Inflamed (Red) Eye

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• INTRODUCTION

Patients presenting with redness in the visible portion of the eye is a common symptom in primary and urgent care practice. Nearly 6 million cases of acute conjunctivitis also known as “pink eye” are reported annually in the United States. Approximately 15% of adult patients suffer from allergic ocular conditions. Patients routinely present to the pharmacy with eye complaints. However, minority of causes of red eye can be treated with nonprescription products so the primary role of the pharmacist is referral to either primary, emergent, or specialty care. The most common specific causes of a red eye are (1) infectious (viral or bacterial); (2) allergic; and (3) “nonspecific,” which includes irritative. There are other conditions that can be confused with conjunctivitis, including some that need urgent or emergent management.

• RELEVANT ANATOMY

Location of the redness can be important so a brief review of eye anatomy is important. The term conjunctivitis means inflammation of the conjunctiva (singular) or conjunctivae (plural). The conjunctiva is usually described as having three parts, all of which are thin, transparent layers of mucous membrane. The most external and easily observable portion is that which overlies the white portion (sclera) of the eyeball itself. This is called the bulbar or ocular conjunctiva. It covers the entire sclera, but it does not cover the central anterior portion of the eyeball (the cornea). That is, it extends onto the eyeball up to, but not beyond, the limbus. The limbus is the union of the cornea and the sclera and a conjunctivitis limited to the limbus is an important clue to more serious cause of a red eye. When the bulbar conjunctiva is normal (not inflamed), it cannot be differentiated from the sclera beneath it, because it is clear. Another portion of the conjunctiva, visible if the eyelids are inverted, covers the inner linings of both upper and lower eye lids (the palpebrae). This portion of the conjunctiva is called the palpebral or tarsal conjunctiva. There is a third portion of the conjunctiva that is difficult to visualize, because of its anatomic location. This portion is located at the fornix, which is the communication between the palpebral and bulbar conjunctivae. In practical terms, conjunctivitis can be bulbar (the lining over most of the eyeball) or palpebral (the linings inside the eye lids) or both. The pink or red coloration is due to increased visualization of blood vessels in the conjunctivae due to vasodilation of the vessels. There are numerous possible causes of this increased vasodilation, but in general it is usually due to either irritation or inflammation. Inflammation of the surface of the cornea is known as keratitis and keratoconjunctivitis is inflammation of both the conjunctiva and the corneal surface.

• DIAGNOSIS

Elements of Evaluation of Eye Conditions That Indicate Urgent or Emergent Referral

Since there are few eye conditions that can be successfully treated with over-the-counter (OTC) products, the pharmacist will end up referring most patients. More importantly some patients present to the pharmacy to attempt to self-treat eye problems that may cause permanent loss of vision without immediate referral and treatment. Therefore, it is very important that pharmacists are aware of signs and symptoms that indicate serious eye problems. The following findings should always be a reason to advise the patient to see an eye-care specialist, usually on an emergent basis. These are findings that are not caused by simple conjunctivitis or other non-sight-threatening conditions (Table 14.1).

| TABLE 14.1 | Symptoms in Inflamed Eye Requiring Immediate Referral (May incur visual loss if not seen immediately) |

1. Pain in the eyeball itself Pain in the eyeball itself is far worse than the gritty sensation some patients with common forms of conjunctivitis have. Any suggestion of true eyeball pain is a reason for emergent referral. This symptom indicates a severe vision-threatening problem regardless of etiology.

2. Significant change in vision (not corrected by removal of any episodic discharge) This is mostly a subjective manifestation, but may be partly objective if a crude visual acuity test can be done having the patient read newsprint at arm’s length, presuming the patient’s baseline ability to do this is known. True visual impairment is an indication of a severe, possibly vision-threatening problem.

3. Photophobia (extreme sensitivity to light) Significant, severe, or persistent photophobia is another warning symptom. However, due to the primarily subjective nature of this complaint, it is more difficult to evaluate. Photophobia is extreme light sensitivity. Most people dislike a flashlight suddenly shone into their eyes and a typical reaction is to close the eyes, look away, or otherwise shield the eyes. However, when the patient is continuously bothered by the usual amount of ambient light present indoors in most homes and businesses, this is abnormal. However, even when this is present to a pathologic degree, removal of the light, that is, moving the patient to a darkened room, will alleviate the discomfort. In the darkened setting, the patient will be able to open the eyes and keep them open. True photophobia is usually an indication of serious uveal tract or possibly other serious ophthalmic disorder. The uveal tract consists of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Its structures extend from the iris, just under the cornea (near the anterior pole of the globe) to near the optic nerve at the posterior pole of the globe. A rather long list of potentially serious, vision-threatening problems can cause inflammation of the uveal tract (uveitis). Patients demonstrating this symptom should be referred to an eye-care specialist immediately. Not infrequently these conditions accompany an autoimmune arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis.

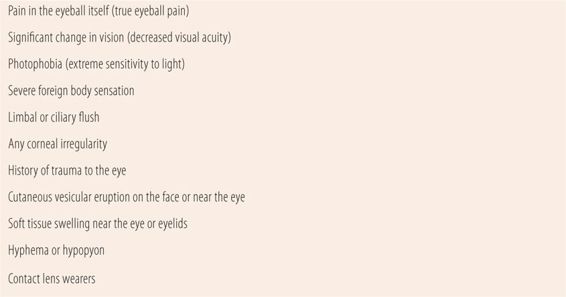

4. Severe foreign body sensation (eye shielded even without light shining in) Eye problems that cause a significant amount of foreign body sensation may be associated with corneal inflammation due to irritation, infection, or damage. This corneal inflammation, known as keratitis, has both subjective and objective components. The most helpful symptom that suggests keratitis is a severe foreign body sensation. The patient will complain of the feeling of “something in the eye” and as a result, will have difficulty opening and especially, keeping open the affected eye. The eyelids will be squeezed together, so as to close the eye. The patient will usually complain of severe discomfort, and perhaps express it as true pain. The eye will remain closed even in a darkened room. The patient may appear to shield the affected eye from light, but even when placed in a darkened room, they are reluctant to open the eye. The patient will generally resist even gentle attempts to open the eye by separating the lids. If the eye can be opened slightly in a darkened environment, shining a light into the eye usually does not worsen the situation, unless the patient is also experiencing photophobia. Appreciate that severe foreign body sensation is distinct from true photophobia. Objectively, there may be a small scratch or ulcer, which is not always visible on inspection with a penlight. However, it may have progressed to a defect in the cornea that is visible. Also if the cornea is anything except completely clear, there is some abnormality present. To confirm the presence of corneal damage, infection, inflammation, or ulceration, a fluorescein stain is conducted. Either an eye drop or an impregnated strip is placed in the eye. Then allow the dye to distribute over the corneal surface. The external eye is then examined with a blue light (cobalt blue or Wood lamp) via a magnifying binocular slit lamp. Lesions in the cornea clearly stand out as blue to green images. Figure 14.1 shows the typical dendritic pattern lesion of herpes simplex keratitis outlined by fluorescein stain. There are numerous possible causes of keratitis, all of which require referral, to an eye-care specialist, on an emergent basis.

FIGURE 14.1 Herpes simplex keratitis. A large dendritic lesion after fluorescein staining. The patient had been diagnosed with “pink eye” in a prior visit. SOURCE: photo contributor: Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS. Reproduced with permission from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman, RJ. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2010. Fig. 2-37. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

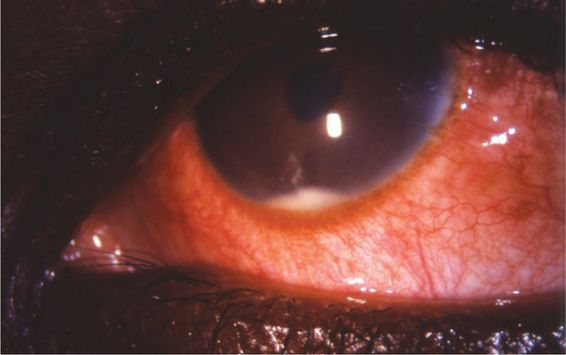

5. Limbal or ciliary flush (Figure 14.2) This is an objective finding, but requires only simple inspection of the eye, without any direct patient contact. The limbus is the border between the cornea and the sclera. It is usually devoid of visible vessels or redness. When a problem causes inflammation of either the cornea (keratitis) or the anterior portion of the uveal tract (iritis), a limbal flush occurs. The flush means that there are visible (dilated) blood vessels concentrated at the border of the cornea and the sclera (limbus), and often the area immediately surrounding the limbus is deep pink or red.

FIGURE 14.2 Anterior uveitis. Marked conjunctival injection and perilimbal hyperemia (“ciliary flush”) are seen in this patient with recurrent iritis. SOURCE: photo contributor: Frank Birinyi, MD: Reproduced with permission from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman RJ. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2010. Fig. 2-27. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

6. Any corneal irregularity (i.e., anything except a perfectly clear cornea)

7. Any history of trauma or obvious evidence of trauma to the eye

8. Cutaneous vesicular distribution on the face or near an eye Cutaneous vesicular distribution on the face or near an eye indicates the potential of either herpes simplex or herpes zoster eye infections. Both can cause permanent visual impairment by damaging the cornea. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is shingles involving ocular structures. This is especially true if the ophthalmic (the most superior) branch of cranial nerve 5 is affected. Hutchinson’s sign, presence of vesicles on the nose can be indicative of ocular involvement.

9. Any soft tissue swelling near the eye (dacryocystitis, orbital cellulitis, preseptal cellulitis) Swelling and inflammation (cellulitis) of one or both eyelids and/or other structures immediately surrounding the eye may indicate a serious bacterial infection. If orbital cellulitis is present there is usually some abnormality of extraocular movement (EOM). Adults may have a history of trauma (including surgery) preceding development of any of the problems.

10. Hyphema/hypopyon Under normal circumstances fluid is not visible in the anterior chamber. A visible meniscus of blood, cloudy fluid or purulent material in the anterior chamber is an ocular emergency. Blood in the anterior chamber due to trauma or over-anticoagulaltion is called a hyphema, while cloudy or purulent fluid is a hypopyon, (Figure 14.3) caused by inflammation or infection of the internal structures of the eye. In addition, most patients will also usually have other cardinal signs, i.e. visual impairment, eyeball pain, photophobia, limbal flush.

FIGURE 14.3 Hypopyon in acute anterior uveitis (iritis). (Reproduced with permission, from Riordan-Eva P, Cunningham ET, eds. Vaughan & Asbury’s General Ophthalmology. 18th ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2011:60. Fig. 3-4. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.)

11. Contact lens wearers Another special situation involves patients who regularly use contact lenses, or whose intermittent use of contact lenses immediately preceded the onset of the acute condition for which they have sought care. Contact lens wearers may have a more serious disorder than is initially suspected due to infections with unusual organisms, keratitis, or corneal abrasion. It is prudent to recommend referral to an eye-care specialist for virtually all patients who have used contact lenses recently and have developed a new eye or vision complaint. This is true even if they seem to have only an irritative, allergic, or viral or bacterial conjunctivitis.

Common Causes of Inflamed, Red Eyes

The three most common causes of red eye are allergic, viral, and bacterial conjunctivitis (Table 14.2). Their relative incidence is in the order as listed. That is, allergic conjunctivitis is the most common, and may affect up to 40% of the US population. The infectious causes of conjunctivitis are, as a group, second to allergic causes. The most common types of infectious conjunctivitis are those caused by viruses. The next most common are those due to bacteria. Irritative conjunctivitis is another common cause of redness in the eye and is due to exposure to wind, dust, or swimming pool chlorine. The other three are usually not completely manageable in the community pharmacy setting. However, meaningful service can be provided by a screening/triage function, and, where appropriate, by recommendation of initial management suggestions in the form of nonpharmacological modes or OTC medications.

| TABLE 14.2 | Red Eye |

Irritative Conjunctivitis

Chlorine from swimming pools, smoke, intense light (snow blindness), dry windy conditions are common causes of conjunctival inflammation, redness, and irritation. Usually bilateral, these conditions are all best treated by avoidance of the irritant and preventive measures (wearing goggles or sunglasses), but topical OTC products may provide temporary relief until preventive measures can be fully implemented. The patients should be queried about specific details of recent exposure to any of the common irritants, use of prescription eye drops, recent changes in eye cosmetics, or contact lens solutions. Patients with new or long-term glaucoma medication, contact lens wearers, and suspected allergic reactions to eye products should be referred to an eye-care specialist.

Allergic Conjunctivitis

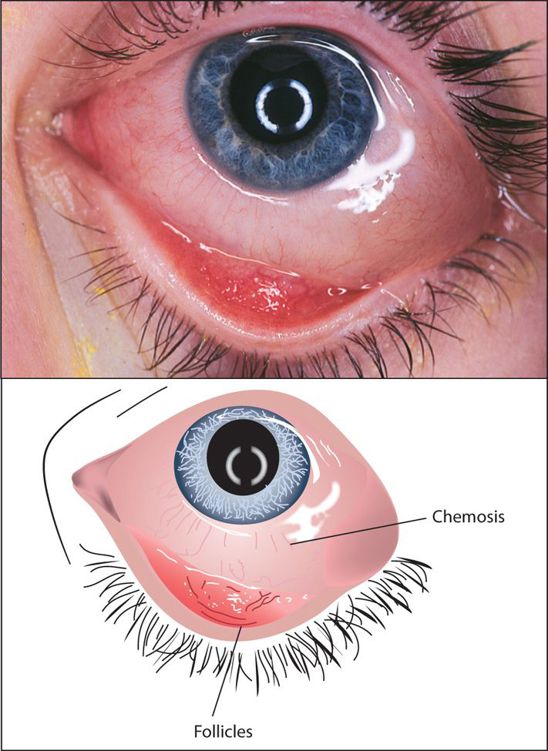

Allergic conjunctivitis characteristically presents as an acute episode of allergy affecting the eyes. Often, however, it becomes either frequently recurring or chronic. There are two basic types: seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC) and perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC). These differ by the types of allergens causing symptoms. SAC is most typically caused by seasonal plant pollens, whereas PAC is usually caused by allergens to which the patient is exposed year-round (most commonly the house dust mite, animal dander, and components of the cockroach). These two basic types of allergic conjunctivitis parallel the system of categorizing the types of allergic rhinitis. In fact, allergic conjunctivitis commonly coexists with allergic rhinitis and less frequently with other atopic diseases (asthma and/or atopic dermatitis). While PAC is sometimes thought of as chronic, most patients present with episodes of acute exacerbations, as opposed to having symptoms constantly. SAC can even be chronic during the patient’s “season,” which may extend for up to 6 months. However, with SAC, there is clearly an extended period of time (months) when the patient is virtually without allergic conjunctivitis symptoms. The most common symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, whether it is SAC or PAC, are itching of the eye, watering of the eye, and redness of the conjunctiva. These manifestations are usually bilateral. The itch can be intense. The wateriness is characterized by predominantly being clear, rarely mucoid, but never purulent. Rarely does the wateriness obstruct vision to any significant degree. The redness is variable, but usually mild to moderate and generalized throughout the visible bulbar and palpebral conjunctivae (Figure 14.4). Sometimes there is a mild foreign body sensation in the eye.

FIGURE 14.4 Allergic conjunctivitis. Conjunctival injection, chemosis, and a follicular response in the inferior palpebral conjunctiva in this patient with allergic conjunctivitis secondary to cat fur. SOURCE: photo contributor: Timothy D. McGuirk, DO. Reproduced with permission from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman, RJ. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2010. Fig. 2-8. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

There are three subtypes of allergic conjunctivitis that warrant special mention. All three may involve the cornea (cause keratitis), and progression could cause serious, possibly vision-threatening damage to the cornea. These three conditions are vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), and giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC). Therefore, patients suspected of having any one of these three should be referred to an eye-care specialist. They are best recognized by their severity and chronicity compared to simple SAC or PAC and additional symptoms of keratitis or photophobia. All three have in common with SAC and PAC, the symptom of itch. However, VKC, in particular, may cause very intense itching. They are distinct from SAC and PAC in that they are chronic and are often associated with a stringiness to the ocular discharge. Photophobia, while common in VKC is less common in AKC and GPC. VKC is common in male children with other atopic diseases and begins from ages 4 to 10 years and disappears after puberty. AKC occurs most often in young adult males and continues into the fifth decade. The presence of atopic dermatitis on the eyelids and face is very common. GPC occurs predominately in contact lens users, but can occur following surgery as a reaction to sutures. If anything suggests these more serious forms, or the patient does not respond to continued use of an OTC product or nonpharmacological mode of management that has been suggested, the patient should be referred.

Viral Conjunctivitis

Viral conjunctivitis is, by far, the most common of the infectious causes of conjunctivitis (up to 80%). While there is considerable overlap in the manifestations of viral and allergic conjunctivitis, there are some differences. Viral conjunctivitis usually begins on one side, but may spread to the other eye, whereas allergic conjunctivitis is almost always bilateral (unless a load of antigen is deposited into one eye, perhaps, by rubbing the eye after touching an allergen). The discharge in viral conjunctivitis varies considerably ranging from a thin, clear, watery discharge to a mucoid and/or mucopurulent discharge, overlapping in appearance with the discharges of both allergic conjunctivitis and bacterial conjunctivitis (Figure 14.5). Viral conjunctivitis may be associated with other symptoms of upper respiratory viral infectious disease, such as rhinitis, scratchy or mildly sore throat, mild malaise, possibly a low-grade fever, and possibly cough. If itch is associated with viral conjunctivitis, it is much less marked than that associated with allergic conjunctivitis. The degree of redness varies and is not a useful differential feature. One of the most unique features of viral conjunctivitis is that it may be associated with lymphadenopathy, particularly in the periauricular area. Positive findings favor viral conjunctivitis, but their absence does not rule out other possibilities. Follicles, especially on the palpebral conjunctivae, may occur with either viral or allergic conjunctivitis, although most sources indicate that they are more common with allergic disease. Their presence can be determined with minimal patient contact, by slight downward traction on the lower lid, so as to expose the palpebral conjunctiva.

FIGURE 14.5 Viral conjunctivitis. Note the characteristic asymmetric conjunctival injection. Symptoms first developed in the left eye, with symptoms spreading to the other eye a few days later. A thin watery discharge is also seen. SOURCE: photo contributor: Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS. Reproduced with permission from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman, RJ. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2010. Fig 2–4. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

The majority of viral conjunctivitis is caused by one of the adenoviruses. There is no pharmacologic therapy that is effective for this entity. This is unfortunate, as the infection is highly communicable. The incubation period ranges from 5 to 12 days and the period of communicability ranges from 10 to 12 days, continuing while the eye is red and symptomatic. Patients, especially children, with adenoviral conjunctivitis remain infectious during the symptomatic phase of the disease, regardless of whether or not they are being treated with an ocular anti-infective. Because of the difficulty of easily distinguishing between viral and bacterial conjunctivitis most patients with pink eye are started on a broad spectrum anti-bacterial agent and told that they will no longer be infectious after 24 to 48 hours of use of that anti-bacterial agent. However, if in fact the patient has a viral conjunctivitis, they will remain infectious, despite anti-bacterial therapy. It is an unfortunate fact that many school policies allow a child to return to school after having been on an anti-bacterial agent for 24 to 48 hours, despite the fact that most of them have a viral conjunctivitis for which the anti-bacterial has absolutely no effect. This certainly contributes to the frequency of viral conjunctivitis among children in such school systems.

While the pharmacist cannot recommend any curative therapy, some advice for symptomatic treatment can be suggested. In fact, except for the two specific types of viral conjunctivitis discussed below, there is no effective anti-viral therapy available. However, some patients will derive some symptomatic relief from cold compresses, topical wetting agents (artificial tears), possibly the topical OTC antihistamine/mast cell stabilizer (ketotifen), and even topical decongestants. As usual, the pharmacist is wise to advise the patient to seek medical care for symptoms that worsen at any time, or for symptoms that do not improve in 3 to 4 days.

Two specific types of viral conjunctivitis deserve separate mention. These are viral conjunctivitis due to herpes simplex virus or herpes zoster virus. Fortunately, these two viruses comprise a small minority of the various viral causes of conjunctivitis. Cutaneous vesicles on the face or near an eye are a common manifestation of viral infectious disease due to herpes simplex and herpes zoster. Initially, symptoms of herpes simplex conjunctivitis may be limited to irritation or pain in the eye, watery discharge, and visual blurring. Herpes simplex virus can cause a progressive, serious, and potentially sight-threatening type of viral conjunctivitis. It usually includes involvement of the cornea, making it a viral keratoconjunctivitis or pure viral keratitis (Figure 14.1). Symptoms often include significant irritation (severe foreign body sensation), photophobia, in addition to redness, watery discharge, and visual blurring. In some cases, vesicles occur on the skin of the eyelids or around the eye. If vesicles are present on or near the eyes in a patient with other manifestations of a red eye, especially if there is any corneal abnormality, a limbal flush or any of the four findings that indicate referral (eye pain, visual impairment, photophobia, or severe foreign body sensation), suspect herpes simplex keratitis and refer the patient to an ophthalmologist immediately. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is the other potentially sight-threatening cause of viral conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis. HZO is a type of shingles. The prodrome of stinging, burning, and sometimes itching occurs before the development of any visible lesions. The initial lesion is a vesicle, which progresses through the stages of pustule, ulcer, and crust. Both the signs and symptoms of HZO occur in the pattern of a dermatome. When the trigeminal (fifth cranial) nerve is affected, facial lesions will occur. When the most superior (ophthalmic) branch of the trigeminal nerve is affected, ocular involvement is likely. Some sources mention Hutchinson’s sign, which is the presence of a vesicle on or near the tip of the nose. Supposedly, this increases the chance of corneal involvement. Any suggestion of HZO, by symptoms (including eye pain, visual disturbance, photophobia, severe foreign body sensation) or a dermatomal distribution of lesions on the face or near the eye or nose, should warrant immediate referral to an ophthalmologist.

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Bacterial conjunctivitis is the least common of the three conditions that are the emphasis of this chapter (Figure 14.6). It may also be the easiest to differentiate from the other two common types of conjunctivitis (allergic and viral). The most useful differential feature is the nature of the ocular discharge. Some sources indicate that bacterial conjunctivitis commonly causes matting of the eyelids, especially upon awakening in the morning. While it is true that if this feature is present, it suggests bacterial conjunctivitis, if it is not present, the entity cannot be ruled out. Depending on the way the patient may express their symptoms, some cases of allergic and many cases of viral conjunctivitis may also be associated with a degree of eyelid matting. Another commonly cited differential feature is that the discharge is usually purulent, at least more often so than allergic or viral conjunctivitis. Again, while this is useful if found, a lack of purulence cannot be relied on to rule out bacterial conjunctivitis. Similar to viral conjunctivitis, bacterial conjunctivitis most often begins in only one eye. However, it usually becomes bilateral, probably because of autoinoculation. In fact, bilateral involvement with bacterial conjunctivitis is more likely to occur than with viral causes. A useful differential feature is the relative lack of associated symptoms with bacterial conjunctivitis. It is not associated with other manifestations of upper respiratory infection. Manifestations are usually limited to the eye(s). Another possible differential feature is the lack of ocular itching, which usually occurs in allergic and sometimes in viral conjunctivitis. Due to the purulent nature of the discharge, bacterial conjunctivitis is more likely than allergic or viral causes to create some visual blurring. However, this blurring should clear completely with removal or cleansing of the discharge from the eye. There should be no permanent visual disturbance from bacterial conjunctivitis. If visual abnormalities persist after cleaning the discharge from the eye, some complication, such as a keratitis, should be suspected and the patient immediately referred. In children, the most common etiologic bacteria are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis, although Staphylococcus sp may be involved. In adults, S. aureus is most common, followed by S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and possibly coagulase negative Staphylococcus sp. Any specific therapy for what is truly a bacterial conjunctivitis will require a primary care provider’s prescription. That is, all patients suspected of having a true bacterial conjunctivitis should be referred to a primary care provider. The urgency of referral might depend most on duration and severity of symptoms. Most cases of bacterial conjunctivitis are not sight threatening, and as such not an urgency. However, significant discomfort can arise from the symptoms, and it is best to have the patient seen as soon as possible. The best thing a pharmacist could suggest other than referral would be warm compresses for the discomfort.

FIGURE 14.6 Bacterial conjunctivitis. Mucopurulent discharge, conjunctival injection, and lid swelling in a 10-year-old with H. influenzae conjunctivitis. SOURCE: photo contributor: Frank Birinyi, MD. Reproduced with permission from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman, RJ. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2010. Fig. 2-2. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

Two special types of bacterial conjunctivitis deserve brief mention. Both of these two special types of bacterial conjunctivitis can occur in newborns, although these patients would be unlikely to be initially presented to a pharmacist. Both are most often unilateral, but may become bilateral due to autoinoculation. Both would require immediate referral. The first is hyperpurulent or hyperacute conjunctivitis and the second is inclusion conjunctivitis. In adults, both are usually sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs). Hyperpurulent or hyperacute conjunctivitis is usually due to N. gonorrhoeae. The hyperpurulent term simply means that the discharge is unmistakably purulent, copious, and continuous. Almost as soon as the discharge is cleared, it reaccumulates. Other symptoms are similar to the more common types of bacterial conjunctivitis, albeit perhaps more severe. In addition, eyelid swelling, conjunctival edema (chemosis), and periauricular lymphadenopathy may occur. Untreated, this process can quickly progress to cause corneal ulceration and perforation. Any indication of photophobia or severe foreign body sensation may be an indication that this corneal involvement has already begun. In all cases, immediate referral is indicated, usually for systemic therapy of gonorrhea. The patient should be advised that sexual contacts are at risk of some type of gonococcal infection. Inclusion conjunctivitis is due to certain serotypes of Chlamydophila trachomatis. The presentation is much less dramatic than hyperpurulent conjunctivitis. In fact, inclusion conjunctivitis appears more like viral conjunctivitis. The redness may be somewhat more pronounced than typical viral conjunctivitis, and there may be follicles on the palpebral conjunctiva. The discharge is mucoid and usually not profuse, but can progress to have a more purulent nature. Itch is not a common feature. However, there may be a rather significant degree of foreign body sensation. If this disease is even suspected, immediate referral should be advised. This is necessary for both appropriate systemic anti-microbial therapy and contact follow-up (as it is also usually an STI in adults).

Miscellaneous Eye Conditions

The following conditions are not commonly sight or vision threatening, and rarely in need of emergent care. However, there is little that the pharmacist can suggest, other than appropriate (nonurgent, nonemergent) referral to a primary care or eye-care provider and possibly initial symptomatic (nonpharmacologic or OTC) care. Some of these conditions can accompany or coexist with one of the three more common causes of conjunctivitis (allergic, viral, bacterial). However, some are entirely separate entities, and will often be recognizable as such. They will only be briefly defined and characterized. The interested reader is referred to other sources for more detail.

Blepharitis is inflammation of the eyelids, usually manifest as redness and swelling of the margins (outer edges) of the eyelids. It may be allergic or bacterial in etiology. It may occur along with allergic conjunctivitis.

Chalazion is chronic inflammation due to plugging of a meibomian gland in an eyelid. It is a benign process, which is often asymptomatic, except for the patient noticing a lump on the eyelid.

Hordeolum (or stye) is an acute inflammation due to plugging of one of several different glands in the eyelid. Many become acutely infected usually with bacteria from the skin.

Pingueculum is a degenerative process of the conjunctiva. It is relatively common, benign, usually asymptomatic, and consists of a white or yellowish deposit of hyaline on the bulbar conjunctiva, at the 3- and/or 9-o’clock positions relative to the cornea. Commonly occurs in patients exposed to dry windy conditions.

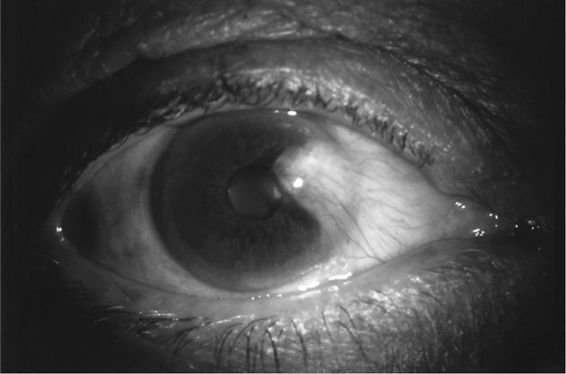

Pterygium is similar to a pingueculum in appearance but can grow over the cornea, and has different pathological origins. It may partially obstruct vision. (Figure 14.7)

FIGURE 14.7 Pterygium encroaching on the cornea and invading the visual axis. SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Riordan-Eva P, Cunningham ET, eds. Vaughan & Asbury’s General Ophthalmology, 18th ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2011:106. Fig. 5-32. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education LLC.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is due to a broken or leaking vessel in the conjunctiva, which results in deposition of a contiguous area of blood under the conjunctival membrane. It is asymptomatic. Most commonly, it is caused by rubbing the eye, especially in response to itching. However, it may be due to a sudden sneeze or cough. Patients usually become aware of the process by seeing their eye in a mirror, or by having somebody else point it out to them. It is a self-limiting, completely benign process that resolves in several days.

Entropion and ectropion are abnormal inward and outward (respectively) folding or turning of the (usually lower) eyelid. Entropion can result in corneal irritation and even abrasion. Ectropion is less symptomatic, but may be associated with increased tearing, due to decreased tear retention, along with resultant dry eyes. Long-term use of irritative ophthalmic solution for glaucoma can cause ectropion.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Cronau H, Kankanala RR, Mauger T. Diagnosis and management of red eye in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:137-144.

2. Sethuraman U, Kamat D. The red eye: evaluation and management. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48:588-600.

3. Seth D, Kahn FI. Causes and management of red eye in pediatric ophthalmology. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:212-219.

4. Deibel JP, Cowling K. Ocular inflammation and infection. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2013;31:387-397.

5. Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis—a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013;310:1721-1729.

6. Visscher KL, Hutnick CML, Thomas M. Evidence-based treatment of acute infective conjunctivitis—breaking the cycle of antibiotic prescribing. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:1071-1075.

7. Leonardi A, Bogacka E, Fauquert JL, et al. Ocular allergy: recognizing and diagnosing hypersensitivity disorders of the ocular surface. Allergy. 2012;67:1327-1337.

8. Kari O, Saari KM. Diagnostics and new developments in the treatment of ocular allergies. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012;12:232-239.

9. American Academy of Opthalmology Corneal/External Disease Panel. Preferred Practice Guidelines. Conjunctivitis. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2013. www.aao.org/ppp. Accessed 2014, June 15.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree