Tube Thoracostomy, Thoracotomy, Wedge Resection, and Pleural Abrasion

M. Victoria Gerken

Phillip C. Camp

In this chapter, the basic procedure of tube thoracostomy is used to introduce chest wall anatomy. The basic thoracic surgery incision—posterolateral thoracotomy—is described in detail. Two common, simple, thoracic surgery procedures—wedge resection and pleural abrasion—are then described.

Steps in Procedure

Tube Thoracostomy

Location (interspace) is determined by nature of material to be drained

Obtain adequate local anesthesia and widely prep and drape the area

Check equipment, including drainage device, to ensure everything is ready

Make an incision one interspace below the desired interspace

Gently spread the tissues cephalad until the top of the next rib is encountered

Spread the intercostal muscles just above the rib and control the clamp as you pop into the pleural space

Spread the opening until it is large enough to admit your finger

Digitally explore the space, break down any loculations or adhesions, and confirm intrathoracic placement by palpating diaphragm

Insert the chest tube into this interspace, passing it just far enough to place the last hole within the pleural space

Connect to the tubing of the drainage device and secure tube in position

Standard Posterolateral Thoracotomy

Carefully position patient in full lateral decubitus position, padding and securing patient with care

Prepare hemithorax and drape widely

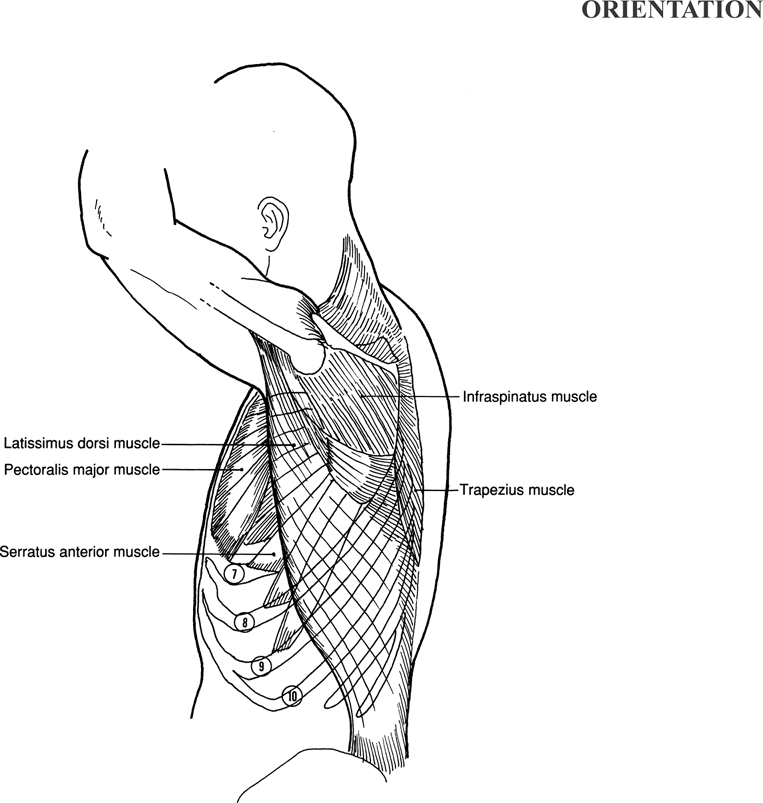

Standing at patient’s back, draw an incision from anterior axillary line (inframammary fold, for a 6th interspace thoracotomy) to a point 2 to 3 cm inferior to the inferior angle of scapula, then angled gently cephalad to end midway between spine of scapula and thoracic vertebral column

Divide subcutaneous tissues to and through muscles, preserving the paraspinal muscles

Enter the chest through 3rd, 4th, or 5th interspace depending on operation to be performed

Divide intercostals muscles and enter pleura

Extend intercostal incision and place rib spreader

At conclusion of procedure, check for air leaks and place chest tubes under direct vision

Remove rib spreader and approximate ribs with six to eight figure-of-eight pericostal sutures

Approximate muscles over chest wall

Close subcutaneous tissues and skin, secure chest tubes in place

Muscle-sparing Thoracotomy

Same incision as above, but not so long posteriorly

Divide subcutaneous tissue and free it from fascia of latissimus dorsi muscle

Mobilize latissimus dorsi muscle and serratus anterior to allow retraction of both muscles

Enter pleural space

Use two small rib spreaders placed at right angles

Wedge Resection

Identify the region to be resected

Tent up the lesion by elevating it with lung clamps

Fire stapler across region to be resected (generally two firings will be needed, at right angles to each other)

Pleural Abrasion

Resect blebs if present, using wedge resection technique, and check for air leaks

Abrade pleural surfaces briskly with dry laparotomy sponge

Hallmark Anatomic Complications

Injury to lung or diaphragm (during tube thoracostomy)

Injury to intercostal neurovascular bundle

Creation of devitalized or nonaerated remnant during wedge resection

List of Structures

Pleura

Pleural space

Intercostal space

External intercostal muscles

Internal intercostal muscles

Innermost intercostal muscles

Intercostal Neurovascular Bundle

Intercostal vein

Intercostal artery

Intercostal nerve

Diaphragm

Costal margin

Xiphoid process

Serratus anterior muscle

Endothoracic fascia

Latissimus dorsi muscle

Scapula

Trapezius muscle

Triangle of auscultation

Rhomboideus major muscle

Erector spinae muscles (paraspinous muscles)

Long thoracic nerve

|

Tube Thoracostomy

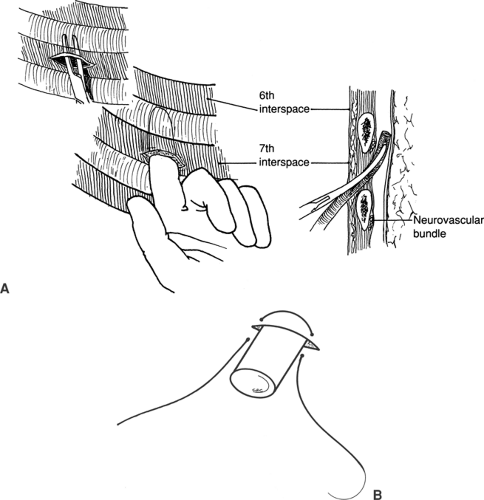

Placement of a Tube Thoracostomy (Fig. 24.1)

Technical Points

The relatively simple procedure of tube thoracostomy demands careful attention to detail. Poor performance will cause patient discomfort and underlying lung injury, and may even necessitate open thoracotomy or laparotomy for correction.

In the past, chest tubes placed for pneumothoraces were inserted in the anterior chest, causing much unnecessary discomfort for the patient and substantially increasing the risk for hemorrhage from the anterior chest wall. Current practice dictates that chest tubes for uncomplicated pleural effusions, hemothoraces, or pneumothoraces be placed between the anterior axillary line and the midaxillary line, resulting in best results and minimum pain to the patient. Loculated collections of fluid or air may often require variations in technique that will not be discussed in this chapter.

Adequate analgesia is key to successful, uncomplicated tube thoracostomy. Create a 2- to 3-cm skin wheal with 0.5% to 1.0% lidocaine about one interspace width below the planned thoracic entrance site. Subsequent or serial injections of lidocaine (5 mg/kg maximum dose), including the rib periosteum, intercostal muscles, and chest wall pleura, will greatly improve the ease of the procedure and patient comfort.

Prepare the skin widely and drape the area. For most purposes, chest tube insertion at the sixth interspace is adequate and safe. To prevent pneumothorax at the time of tube removal, plan to make the skin incision a full interspace lower than where you intend to enter the chest. In this way, the tube will pass through a subcutaneous tunnel measuring 2 to 3 cm in length between the skin and the entry site between the ribs. Thus the skin incision should be made at the seventh interspace.

Incise the skin with the scalpel and then create the subcutaneous tunnel with a long curved clamp. Repetitive, gentle spreading to a width equal to your finger and the chest tube will allow adequate access. Identify the top of the rib with the clamp and spread the intercostal muscle just over it, carefully hugging the superior surface. Control the clamp carefully so that when you “pop” through the pleura, the tip of the clamp does not injure underlying tissue. While the clamp is still in, spread the

tips to widen the intercostal defect. Place your index finger through this incision into the chest and “sweep” down any adhesions, feeling for rind on the lung, pleural implants, and blood clots. Confirm the intrathoracic placement of a low chest tube by palpating the superior surface of the diaphragm.

tips to widen the intercostal defect. Place your index finger through this incision into the chest and “sweep” down any adhesions, feeling for rind on the lung, pleural implants, and blood clots. Confirm the intrathoracic placement of a low chest tube by palpating the superior surface of the diaphragm.

Grasp the tip of the chest tube with the tip of a curved clamp and introduce it into the chest as shown (Fig. 24.1A). Inset the tube just far enough so that the last drainage hole is well within the chest cavity. An alternative method is to leave your finger in the tunnel and feed the tube next to it. The fingertip is blunt and allows the tube to be directed in a more specific direction. Either way, spinning the tube in a counterclockwise direction while advancing will help keep the tube from kinking and being misplaced into a fissure.

Secure the tube at the skin level with a heavy silk suture. The suture should be a U stitch or a single horizontal mattress stitch, which will allow skin approximation at the time of closure (Fig. 24.1B). Connect it to a chest drainage and suction device, such as a Pleurovac. Dress the site appropriately.

Removal of the tube is best accomplished by two people. Prepare an occlusive dressing by placing a petroleum jelly gauze on 4 × 4s. Expose the chest tube site and mobilize the stitch. Ask the patient to hold his or her breath in full inspiration. Place the dressing over the site with petroleum jelly apposing the incision. Quickly withdraw the tube, secure the suture, and tape the dressing tightly down while holding it firmly to the chest wall.

Anatomic Points

One of the potential hazards of tube thoracostomy—inadvertent placement of the tube below the diaphragm—can be avoided by analyzing the structure and morphology of the diaphragm. This muscle has a circumferential origin and divides the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. Posteriorly, the diaphragm takes its origin from the anterolateral surfaces of the upper two or three lumbar vertebrae. It has a costal origin from the internal surfaces of the lower six ribs and costal cartilages at the costal margin; hence, as one progresses anteriorly, the origin of the diaphragm becomes progressively more cranial. Anteriorly, it has two small slips of origin from the deep surface of the xiphoid process. From this origin, the muscular fibers insert on the expansive, aponeurotic central tendon.

The upper limits of the diaphragm are at the level of the nipple, or fourth intercostal space, so that it is dome shaped. As a consequence, the peripheral part of the thoracic cavity becomes progressively attenuated inferiorly, resulting in a sharp, narrow costophrenic recess. In the midclavicular line, the reflection of parietal pleura from body wall to diaphragm is at the level of the eighth rib, whereas in the midaxillary line, this reflection is at the level of the tenth rib. Because of this reflection and the dome shape of the diaphragm, incisions below the level of the eighth rib may not enter the pleural cavity and can easily pass through the diaphragm into the abdominal cavity. The sharp costophrenic recess is precisely why excellent clamp control when popping into the chest is mandatory. Overly aggressive entry can easily continue on through the adjacent diaphragm and into the abdomen. The slippery dome has been known to be confused with the diaphragm. Digitally palpating the diaphragm and lung wall helps confirm accurate location.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree