that may be designated pediatric are presented in previous chapters of this text under particular specialty headings. The surgical interventions presented here represent procedures that are most commonly performed on children.

Vascular Access

Vascular access in pediatric patients may be established intraoperatively for short-term (weeks) or long-term (months, years) use. Examples of short-term use include peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC lines) for antibiotic therapy. Central venous lines or implanted ports are placed for long-term access to provide parenteral nutrition, chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, or multiple IV access lines for the critically ill patient. Neonates and children born at low birthweights are at highest risk for catheter-associated infections as a result of their compromised immune status (Curry et al, 2009). National and consumer organizations are exerting pressure on hospitals to implement practices aimed at reducing and eliminating catheter-associated infections in all patients (Wheeler et al, 2011).

Central Venous Catheter Placement

The preferred site of placement for central venous access is the external jugular vein. The internal jugular vein may be chosen if the external jugular vein has been used or is too small. From the cannulation site the catheter is tunneled under the skin about 5 to 10 cm. This is done to inhibit contamination of the bloodstream from frequent dressing changes. Subcutaneous ports are placed in a similar fashion. In cases in which the internal or external vein sites are unavailable, the catheter may be placed into the external iliac vein by way of a cutdown in the greater saphenous vein. In these cases, the catheter is tunneled into the abdominal wall.

Procedural Considerations.

The manufacturer’s instructions for handling and preparing the catheter must be followed. The catheter must not contact lint, glove powder, or other foreign matter. Before insertion the catheter is flushed and filled with heparinized saline (1 unit of heparin to 1 mL of saline) to prevent air bubbles from entering the circulatory system and to eliminate blood clots in the catheter lumen. Fluoroscopy is used to confirm proper placement of the catheter; lead shielding must be provided for patient and staff, with appropriate warning signs placed on room doors. The use of a lead shield for the patient should be documented in the perioperative record.

The child is appropriately positioned as dictated by the site chosen for cannulation, and organs are protected with a lead shield. The area is prepped and draped.

Operative Procedure—External Jugular Vein Site

1. The surgeon uses a needle and syringe to puncture the external jugular and aspirates to confirm blood flow.

2. The syringe is removed from the needle, and a guidewire is fed through the needle into the vein. An intraoperative x-ray is taken to confirm correct position.

3. Once the position is confirmed, the surgeon makes an incision over the insertion site. A silver probe or tendon passer is used to create a tunnel beneath the skin to the desired exit site of the catheter. A second incision is made over the tip of the probe or passer.

4. The implantable end of the catheter is attached to the end of the passer or probe and pulled through the subcutaneous tunnel. The catheter is cut to a desired length.

5. The needle is removed from the vein, leaving the guidewire in place. An obturator is placed over the guidewire, and the wire is removed. The catheter is placed through the obturator into the vein, and an intraoperative x-ray is taken to confirm position.

6. The catheter is secured at the exit site on the chest wall with nonabsorbable sutures, flushed with a “super flush” of heparinized saline (10 units of heparin to 1 mL of saline in children younger than 12 months or 100 units of heparin to 1 mL of saline in children older than 12 months), and clamped.

7. An occlusive transparent dressing is placed over the catheter site. The catheter is coiled under this dressing to avoid tension on the line and accidental displacement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree