Thyroid Lobectomy

Anuradha R. Bhama

Geeta Lal

The thyroid gland, the largest endocrine gland in the body, is located in the midline of the neck and is composed of two lobes connected by a midline isthmus and a variable pyramidal lobe. It is purple-pink in color and normally weighs approximately 20 g. The isthmus lies inferior to the cricoid cartilage and the lobes extend superiorly over the lateral aspects of the thyroid cartilage. In relation to the spine, the thyroid gland extends from approximately C5 to T1. It is closely associated with the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and the parathyroid glands. Success in thyroid surgery requires careful and meticulous dissection and hemostasis, which aids in the identification and preservation of these vital structures.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, has classified Partial or Total Thyroidectomy as “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedures.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Beach chair position, with neck extended and roll between scapulae

Incision 1 cm caudal to cricoid cartilage

Raise flaps in subplatysmal plane

Incise midline and mobilize strap muscles

Mobilize thyroid gland medially and divide middle thyroid vein

Mobilize superior pole and divide vessels on thyroid

Ligate inferior pole structures, working from medial to lateral

Identify recurrent laryngeal nerve

Identify and mobilize parathyroid glands

Skeletonize and divide branches of inferior thyroid artery directly on thyroid

Divide ligament of Berry

Mobilize pyramidal lobe, if present

For lobectomy, clamp and ligate isthmus on contralateral side

For total thyroidectomy, mobilize contralateral lobe as previously described

For subtotal lobectomy, leave approximately 4 g remnant posteriorly

Reapproximate strap muscles and platysma

Close incision without drainage

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Injury to recurrent laryngeal nerve

Injury to superior laryngeal nerve

Hypoparathyroidism

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Thyroid Gland and Associated Structures

Thyroid gland

Left and right lobes

Isthmus

Pyramidal lobe

Parathyroid glands

Superior parathyroid glands

Inferior parathyroid glands

Nerves

Vagus nerve (CN X)

Facial nerve (CN VII)

Spinal accessory nerve (CN XI)

Recurrent laryngeal nerve

Superior laryngeal nerve

External branch

Internal branch

Ansa cervicalis

Muscles

Platysma

Strap muscles

Sternohyoid muscle

Sternothyroid muscle

Thyrohyoid muscle

Omohyoid muscle

Sternocleidomastoid muscle

Vessels

External jugular vein

Anterior jugular vein

Jugular venous arch

Internal jugular vein

Common carotid artery

External carotid artery

Internal carotid artery

Superior thyroid vein

Middle thyroid vein

Inferior thyroid vein

Thyrocervical trunk

Superior thyroid artery

Inferior thyroid artery

Thyroid ima artery

Landmarks

Trachea

Thyroid cartilage

Cricoid cartilage

Sternal notch

Esophagus

Pretracheal fascia

Ligament of Berry

Hyoid bone

Tubercle of Zuckerkandl

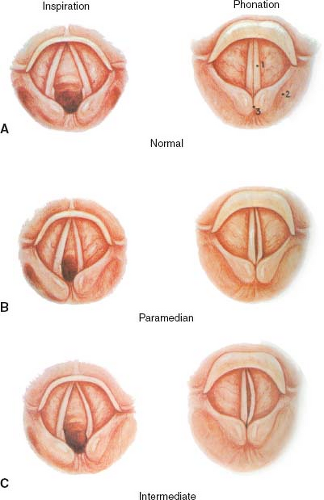

Preoperative Preparation (Fig. 6.1)

Technical Points

Patients requiring thyroid surgery should undergo careful preoperative preparation. This may include measurement of thyroid function tests, ultrasonography, fine needle aspiration, and radionucleotide scanning. To avoid thyroid storm, hyperthyroid patients should be treated with antithyroid medications, beta-blockers, and Lugol’s iodine or supersaturated potassium iodide solution, and occasionally steroids. Patients with medullary thyroid cancer should be screened for pheochromocytoma and primary hyperparathyroidism, as these conditions are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Patients who have undergone prior neck surgery or those with suspected pre-existing vocal cord dysfunction should undergo documentation of vocal cord function by direct or indirect laryngoscopy.

Anatomic Points

Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury generally results in the ipsilateral vocal cord lying in a paramedian position. Injury to both the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and the recurrent laryngeal nerve causes the vocal cord to lie in an intermediate position, as shown in Figure 6.1.

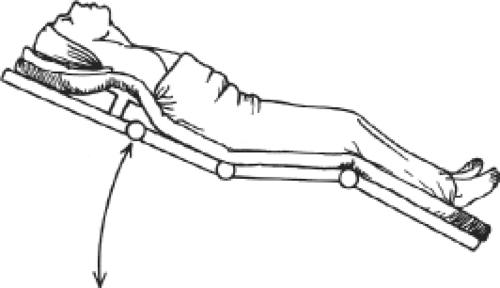

Patient Positioning (Fig. 6.2)

Technical Points

The patient should be positioned supine on the operating room table in a modified “beach chair” position, that is, with a moderate reverse Trendelenburg and with the knees flexed. This will help reduce venous pressure. Place a sandbag or roll between the scapulae allowing the shoulders to fall backward. Extend the neck and place the head on a donut cushion.

Anatomic Points

Proper positioning displaces the thyroid anteriorly and superiorly, allowing for an easier dissection. Suboptimal positioning

translates into inadequate exposure and may result in a larger incision.

translates into inadequate exposure and may result in a larger incision.

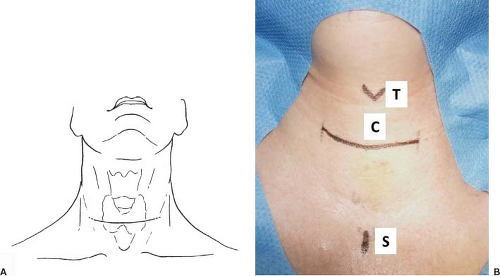

Choice of Skin Incision (Fig. 6.3)

Technical Points

Make a slightly curved transverse collar incision in a natural skin crease approximately 1 cm below the cricoid cartilage. A 2-0 silk suture may be pressed against the skin to mark out the planned course of the incision. Take care to measure the distance on each side of the midline to ensure symmetry. A 4- to 5-cm incision is generally adequate; however, patients with a short neck, large thyroid gland, or limited neck extension may require a longer incision. Carry this incision through the skin, the subcutaneous tissues, and the platysma. It is generally easier to identify the fibers of the platysma along the lateral aspect of the incision.

Anatomic Points

An incision 1 cm caudal to the cricoid cartilage generally places the incision over the thyroid isthmus. The platysma arises in the superficial fascia of the neck and is continuous with the fascia that covers the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles. It is a sheet-like muscle that extends from the mandible or the subcutaneous tissues of the face to the clavicles. Its fibers decussate over the chin and become continuous with the facial musculature. As a muscle of facial expression, it is innervated by the seventh cranial nerve.

Raising Skin Flaps (Fig. 6.4)

Technical Points

Raise the flaps in the subplatysmal plane. Place straight Kelly clamps, skin hooks, or rake retractors on the dermis to elevate the flaps anteriorly. Provide countertraction with a finger, Kitner, or gauze as the flaps are elevated, starting medially and carrying the dissection laterally, with electrocautery and/or a scalpel. Sometimes, portions of this dissection can be accomplished bluntly with a Kitner. Extend this elevation superiorly to the level of the thyroid cartilage and inferiorly to the level of the suprasternal notch. Take care not to injure the superficial network of veins that lie deep to the platysma. This potentially extensive collection of veins, including the paired anterior jugular veins, external jugular veins, and communicating veins, lies beneath the platysma muscle, overlying the sternocleidomastoid and midline strap muscles. Place towels along the skin edges to protect them and use a self-retaining retractor to aid in exposure.

Anatomic Points

Elevating subplatysmal flaps takes advantage of an avascular plane that lies between the platysma and the underlying superficial veins and strap muscles. The muscles encountered during thyroid surgery become apparent after the mobilization of subplatysmal flaps. These include the sternocleidomastoid muscles and the paired strap muscles (sternohyoid, sternothyroid, thyrohyoid, and omohyoid muscles). The sternocleidomastoid muscles mark the lateral boundaries of the dissection. The sternocleidomastoid muscle has two muscle bellies, both inserting onto the mastoid process with dual origins, on the sternum and the proximal clavicle. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is innervated by the spinal accessory nerve (CN XI). The omohyoid muscle inserts on the hyoid bone and originates from the scapula. Only the superior belly is generally encountered. The sternohyoid muscles lie in the midline overlying the sternothyroid and thyrohyoid muscles. The sternohyoid originates from the sternum and inserts on the hyoid bone. The sternothyroid extends from the sternum to the thyroid cartilage, and the thyrohyoid muscle extends from the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone.

The superficial jugular veins lie just beneath the platysma. The paired external jugular veins lie laterally and over the sternocleidomastoid muscles. The paired anterior jugular veins directly overlie the sternohyoid muscles. There is often an extensive network of communicating veins connecting the anterior jugular veins and the external jugular veins. The jugular venous arch, a communication between the right and left anterior jugular veins, is often seen in the lower part of the neck and may have to be ligated and divided to provide optimal exposure and separation of the strap muscles. Although ligation of these veins is of little clinical consequence, identification and avoidance of these vessels is often possible.

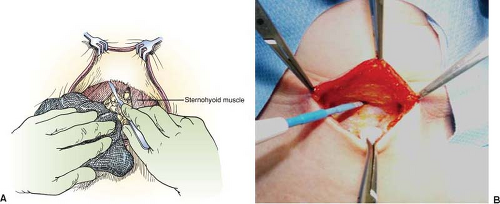

Division/Mobilization of Strap Muscles (Fig. 6.5)

Technical Points

Identify the midline raphe between the paired strap muscles. Using electrocautery, separate the paired sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles in the midline from the sternal notch to the thyroid cartilage to expose the underlying thyroid gland. On the side to be approached first, bluntly dissect the sternohyoid muscle from the deeper sternothyroid muscle lying just beneath it. This step often assists with exposure, particularly when working via smaller incisions. Identify and preserve the ansa cervicalis as it courses over the lateral aspect of the sternothyroid, if possible. Then dissect the sternothyroid muscle off the thyroid bluntly. Identify the internal jugular vein by gently retracting laterally on the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The strap muscles may occasionally require division to gain exposure to the thyroid gland, particularly in large goiters. In the rare occasion that division is necessary, divide the muscles as high as possible to preserve the strap muscles’ innervation by the ansa cervicalis. These muscles can then be sutured together at the end of the operation. If a tumor directly invades into the strap muscles, resect the strap muscle en bloc with the underlying thyroid tissue.

Anatomic Points

The thyroid gland lies deep to the strap muscles. Dividing the midline raphe between the left and right sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles and retracting the muscles laterally allows visualization of the thyroid gland. The midline raphe between the strap muscles represents a condensation

of the superficial layer of deep cervical fascia. The strap muscles are farthest apart just above the suprasternal notch, making this the ideal spot to start the dissection. The thyrohyoid muscle is innervated by a branch of the first cervical nerve, and the remaining strap muscles are innervated by the ansa cervicalis (C1 to C3). Although denervation of the strap muscles is of little clinical significance, it may lead to subtle changes in swallowing and cosmesis. Preservation of the ansa cervicalis is therefore desired. Motor branches of the ansa cervicalis usually enter the muscles at two points, near the level of the thyroid cartilage and just cephalad to the sternal notch. The underlying thyroid is purple-pink in color and its surrounding capsule represents the division of the deep pretracheal fascia of the neck into the anterior and posterior divisions.

of the superficial layer of deep cervical fascia. The strap muscles are farthest apart just above the suprasternal notch, making this the ideal spot to start the dissection. The thyrohyoid muscle is innervated by a branch of the first cervical nerve, and the remaining strap muscles are innervated by the ansa cervicalis (C1 to C3). Although denervation of the strap muscles is of little clinical significance, it may lead to subtle changes in swallowing and cosmesis. Preservation of the ansa cervicalis is therefore desired. Motor branches of the ansa cervicalis usually enter the muscles at two points, near the level of the thyroid cartilage and just cephalad to the sternal notch. The underlying thyroid is purple-pink in color and its surrounding capsule represents the division of the deep pretracheal fascia of the neck into the anterior and posterior divisions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree