KEY POINTS

In the surgical treatment of invasive bladder cancer, a thorough lymph node dissection is essential.

Patients with testicular cancer without radiographic evidence of metastasis often harbor microscopic occult deposits of disease and require either adjuvant treatment or very close surveillance.

Partial nephrectomy is the mainstay of treatment for small renal masses, whereas radical nephrectomy provides a survival benefit in the setting of metastatic disease.

The vast majority of renal trauma can be treated conservatively, with early surgical intervention reserved for persistent bleeding, renal vascular, or ureteral injuries.

Distal ureteral injuries should only be treated with ureteroneocystostomy (bladder reimplantation) because of the high failure rate of distal uretero-ureterostomies.

Extraperitoneal bladder ruptures can be treated conservatively, but intraperitoneal ruptures typically require surgical repair.

Nearly all episodes of acute urinary retention can be treated with conservative measures such as decreasing narcotic usage and increasing ambulation.

Testicular torsion is an emergency where successful testicular salvage is inversely related to the delay in repair, so cases with a high degree of clinical suspicion should not wait for a radiologic diagnosis.

Fournier’s gangrene is a potentially lethal condition that requires aggressive débridement and close follow-up due to the frequent need for repeat débridement.

Most small ureteral calculi will pass spontaneously or with the use of medical expulsive therapy, but larger stones (>6 mm) are better treated with ureteral stenting or lithotripsy.

ANATOMY

The anatomic structures that fall under the purview of genitourinary surgery are the adrenals, kidneys, ureters, bladder, prostate, seminal vesicles, urethra, vas deferens, penis, and testes. Some of these structures are situated outside the peritoneum, but urologic surgery frequently involves intraperitoneal approaches to the kidney, bladder, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Furthermore, urologists must be familiar with the techniques of intestinal surgery for the purposes of urinary diversion and bladder augmentation.

The kidneys are paired retroperitoneal organs that are invested in a fibro-fatty layer: fascia of Zuckerkandl posteriorly and Gerota’s fascia anteriorly. Posterolaterally, the kidneys are bordered by the quadratus lumborum and posteromedially by the psoas muscle. Anteriorly, they are confined by the posterior layer of the peritoneum. On the left, the spleen lies superolaterally, separated from the kidney and Gerota’s fascia by the peritoneum. On the right, the liver is situated superiorly and anteriorly and also is separated by the peritoneum. The second portion of the duodenum is in close proximity to the right renal vessels, and during right renal surgery, it must be reflected anteromedially (Kocherized) to achieve vascular control. The renal arteries, in the typical configuration, are single vessels extending from the aorta that branch into several segmental arteries before entering the renal sinus. The right renal artery passes posterior to the vena cava and is significantly longer than the left renal artery. Occasionally, the kidney is supplied by a second renal artery, an accessory renal artery, typically to the lower pole. Within the kidney, there is essentially no anastomotic arterial flow, so the kidneys are prone to infarction when branch vessels are interrupted. The renal veins, which course anteriorly to the renal arteries, drain directly into the vena cava. The left renal vein passes anterior to the aorta and is much longer than the right renal vein. This explains why most surgeons prefer to take the left kidney for living donor transplantation. The left vein is in continuity with the left gonadal vein, the left inferior adrenal vein, and a lumbar vein. These veins provide adequate drainage for the left kidney in the event that drainage to the vena cava is interrupted. The right renal vein has no such collateral venous drainage.

The collecting system of the kidney is composed of several major and minor calyces that coalesce into the renal pelvis. The renal pelvis can have either a mainly intrarenal or extrarenal position. The renal pelvis tapers into the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) where it joins with the ureter.

The adrenal glands lie superomedially to the kidneys within Gerota’s fascia. There is a layer of Gerota’s fascia between the adrenal and the kidney. However, in the presence of a tumor or inflammatory process, the adrenal can become very adherent to the kidney, and separation can be difficult. The arterial supply of the adrenals derives from the inferior phrenic, aorta, and small branches from the renal arteries. The venous drainage on the left is mainly through the inferior phrenic vein and through the left renal vein via the inferior adrenal vein. On the right, the adrenal is drained by a very short (<1 cm) vein to the vena cava. It can be avulsed by moderate traction and can be the source of troublesome bleeding.

The ureters are muscular structures that course anterior to the psoas muscles from the renal pelvis to the bladder. The blood supply of the proximal ureter derives from the aorta and renal artery and comes mainly from the medial direction. However, once it crosses the iliac vessels at the pelvic brim near where the iliac vessels bifurcate, it derives its blood supply laterally from branches from the iliac arteries. The blood supply has implications for managing ureteral injuries. Mobilizing the distal ureter for anastomosis requires releasing its lateral attachments, which results in ischemia, so for this reason, distal ureteral injuries are typically managed by anastomosing the proximal ureter to the bladder.

The ureters course along the pelvic sidewall and pass under the uterine arteries in women, making them vulnerable to injury during hysterectomy, especially in the context of pelvic bleeding. They enter the bladder at the lateral aspect of the base. They course through the bladder musculature at an oblique angle and open into the bladder at the ureteral orifices that are relatively close to the bladder outlet.

The urinary bladder is situated in the retropubic space in an extraperitoneal position. A portion of the bladder dome is adjacent to the peritoneum, so ruptures at this point can result in intraperitoneal urine leakage. The anatomic relations of the bladder are dependent on the degree of filling. A very distended bladder can project above the umbilicus. At physiologic volumes (200–400 mL), the bladder projects modestly into the abdomen. The sigmoid colon lies superolaterally and may become adherent or fistulize to the bladder secondary to diverticulitis. The rectum lies posterior to the bladder in males, whereas the vagina and uterus are posterior in females.

In males, the prostate is in continuity with the bladder neck, and the urethra courses through it. The prostate has a significant component of smooth muscle and can provide urinary continence even in the absence of the external striated sphincter. The puboprostatic ligaments connect the prostate to the pubic symphysis, and pelvic fractures often result in proximal urethral injuries due to the traction that these ligaments provide. Between the prostate and the rectum lies Denonvilliers’ fascia, which is the main anatomic barrier that prevents prostate cancer from regularly penetrating into the rectum. Just beyond the apex of the prostate is the external (voluntary) sphincter, which is part of the genitourinary diaphragm.

The penis is composed of three main bodies, along with fascia, neurovascular structures, and skin. The corpora cavernosum are the paired, cylinder-like structures that are the main erectile bodies of the penis. Proximally, they lie along the medial aspects of the inferior pubic rami in the perineum. Distally, they fuse along their medial aspects and form the pendulous penis. The corpora cavernosum consist of a tough outer layer called the tunica albuginea and spongy, sinusoidal tissue inside that fills with blood to result in erection. The two corpora cavernosum have numerous vascular interconnections, so they function as one compartment. The cavernosal arteries, which are branches of the penile artery, course through the center of the corporal sinusoidal tissue. The sinusoidal tissue is innervated by the cavernosal nerves, which are autonomic nerves that originate in the hypogastric plexus and play a critical role in erection. Before entering the penis, the cavernosal nerves travel immediately adjacent to the prostate, which explains why they often are damaged at radical prostatectomy. Injury or excess traction of these nerves may cause erectile dysfunction. On the underside of the penis lies the corpus spongiosum, which surrounds the urethra. The spongiosum does not have the same tunical layers as the corpora cavernosum, so it does not exhibit the same firmness during erection. The tip of the penis, called the glans, is in continuity with the corpus spongiosum. This highlights the point that when men develop priapism—persistent erection for greater than 4 hours unrelated to sexual stimulation—the two corpora cavernosum remain rigid while the glans (derived from the corpora spongiosum) can be soft.

Surrounding all three bodies of the penis are the outer dartos fascia and the inner Buck’s fascia. The dorsal nerves of the penis, which provide sensation to the penile skin, derive from the pudendal nerves and, along with the dorsal penile arteries, travel along the dorsum of the penis within Buck’s fascia. The neurovascular bundle of the penis must be avoided during surgical exploration of the penis for injuries or reconstruction, as injury may result in permanent erectile and/or ejaculatory dysfunction.

The scrotum is a capacious structure that contains the testes and epididymes. Because of its dependent position, significant edema can develop when a patient is fluid overloaded. Additionally, since the scrotum is capacious, any significant bleeding will result in the accumulation of large hematomas—even as large as a basketball. Beneath the skin, from superficial to deep, are the dartos, external spermatic, cremasteric, and internal spermatic fascias. These layers are not always distinct. Beneath the internal fascia are the parietal and visceral layers of the tunica vaginalis, between which hydroceles form. The visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis is adherent to the testis. The noncompliant outer testis layer is the tunica albuginea. Inside the tunica are the seminiferous tubules. The blood supply enters the testis at the superior pole by way of the spermatic cord. In addition to the vas deferens, the cord carries three separate sources of arterial blood flow—the testicular artery that arises from the aorta below the renal artery, the cremasteric artery, and the deferential artery. Interruption of one of the arteries during vasectomy or inguinal surgery will not result in ischemia to the testis. Some children are born with an undescended abdominal testicle. Often, it is difficult to derive enough length to place the testicles in the scrotum. In these instances, the testicular artery is ligated as a first-stage operation, and the testicle is then delivered into the scrotum as a second-stage procedure (i.e., Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy). Most of these testicles remain viable as a result of collaterals. However, if a patient has undergone a prior Fowler-Stephens procedure, any manipulation of the collaterals during inguinal surgery may compromise the testicle. Venous drainage parallels the arterial inflow except that the left gonadal vein drains into the renal vein rather than the vena cava. Dilation of spermatic veins is called a varicocele and may be palpable when a patient is standing or with Valsalva. They do not need to be treated unless they cause discomfort, are discovered on infertility workup, or are found in children.

UROLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

The most common form of bladder cancer in the United States is urothelial carcinoma. Tobacco use is the most frequent risk factor, followed by occupational exposure to various carcinogenic materials such as automobile exhaust or industrial solvents. However, many patients develop bladder cancer without any identifiable risks.1 Other forms of bladder cancer, such as adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, occur in distinct patient populations. Patients with chronic irritation from catheters, bladder stones, or schistosomiasis infection are at risk for the squamous cell variant, whereas those with urachal remnants or bladder exstrophy have an increased risk of adenocarcinoma. However, the aforementioned variant histology should not be confused with urothelial carcinoma with variant transformation.

Bladder cancer can be categorized into invasive and noninvasive types. Management of urothelial carcinoma varies greatly, depending on the depth of invasion. A complete transurethral resection of the bladder tumor, which allows for staging of the tumor, is the first step. The tumor should be completely removed, if possible, along with a sampling of the muscular bladder wall underlying the tumor. An exam under anesthesia should be performed for all patients with newly diagnosed bladder tumors. The exam under anesthesia can help determine clinical staging and whether there is fixation of the bladder to adjacent structures. Radiologic imaging of most bladder tumors is of limited benefit in determining the presence, grade, or size/stage of a bladder tumor. However, in the presence of a known bladder tumor, unilateral or bilateral hydronephrosis is an ominous sign of locally advanced disease (at least muscle-invasive bladder cancer).2 Computed tomography (CT) scans do provide valuable information regarding metastatic involvement of pelvic lymph nodes, liver, or lung. Historically, 25% of patients with preoperative CT scans demonstrating no evidence of lymphatic spread will actually have lymph node involvement during radical cystectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. The utility of a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan has emerged as an important imaging modality to minimize this rate to 5% to 10%. For patients who have disease invading into bladder muscle (T2), immediate (within 3 months of diagnosis) cystectomy with extended lymph node dissection offers the best chance of survival. Additionally, surgeons should send lymph node specimens in separate packets and not en bloc in an effort to increase nodal yield. Current long-term cure for those presenting with clinically localized disease has not significantly changed over the last two decades.3 The addition of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy in those without discernible metastatic spread is gaining increasing acceptance and does provide a survival benefit.4 Patients with limited lymph node involvement may be cured with surgery alone, but those with extensive lymph node involvement have a dismal prognosis.

Patients have multiple reconstructive options, including continent and noncontinent urinary diversions. The orthotopic neobladder has emerged as a popular urinary diversion for patients without urethral involvement. This diversion type involves the detubularization of a segment of bowel, typically distal ileum, which is then refashioned into a pouch that is anastomosed to the proximal urethra (neobladder) or to the skin (continent cutaneous diversion). Detubularization decreases intrapouch filling pressure, which improves urinary storage capacity. In the case of a neobladder, the external sphincter is still intact, and voiding is achieved through sphincteric relaxation and a Valsalva maneuver. In the case of the continent cutaneous diversion, patients attain continence by utilizing a bowel segment (appendix or tapered small bowel) that has a high length-to-lumen ratio. The most common diversion is noncontinent, the ileal conduit, whereby a segment of distal ileum is isolated with one end brought out through the abdominal wall as a urostomy. Ileal conduits are preferred for renal insufficiency because urine is not “stored” and therefore has less time in contact with the absorptive surface of the ileal segment. Conduits are also used when the bladder is unresectable, but urinary diversion is necessary due to intractable bleeding, severe voiding pain, and hydronephrosis. Each segment of bowel that is used offers its own advantages and inherent complications.

Patients with non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (confined to the bladder mucosa or submucosa) can be managed with transurethral resection alone and adjuvant intravesical (instilled into the bladder) chemotherapy/immunotherapy. The use of these intravesical agents is critical since patients with non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer are at risk for tumor recurrence and progression. Tumor grade is extremely important in assessing the risk of disease progression. Those patients with high-grade disease or recurrent tumors can be treated with intravesical agents such as bacille Calmette-Guérin or mitomycin C. These agents decrease risk of progression and recurrence, by induction of an effective immunologic antitumor response in the case of bacille Calmette-Guérin and through direct cytotoxicity for mitomycin C. Those patients at high risk of progression who fail conservative therapy should be offered cystectomy. Because upper tract recurrence is fairly common (up to 17% of patients with carcinoma in situ), surveillance must be performed with retrograde pyelograms or CT urograms.

The typical surgical approach for cystectomy is a lower midline incision from just above the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. This allows adequate exposure of the pelvic contents, iliac vessels, and lower abdominal cavity. The peritoneum between the median umbilical ligaments (urachal remnant) also is taken with the specimen. In men, the prostate is removed with the bladder. In women, the uterus, ovaries (in postmenopausal women), and anterior wall of the vagina are removed with the bladder. The vagina may be spared, depending on the location and extent of the tumor, but significantly more operative bleeding results. Robotic approaches for cystectomy are increasingly used, but the urinary diversion is still usually performed through an open incision. The benefits of the robotic portion are decreased blood loss during the pelvic dissection (due to pneumoperitoneum) and the shortening of the time that the abdomen is open. However, recent evidence (randomized controlled trials of open versus robot-assisted radical cystectomy) did not demonstrate any difference in oncologic efficacy or complication rates.

Complications of bladder cancer surgery involve bladder perforation during transurethral resection of the bladder tumor, which requires catheter drainage for several days if small (common) or open repair if large and intraperitoneal (rare). Cystectomy and urinary diversion may result in prolonged ileus, bowel obstruction, intestinal anastomotic leak, urine leak, or rectal injury. A urine leak from the ureteroileal anastomoses is a common cause of ileus, intra-abdominal urinoma, abscess formation, and wound dehiscence. Deep venous thrombosis is common after cystectomy5 due to the advanced age of most patients, proximity of the iliac veins to the resection and lymph node dissection, and the presence of malignancy. Pulmonary embolism is one of the leading causes of death in the perioperative period after radical cystectomy. The utility of subcutaneous heparin in the perioperative period can minimize the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Testicular cancer is the most common solid malignancy in men age 15 to 35 years.6 Most men are diagnosed with an asymptomatic enlarging mass (Fig. 40-1). A major risk for the development of testicular cancer is cryptorchidism. Although the debate continues over whether early surgical intervention to bring an undescended testis into the scrotum alters the future risk of cancer, it is generally accepted that doing so allows much easier monitoring for the development of a testicular mass.

Most neoplasms arise from the germ cells, although non–germ cell tumors arise from Leydig’s or Sertoli’s cells. The non–germ cell tumors are rare and generally follow a more benign course. Germ cell cancers are categorically divided into seminomatous and nonseminomatous forms that follow different treatment algorithms.

Since the vast majority of solid testicular masses are cancerous, any observed mass on physical examination and/or documented on ultrasound is malignant until proven otherwise. Initial studies must include tumor markers, including α-fetoprotein, β-human chorionic gonadotropin, and lactate dehydrogenase. Elevated tumor markers are found almost exclusively in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, although up to 10% of patients with localized seminomas and 25% with metastatic seminomas will have a modest rise in β-human chorionic gonadotropin. Chest and abdominal imaging must be performed to evaluate for evidence of metastasis. The most common site of spread is the retroperitoneal lymph nodes extending from the common iliac vessels to the renal vessels, and abdominal imaging should be performed in all patients. There is no role for percutaneous biopsy of testicular masses due to (a) the risk of seeding the scrotal wall; (b) changing the natural retroperitoneal lymphatic drainage of the testicle (because the testes have a remarkably predictable pattern of lymphatic drainage); and (c) the propensity of a testicular mass being cancerous. In cases where metastatic disease to the testicle is suspected, an open testicular biopsy by delivery of the testicle through the inguinal canal is recommended. Lymphoma (especially among the elderly) may involve one or both testes. Often, evidence of lymphoma usually is present elsewhere in the body, although relapses may be isolated to the testes.

Even in the absence of enlarged lymph nodes on CT imaging (stage I), occult micrometastatic disease is often present (30% of the time), so adjuvant surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy is offered. However, active surveillance protocols have been gaining traction for both seminoma and nonseminomatous tumors. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is potentially curative in the setting of limited lymph node involvement and has been the preferred adjuvant treatment of those with stage I nonseminomatous disease. Alternatively, patients with stage I nonseminomatous tumors can also choose to receive two cycles of chemotherapy. Pure seminoma is exquisitely radiosensitive, and stage I, IIa, and IIb disease can be treated with external-beam radiation to the retroperitoneal nodes. However, a single dose of carboplatin for stage I seminoma was found to be just as effective as radiation therapy. Both forms of germ cell tumors, in the setting of disseminated disease or large bulky lymph nodes, are best treated with four cycles of chemotherapy. However, teratoma frequently is a component of retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis, and it is not responsive to chemotherapy or radiation and can demonstrate aggressive malignant degeneration. Postchemotherapy RPLND for residual masses can be challenging. Large bulky metastases may encase the great vessels, and vascular graft placement after resection occasionally is required.

For orchiectomy, an inguinal incision is made over the external ring and carried laterally over the internal ring. It is important to not violate the scrotal skin during orchiectomy, for fear (mostly theoretical) of altering the lymphatic drainage of the testis. For RPLND, a midline incision usually is made from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus for most patients with stage I disease. If it is in a setting of a postchemotherapy residual mass, the incision is extended down to the pubic symphysis. The use of robotic-assisted RPLND is rarely used for stage I nonseminomatous disease, although with increasing demand for minimally invasive surgery, one would anticipate that it will be the happy compromise for those who wish to avoid a major incision but are not interested in active surveillance or systemic chemotherapy.

Complications of testicular cancer surgery include scrotal hematoma formation, which can be prevented by meticulous hemostasis. Complications after RPLND include bowel obstruction; excessive bleeding, particularly from retrocaval lumber veins; and chylous ascites. Patients who undergo a full, bilateral RPLND often suffer from ejaculatory dysfunction due to the interruption of the descending postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers that are involved in seminal emission. For this reason, right and left templates have been developed that limit bilateral dissection (especially below the inferior mesenteric artery) and preserve some of these nerves with a low risk of leaving residual microscopic cancer.7

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a malignancy of the renal epithelium that can arise from any component of the nephron (Fig. 40-2). In 2012, there were over 64,000 new cases in the United States, with over 13,000 deaths.8 With the widespread use of imaging for many medical complaints, a stage migration has led to an increased incidence of small renal masses.9 Surprisingly, this has not led to lower mortality rates. Various histologic subtypes include clear cell, papillary (types I and II), chromophobe, collecting duct, and unclassified forms. Collecting duct and unclassified forms have dismal prognoses and do not routinely respond to systemic therapy. Benign lesions, common in the setting of a small renal mass, include oncocytomas and angiomyolipomas. Renal tumors are usually solid, but they also can be cystic. Simple cysts are very common and are not malignant, but more complex cysts may be malignant. The Bosniak classification system, based on septations, calcifications, and enhancement, is used to assess the likelihood of malignancy (Table 40-1).10

| CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION | RISK OF MALIGNANCY/MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| I | Thin-walled cyst with water density with no septations or calcifications. | 0%/nonsurgical |

| II | Thin-walled cyst with few hairline septa that may contain fine or very limited thick calcifications. Also includes homogeneously hyperdense cysts <3 cm. | 0%/nonsurgical |

| II F (follow) | Multiple hairline or slightly thickened septa without measurable enhancement. May contain nodular calcification. Also includes hyperdense cysts >3 cm. | ∼5%/should be followed for progression |

| III | Irregular or smooth thickened walls or septa with measurable enhancement. | ∼50%/surgical |

| IV | Same as III, but with enhancing solid components. | ∼100%/surgical |

Most cases of RCC are sporadic, but many hereditary forms have been described. These syndromes frequently involve a germline mutation in a tumor suppressor gene. von Hippel-Lindau disease is associated with multiple tumors including clear cell RCC (Fig. 40-3). The involved gene, vhl, also frequently is mutated or hypermethylated in sporadic RCC.11 Other rare forms include Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, where patients get oncocytomas or chromophobe tumors. Patients with hereditary papillary RCC and hereditary leiomyomatosis develop papillary RCC.

The most common sites of metastasis are the retroperitoneal lymph nodes and lungs, but liver, bone, and brain also are common sites of spread. Up to 20% to 30% of patients may present with metastatic disease, in which case, surgical debulking can improve survival, as shown in randomized controlled trials.12,13 Patients with all but the smallest renal masses should undergo testing for the presence of metastatic disease including chest CT, bone scan, and liver function tests.

Patients with localized disease may be cured with either partial or radical nephrectomy (Fig. 40-4). The oncologic efficacy of partial nephrectomy (nephron sparing) appears to be similar to that of radical nephrectomy. However, patients with larger tumors or with a more central tumor location may be at increased risk for surgical complications. Nephron-sparing surgery should be considered in all patients, if feasible, as those patients undergoing a radical nephrectomy are at risk for future chronic kidney disease.14 The lack of harm from nephrectomy due to malignancy has been extrapolated from the fact that kidney donors do not routinely develop renal insufficiency. However, kidney donors are a highly selected group, and patients with renal tumors are typically older and have more comorbidities. Additionally, the risk of contralateral RCC is 2% to 3% in most series,15 and a partial nephrectomy may prevent the future need for dialysis in case of a contralateral kidney tumor. While we should all strive to preserve as many nephrons as possible, we do not have level 1 evidence that supports the use of partial nephrectomy over radical nephrectomy for patients with small renal masses.

Minimally invasive techniques for renal surgery have greatly changed the field of kidney cancer. Laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic renal surgery allows for more rapid convalescence and decreased narcotic requirements. While laparoscopic partial nephrectomy is challenging and is performed only in experienced hands due to its associated high rate of complications, the advent of robot-assisted surgery has changed the landscape. Surgeons are now capable of performing intracorporeal suturing with much greater ease. Ablative techniques such as cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation are also popular choices, especially among those who are poor surgical candidates. However, long-term results from these techniques are currently lacking due to their recent development. Active surveillance is another viable alternative for small renal masses, especially in patients with multiple comorbidities or advanced age. Most small renal masses are low grade with a slow growth rate, and patients very rarely progress to metastatic disease after limited follow-up of 2 to 3 years.16

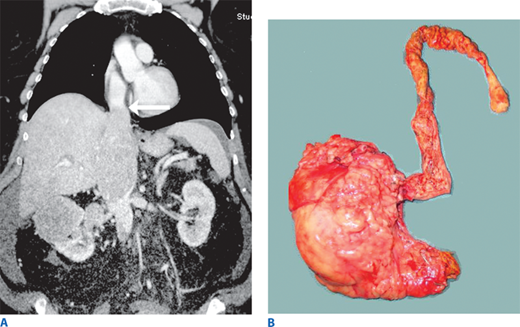

Up to 10% of RCC invades the lumen of the renal vein or vena cava. The degree of venous extension directly impacts the surgical approach. Patients with thrombus below the level of the liver can be managed with cross-clamping above and below the thrombus and extraction from a cavotomy at the insertion of the renal vein (Fig. 40-5A). Usually, the thrombus is not adherent to the vessel wall. However, cross-clamping the vena cava above the hepatic veins can drastically reduce cardiac preload, and therefore, bypass techniques often are necessary. For thrombus above the hepatic veins, a multidisciplinary approach with either venovenous or cardiopulmonary bypass is necessary. In cases of invasion of the wall of the vena cava or atrium, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest may be used to give a completely bloodless field. Tumor thrombus embolization to the pulmonary artery is a rare but known complication during these cases and is associated with a high mortality rate (Fig. 40-5B). For cases of extensive tumor thrombus, intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography should be considered for monitoring and assessment of possible thrombus embolization. If a thrombus embolization occurs, a sternotomy/cardiopulmonary bypass with extraction of the thrombus may be life saving.

Figure 40-5.

Inferior vena cava thrombus. A. A multidetector computed tomography image displaying a tumor thrombus extending above the diaphragm (arrow) arising from a right renal mass. B. An en bloc removal of a different right renal mass with a tumor thrombus that extended to the pulmonary artery. This patient is alive 6 years after surgery.

Patients undergoing resection of localized renal masses are at substantial risk of future recurrence. Many predictive features have been recognized, but the most widely accepted prognostic findings are tumor stage, grade, and size, each of which exerts an independent effect on recurrence. Isolated solitary recurrences, either local or distant, can be resected with long-term disease-free rates approaching 50%.17

Nephrectomy, either partial or radical, can be performed through a number of surgical approaches. Flank incisions over the eleventh or twelfth ribs from the anterior axillary line to the lateral border of the rectus muscle provide access to the kidney without entering the peritoneum. However, entry into the pleura is not uncommon. If small, the pleurotomy usually can be closed without need for a chest tube. The anterior subcostal approach also is used for nephrectomy. There is no risk for pleural entry, but this incision is transperitoneal, so ileus is somewhat more likely. Laparoscopic nephrectomy is now common, and robot-assisted laparoscopic partial nephrectomy is gaining significant traction in the management of small renal masses. For large tumors, particularly on the right side where the liver makes exposure of the tumor more difficult, a thoracoabdominal approach is very helpful. In these cases, the flank incision is made over the tenth rib and carried further posterior and anterior than a typical flank incision. The chest and abdominal cavities are intentionally entered for maximum exposure, and the diaphragm is partially divided in a circumferential fashion, which allows cephalad retraction of the liver. A chest tube is used postoperatively. The adrenal gland is no longer routinely removed unless the tumor is adherent to it. The benefit of lymph node dissection when the nodes are not clinically involved is uncertain.

Complications of radical nephrectomy include bleeding, pneumothorax, splenic injury, liver injury, and pancreatic tail injury. Partial nephrectomy has the added risks of delayed bleeding and urine leak. Ileus is not common when the peritoneal cavity is not entered.

Prostate cancer is the most common nonskin malignancy in men, with an incidence of approximately 200,000 per year. Yearly screening consisting of digital rectal exam and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing has been a topic of much debate. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has advised against the routine use of prostate cancer screening. The American Urological Association has advised for screening for men 55 to 69 years of age. Patients of African American descent or those with a family history of prostate cancer should be considered for screening at an earlier age (as early as 40). Men with abnormal digital rectal exams or PSA elevation have an indication for prostate biopsy to determine the presence of the disease. With the advent of PSA screening, prostate cancer has experienced a stage migration, with most cases now discovered locally confined within the prostate. The majority of patients with prostate cancer will not die of the disease by 10 to 15 years, whether it is treated at diagnosis or not. However, those undergoing initial treatment have improved cancer-specific survival.18

Prostate cancer is graded according to the Gleason scoring system.19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree