Overview

In many discussions of patient safety, it is assumed that the workforce is up to the task—in training, competency, and numbers. In these formulations, a combination of the right processes, information technology, and culture is enough to ensure safe care.

However, as any frontline worker can tell you, neglecting issues of workforce sufficiency and competency omits an important part of the equation. For example, a nursing or physician staff that is overworked and demoralized will breed unsafe conditions, even if good communication, sound policies, and efficient computers are in place.

In this chapter, I will discuss some key issues in workforce composition and organizational structure, including the nursing workforce, Rapid Response Teams, and trainee-related matters such as duty-hour restrictions and the so-called “July effect.” I’ll close with a discussion of the “second victim” phenomenon: the toll that errors take on caregivers themselves. In the next chapter, I’ll discuss issues of training and competency.

Nursing Workforce Issues

Much of our understanding of the interaction between workforce and patient outcomes and safety comes from studies of nursing. The combination of pioneering research exploring these associations,1–5 a U.S. nursing shortage that emerged in the late 1990s, and effective advocacy by nursing organizations (because most hospital nurses in the United States are salaried and employed by the hospitals, they have a strong incentive to advocate for sensible workloads; contrast this to physicians, most of whom are self-employed and therefore calibrate their own workload) has created this focus.

Substantial data suggest that medical errors increase with higher ratios of patients to nurses. One study found that surgical patients had a 31% greater chance of dying in hospitals when, on average, a nurse cared for more than seven patients. For every additional patient added to a nurse’s average workload, patient mortality rose 7%, and nursing burnout and dissatisfaction increased 23% and 15%, respectively. The authors estimated that 20,000 annual deaths in the United States could be attributed to inadequate nurse- to-patient ratios.1 A recent study, the most methodologically rigorous to date, confirmed the association between low nurse staffing and increased mortality, further demonstrating that high rates of patient turnover were also associated with mortality even when average staffing was adequate.5

Unfortunately, these studies point to a demand for nurses that cannot be met by the existing supply. Despite some easing of the U.S. nursing shortage, in 2012 the demand for nurses continued to exceed supply by over 100,000; this mismatch was projected to grow (to a shortfall of more than 250,000 registered nurses) with the aging of the American population.6 While more young people have entered the nursing profession in recent years, nearly one million of the nation’s nurses (nearly one in four) are over age 50, adding to the challenge.

Efforts to address the nursing shortage have centered on improved pay, benefits, and working conditions. In the future, technology could play an important role as well, particularly if it relieves nurses of some of their paperwork burden and allows them to spend more time with patients. In Chapter 13, I described the lunacy that results when a nurse takes a digital blood pressure reading and then begins an error-prone struggle to transcribe it in multiple places. Situations like this, which go on dozens of times during a typical shift, are one reason many nurses believe so much of their time and training are wasted.

Importantly, even as the nursing shortage has catalyzed efforts to improve pay, hours, staffing, and technology, it has also brought long-overdue attention to issues of nursing culture and satisfaction. Studies in this area often point to problematic relationships with physician colleagues. In one survey of more than 700 nurses, 96% said they had witnessed or experienced disruptive behavior by physicians. Nearly half pointed to “fear of retribution” as the primary reason that such acts were not reported to superiors. Thirty percent of the nurses also said they knew at least one nurse who had resigned as a result of boorish—or worse—physician behavior, while many others knew nurses who had changed shifts or clinical units to avoid interacting with particular doctors.7–9 These concerns have been an important driver for the interdisciplinary training discussed in Chapter 15, and for increasing efforts to enforce acceptable behavioral standards among all healthcare professionals (Chapter 19).10,11

Driven by the strong association between nurse staffing and outcomes, 15 states (including California, Texas, and Illinois) have legislated minimum nurse-to-patient ratios (usually 1:5 on medical-surgical wards and 1:2 in intensive care units), and 16 states restrict mandatory overtime. The jury is still out on whether these legislative solutions are enhancing safety. Some nurses complain that ancillary personnel (clerks, lifting teams) have been released in order to hire enough nurses to meet the ratios, resulting in little additional time for nurses to perform nursing-related tasks. Commentators have pointed out that the determination of adequate nurse staffing is complex and fluid, since it needs to take into account patient acuity, availability of adequate support staff, and a host of other factors that may vary shift-by-shift.12,13

In addition to these staffing standards, there has been an effort to develop quality and safety measures linked to the adequacy of nursing care. These “nursing-sensitive” measures include rates of falls, urinary tract infections, and decubitus ulcers.14,15 While the Joint Commission assesses nurse staffing and working conditions in its accreditation process, many hospitals aspire to the even higher standards of the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s “magnet status.” Limited research suggests an association between magnet status and patient outcomes.16

Rapid Response Teams

Analyses of deaths and unexpected cardiopulmonary arrests in hospitals often find signs of patient deterioration that went unnoticed for hours preceding the tragic turn of events. Measures of these so-called “failure to rescue” cases are included among the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators (Appendix V).17–19 Identifying warning signs may require better monitoring systems or improved nurse staffing.

But such cases may also reflect a cultural problem: analyses of failure to rescue cases sometimes reveal that a nurse noticed that something was awry but was either unable to find an appropriate responder or reluctant to bypass the traditional hierarchy (i.e., the standard procedure to call the private physician at home before the in-house ICU physician, or the intern before the attending). Table 16-1 lists a variety of causes of failure to rescue.19

| Monitoring technology is used only in the intensive care unit or step-down units |

| Hospital-ward monitoring is only intermittent (vital sign measurements) |

| Intervals between measurements can easily be eight hours or longer |

| Regular visits by a hospital-ward nurse vary in frequency and duration |

| Visits by a unit doctor may occur only once a day |

| When vital signs are measured, they are sometimes incomplete |

| When vital signs are abnormal, there may be no specific criteria for activating a higher-level intervention |

| Individual judgment is applied to a crucial decision |

| Individual judgment varies in accuracy according to training, experience, professional attitude, working environment, hierarchical position, and previous responses to alerts |

| If an alert is issued, the activation process goes through a long chain of command (e.g., nurse to charge nurse, charge nurse to intern, intern to resident, resident to fellow, fellow to attending physician) |

| Each step in the chain is associated with individual judgment and delays |

| In surgical wards, doctors are sometimes physically unavailable because they are performing operations |

| Modern hospitals provide care for patients with complex disorders and coexisting conditions, and unexpected clinical deterioration may occur while nurses and doctors are busy with other tasks |

The concept of Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) was developed to address these problems. Now sometimes called “Rapid Response Systems” (RRSs) to emphasize the importance of both the monitoring and response phases, such teams have been widely promoted over the past decade, most notably when they were included among the six “planks” of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “100,000 Lives Campaign” in 2005 (Table 20-2).20,21

Despite the face validity of RSSs, the evidence supporting them remains limited. While several single-center, before-and-after comparisons found a reduction in hospital cardiac arrests,19,22–24 a large randomized multisite study demonstrated no impact.25 Two meta-analyses have also questioned the benefit of RRSs.26,27

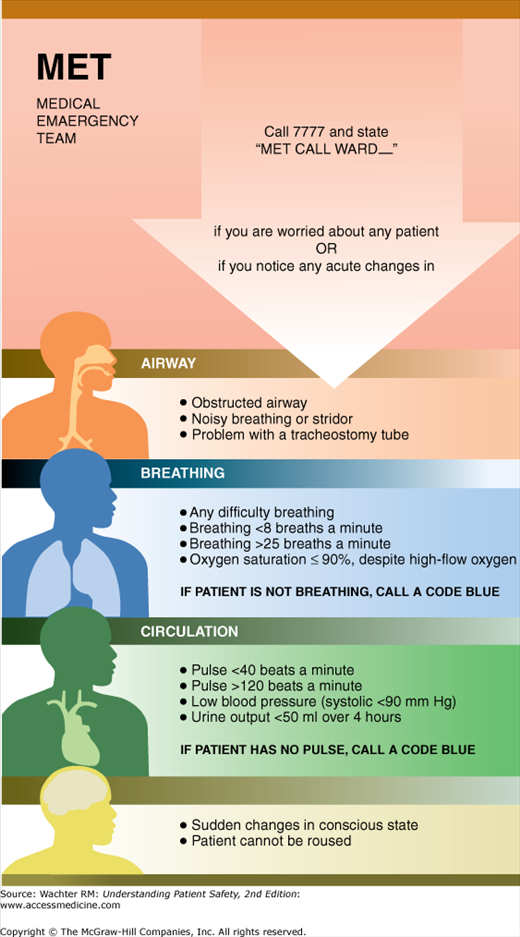

At the present time, the optimal criteria to trigger an RRT response are unknown.19 Some institutions use strict objective criteria, while others emphasize that anyone with concerns should feel free to activate the RRT. Some hospitals even allow patients and families to call the team. One Australian hospital’s poster illustrating its vital sign criteria for activating its Medical Emergency Team (another name for RRT) is shown in Figure 16-1.19

Similarly, the optimal composition of the responding team remains uncertain. Some hospitals have used physician-led teams, while other RRTs are led by nurses, often with respiratory therapists as partners.19 RRTs have a positive impact on nursing satisfaction and perhaps retention, although the magnitude of this benefit has not been fully quanified.28

While the Joint Commission does not specifically require the presence of an RRT, it does mandate that accredited organizations select “a suitable method that enables health care staff members to directly request additional assistance from a specially trained individual(s) when the patient’s condition appears to be worsening.”29 Ongoing research will hopefully answer the many questions surrounding RRTs, including the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. An RRT with round-the-clock dedicated staffing can easily cost a hospital hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

For now, RRTs remain attractive in theory, and their underlying rationale—that hospitals should have robust systems to monitor patients for deterioration as well as a structure and culture that ensure that appropriately qualified staff and necessary technology are available to care for deteriorating patients—seems unassailable. That said, the absence of hard evidence of benefit is a concern, and RRTs have become Exhibit A in the debate among patient safety experts regarding the level of scientific evidence required before a so-called “safe practice” is promoted or required (Chapter 22).30–32

House Staff Duty Hours

Amazingly, there is virtually no research linking safety or patient outcomes to the workload of practicing (i.e., nontrainee) physicians. Dr. Michael DeBakey, the legendary Texas heart surgeon, was once said to have performed 18 cardiac bypass operations in a single day! The outcomes of the patients (particularly patient number 18) have not been reported. But the implicit message of such celebrated feats of endurance is that “real doctors” do not complain about their workload; they simply soldier on. With little research to question this attitude and with the dominant payment system in the United States continuing to reward productivity over safety, there have been few counterarguments to this machismo logic.

The one area in which this has changed is in the workload of physician trainees, particularly residents. At the core of residency training is the ritual of being “on call”—staying in the hospital overnight to care for sick patients. Bad as things are now, they have markedly improved since the mid-1900s, when many residents actually lived at the hospital (giving us the term “house officer”) for months at a time. Even as recently as 20 years ago, some residents were on call every other night, accumulating as many as 120 weekly work hours—which is particularly remarkable when one considers that there are only 168 hours in a week.

Although resident call schedules became more reasonable over the past generation, until recently many residents continued to be on call every third night, with workweeks of more than 100 hours. But change has not come easily. As efforts to limit house staff shifts gained momentum, some physician leaders argued that traditional schedules were necessary to mint competent, committed physicians. For example, in 2002 the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine wrote that long hours:

… have come with a cost, but they have allowed trainees to learn how the disease process modifies patients’ lives and how they cope with illness. Long hours have also taught a central professional lesson about personal responsibility to one’s patients, above and beyond work schedules and personal plans. Whether this method arose by design or was the fortuitous byproduct of an arduous training program designed primarily for economic reasons is not the point. Limits on hours on call will disrupt one of the ways we’ve taught young physicians these critical values … We risk exchanging our sleep-deprived healers for a cadre of wide-awake technicians.33

Therein lies the tension: legitimate concerns that medical professionalism might be degraded by “shift work” and that excellence requires lots of practice and the ability to follow many patients from clinical presentation through work-up to denouement, balanced against worries regarding the effects of fatigue on performance and morale.34–37 The latter concerns are well grounded. One study showed that 24 hours of sustained wakefulness results in performance equivalent to that of a person with a blood alcohol level of 0.1%—above the legal limit for driving in every state in the United States.38

Although early researchers felt that this kind of impairment occurred only after very long shifts, we now know that chronic sleep deprivation is just as harmful. Healthy volunteers performing math calculations were just as impaired after sleeping 5 hours per night for a week as they were after a single 24-hour wakefulness marathon.39 The investigators in this study didn’t check to see what happened when both these disruptions occurred in the same week, the norm for many residents operating under traditional training models.

Although it defies common sense to believe that sleep-deprived brains and bad medical decisions are not related, hard proof of this intuitive link has been surprisingly hard to come by. Most studies using surgical simulators or videotapes of surgeons during procedures show that sleep-deprived residents have problems with both precision and efficiency, yet studies of nonsurgical trainees are less conclusive. One showed that interns who averaged less than 2 hours of sleep in the previous 32 hours made nearly twice as many errors reading ECGs and had to give each tracing more attention, especially when reading several in a row.40 Another found that medical interns performed better on a simulated clinical scenario after a 16-hour shift than after a traditional extended duration shift.41 Yet other studies showed that tired radiology residents made no more mistakes reading x-rays than well-rested ones, and sleepy ER residents performed physical examinations and recorded patient histories with equal reliability in both tired and rested conditions.42

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME, the group that blesses the 7800 residency programs in the United States, involving over 100,000 trainees) stepped into the breach, limiting residents to a maximum of 80 hours per week, with no shift lasting longer than 30 consecutive hours and at least one day off per week (Table 16-2).43 Studies that followed these changes yielded surprisingly mixed results, with the weight of the evidence showing no significant change in patient safety or overall outcomes, but improved quality of life for residents.43–47

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree