Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. In this chapter, the endoscopic anatomy and the technical maneuvers necessary for safe visualization of the upper gastrointestinal tract are described. For detailed information on endoscopic findings, indications, and technique of biopsy, as well as therapeutic endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract, the reader is referred to several excellent texts listed in the references.

Steps in Procedure

Produce adequate topical anesthesia of the oropharynx

Intravenous sedation is generally used

Position patient with left side down

Gently introduce scope into mouth, with slight curve to facilitate passage into esophagus (controls unlocked)

The esophagus may be seen as a slit at the “base” of the “triangle” formed by the vocal cords

Pass the scope through the sphincter as the patient swallows

The esophageal lumen should then be visible—pass the scope under direct vision to the distal esophageal sphincter

Gentle pressure passes the scope into the stomach

Inflate the stomach with air and check all areas, including retroflexion to visualize the cardia

Hug the lesser curvature and pass through the pylorus to visualize the duodenum

Intraoperative small bowel endoscopy:

Surgeon creates a balloon of air around the tip of the scope

Pass the scope by gently reefing the bowel over the scope

Mark any pathology with a fine silk suture on the outside of the bowel

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Perforation

Missed lesions resulting from incomplete examination

List of Structures

Pharynx

Nasopharynx

Oropharynx

Laryngopharynx

Esophagus

Stomach

Cardia

Body

Fundus

Pylorus

Duodenum

Small intestine

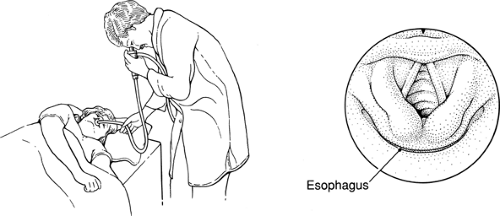

Position of the Patient and Initial Passage of the Endoscope (Fig. 45.1)

Technical Points

Thorough topical anesthesia of the pharynx is essential. This is best produced with the patient sitting facing the examiner and holding a basin.

The patient should then be placed in the left lateral decubitus position. Intravenous sedation is a useful adjunct and may be used at this point. In addition to the suction channel of the endoscope, a Yankauer suction apparatus should be available at the patient’s head to avoid aspiration if the patient vomits.

Place a bite block over the endoscope. Check to make certain that the controls of the endoscope are not locked. Pass the endoscope into the posterior pharynx. Use the index and middle fingers of your nondominant hand to guide the endoscope and keep it in the midline. Ask the patient to swallow. Gently advance the endoscope as you feel the sphincter open as

swallowing is initiated. Because this maneuver is done essentially blindly, it must be done gently. If the endoscope deviates from the midline, it will probably enter the left or right piriform sinus, a blind diverticulum. Forced attempts at passage may then result in perforation. Occasionally, the endoscope will enter the larynx; this generally results in coughing.

swallowing is initiated. Because this maneuver is done essentially blindly, it must be done gently. If the endoscope deviates from the midline, it will probably enter the left or right piriform sinus, a blind diverticulum. Forced attempts at passage may then result in perforation. Occasionally, the endoscope will enter the larynx; this generally results in coughing.

Anatomic Points

The pharynx, which is the vertical, tubular passage extending from the base of the skull to the beginning of the esophagus, is in open communication with the nasal, oral, and laryngeal cavities. It is customarily considered to have three components: the nasopharynx (superior to the soft palate), the oropharynx (the area extending from the soft palate superiorly to the hyoid bone inferiorly), and the laryngopharynx (the region extending from the hyoid bone to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage).

The nasopharynx communicates with the auditory tubes (whose ostia open into its lateral wall) and with the nasal cavities (through the choanae). The pharyngeal tonsils (adenoids) are located on the posterior wall of the nasopharynx. The cavity of this portion of the pharynx is always patent and is the widest part of the pharynx.

The oropharynx, sometimes called the posterior pharynx, widely communicates anteriorly with the mouth, where the cavity faces the pharyngeal aspect of the tongue. The palatine tonsils are on the lateral wall between the anterior palatoglossal arch and the posterior palatopharyngeal arch. These lymphoid tissue masses, in conjunction with the pharyngeal tonsil in the nasopharynx and with lymphoid tissue on the pharyngeal part of the tongue (lingual tonsil), form Waldeyer’s ring. The oropharyngeal isthmus can be closed by approximation of the palatoglossal arches, accompanied by retraction of the tongue. This lingual movement also occludes the lumen of the oropharynx above the bolus during swallowing.

The laryngopharynx communicates anteriorly with the opening of the larynx. Lateral to the laryngeal aditus (inlet) on either side is an elongated fossa, the piriform recess. Inferiorly, the laryngopharynx is continuous with the esophagus. This junction is the narrowest part of the pharynx.

At the pharyngoesophageal junction, the pharyngeal musculature consists of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, the thickest of the three pharyngeal constrictors. This muscle can be logically subdivided into a superior thyropharyngeus, whose fibers arise from the thyroid cartilage and are directed superomedially to insert on a posterior median raphe, and an inferior cricopharyngeus, whose fibers originate from the cricoid cartilage and pass horizontally to insert on the median raphe. During swallowing, contraction of the thyropharyngeus propels the bolus, whereas the cricopharyngeus acts as a sphincter. Failure of the cricopharyngeus to relax during swallowing can result in herniation of the mucosa between the two parts of the inferior constrictor (Zenker’s diverticulum; see Chapter 12), or a predisposition to perforation of the esophagus with the endoscope.

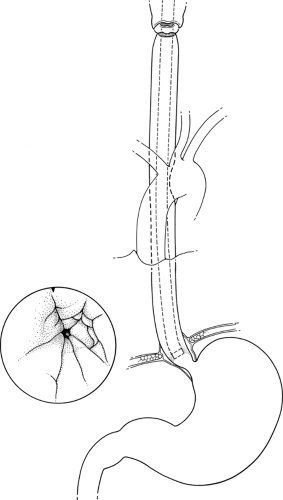

The Esophagus (Fig. 45.2)

Technical Points

After the endoscope is within the esophagus, visualize the lumen and advance the endoscope to the cardioesophageal junction under direct vision. This is a fairly straight shot and should require minimal motion of the controls. Periodic light puffs of air keep the lumen open and assist in passage of the instrument. Recognize the cardioesophageal junction by the change in color at the squamocolumnar junction (the Z line). Generally, the cardioesophageal junction lies about 40 cm from the incisor teeth. The lower esophageal sphincter, a physiologic high-pressure zone without any consistent anatomic landmark, will generally be closed. Gentle pressure with the endoscope will allow the endoscope to pass into the stomach unless the distal esophagus is narrowed by a stricture or tumor.

Anatomic Points

The esophagus, which begins at the lower border of the cricoid cartilage, is about 25 cm long. It descends through the neck and thorax just anterior to the vertebral bodies. It passes through the diaphragm at about the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra, and ends by opening into the cardia of the stomach at about the level of the eleventh thoracic vertebra. It lies in the median plane at its origin, but deviates slightly to the left until the root of the neck. At the root of the neck, it gradually deviates to the right so that, by the level of the fifth thoracic

vertebra, it is once again midline. At the seventh thoracic vertebra, it again deviates to the left, and ultimately turns anteriorly to pass through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. The thoracic esophagus also has anterior and posterior curves that follow the curvature of the vertebral column. The intraabdominal esophagus turns sharply to the left to become continuous with the stomach.

vertebra, it is once again midline. At the seventh thoracic vertebra, it again deviates to the left, and ultimately turns anteriorly to pass through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. The thoracic esophagus also has anterior and posterior curves that follow the curvature of the vertebral column. The intraabdominal esophagus turns sharply to the left to become continuous with the stomach.

The anatomic relationships of the esophagus are important. In the neck, the esophagus is posterior to the trachea and anterior to the cervical vertebra and the prevertebral muscles. Lateral to the cervical esophagus and trachea on both sides are the recurrent laryngeal nerve (in or near the tracheoesophageal groove), the common carotid artery, and the thyroid lobes. In the lower neck, the thoracic duct ascends to the left of the trachea. In the mediastinum, from superior to inferior, the esophagus has the following relationships.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree