Vascular Disorders and Related Diseases

VASCULARIZATION OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT—OVERVIEW

The splanchnic circulation is well developed and composed of major intramural and extramural pathways. Under resting conditions, the splanchnic circulation receives 30% of the total blood flow. During the process of digestion, the superior mesenteric artery blood flow increases by more than 100%.1 Conversely, exercise reduces both resting and postprandial blood flow. The blood flow through these pathways is subject to a complex interplay of extrinsic and intrinsic controlling mechanisms including hemodynamic factors (cardiac output, systemic arterial pressure), the autonomic nervous system, hormones (vasopressin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, somatostatin), and locally produced metabolites. Alterations of the various control mechanisms can lead to occlusive or non-occlusive disease and limited or extensive ischemic damage.

VASCULARIZATION OF THE SPECIFIC SEGMENT OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT

Esophagus

The extramural arterial supply of the human esophagus is divided into three major segments, the cervical, thoracic, and abdominal esophagus, with numerous anastomoses. The pharyngoesophageal transition and cervical esophagus are supplied by the lower thyroid artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk. An additional, individually variable supply is provided by small branches of the subclavian, common carotid, vertebral, and superior thyroid arteries and the costocervical trunk. The thoracic esophagus receives blood from branches of the aorta, the bronchial arteries, and the right intercostal arteries. At the level of the bifurcation of the trachea, the main supply comes from branches of the bronchial arteries, which descend on the ventral side of the esophagus. Below the bifurcation of the trachea, the blood supply originates from two esophageal branches that arise directly from the ventral side of the aorta. Both branches run to the dorsal side of the esophagus where they anastomose with the descending branches of the lower thyroid and ascending branches of the left gastric and left lower phrenic arteries. The abdominal esophagus is supplied by esophageal branches of the left gastric and left lower phrenic arteries. An additional blood supply may be provided by branches of the aorta, the splenic artery, the celiac trunk, and an aberrant left hepatic artery.2, 3

The intramural arterial pattern is characterized by a well-developed subepithelial capillary network in the stromal papillae of the mucosa (intraepithelial channels), supplied by a prominent submucosal arterial plexus, composed of longitudinally oriented arteries with lateral anastomoses. Submucosal arteries are formed by penetrating branches arising from a minor extrinsic plexus in the adventitia. These branches pass through the muscle layer and give off branches to the muscle tissue and the myenteric plexus.4, 5

Esophageal veins are classified into three groups: (a) intrinsic veins including subepithelial and submucosal veins, which join the gastric veins below, and perforating veins, which pierce the muscular wall to join the extrinsic veins; (b) extrinsic veins formed by the union of groups of perforating veins, which join the left gastric vein below and the systemic veins above; and (c) venae concomitantes, which run longitudinally in the adventitia.6, 7

The subepithelial or superficial venous plexus drains the stromal papillae; lies in the lamina propria, close to the epithelium; and extends over the whole length of the esophagus.6 At the esophagogastric junction, the veins lie predominantly superficially in the lamina propria.7, 8, 9 Numerous small veins perforate the muscularis mucosae to join larger veins of the submucosal plexus (deep intrinsic veins) and constitute the palisades vessels seen endoscopically. The submucosal plexus consists of 10 to 15 longitudinal veins, evenly distributed around the circumference of the esophagus and connected by numerous anastomoses. In its proximal part, this plexus drains the longitudinally oriented veins from the ventral and dorsal pharyngoesophageal subepithelial plexus. At the distal end of the esophagus, the longitudinal submucosal veins increase in number but decrease in diameter. At the cardia, they become tortuous and aggregate in the longitudinal folds of the mucosa before joining the submucosal veins of the stomach. Perforating veins arise from the longitudinal submucosal plexus and pass through the muscle layer, which they drain also, at regular intervals.

The greater extrinsic periesophageal veins include two larger and several smaller veins. The larger veins run longitudinally on the outer surface in close proximity to the vagus nerves and connect the left gastric vein to the azygos or hemiazygos veins. Other veins are the cervical periesophageal veins draining into the inferior thyroid, vertebral, and deep cervical veins; small esophageal veins at the cardia joining the superior and inferior phrenic veins; and small abdominal esophageal veins draining into the left gastric vein as well as the vena phrenica inferior, gastroepiploica, and splenica.6

Stomach, Small Intestine, and Large Intestine

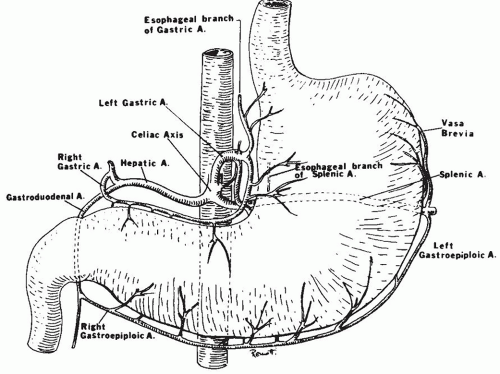

Intramural circulation. The gastric blood supply is derived from the common hepatic, left gastric, and splenic arteries arising from the celiac trunk (Fig. 2-1). The fundus and left margin of the greater curve are supplied by short gastric arteries derived from the splenic artery. The right gastric artery and the right gastroepiploic artery supply the lesser and distal greater curve, respectively. The proximal greater curve is supplied by the left gastroepiploic artery and arteries from the splenic artery. These vessels form two extrinsic arcading anastomotic loops. The loops give off a series of short branches to the anterior and posterior walls. They form a subserosal plexus.10, 11, 12 Perforating branches originating from this plexus pass through the external muscle layers to reach a richly anastomotic submucosal arterial plexus. Small side branches are given off to the external muscle layers and to Auerbach’s plexus en route, but the majority of arterioles to the external muscle come from the submucosal plexus. The mucosa is supplied by small branches from the submucosal plexus, which pass perpendicularly through the muscularis mucosae. In the lamina propria, the arterioles branch into capillaries, which run toward the lumenal surface between the gastric glands. There are frequent cross anastomoses between adjacent capillaries. Just underneath the surface epithelium, the capillaries form a polygonal network around the necks of the gastric pits.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Mucosal venules drain into the submucosal venous plexus, which is continuous with a similar plexus in the esophagus and duodenum. In the gastric cardia the submucosal venous plexus is composed of a series of parallel veins oriented toward the esophagogastric junction. Drainage of the muscle layers occurs to the submucosal venous plexus and partly to perforating veins, which pass to subserosal veins. The latter drain toward the portal system.

The duodenum is supplied chiefly by the pancreaticoduodenal artery. The jejunum and the ileum are supplied by a dozen branches of the superior mesenteric artery. These branches divide and anastomose several times in the mesentery forming arcades. The last of these forms a marginal artery along the small intestine. The marginal artery is defined as the artery closest to and parallel with the wall of the intestine. From the marginal artery, blood reaches the intestine by way of short, straight branches or “vasa recta.” They penetrate the external muscle layers to reach a profusely anastomotic submucosal arterial plexus from which arterioles originate for the mucosa, sub-mucosa, and muscular layers. The submucosal plexus gives off two types of mucosal branches: long or villous arterioles and short or cryptal ones. Arterioles to the villi pass without branching in the lamina propria. At the tip of the villus, the arteriole splays into a network of capillaries that subsequently course down along the sides of the villus in a fountain-like pattern. The crypts receive their arterial supply adjacent to the muscularis mucosae. The lymphoid tissue is supplied by the submucosal plexus through interfollicular arteries between the lymphoid follicles and through follicular arterioles originating from the interfollicular arteries. Venous drainage of each of the small intestinal capillary beds passes to the submucosal venous plexus, which anastomoses both longitudinally and

circumferentially in the bowel wall. This plexus is drained by short veins, which penetrate the external muscle layers, chiefly along the mesenteric margin and then pass to branches of the superior mesenteric vein in the mesentery. The superior mesenteric vein receives venous drainage of the distal duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, the appendix and cecum, the ascending and transverse colons and a right gastroepiploic vein draining the stomach, before joining the splenic vein to form the hepatic portal vein.13, 15, 18

circumferentially in the bowel wall. This plexus is drained by short veins, which penetrate the external muscle layers, chiefly along the mesenteric margin and then pass to branches of the superior mesenteric vein in the mesentery. The superior mesenteric vein receives venous drainage of the distal duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, the appendix and cecum, the ascending and transverse colons and a right gastroepiploic vein draining the stomach, before joining the splenic vein to form the hepatic portal vein.13, 15, 18

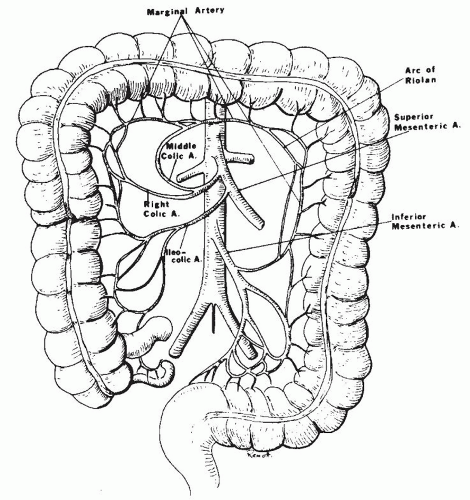

The ascending and transverse colons are supplied by three branches of the superior mesenteric artery (ileocolic and right and middle colic arteries), whereas the splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid are nourished by branches of the inferior mesenteric artery (left colic and sigmoid arteries). These vessels form arcades that are less numerous and complex than those in the small intestine. Within 2 cm of the colon wall, a single large anastomotic marginal artery is formed. This marginal artery runs retroperitoneally, extending from the ileocecal junction down to and into the sigmoid mesocolon close to its attachment to the colon wall, thus forming an anastomotic channel between ileocolic; right, middle, and left colic; and sigmoid arteries. The rectum has a richly anastomosing arterial system derived from the inferior mesenteric and internal iliac arteries. Through the superior rectal artery, it forms an anastomosis with the marginal artery of the colon. Short vasa recta pass from the marginal artery to the colon wall, with few or no anastomoses en route. Upon reaching the wall, they divide to form subserosal branches, which pass circumferentially around the bowel wall, and other branches, which form a subserosal anastomosing plexus. The subserosal plexus gives off branches that traverse the external muscle coat to reach the submucosal arterial plexus. There is extensive anastomosis in the submucosa both longitudinally and circumferentially. Arteriolar branches from the submucosal plexus penetrate the muscularis mucosae and then break up in a leash of capillaries. These capillaries ascend along the glands and reach the surface of the mucosa where they form a honeycomb pattern around the openings of the glands, just beneath the surface epithelium. The muscularis contains capillaries derived from both the subserosal and submucosal plexuses and is perforated by larger arteries coming from the serosa and subserosa. The venous drainage largely parallels the arterial supply.13, 19

Extramural (Splanchnic) circulation. The celiac trunk is a short (2 cm) but larger caliber (5-8 mm) artery, which arises from the front of the aorta. It divides almost immediately into three branches: the common hepatic, splenic, and left gastric arteries. There are however many variations of the typical origin. The most striking of these is a common origin of the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery in a celiacomesenteric trunk (in ˜2% of cases). In this situation, a single artery is the sole source of vascularization of the supramesocolic organs. Collateral flow is possible only from the inferior mesenteric, phrenic, esophageal, and retroperitoneal arteries.10

The common hepatic artery arises on the right side of the celiac trunk, giving off branches to the stomach, duodenum, and pancreas. The right gastric artery arises from hepatic artery and less frequently from the gastroduodenal artery (8%). It descends to the pylorus along the lesser curvature of the stomach where it usually anastomoses with the left gastric artery. The right gastric artery frequently gives rise to the supraduodenal artery (of Wilkie).

The gastroduodenal artery usually arises from the common hepatic artery (75%) but may arise from the left or right hepatic artery or superior mesenteric artery. It divides into the right gastroepiploic and the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. This artery anastomoses with the posterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery to form the pancreaticoduodenal arcade supplying the posterior surface of the entire duodenum and the head of the pancreas. The anterior pancreaticoduodenal arcade is formed by the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and the anterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which arises from the superior mesenteric artery. The right gastroepiploic artery is the final continuation of the gastroduodenal artery. After supplying one or more branches to the pylorus, it passes to the left along the greater curvature of the stomach. Ascending branches supply the greater curvature of the stomach and anastomose with descending branches of the right and left gastric arteries.

The left gastric artery courses toward the gastric cardia. It supplies part of the stomach and the inferior esophagus. The anastomosis with the right gastric artery may be absent.

The splenic artery from the celiac artery gives off branches to the pancreas and stomach. Often, a branch of the dorsal pancreatic artery descends below the inferior border of the pancreas to communicate with the superior mesenteric artery. Occasionally, this branch gives rise to the middle colic artery (artery of Riolan). The left gastroepiploic artery arises from the splenic artery prior to its terminal divisions or from a terminal division itself. It gives off the left epiploic artery, which anastomoses with the right epiploic artery, a branch of the right gastroepiploic artery, to form the arcus epiploicus magnus of Barkow, in the great omentum below the colon. Short gastric arteries originate from the distal splenic artery and supply the fundus and cardia of the stomach.

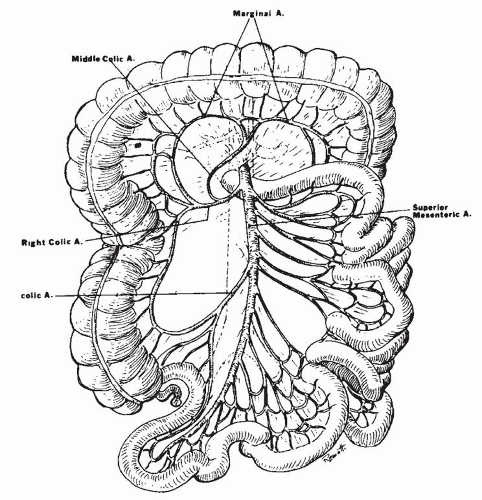

The superior mesenteric artery originates from the aorta at the level of the first lumbar vertebra, behind

the body of the pancreas (Fig. 2-2). It emerges from under the lower border of the pancreas, passes forward anteriorly over the upper border of the third portion of the duodenum, and descends anteriorly into the mesentery. Usually, the middle colic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery just before it enters the mesentery. The middle colic artery can arise as a separate branch or be derived from a common right colic-middle colic trunk (53% of the cases). Occasionally, it arises directly from the celiac artery. When the middle colic artery has a large branch running parallel and posterior to it in the transverse mesocolon, this branch is often described as the arc of Riolan. The right colic artery can arise directly (38%) from the superior mesenteric artery. The middle and right colic arteries supply the right half of the transverse colon and the ascending colon. Within the mesentery, the superior mesenteric artery courses to the right iliac fossa, curving to the left to end in the ileocolic artery by forming an anastomosis. Major side branches of the superior mesenteric artery originating usually on the right side are the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries supplying the lower part of the duodenum. These arteries connect with the superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery can also arise from or can be in common with the first jejunal artery. To the left, four to six jejunal arteries and nine to thirteen intestinal branches that supply the ileum can be identified. These are often called “intestinal arteries.”

the body of the pancreas (Fig. 2-2). It emerges from under the lower border of the pancreas, passes forward anteriorly over the upper border of the third portion of the duodenum, and descends anteriorly into the mesentery. Usually, the middle colic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery just before it enters the mesentery. The middle colic artery can arise as a separate branch or be derived from a common right colic-middle colic trunk (53% of the cases). Occasionally, it arises directly from the celiac artery. When the middle colic artery has a large branch running parallel and posterior to it in the transverse mesocolon, this branch is often described as the arc of Riolan. The right colic artery can arise directly (38%) from the superior mesenteric artery. The middle and right colic arteries supply the right half of the transverse colon and the ascending colon. Within the mesentery, the superior mesenteric artery courses to the right iliac fossa, curving to the left to end in the ileocolic artery by forming an anastomosis. Major side branches of the superior mesenteric artery originating usually on the right side are the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries supplying the lower part of the duodenum. These arteries connect with the superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery can also arise from or can be in common with the first jejunal artery. To the left, four to six jejunal arteries and nine to thirteen intestinal branches that supply the ileum can be identified. These are often called “intestinal arteries.”

They divide into two branches, forming a first-order arcading anastomosis with the neighboring branches. Subsequent anastomes form second- to fourth-order arcades. Branches of these arcades finally form the marginal artery. The marginal artery may thus be composed of arteries that range from third- or fourth-order arcades to the parent colic artery itself. The middle colic artery is often the marginal artery for the major portion of its distribution. Fine branches originating from the marginal artery reach the bowel wall as “vasa recta.” The vasa recta of the small intestine are shorter, closer together, and less straight in appearance than the large bowel vasa recta. The terminal branch of the superior mesenteric artery is the ileocolic artery. It distributes branches to the terminal ileum, the cecum, and the lower third or half of the ascending colon. In its distal distribution the ileal and colic branches of the ileocolic artery often form an “ileocolic loop.” The anterior and posterior cecal arteries and the appendicular artery arise separately from this loop.

The inferior mesenteric artery arises from the aorta anteriorly at the level of the third lumbar vertebra (Fig. 2-3). Major side branches are the left colic artery and the sigmoid arteries. The descending branch of the inferior mesenteric artery becomes the superior rectal artery. The left colic artery is usually an ascending branch from the inferior mesenteric artery. This branch bifurcates at the splenic flexure, its right branch joining the middle colic artery from the superior mesenteric artery and its left branch joining the marginal artery. Sigmoid arteries can originate from the ascending branch in common with the left colic or arise from a descending branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. A few sigmoid arteries may arise from a middle branch. The number of sigmoid arteries varies from one to five. The superior rectal artery divides

into two branches of unequal size at the level of the second or third sacral vertebra, commonly at the bottom of the pouch of Douglas. The larger right branch divides into several branches, which descend on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the rectal ampulla. The smaller left branch deviates to the left and supplies the lateral and anterior surfaces. In contrast to the small and large intestinal arteries, the branches of the rectal arteries do not form arcades but enter the gut wall directly and independently.

into two branches of unequal size at the level of the second or third sacral vertebra, commonly at the bottom of the pouch of Douglas. The larger right branch divides into several branches, which descend on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the rectal ampulla. The smaller left branch deviates to the left and supplies the lateral and anterior surfaces. In contrast to the small and large intestinal arteries, the branches of the rectal arteries do not form arcades but enter the gut wall directly and independently.

The branches of the superior rectal artery further anastomose with the middle and inferior rectal arteries originating respectively from the internal iliac and pudendal arteries.10, 11, 12