Venous Access: External and Internal Jugular Veins

The external and internal jugular veins are frequently used for access to the central venous circulation. In this chapter, external jugular venous cutdown, internal jugular venous cutdown, and percutaneous internal jugular venous cannulation are presented. Because the most common method is percutaneous internal jugular venous cannulation, several approaches (posterior, anterior, and ultrasound-guided) are discussed.

This chapter also discusses placement of two types of implantable venous access devices: Ports and tunneled venous catheters.

Special considerations referable to placement of large-diameter venous access devices for hemodialysis are discussed in Chapter 38.

The anatomy of the carotid sheath is introduced. The carotid artery and the anatomy of the carotid region are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 9.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified central venous line placement, ultrasound use for intravascular access, insertion of implantable venous access devices, and pulmonary artery catheter placement as “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedures.

Pulmonary artery catheter placement is not explicitly described in this text; critical care references at the end explain this procedure, which begins with the access procedures described in this chapter and in Chapter 14.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE—EXTERNAL JUGULAR VEIN CUTDOWN

Position patient with head turned to one side, slight Trendelenburg positioning

Identify external jugular vein

Small transverse incision in midneck

Identify vein and dissect proximally and distally

Tunnel catheter

Ligate vein cephalad and cannulate vein, directing it centrally

Confirm central location

Tie vein around catheter

Close skin incision and secure catheter

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Carotid artery puncture

Pneumothorax

Failure of catheter to pass centrally

LIST OF STRUCTURES

External jugular vein

Internal jugular vein

Common facial vein

Common carotid artery

Platysma muscle

Sternocleidomastoid muscle

External Jugular Venous Cutdown

The external jugular vein, because of its superficial location, is an easy site for venous cutdown or percutaneous cannulation. Difficulty is often encountered in passing a catheter centrally from this location. In addition, the vein is often thrombosed in patients in whom the procedure has been attempted before. For these reasons, the more difficult internal jugular approaches may be preferred.

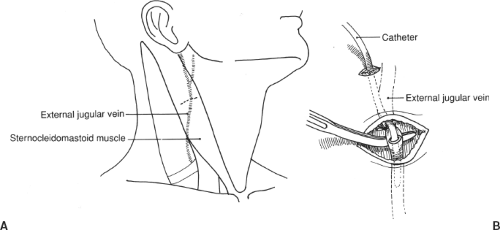

Venous Anatomy of the Neck and External Jugular Venous Cutdown (Fig. 8.1)

Technical Points

Position the patient with the head turned to one side. A slight Trendelenburg position will increase venous pressure in the neck, facilitating identification of the vein and decreasing the chance of venous air embolism. Apply pressure to the platysma muscle just above the clavicle and identify the external jugular

vein as it distends with blood. Infiltrate the area overlying the vein with local anesthetic and make a small transverse skin incision over the vein in the midneck. Make the incision with care to avoid injury to the vein, which lies very superficially. Identify the vein and dissect parallel to the vein proximally and distally for a length of about 1 cm. Elevate the vein into the wound with a hemostat. Ligate the vein proximally (cephalad) and place a ligature around the distal vein.

vein as it distends with blood. Infiltrate the area overlying the vein with local anesthetic and make a small transverse skin incision over the vein in the midneck. Make the incision with care to avoid injury to the vein, which lies very superficially. Identify the vein and dissect parallel to the vein proximally and distally for a length of about 1 cm. Elevate the vein into the wound with a hemostat. Ligate the vein proximally (cephalad) and place a ligature around the distal vein.

Figure 8.1 Venous anatomy of the neck and external jugular venous cutdown. A: Venous anatomy of the neck. B: External jugular venous cutdown. |

The catheter should enter the skin at a separate site, rather than through the cutdown incision. Make a small incision about 2 cm above the skin incision and tunnel the catheter under the skin to the incision. A Broviac- or Hickman-type catheter is tunneled under the skin of the chest wall to an exit site located at a flat, stable location (see subsequent sections of this chapter). Generally, the parasternal region, about 10 cm below the clavicle, is selected as the exit site.

Use a number 11 blade for performing a small anterior venotomy, then introduce the catheter. Because of angulation at the juncture of the external jugular vein and the subclavian vein, there may be a tendency for the catheter to “hang up” or to pass out toward the arm rather than centrally. If this occurs, turn the patient’s head back toward the side of cannulation and reattempt to pass the catheter centrally. If necessary, use a floppy-tipped guidewire, under fluoroscopic control, to guide the catheter into the superior vena cava. Tie the catheter in place distally.

Secure the catheter in position and close the incision with interrupted absorbable sutures. If the external jugular vein cannot be cannulated or the central venous circulation cannot be accessed using this approach, extend the incision medially and proceed to the internal jugular vein (Fig. 8.2).

Anatomic Points

The external jugular vein begins in the vicinity of the angle of the mandible, within or just inferior to the parotid gland. It runs just deep to the platysma muscle. Its course is approximated by a line connecting the mandibular angle and the middle of the clavicle. It crosses the sternocleidomastoid muscle and pierces the superficial lamina of the deep cervical fascia roofing the omoclavicular triangle. It continues its vertical course to end in either the subclavian or, about one-third of the time, the internal jugular vein. When it pierces the superficial lamina, its wall adheres to the fascia. This tends to hold a laceration of the vein open and predisposes the patient to air entrance if the vein is severed at this site. The vein can be occluded by pressure just superior to the middle of the clavicle, a point slightly posterior to the clavicular origin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The diameter of the external jugular vein is quite variable and appears to have an inverse relation to the diameter of the internal jugular veins. The right external jugular vein is typically larger in diameter than the

left, partly because it is more closely aligned with the superior vena cava and thus the right atrium.

left, partly because it is more closely aligned with the superior vena cava and thus the right atrium.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE—INTERNAL JUGULAR CUTDOWN

Choose right side if possible, turn head to left, slight Trendelenburg position

Transverse incision centered over division of sternocleidomastoid

Deepen incision through platysma and spread two heads of sternocleidomastoid

Identify internal jugular vein

Dissect in anterior adventitial plane to free several centimeters of vein

Place purse-string suture

Tunnel catheter

Cannulate vein

Tie purse-string suture around vein

Confirm position of catheter

Close incision

At midneck, the external jugular vein is covered only by the platysma muscle and minor branches of the transverse cervical nerve. This branch of the cervical plexus, carrying sensory fibers of C2 and C3, pierces the superficial lamina of the cervical fascia at the posterior edge of the middle of the sternocleidomastoid, then crosses the sternocleidomastoid muscle, passing deep to the external jugular vein to innervate the skin of the anterior triangle of the neck.

Internal Jugular Venous Cutdown

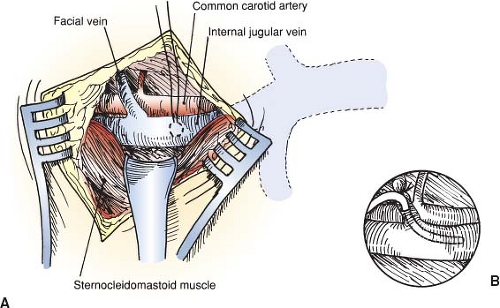

Dissection to the Internal Jugular Vein (Fig. 8.2)

Technical Points

Choose the right internal jugular vein whenever possible. Position the patient supine with the head turned to the contralateral side. The table should be flat or in a slight Trendelenburg position to distend the veins of the neck and minimize the chances of venous air embolism. Infiltrate the skin of a planned transverse skin incision about 2 cm above the clavicle. Make an incision about 3 cm in length, centered over the triangle formed by the division of the sternocleidomastoid muscle into its medial and lateral heads.

Deepen the incision through the platysma until the sternocleidomastoid muscle is encountered, then spread the tissue between the two heads of the muscle to expose the underlying internal jugular vein.

If approaching the internal jugular vein after a failed external jugular vein cutdown, the incision may be high enough to access the common facial vein as it empties into the internal jugular vein. Extend the incision medially across the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Retract the sternocleidomastoid muscle and identify the internal jugular vein just deep to the muscle and lying within the carotid sheath. Search along the anterior and upper aspect of the vein for a large common facial vein. If this can be identified, it can often be cannulated and ligated. This is a simpler way to access the internal jugular vein than is the purse-string suture method (Fig. 8.3).

Anatomic Points

The right internal jugular vein takes a relatively straight course to the central venous circulation, unlike the left, which first enters the brachiocephalic vein. For this reason, it is the preferred site of cannulation.

The minor supraclavicular fossa is the triangle bounded by the clavicle and the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. This fossa is covered by skin, superficial fascia (in which there may be branches of the medial supraclavicular nerve), fibers of the platysma muscle, and the superficial lamina of the cervical fascia.

The internal jugular vein is the dominant structure within the fossa itself. Its exposure may be somewhat tedious owing to the presence of deep cervical lymph nodes. It is located in its own compartment in the carotid sheath and tends to diverge anteriorly from the common carotid artery. This facilitates circumferential dissection of the vein. Because the vein is completely surrounded by the connective tissue elements of the carotid sheath, it does not collapse completely. This can lead to air embolus. Remember that the common carotid artery is posterior to the internal jugular vein at this level and that the apex of the lung is posterior to the common carotid artery. Slightly more inferior, the termination of the internal jugular vein and the beginning of the brachiocephalic vein are in contact with the parietal pleura and the apex of the lung.

Figure 8.2 Dissection to the internal jugular vein. A: Location of purse-string suture on internal jugular vein. B: Alternative placement into facial vein. |

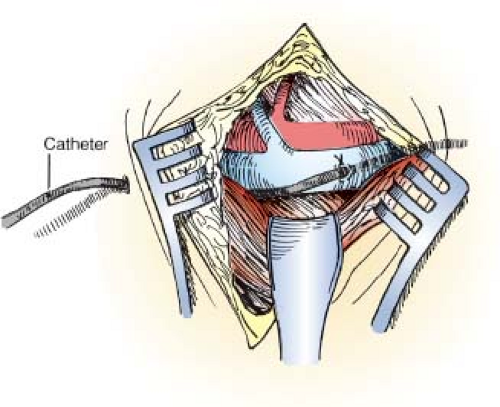

Placement of Purse-String Suture and Cannulation of the Internal Jugular Vein (Fig. 8.3)

Technical and Anatomic Points

Carefully dissect the anterior adventitial plane of the vein to free several centimeters of vein proximally and distally. Pass a right-angle clamp under the vein and place silastic loops proximal and distal to the vein. Lift up on the vein gently with DeBakey pickups, if necessary, to facilitate passage of the right-angle clamp. The internal jugular vein can be ligated if necessary. If injury to the vein occurs, ligation and division of the vein is the safest course.

Place a 4-0 Prolene purse-string suture on the anterior surface of the vein. Place this suture in four bites, drawing a small square on the vein. Make a small incision, using a number 11 blade, in the center of the purse-string and insert the catheter. Confirm passage into the central circulation and good position of the catheter tip. Tie the purse-string suture and close the incision in layers with interrupted absorbable suture.

Percutaneous Cannulation of the Internal Jugular Vein by Posterior Approach

Posterior Approach to the Internal Jugular Vein by Anatomic Landmarks (Fig. 8.4)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine, in a moderate Trendelenburg position, with the head turned to the contralateral side. Palpate the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle about two fingerbreadths above the clavicle (Fig. 8.4A). Use the thumb of the nondominant hand to stabilize and elevate the sternocleidomastoid muscle by hooking the tip of the thumb under the edge of the muscle and lifting slightly. Place the index finger of the same hand in the sternal notch for orientation. Visualize an imaginary line passing just deep to the thumb of that hand and aiming at the index finger (Fig. 8.4B). Infiltrate the skin with local anesthetic, then infiltrate the deeper tissues, aspirating carefully as the needle is advanced. Use this small-gauge needle to identify the internal jugular vein by aspirating venous blood about 1- to 2-cm deep to the skin. If no blood is obtained, vary the depth below the sternocleidomastoid muscle, but not the angle of the needle, until blood is obtained.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree