Rapid development of tolerance to their therapeutic effects

High risk of dependence

Significant withdrawal effects

Serious adverse effects

Lethality in overdose

BZD-treated patients, their families, and their physicians now wonder whether a person should be considered an abuser after taking these drugs for longer than a few weeks. Several reviews, however, generally support the conclusion that even long-term therapeutic use is rarely accompanied by inappropriate drug-taking or drug-seeking behavior (e.g., high and sustained dose escalation; trying to obtain the drug from several physicians or illicitly; 5,6,7,8,9 and 10). A decade ago an international group of experts considered the therapeutic dose, potential for dependence, and abuse liability of BZDs in the long-term treatment of anxiety disorders. They concluded that although the BZDs pose a higher risk of dependence than most potential substitutes, they pose a lower risk of dependence than older sedatives and recognized drugs of abuse (11).

TABLE 12-1 ANTIANXIETY AGENTS Usual Daily Dosage (mg/d) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Do not drink more than social amounts of alcohol

Do not have a history of dependence on other drugs

Do not abuse BZDs

Do not take more than the prescribed dose

Usually attempt to reduce dose to avoid addiction

Are able to successfully withdraw from BZDs without resorting to another dependenceinducing drug (Table 12-2)

neurotransmitter system in the brain, which acts in the following locations:

Stellate inhibitory interneurons in the cortex

Striatal afferents to globus pallidus and substantia nigra

Purkinje cells in the cerebellum

TABLE 12-2 MEDICAL VERSUS NONMEDICAL USERS AND/OR ABUSERS OF BENZODIAZEPINES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 12-3 PHARMACODYNAMICS OF ANXIOLYTICS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Partial or full agonists (e.g., diazepam), which are anxiolytic and anticonvulsant

Partial or full inverse agonists (e.g., FG 7142), which are anxiogenic and proconvulsant

Antagonists (e.g., flumazenil), which are neutral

1,4-BZDs—contain nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 4 in the diazepine ring; this grouping accounts for most therapeutically important agents (e.g., bromazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, flunitrazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, lormetazepam, midazolam, nitrazepam, oxazepam, prazepam, quazepam, temazepam)

1,5-BZDs—contain nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 5 in the diazepine ring (e.g., clobazam)

Tricyclic BZDs—often consist of the 1,4-BZD nucleus with an additional ring fused at positions 1 and 2 (e.g., alprazolam, adinazolam, loprazolam, triazolam)

Autonomic nervous system (ANS)

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis

Potency

Onset and duration of clinical activity

Type and frequency of adverse effects after both single and multiple doses

Withdrawal phenomena

TABLE 12-4 BENZODIAZEPINE DIFFERENCES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

slower absorption. BZDs given orally differ in their speed of absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. For example, absorption time is 0.5 hours for clorazepate, 1 hour for diazepam, 1.3 hours for triazolam, 2 hours each for alprazolam and lorazepam, 2 to 3 hours for oxazepam, and 3.6 hours for flurazepam. Absorption, however, may be influenced by the presence or absence of food in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, patients who take a BZD SH with a bedtime snack may experience a slower onset of hypnotic activity than if the same drug were taken several hours after a meal.

Those biotransformed by oxidative metabolism in the liver, primarily N-demethylation or hydrox ylation (e.g., adinazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, diazepam), often yield pharmacolog ically active metabolites that must undergo fur ther metabolic steps before excretion

Unlike oxidized BZDs, conjugated BZDs (e.g., lorazepam, lormetazepam, oxazepam) do not have active metabolites and only the parent compounds account for clinical activity

BZD SHs that undergo a high first-pass effect before reaching the systemic circulation (e.g., midazolam and triazolam) may have short-lived but active metabolites

TABLE 12-5 METABOLISM OF BENZODIAZEPINE ANXIOLYTICS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ultrashort-acting (less than 5 hours), such as midazolam and triazolam

Short-to-intermediate acting (6 to 12 hours), such as oxazepam, bromazepam, lorazepam, loprazolam, temazepam, estazolam, lormetazepam, and alprazolam

Long-acting (more than 12 hours), such as flunitrazepam, clobazam, flurazepam, clo razepate, ketazolam, chlordiazepoxide, and diazepam

distribution. During multiple dosing, however, BZDs with longer half-lives accumulate slowly and after termination of treatment disappear slowly, whereas BZDs with short half-lives have minimal accumulation and disappear rapidly when treatment stops.

Acute, severe anxiety

Precipitating stresses

Low level of depression or interpersonal problems

No previous treatment, or a good response to earlier treatment

Expectation of recovery

Desire to use medication

Awareness that symptoms are psychological

Some improvement in the first treatment week

severe suffering and handicap an otherwise healthy person. Because these disorders are chronic, long-term treatment is often required to achieve optimal benefit. Even when long-term BZD therapy is appropriate, however, periodic reassessment of its efficacy, safety, and necessity is good medical practice. In this context, existing data indicate

Long-term users account for the bulk of anxiolytic and hypnotic BZDs sold in the United States

About 80% of SHs sold are consumed by individuals reporting daily use of 4 months or longer

The number of long-term users of anxiolytic and hypnotic agents has increased, even though its benefit is not established (33)

Excessive daytime drowsiness

Cognitive impairment and confusion

Psychomotor impairment and a risk of falls

Paradoxical reactions and depression

Intoxication, even on therapeutic dosages

Amnestic syndromes

Respiratory problems

Abuse and dependence

Breakthrough withdrawal reactions

Undertreatment

Partial responsiveness that would worsen without treatment

Presence of symptoms more responsive to a different class of drug (e.g., an antidepressant)

Development of some degree of tolerance to the anxiolytic effect

Development of a chronic state of withdrawal

gastroenterological or neurological investigations for which various treatments were ineffective. Ashton notes that it is arguable whether these patients would have developed their symptoms without BZD treatment; however, they

Were not present prior to initiation of the BZD

Were not amenable to other treatments during BZD use

Largely disappeared when the BZD was discontinued

Regular treatment monitoring

Use of the lowest possible doses compatible with achieving the desired therapeutic effect

Use of intermittent and flexible dosing schedules rather than a fixed regimen

Gradual dose reduction

Can alleviate both anxiety and depression, which commonly co-occur (49)

Pose minimal risks for dependence and withdrawal symptoms compared to BZDs, particularly with long-term treatment

Have a different adverse effect profile than BZDs, which may be more tolerable for certain patients

generation of antidepressants was effective in a range of anxiety disorders, including GAD. For example, venlafaxine extended-release formulation (XR) was efficacious in GAD outpatients without associated major depression. These data came from clinical trials conducted by expert clinical psychopharmacologists with broad experience in the assessment of psychotropic medications for anxiety disorders. The first of these trials (51) compared the efficacy of venlafaxine XR with buspirone. The second trial (52) also supported the efficacy of venlafaxine XR in nondepressed outpatients with GAD, and a third trial replicated these findings in a primary care setting (53). Two more recent controlled trials also supported the effectiveness of this agent for the treatment of GAD in children and adolescents (54; see Chapter 14).

feeling and find that it interferes with various activities, such as problem solving, driving, and overall work function.

TABLE 12-6 BUSPIRONE VERSUS PLACEBO OR BENZODIAZEPINE FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

It is only useful when taken regularly for several weeks because it has no immediate effect after a single tablet and is not helpful in treating an acute episode; many patients who have taken BZDs expect relief after a single tablet, but buspirone cannot be used on an as needed basis

It may have diminished efficacy in the long-term treatment of anxiety

It was not effective for panic attacks in several small studies

It does not block BZD withdrawal symptoms; often a critical consideration because many patients previously have been on or are presently taking a BZD

problems with BZD withdrawal symptoms. Increased antianxiety effects are observed in some patients treated concurrently with low doses of buspirone and a BZD. Further, buspirone may be indicated in individuals with GAD and a history of chemical dependency who have failed or who could not tolerate antidepressants (93).

TABLE 12-7 CLINICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BUSPIRONE AND THE BENZODIAZEPINES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

received 2 mg twice daily of tiagabine to a maximum of 8mg twice daily, and 20 subjects received paroxetine (20 to 60 mg/day), which served as a positive control (104). Subjects were assessed using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the SDS. The mean tiagabine dose was approximately 10 mg per day (range, 4to 16 mg/day), and the mean paroxetine dose was 27 mg per day (range, 20 to 40 mg/day). Significant improvement in both anxiety and comorbid depressive symptoms was observed with both agents. Sleep quality and daytime functioning also improved.

It may be an anxiolytic

The development of tolerance and withdrawal would be unlikely at therapeutic doses

It may work through inhibition of sodium or calcium channels, having an antiglutaminergic effect

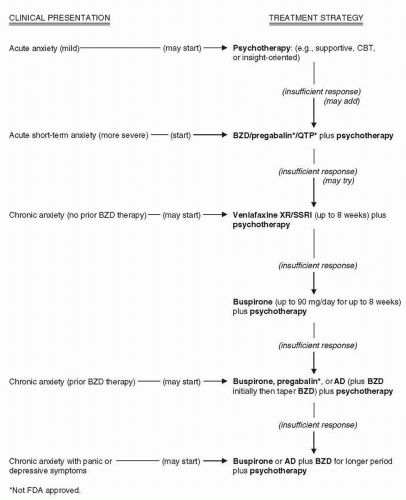

Nonpharmacological interventions (i.e., various psychotherapies)

Antidepressants

Azapirones (e.g., buspirone)

β-Blockers or antihistamines in selected cases

Anticonvulsants (e.g., pregabalin)

Second-generation antipsychotics (e.g., queti-apine XR)

Nutraceuticals (e.g., kava)

Places or situations from which one cannot readily escape

A specific feared object or situation (e.g., heights)

Certain types of social or performance situations

Generalized (i.e., fear of most social situations) which represents about 67% of those affected and is associated with greater impairment, chronicity, and comorbidity

Nongeneralized (i.e., fear of a limited number of specific situations, such as dating)

Marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations

Fear of being embarrassed or humiliated

Such situations are avoided or endured with distress or anxiety

Symptoms interfere with social, occupational, and/or academic activities

Recognition that fear is excessive or unreasonable

Amygdala overactivity (136)

A decreased left hemispheric advantage for word or syllable processing (138)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree