Tracheostomy and Cricothyroidotomy

Grant O. Lee

Kent Choi

Tracheostomy is necessary when long-term access to the airway for ventilatory support or respiratory toilet is required. It may also be indicated during emergency situation when surgical airway is needed. This chapter describes open tracheostomy and open cricothyroidotomy; percutaneous tracheostomy (Chapter 4) is an alternative in selected patients. Open tracheostomy is best performed in a controlled setting with a fully equipped operating room where adequate lighting, electrocautery, suction, and airway control. Percutaneous tracheostomy may be performed at the bedside, generally in the intensive care unit, but requires the same attention to airway control as formal tracheostomy (see Chapter 4).

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified Tracheostomy as an “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedure.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified Cricothyro/dotomy as an “ESSENTIAL UNCOMMON” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE (TRACHEOSTOMY)

Position patient, check equipment, test balloon of tracheostomy tube

Identify five midline landmarks

Transverse or vertical incision at midline, one finger breadth above the suprasterna notch

Divide tissues in midline

Retract or divide thyroid isthmus

Expose trachea and count rings down from cricoid

Incision between second and third ring

Pull back endotracheal tube slowly until it is just above the tracheal opening

Spread incision and insert tube

Confirm position of tube by passage of suction catheter; secure tube

STEPS IN PROCEDURE (CRICOTHYROIDOTOMY)

Position patient, check equipment, check balloon of tracheostomy tube

Transverse incision over cricothyroid membrane

Control bleeding by manual pressure

Stab into membrane

Spread and insert tube, secure tube, pack wound to control bleeding

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Supraglottic tracheostomy

Tracheoinnominate arterial fistula (delayed complication)

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Larynx

Thyroid cartilage

Cricoid cartilage

Median cricothyroid ligament

Cricothyroid artery

Trachea

Landmarks

Mental protuberance

Hyoid bone

Laryngeal prominence

Manubrium sterni Jugular (suprasternal) notch

Associated Structures

Thyroid gland Isthmus

Pyramidal lobe

Anterior jugular vein

External jugular vein

Platysma muscle

Brachiocephalic (innominate) trunk

Brachiocephalic (innominate) vein

Jugular venous arch

Brachial plexus

A surgical airway may be required in an emergency when the patient cannot be intubated in the normal fashion (e.g., when massive facial trauma or edema precludes safe intubation). In this situation, cricothyroidotomy (see Fig. 3.8) can be performed more quickly and more safely than formal tracheostomy.

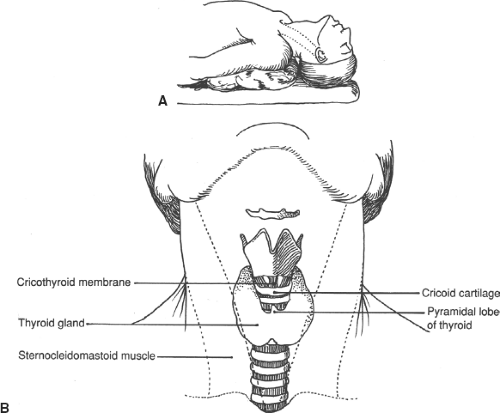

Positioning the Patient (Fig. 3.1)

Technical Points

Slightly hyperextend the neck by placing a small roll under the patient’s shoulders (Fig. 3.1A). Do not hyperextend the neck in a patient with a known or suspected cervical spine injury, because the resulting vertebral motion may cause irreversible damage to the spinal cord.

Select a tracheostomy tube appropriate to the size of the patient; for an average-sized adult, a number 7 or 8 tube will work well. Test the balloon and then deflate and lubricate it with sterile lubricant. Place the obturator inside the tube. Be sure that a soft rubber suction catheter is available on the sterile field for suctioning the tracheostomy after the tube is inserted. Sterilize the skin and drape the patient while allowing access to the endotracheal tube.

Whereas tracheostomy can be performed in infants younger than 1 month of age with acceptable procedure-related morbidity, cricothyroidotomy should be avoided in patients younger than 12 years of age due to increased incidence of subglottic stenosis. Endotracheal intubation over a flexible bronchoscope is the procedure of choice as an alternative.

Anatomic Points

Landmark structures of this region are shown in Fig. 3.1B. The thyroid gland, often with a pyramidal lobe, overlies the trachea. The thyroid cartilage and cricoid cartilage are easily palpable above the thyroid gland. The hyoid bone can be palpated above the thyroid cartilage. The paired sternocleidomastoid muscles are located laterally to it.

The phrenic nerve arises from spinal cord levels C3 to C5 and the brachial plexus is derived from C5 to T1. Spinal cord damage at or above C3 will result in death secondary to paralysis of all respiratory muscles. Damage of the cord at levels involving the brachial plexus can result in quadriplegia. Hyperextension of the neck stretches the cord and may compress the cord against a damaged cervical vertebra; such a maneuver may also result in complete transection as the cord is caught between broken fragments of cervical vertebrae.

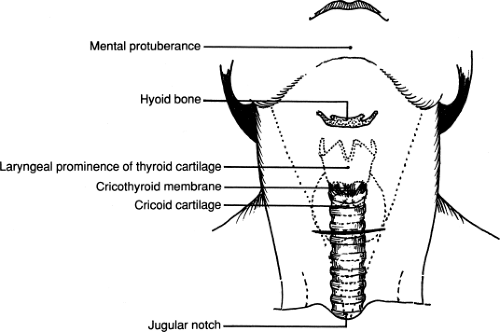

Identification of Landmarks (Fig. 3.2)

Technical and Anatomic Points

Palpate five midline landmarks, including the mental protuberance, or tip of the chin; the body of the hyoid bone; the laryngeal prominence of the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple); the cricoid cartilage; and the suprasternal notch of the manubrium sterni. All of these constant bony or cartilaginous landmarks should be identified with certainty to avoid inadvertent supraglottic incision. Repeated palpation of these readily identifiable

midline structures will help ensure that the dissection remains in the midline.

midline structures will help ensure that the dissection remains in the midline.

Skin Incision for Tracheostomy (Fig. 3.3)

Technical Points

A vertical incision at midline one finger breadth above the suprasternal notch provides the best exposure and is preferred in emergency situations. With this incision, there is less bleeding and less risk for damage to nerves and vessels. The incision shown is slightly larger than usually required. Do not hesitate to make a generous incision if exposure is difficult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree