Overview

An 83-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gastroesophageal reflux disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with sick sinus syndrome was admitted to the cardiology service of a teaching hospital for initiation of an antiarrhythmic medication and placement of a permanent pacemaker.

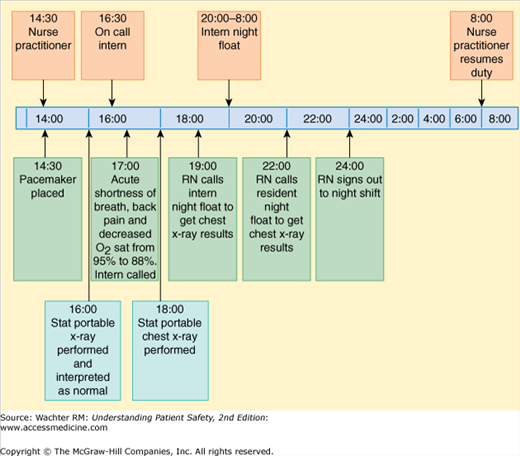

The patient underwent pacemaker placement via the left subclavian vein at 2:30 pm. A routine postoperative single-view radiograph was taken and showed no pneumothorax. The patient was sent to the recovery unit for overnight monitoring. At 5:00 pm, the patient stated he was short of breath and requested his COPD inhaler. He also complained of new left-sided back pain. The nurse found that his oxygenation had dropped from 95% to 88%. Supplemental oxygen was started and the nurse asked the covering physician to see the patient. The patient was on the nurse practitioner (NP)-run non-house staff service; however, the on-call intern provides coverage for patients after the NPs leave for the day.

The intern, who had never met the patient before, examined him and found him already feeling better and with improved oxygenation after receiving the supplemental oxygen. The nurse suggested a stat x-ray be done in light of the recent surgery. The intern concurred and the portable x-ray was completed within 30 minutes. About an hour later, the nurse wondered about the x-ray and asked the covering intern if he had seen it. The intern stated that he was signing out the x-ray to the night float resident, who was coming on duty at 8:00 pm.

Meanwhile, the patient continued to feel well except for mild back pain. The nurse gave him analgesics and continued to monitor his heart rate and respirations. At 10:00 pm, the nurse still hadn’t heard anything about the x-ray, so she called the night float resident. The night float had been busy with an emergency but promised to look at the x-ray and advise the nurse if there was any problem. Finally at midnight, the evening nurse signed out to the night shift nurse, mentioning the patient’s symptoms and noting that the night float intern had not called with any bad news.

The next morning, the radiologist read the x-ray performed at 6:00 pm and notified the NP that it showed a large left pneumothorax. A chest tube was placed at 2:30 pm, nearly a full day after the x-ray was performed. Luckily, the patient suffered no long-lasting harm from the delay.1

Some Basic Concepts and Terms

In a perfect world, patients would stay in one place and be cared for by a single set of doctors and nurses. But, come to think of it, who would want such a world? Patients get sick, and then get better. Doctors and nurses work shifts, and then go home. Residents graduate from their programs and enter practice. So handoffs—the process of transferring primary authority and responsibility for clinical care from one departing caregiver to another incoming one2—and transitions are facts of medical life.

As we all learned when we played the game of “telephone” as kids, every handoff and transition comes with the potential for a “voltage drop” in information. (It also carries the possibility that a new set of eyes or circumstances will lead to a clinical benefit, but our purpose here is not to explore that optimistic scenario.) In fact, handoff and transitional errors are among the most common and consequential errors in healthcare. Despite this, these mistakes received little attention until recently, in part because, by their very nature, they tend to fall between the cracks of professional silos. As we have come to recognize the frequency and impact of handoff and transition errors, we are beginning to learn how to mitigate the harm that often accompanies them.

Healthcare is chock-full of two kinds of transitions and handoffs.3 The first are patient related, as a patient moves from place to place within the healthcare system, either within the same building or from one location to another (Table 8-1). The second are provider related, which occur even when patients are stationary (Table 8-2).

|

|

Both kinds of handoffs are fraught with hazards. For example, one study found that 12% of patients experienced preventable adverse events after hospital discharge, most commonly medication errors (Chapter 4).4 Part of the problem is that nearly half of all discharged patients have test results that are pending at discharge, and many of them (more than half in one study) fall through the cracks.5 In another study, researchers found that being covered, principally at night, by a different physician was a far better predictor of hospital complications and errors than was the severity of the patient’s illness.6 The same researchers devised a standardized computerized sign-out form and the error rate fell by a factor of 3.7

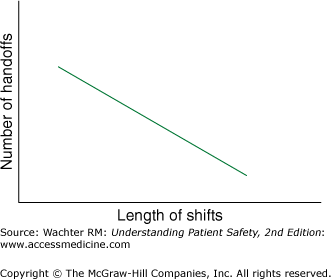

Even if we grant that some transitions are necessary, one might reasonably ask whether healthcare needs to have quite so many of them. The answer is probably yes. Research has demonstrated that patients do worse when nurses work shifts longer than 12 hours, and that intensive care unit (ICU) residents make fewer errors when they work shifts averaging 16 hours instead of the traditional 30–36 hours (Chapter 16).8,9 Unfortunately, in a 24/7 hospital, implementing these shift limits automatically generates handoffs (Figure 8-1), such as many of the ones in this case (Figure 8-2). Other handoffs emerge when patients receive appropriately specialized care.

Although some might wistfully long for the day when the family doctor saw the patient in the office, the emergency room, the hospital, and the operating and delivery room, most patients now prefer the additional expertise, training, and availability of specialists in sites of care (i.e., emergency department, ICU, and, increasingly, the hospital10), procedures (delivering a baby), or diseases (heart attack or stroke). As these specialists become involved in a patient’s care, they create transitions and the need for accurate information transfer. So too does a patient’s clinical need to escalate the level of care (such as transitioning from hospital floor to step-down unit) or the economic realities that often drive de-escalation (hospital to skilled nursing facility).

The presence of all these handoffs and transitions makes it critical to consider how information is passed between providers and places. Catalyzed in part by the mandated reduction in resident work hours in the United States that began in 2003 (Chapter 16), there has been far more attention paid to handoffs in recent years. In my own hospital, for example, the number of handoffs by internal medicine residents rose by 40% after duty-hours limits were implemented.11

There is increased pressure coming from the policy arena as well. In 2006, the Joint Commission issued National Patient Safety Goal 2E (Appendix IV), which required healthcare organizations to “implement a standardized approach to handoff communications including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions.” Spurred on by studies demonstrating staggeringly high 30-day readmission rates in Medicare patients (20% overall, nearly 30% in patients with heart failure),12 in 2012 Medicare began penalizing hospitals with high readmission rates.13 All of this attention has catalyzed research on handoffs and transitions, giving us a deeper understanding of best practices, which have both structural and interpersonal components.

This chapter will provide a general overview of best practices for person-to-person handoffs and patient transitions, and then focus on one particularly risky transition: hospital discharge. Additional information about handoffs and transitions can be found in the discussion of medication reconciliation (Chapter 4), information technology tools (Chapter 13), and resident duty hours (Chapter 16).

Best Practices for Person‐to-Person Handoffs

Like many other areas of patient safety, the search for best practices in handoffs has led us to examine how other industries and organizations move information around. This search has revealed several elements of effective handoffs: an information system, a predictable and standardized structure, and robust interpersonal communication. In one particularly memorable example, physicians at London’s Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital studied Formula 1 motor racing, particularly the pit-stop crews (who switch out a car’s tires, gas up the car, clean the vents, and send the car screeching back onto the track—all in seven seconds), for lessons in how to do effective handoffs.14 The differences in the approaches of the pit-stop crews and the surgical teams were striking. Inspired, Great Ormond hired a human factors expert (Chapter 7) and reengineered the way its teams performed their postoperative handoffs (Table 8-3). The new model resulted in a significant decrease in handoff errors.15,16

| Safety Theme | Practice | Establishment of Handover Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Formula 1: the “lollipop” man coordinates the pit stop. Aviation: the captain has command and responsibility | Old: unclear who was in charge. New: anesthetist given overall responsibility for coordinating team, transferred to the intensivist at the end of the handover |

| Task sequence | Formula 1 and aviation: there is a clear rhythm and order to events | Old: inconsistent and nonsequential. New: three phases defined: (1) equipment and technology handover; (2) information handover; (3) discussion and plan |

| Task allocation | Formula 1: each team member has only one to two clearly defined tasks. Aviation: explicit acknowledged allocation of tasks for emergencies | Old: informal and erratic. New: people allocated tasks: ventilation—anesthetist; monitoring—operating room assistant; drains—nurses. The anesthetist identified and handed information over to the key receiving people |

| Predicting and planning | Formula 1: failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) used to break down pit stops into individual tasks and risks. Aviation: pilots are trained to anticipate the expected, and to plan contingencies | Old: risks identified informally and often not acted upon. New: a modified FMEA was conducted and senior representatives commented on highest areas of risk. Safety checks were introduced, and the need for a ventilation transfer sheet was identified |

| Discipline and composure | Formula 1: very little verbal communication during a pit stop. Aviation: explicit communication strategies used to ensure a calm and organized atmosphere | Old: ad hoc and unstructured, with several simultaneous discussions in different areas of the ICU and theaters. New: communication limited to the essential during equipment handover. During information handover, the anesthetist and then the surgeon speak alone and uninterrupted, followed by discussion and agreement of the recovery plan |

| Checklists | Formula 1 and aviation: a well-established culture of using checklists | Old: none. New: a checklist was defined and used as the admission note by the receiving team |

| Involvement | Aviation: crew members of all levels are encouraged and trained to speak up | Old: communications primarily within levels (e.g., consultant to consultant or junior to junior). New: all team members and grades encouraged to speak up. Built into discussions in phase 3 |

| Briefing | Formula 1 and aviation: well-established cultures of briefing even on race day, and before every flight | Old and new (process already in place): planning begins in a regular multidisciplinary meeting, reconfirmed the week before surgery, with further problems highlighted on the day |

| Situation awareness | Formula 1: the “lollipop man” has overall situation awareness at pit stops. Aviation: pilots are trained for situation awareness. In difficult circumstances the senior pilot manages the wider aspects of the flight while the other pilot controls the aircraft | Old: not previously identified as being important. New: the consultant anesthetist and intensivist have responsibility for situation awareness at handover, and regularly stand back to make safety checks |

| Training | Formula 1: a fanatical approach to training and repetition of the pit stop. Aviation: training and assessment are regularly conducted in high-fidelity simulators | Old: no training existed. New: a high turnover of staff requires an alternative approach. The protocol could be learned in 30 minutes. Formal training introduced; laminated training sheets detailing the process are provided at each bedside |

| Review meetings | Formula 1: regular team meetings to review events. Aviation: crew are encouraged to debrief after every flight | Old and new (already in place): a weekly well-attended clinical governance meeting, where problems/solutions openly discussed |

The Joint Commission’s expectations, expressed in its 2006 National Patient Safety Goal, include interactive communications, up-to-date and accurate information, limited interruptions, a process for verification, and an opportunity to review any relevant historical data. Vidyarthi and colleagues developed the mnemonic “ANTICipate” to help structure written sign-outs (Table 8-4). For example, in the case that began the chapter, listing “Tasks” in the form of “if, then” statements might have decreased the ambiguity. The written sign-out might have included: “Check the chest x-ray taken at 6 pm. If clear, call the nurse. If it shows a pneumothorax, call thoracic surgery for possible chest tube.” Contingency plans could have taken the form of: “if the patient is short of breath, try an albuterol inhaler (history of COPD), but also consider pneumothorax (patient had recent line placement).”1

| Administrative | Accurate information, such as name and location |

| New information | A clinical update, including brief history and diagnosis, updated medication and problem list, current baseline status, and recent procedures and significant events |

| Tasks | The “to do” list, best expressed in “if/then” statements |

| Illness | The primary provider’s assessment of the patient’s severity of illness |

| Contingency plans | Statements that assist in cross-coverage, including things that have and have not worked in the past |

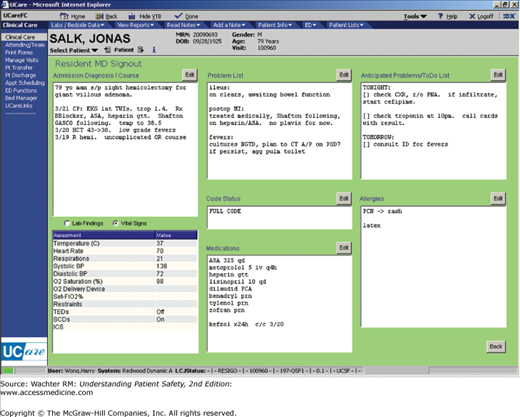

While written sign-outs can take a variety of forms, there is an increasing recognition of the advantages of computerized sign-out systems over traditional index cards. At the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, we developed a computerized sign-out module (“Synopsis”), which resides within the electronic medical record (Figure 8-3). The template standardizes the content of the sign-out and allows multiple providers to see the same data. It also imports certain information from the remainder of the electronic medical record (including administrative information, vital signs, laboratory studies, medication lists, and resuscitation [“code”] status), while allowing for free-text data entry. As one might expect, systems like this improve the quality of sign-outs and decrease the risk of communication-related errors.7,17,18