Towards An Understanding of the Physiology of the Stomach

Gastric fistulae: a unique opportunity

|

William Beaumont and the case of Alexis St. Martin

William Beaumont was born on November 25, 1785, in Lebanon, Connecticut, and began his study of medicine at the age of 22 years. In the War of 1812, he accepted a position in the Army as an acting surgeon’s mate and saw active service. In 1819, after a brief spell in practice, his former colleague, Joseph Lovell, who had now become Surgeon General, offered Beaumont a commission, and he was assigned to Fort Mackinac.

Fort Mackinac was located on the island of Michel Mackinac at the junction of lakes Huron and Michigan. Beaumont was the only physician within 300 miles and was often busy because of frequent brawls among Native Americans and fur traders. On the morning of June 6, 1822, a 19-year-old voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the left upper abdomen and chest. Beaumont was called to see the victim and noted a disastrous wound. He thought the chances of survival were slim and remarked, “The man cannot live 36 hours; I will come and see him by and by.”

Surprisingly, St. Martin survived, and after approximately 10 months, his wound was largely healed, but a gastric fistula remained. During this time, Beaumont had been actively involved in the care of St. Martin. By this stage, St. Martin had become penniless; the county authorities, refusing further support, proposed transporting him 1,500 miles back to his birthplace in Canada. Beaumont opposed the proposal, fearing for the safety of his patient and wishing to study his condition further. In April of 1823, Beaumont moved his patient into his own home, where he remained for almost 2 years under constant care and attention. In 1824, Beaumont had sent his commanding officer (Surgeon General Lovell) a manuscript concerning this patient. It was published in the Medical Recorder as A Case of Wounded Stomach by Joseph Lovell, Surgeon General, U.S.A. The oversight resulting in Beaumont’s omission as an author was soon remedied, and he was instated as a coauthor.

At this stage, Beaumont recognized the unique opportunity that St. Martin’s gastric fistula presented and began his epic investigation into gastric function and digestion. In 1826, his first paper was published, but, unfortunately, further studies were curtailed by his military transfer to Fort Niagara and the disappearance of St. Martin into Canada. It took Beaumont until 1829 to locate St. Martin and arrange a job for him with the American Fur Company. Under the auspices of the company, St. Martin was sent to Fort Crawford on the Upper Mississippi River, where Beaumont was then stationed. During the next 2 years, many experiments were performed, but not long afterward, St. Martin and his family became so homesick and discontented that they returned to Canada.

Studying St. Martin had by now become an obsession for Beaumont, and he attempted to travel to Europe with him for further scientific investigation. Although this proposed trip failed, he was, with the help of Lovell, able to enlist St. Martin in the United States Army to forestall any further episodes of abscondment, which would hence be regarded as desertion. Thereafter, Beaumont entered into a formal written agreement with St. Martin as his “human guinea pig.” In return for allowing the study of his stomach and digestion, St. Martin was to receive board, lodging, and a certain sum of money for the year.

Despite being an unpleasant and dissolute person to work with, St. Martin was studied by Beaumont without further interruption until November 1, 1833. At this stage, he again disappeared into Canada, and Beaumont was

never able again to work with him. St. Martin died at the age of 83 and, in fact, outlived his physician, Beaumont, by several years.

never able again to work with him. St. Martin died at the age of 83 and, in fact, outlived his physician, Beaumont, by several years.

Beaumont studied the physiologic manifestation of digestion and produced a classic text on the subject in 1833. Despite his lack of training as a physiologist and his relatively unsophisticated medical background, Beaumont’s work remained a model on the subject. In essence, by 1833, Beaumont had been able to outline the basic principles of digestion in a human and establish the presence of hydrochloric acid in gastric juice.

Although the studies of a patient with gastric fistula were unique for North America in the nineteenth century, in Europe, similar observations had been made previously. In 1797, Jacob Anton Helm of Vienna studied a 58-year-old woman, Therese Petz of Breitenwaida, who had a spontaneous gastric fistula. Using a hired person, Zyriak Sieddeler, and himself, with his own brother as a control, Helm performed meticulous studies of digestion, intragastric temperature, and salivary function. Helm had no skills in chemistry, and he did not measure acid, nor was he able to demonstrate a change in the color of dye to indicate the presence of acid.

Similarly, in 1801, Rouilly transferred to the care of Dupuytren and Bichat in Paris a patient, Madeline Gore, with a gastric fistula. Gore’s gastric juice was analyzed by Clarion, a professor of chemistry, who performed the first quantitative assessment of gastric juice. Clarion found neither acid nor alkali and concluded that gastric juice was identical to saliva. This conclusion remained dogma in the French medical profession so that, even in 1812, when Montegre reported acid in fasting and mealstimulated gastric juice, he attributed this acid to the digestion of food and saliva.

“Le milieu intérieur”

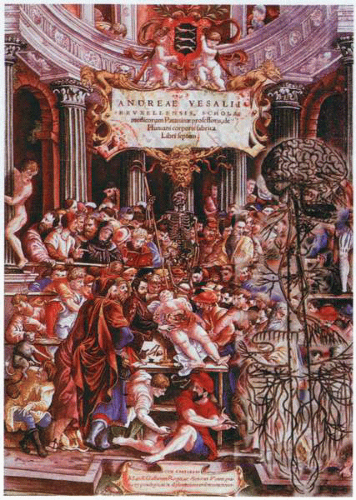

By the sixteenth century, there still existed considerable controversy as to the events that occurred in the lumen of the stomach. A number of reactionary and thoughtful individuals, including Paracelsus, Van Helmont, and Spallanzani, had written effectively about their individual concepts of gastric function. Their ideas ranged from chemical principles of an undefined nature, to archei (spirits), to the presence of acid, as proposed by Spallanzani. Many investigators in numerous countries considered the fundamental problem of digestion at many different levels. Of particular interest was the philosophic approach used by individuals who, although learned, had no formal training in science. Most interesting among these was the gourmand Brillat-Savarin.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826)

The preoccupation of the French with food was never better exemplified than in the life and writings of the gourmet Brillat-Savarin. Indeed, his philosophic observation antedated by many years the concept of the central modulation of gastric secretion.

He worked in Paris for years on a book called The Physiology of Taste, which was finally published in 1825. It consisted of a series of thoughtful essays that detailed his ideas regarding the preparation of food, its role in philosophy and life, and the role of digestion and different foods in behavior. Chapters include discussions of osmazomes, the erotic power of truffles, the nature of digestion, and the dangers of acids. Much of the content of this work reflects Savarin’s interactions with philosophers and physicians of his time. Indeed, guests at his table included Napoleon’s physician Corvisart, the surgeon Dupuytren, the pathologist Cruveilhier, and other great literary and scientific minds of his time. Conversations among these individuals would no doubt have provided Brillat-Savarin with considerable information regarding the chemistry of food and its relationship to the physiology of digestion.

Defining gastric secretion

The question of acid in the stomach had been a vexatious one for many years. Opinions had ranged from there being no acid in the stomach at all to its originating from the pancreas. Physicians of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries felt that any acid present in the stomach was the result of putrefaction or fermentation and did not in any way reflect an active secretory process of the

body or the stomach itself. It was, however, the general opinion of physiologists up to the time of Spallanzani that a free, or at least unsaturated, acid usually existed in the stomach and was necessary for digestion. Indeed, the studies of Edward Stevens in Edinburgh and Lazzaro Spallanzani in Pavia had concluded that the antiseptic powers of gastric juices invalidated the possibility of fermentation as a means of gastric digestion.

body or the stomach itself. It was, however, the general opinion of physiologists up to the time of Spallanzani that a free, or at least unsaturated, acid usually existed in the stomach and was necessary for digestion. Indeed, the studies of Edward Stevens in Edinburgh and Lazzaro Spallanzani in Pavia had concluded that the antiseptic powers of gastric juices invalidated the possibility of fermentation as a means of gastric digestion.

A second controversial issue surrounded what the exact nature of the acid might be. Johann Tholde had first described the acid known as hydrochloric acid, although it had also been called muriatic acid for many years. The detection of this substance in the stomach was first reported by William Prout in 1823. At a meeting of the Royal Society in London on December 11, 1823, in a lucid and elegant discourse, he provided incontrovertible evidence that gastric juice of many different animals (hares, dogs, horses, cats) contained hydrochloric (muriatic) acid. In addition, Prout demonstrated that the same acid was present in dyspeptic patients, and that the amount of this acid appeared to be related to the degree of dyspepsia. Thus, the subject of the exact nature of the acid in gastric juice appeared to be resolved. Unfortunately, however, this was not to be the case, because physiologists as eminent as Claude Bernard were of the opinion that lactic acid (a product of fermentation) was present in gastric contents. Indeed, as late as 1885, Ewald and Boas reported that all acid present in the stomach at the beginning of a meal was lactic. It was their theory that hydrochloric acid gradually replaced the lactic acid during eating, with the result that, by the end of a meal, only hydrochloric acid was evident.

The French Académie des Sciences was interested in the exact nature of acid in the stomach and established an essay contest for which it offered a prize of 3,000 Francs for the answer to this question. A panel of distinguished judges was selected to evaluate the essays. One year later, the prize was awarded jointly to Leuret and Lassaigne of Paris and Tiedemann and Gmelin of Heidelberg. Leuret and Lassaigne declared that the acid in gastric juice was lactic, whereas Tiedemann and Gmelin confirmed Prout’s earlier observations that it was hydrochloric acid. When asked to share the prize, the Germans declined and withdrew, having been offended by the contradiction provided by the judges. At this time, Berzelius was regarded as the ranking authority on chemistry in Europe. As a result, his comments on the literature were anxiously scanned by authors in an attempt to gauge the level of acceptance of their thoughts. Thus, Wöhler, in a letter of May 17, 1828, told Berzelius how pleased Tiedemann and Leopold Gmelin were to have noted in the Årsberättelser 7, 297 the deprecatory comments of Berzelius about the “unbedeutende Arbeit” of Leuret and Lassaigne.

The work of Leuret and Lassaigne was not inconsequential. Their experimental studies on dogs demonstrated for the first time that acid introduced into the duodenum elicited the secretion of pancreatic juice and bile.

Seventy years later, in 1894, a student of Pavlov, Ivan Leukich Dolinsky, rediscovered this effect and noted that acid in the duodenum of the dog stimulated pancreatic secretion. It was on the basis of the earlier French observations that William Bayliss and his brother-in-law, Ernest Starling, on the afternoon of January 16, 1901, tested Dolinsky’s thesis and proved the existence of chemical messengers (hormones) that regulated secretion.

Concepts of digestion

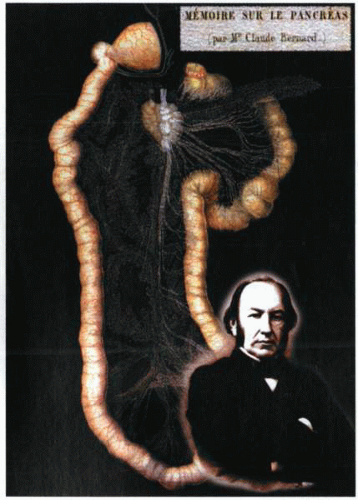

Claude Bernard (1813-1878) was born of a modest family in the town of Saint Julien on the Rhône; he attended a Jesuit college at Villefranche and then became a pharmacist’s assistant in Lyon. Bernard is best known for his book on experimental physiology, in which he outlined a number of the major concepts that he felt were critical to the pursuit of physiologic science. In particular, his delineation of the “milieu intérieur” has remained one of the critical physiologic observations ever made.

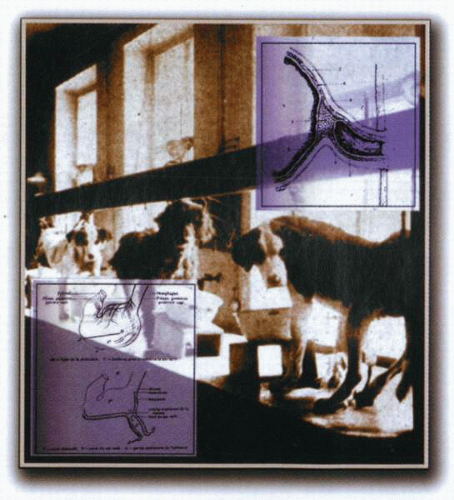

Apart from his numerous contributions, which included the identification of the glycogenic function of the liver and the delineation of the vasomotor mechanism, Bernard was noted for his contributions to the study of digestion. Before his work, it had been held that gastric digestion itself encompassed all digestive physiology. Bernard, however, demonstrated that “gastric digestion is only a preparatory act” and in particular delineated the enzymatic role of the pancreas. He demonstrated that pancreatic juice emulsified fat, converted starch into sugar, and was a solvent for proteins undigested by the stomach. Bernard was a creative investigator and had adopted Nicholas Blondlot’s canine model of the gastric fistula for the study of gastric secretion. In 1840, Blondlot of Nancy, a surgeon, had used Bernard’s innovative experimental model to determine that there was no acid or chloride in the stomach and concluded that the active principle was 1% calcium phosphate. Blondlot had been inspired to devise his canine model after reading of Beaumont’s studies of Alexis St. Martin. His innovative work in this area was later taken up by Pavlov, who constructed a series of vagally innervated and denervated pouches to evaluate the effects of neural regulation on gastric secretion. This was the so-called Pavlov pouch, which formed the basis of many of the subsequent experimental models used by the great physiologist and his pupils.

Vagal function and gastric function

Investigations on the vagus nerve began 2,000 years ago. Marinus, in the first century AD, studied the anatomy of the vagi and was the first to assign to the cranial nerves a numeric sequence. Although none of the original work by Marinus

survives today, Galen cited his studies in the second-century anatomy text On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body.

survives today, Galen cited his studies in the second-century anatomy text On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body.

Galen, who was born in Pergamon Mysia, which is now part of Turkey, in 130 AD, expanded on the work of Marinus by speculating on the possible function of the nerves to the stomach:

The stomach must have very accurate perception of the need for food and drink. Hence, most of these nerves seem to be distributed to its so-called [cardiac] orifice and afterwards to all the other portions of it as far as its lower end.

The anatomy of the vagus undoubtedly contributed to the name applied to it. The term vagus, or per vagum, means “wandering part.” A more anatomically correct name was given to the nerve in the early nineteenth century, when the term pneumogastric appeared in the French and Italian literature. It then became a frequent term in the English and American literature. In Germany, however, the nerve was always referred to as the vagus. Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century, when German scientific research attained prominence, the term pneumogastric fell from common usage in the surgical community.

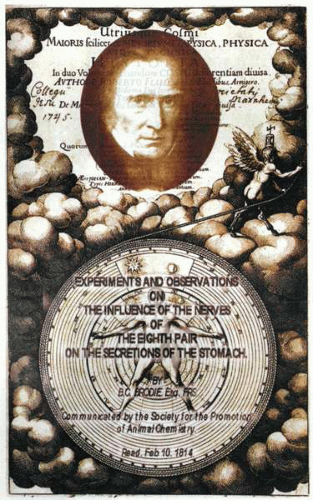

Once its anatomy became better defined, studies into vagal function were initiated. In 1814, Brodie published some of the first known experiments on vagal physiology and gastric function. In the report of his findings to the Royal Society of London, he noted that his work was inspired by Edward Home’s report of “some facts which render it probable that the various animal secretions are dependent on the influence of the nervous system.” Home, in fact, studied secretion in the electric eel:

Since in these fish the abundance of nerves connected with the electrical organs proves that this power resides in them, and since the arrangement of many nerves in animal bodies has evidently no connexion with sensation, it seems not improbable that these may answer the purpose of supplying and regulating the organs of secretion.

Thus, the observation by Home of the electric eel inspired Brodie to be the first to perform the surgical procedure that is now accepted as a vagotomy. The pioneering work of Brodie, however, was not on humans but on a total of four dogs. His first experiment was a bilateral cervical vagotomy.

He noted that this operation prevented arsenicstimulated gastric secretion but was complicated by the development of severe respiratory compromise. To remedy the subsequent respiratory embarrassment, he modified his procedure to that of a subdiaphragmatic vagotomy. With the latter operation, the animals no longer experienced the “laborious breathing” and circulatory arrest observed during cervical vagotomy.

The earlier findings of “no watery or mucous fluid in the stomach or small intestines” seen with the cervical vagotomy were confirmed in the animals that underwent abdominal vagotomy. Brodie concluded “that the suppression of secretion in all of them was to be attributed solely to the division of the nerves: and all of the facts which have been stated sufficiently demonstrate, that the secretions of the stomach are very much under the control of the nervous system.” This observation was a watershed in the history of gastrointestinal physiology, as the concept of nervous control of gastrointestinal secretion had not been previously demonstrated.

Pavlov’s delineation of vagal function

Later in the nineteenth century, Rokitansky and Bernard confirmed the findings of Brodie when they observed decreased gastric secretion and motility after vagotomy. Despite the contributions of these eminent physiologists, the modern era of the study of vagal physiology was initiated and dominated by Ivan P. Pavlov. Although he achieved principal recognition for his investigation of conditioned reflexes, his methods and the results of his observations on vagal function laid the foundation for the subsequent study of the nervous control of gastrointestinal function.

Pavlov was a graduate of the Medico-Chirurgical Academy in St. Petersburg, Russia, in the late nineteenth century. His scientific philosophy was greatly influenced by the work of Lister and Pasteur. Pavlov’s theory of “nervism” was a momentous postulate for the times in which he lived. He explained it as “a physiological theory which tries to prove that the nervous system controls the greatest possible number of bodily activities.” It was from the hypothesis of nervism that Pavlov investigated the effects of vagal stimuli on gastric secretion.

Initially, he examined the work of his predecessors and recognized that most of their experiments used cervical separation of the vagi. With this protocol,

Pavlov observed that most of the body functions of the animals “came to a standstill.” The first studies performed in his newly created modern operating rooms generated canine surgical models with diverted cervical esophagi.

Pavlov observed that most of the body functions of the animals “came to a standstill.” The first studies performed in his newly created modern operating rooms generated canine surgical models with diverted cervical esophagi.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree