Truncal Vagotomy and Pyloroplasty and Highly Selective Vagotomy

Vagotomy is (rarely) performed to decrease the stimulus to acid output by the parietal cells. Most peptic ulcers respond to eradication of Helicobacter species and acid-/suppressive medication. The remaining role of vagotomy in the current era of excellent medical management is still being clarified.

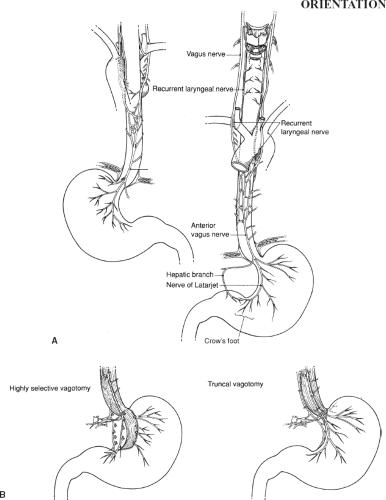

The anatomy of the left and right vagus nerves is shown in Figure 65.1A. Three types of vagotomy have been described: Truncal vagotomy, selective vagotomy, and highly selective (or parietal cell) vagotomy (Fig. 65.1B).

Truncal vagotomy is a total abdominal vagotomy in which both vagal trunks are divided at the esophageal hiatus. The procedure can be performed through the chest (transthoracic vagotomy), which is occasionally done when recurrent ulceration follows gastrectomy and it is known with certainty that a complete vagotomy was not done at the time of the original operation.

Selective vagotomy is a total gastric vagotomy, with preservation of the hepatic branch (innervating the biliary tract) and the celiac branch (innervating the small intestine). Highly selective (or parietal cell) vagotomy divides only the fibers to the parietal cells of the stomach, preserving innervation to the gastric antrum.

Because truncal vagotomy and selective vagotomy denervate the antrum, a drainage procedure, such as pyloroplasty, must be performed. No drainage procedure is needed after highly selective vagotomy because antral innervation is preserved.

In this chapter, truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty (including a brief section on management of the bleeding duodenal ulcer), as well as highly selective vagotomy, are presented. References describing the less commonly performed selective vagotomy, transthoracic vagotomy, and laparoscopic techniques for vagotomy are listed at the end. Although these procedures are, indeed, rarely performed, their occasional use and the manner in which they illustrate regional anatomy have led to their inclusion in this chapter.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified truncal vagotomy and drainage as an “ESSENTIAL UNCOMMON” procedure, and proximal gastric vagotomy (highly selective vagotomy) as a “COMPLEX” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Truncal Vagotomy

Upper midline incision, indwelling nasogastric tube

Retract left lobe of liver cephalad to expose hiatus

Incise peritoneum over esophageal hiatus

Mobilize distal esophagus and encircle it with a Penrose drain

Feel for vagal trunks, clip and divide

Obtain frozen section confirmation

Pyloroplasty

Heineke–Mikulicz

Place two stay sutures on pylorus to elevate anterior wall

Longitudinal incision beginning on distal antrum and crossing pylorus, extending onto duodenum

Close pyloroplasty transversely

Finney

Lembert sutures to anastomose distal antrum to proximal duodenum

Incision from distal antrum through pylorus down onto proximal duodenum

Complete a two-layer anastomosis to close this large opening

Jaboulay

Lembert sutures to anastomose distal antrum to proximal duodenum

Two incisions: One on antrum and one on duodenum

Two-layer anastomosis to close the opening

Approach to bleeding duodenal ulcer

Stay sutures on pylorus, generous longitudinal incision across pylorus

Identify site of bleeding

Secure with three-point suture to secure gastroduodenal artery and all branches

Close pyloroplasty (either as a Heineke–Mikulicz or Finney, depending upon length)

Highly selective vagotomy

Midline incision and mobilize esophagus as above, retract to the right

Mobilize and encircle anterior and posterior vagus trunks with Silastic loops, retract to the left

Seek crow’s foot at distal antrum

Preserving the terminal three divisions of the crow’s foot, begin dissection 5 to 7 cm above pylorus

Sequentially clamp and tie all branches from vagal trunks to stomach (generally this will require several passes)

At the esophagus, continue upward until distal esophagus is skeletonized for 10 cm

Imbricate raw area of lesser curvature with interrupted Lembert sutures

Close abdomen in usual fashion without drains

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Incomplete vagotomy

Injury to esophagus

Injury to spleen

Recurrent hemorrhage (missed bleeder)

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Esophagus

Esophageal hiatus

Left lobe of liver

Left triangular ligament

Diaphragm

Inferior phrenic artery and vein

Stomach

Lesser curvature

Pylorus

Greater curvature

Vagus Nerves

Anterior esophageal plexus

Hepatic division

Anterior nerve of Latarjet

Posterior Esophageal Plexus

Celiac division

Posterior nerve of Latarjet

“Criminal nerve” of Grassi

Truncal Vagotomy and Pyloroplasty

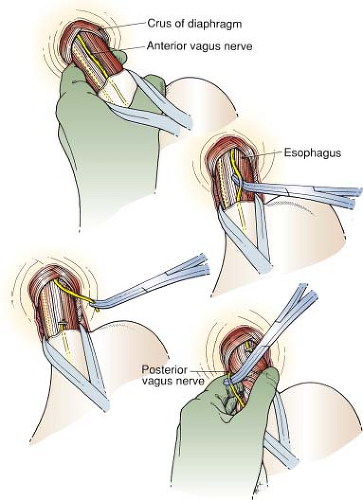

Vagotomy (Fig. 65.2)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine on the operating table. Make an upper midline incision. An indwelling nasogastric tube is important to facilitate identification of the esophagus and its mobilization.

Expose the esophageal hiatus and mobilize the esophagus (see Figures 51.1 and 51.2), encircling it with a Penrose drain. Place the fingers of your nondominant hand behind the esophagus and elevate it, maintaining gentle traction on it.

The main vagal trunks feel like banjo strings. One large trunk lies on the left anterior surface and a slightly smaller one lies to the right and posterior. The anterior vagal trunk is often visible on the surface of the esophagus. Because it is easiest to find, it is generally taken first. Pass a right-angled clamp under the vagal trunk and mobilize it for a total length of 1.5 to 2 cm. Clamp the vagal trunk in the middle of the mobilized segment and place a medium hemoclip at the lower end of the trunk. Cut just above the clip. Lift up on the right-angled clamp to pull the mobilized segment away from the esophagus and clip this segment at the upper end; then cut below, excising a short segment of nerve.

Next, identify the posterior vagal trunk. It is often palpable when gentle tension is placed on the esophagus and the back of the esophagus is felt. Roll the esophagus and posterior vagal trunk one way or the other to bring the vagal trunk into view. If you cannot feel the vagal trunk, search the posterior tissue between the esophagus and the aorta. This nerve is frequently left behind when the esophagus is mobilized and encircled by the Penrose drain at the beginning of the dissection.

Vagal tissue cuts with a very distinct crunching sensation that can be distinguished, with practice, from the minimal sensation felt when cutting small blood vessels or muscle fibers. Nevertheless, submit the vagal fibers for frozen-section confirmation; two good segments of peripheral nerve should be obtained.

Search for other fibers. Carefully feel the entire esophagus, rolling it between your fingers. Divide any suspicious bands running longitudinally on the esophagus.

Check the area for hemostasis and place a moist laparotomy pad there while commencing the drainage procedure. Do not wait for frozen-section confirmation; if two trunks are not

identified on frozen-section analysis, return to the esophageal hiatus after completing the drainage procedure.

identified on frozen-section analysis, return to the esophageal hiatus after completing the drainage procedure.

Anatomic Points

The left lobe of the liver initially obscures visualization of this region. To mobilize the left lobe, cut the left triangular ligament. This ligament attaches the liver to the abdominal side of the diaphragm. Divide it close to the liver (to avoid injury to the inferior phrenic vessels) and between clamps because the ligament can contain bile duct radicals, vessels, and nerves. Divide the peritoneum at the esophageal hiatus with care because the left inferior phrenic vessels can pass immediately anterior to the esophageal hiatus.

When exposure is adequate, one will begin to see certain structures passing through the hiatus—namely, the esophagus, various arrangements of the vagal nerve trunks, and esophageal veins and arteries. The left and right vagus nerves form the anterior and posterior esophageal plexuses in the upper to middle thorax. Each plexus is predominantly derived from the left or right vagus nerve. However, each receives contributions from its contralateral counterpart. Differential growth of the greater curvature of the stomach during development causes an apparent rotation. The left vagus nerve comes anterior and becomes the anterior vagal trunk, whereas the right vagus nerve becomes the posterior vagal trunk. Distally, both anterior and posterior esophageal plexuses typically reunite above the esophageal hiatus to form anterior (predominantly left vagus) and posterior (predominantly right vagus) trunks. Thus, in about 90% of cases, only two vagal structures pass through the hiatus. Typically, both of these structures are to the right of the esophageal midline. The anterior trunk should be located on the anterior surface of the esophagus. The posterior vagus is typically closer to the right margin of the esophagus than is the anterior trunk. It can be located as much as 2 cm from the esophagus and spatially is closer to the aorta than to the esophagus.

Soon after passing through the hiatus, the anterior vagal trunk divides into a hepatic division, which runs to the porta hepatis in the gastrohepatic ligament, and a principal anterior nerve of the lesser curvature of the stomach (anterior nerve of Latarjet), which accompanies the left gastric artery and gives off branches to the anterior stomach. Similarly, the posterior vagal trunk divides into a large celiac division, which accompanies the proximal left gastric artery to the celiac ganglion, and a principal posterior nerve of the lesser curvature of the stomach (posterior nerve of Latarjet), which gives off branches to the posterior stomach.

Variations in the number of vagal structures passing through the esophageal hiatus occur in about 10% of cases and depend on the distal extent of the esophageal plexuses. If the plexus terminates at a point more proximal than usual, the trunks can divide in the esophageal hiatus, so that four vagal structures can pass through the hiatus. More than four vagal structures may pass through the hiatus if additional gastric branches pass through independently, or if the esophageal plexuses extend into the abdomen and then later form the two principal trunks. Fortunately, variations involving the posterior vagal trunk are less common than those of the anterior trunk. However, because it is more difficult to visualize the posterior vagal elements than the anterior ones, a posterior gastric branch is probably more likely to be missed. The notorious “criminal nerve” of Grassi refers to the most proximal posterior gastric branch that arises at, or above, the celiac division.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree