The Shouldice Method of Inguinal Herniorrhaphy

Robert Bendavid

In an Atlas of Hernia Surgery, all roads lead to Bassini.

—R. Bendavid (2005)

The treatment of inguinal hernias can truly be said to be following an orderly process of evolution. Much credit goes to the anatomists who described the important structures: Poupart, Hesselbach, Cooper, Thomson, Gimbernat, and Fruchaud, to name a few. The next step in this evolution was contributed by the surgeons: Bassini, Ruggi, Narath, Lotheissen, Halsted, and McVay, to name a few. From the late 1940s to the early 1950s, the introduction of synthetics provided the surgeon with a weapon that promised a certain cure and among the pioneers one must recall Acquaviva, Zagdoun and Sordinas, Newman, Lichtenstein, Rives, and Stoppa. From the early 1990s we have seen the introduction of laparoscopy and the emergence of a controversy that is far from settled in terms of safety, cost, learning curve, and complications. Experience reveals that, despite the advances made in the field of hernia surgery where prostheses and laparoscopy have made significant contributions, the need to know anatomy and to be able to perform a pure tissue repair has become indispensable and imperative. Recurrences are still common and often the result of inadequate dissection, failure to recognize a hernia, repair under tension, or an inappropriate use of a prosthesis, the latter being often, blindly, and erroneously considered a panacea for any and all hernias. Each of the above factors can be addressed effectively when one is familiar with anatomy. The anatomy of the groin is, by no means, the easiest to understand, incorporate, or retain!

As anatomy became clearer, early progress was achieved by the introduction of steps that would in some way improve pure tissue hernia repair. Among these steps, the following stand out:

Division of the posterior inguinal wall (Bassini, McVay, Fruchaud)

Ligation of the hernia sac (Championniere, Marcy, Bassini, Fruchaud)

Resection of the cremaster (Bassini)

Use of the iliopectineal ligament (Narath, Lotheissen, McVay, Ruggi)

Appreciation of the iliopubic tract or bandelette of Thomson (Fruchaud, Condon, Nyhus)

Reconstruction of the posterior inguinal wall (Bassini, Halsted, McVay)

This process of evolution remains manifest as surgeons attempt and evaluate newer techniques. Among the controversial points, one is the value of resection of the hernial sac. Many surgeons believe that an adequate posterior inguinal wall reconstruction would be sufficient to contain the sac and, hence, a hernia. Others consider the resection of the cremaster unnecessary, particularly if a prosthetic repair is considered as an alternative for reconstruction of the posterior inguinal wall. Others still never split the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, under the pretext that this maneuver only promotes the formation of a recurrent hernia. An important aspect of this ongoing evolution in hernia surgery is the introduction of various mesh prostheses through open techniques or laparoscopy and their acceptance as part of the modern treatment of primary as well as the more difficult recurrent inguinal hernias.

The contribution of the Shouldice philosophy in this evolution is simply that it has chosen and implemented the specific steps that have been introduced over the past 120 years. More exactly, in the early 1950s, it was the well-informed staff surgeon Ernie Ryan, a recent addition to the Shouldice Hospital staff, who incorporated all the specific steps of the Bassini repair, which had been known since 1886. Bassini himself had brought together the pieces of this puzzle by acknowledging and implementing the observations of all the previously named surgeons. Bassini had, in a sense, gleaned the fertile fields of the past to produce an operation that was unique, original, and effective, and that would be emulated by at least a 100 techniques of pure tissue repairs to date. The Shouldice repair remains the most faithful reflection of the Bassini technique and therefore its success.

Historical Background

E. E. Shouldice became interested in the treatment of inguinal hernias in the 1930s. Operative results were then notoriously poor. In addition to attempts at perfecting his surgical technique, Shouldice looked on each patient as an individual who was to be cared for preoperatively as well as postoperatively.

Obesity, the bane of all surgery, was a factor that had to be brought under control before an operation. To that end, a clinic was set up where patients were to be evaluated while on a weight-reducing diet until their ideal weight was reached. Early ambulation was to be instituted postoperatively in a manner that was then considered heretical, namely, the patient walked away from the operating table, bed rest was minimal, and all activities were to be resumed as soon as possible without restriction. Only the patient’s discomfort was a limiting factor. Such an approach had been emphasized by Leithauser in a voluminous publication, which he dedicated strictly to the subject of early ambulation. Shouldice, as evidenced by the correspondence he kept, was in contact with Leithauser and became an enthusiastic, adept, and firm believer in the postulates and advantages of early mobilization following all surgical operations.

Local anesthesia was of paramount importance and, to that end, procaine was retained. The basis for this choice of anesthesia was the actual safety of the technique as had been reported convincingly by Halsted, Bloodgood, and Cushing of Johns Hopkins who had published two series of inguinal hernia repairs carried out under local cocaine anesthesia. Cushing at that time provided the most accurate and unparalleled mapping of the innervation of the groin.

Perhaps the most critical contribution was to be the institution of a follow-up system. Unfortunately, the original follow-up and publication of a large series by Iles was flawed and statistics have followed in the same manner, where one is overwhelmed by staggering numbers, but without a closer scrutiny by a professional statistician. Two excellent studies from the Shouldice Hospital would subsequently confirm the serious flaw about the accuracy of their follow-up (Obney and Chan, Bendavid) and provide a more realistic assessment of their results.

The need for a center specializing in external hernias of the abdominal wall was fulfilled in 1945 when the Shouldice Hospital was established. With 10 full-time surgeons, about 7,500 operations are performed every year.

General Principles

Anatomy

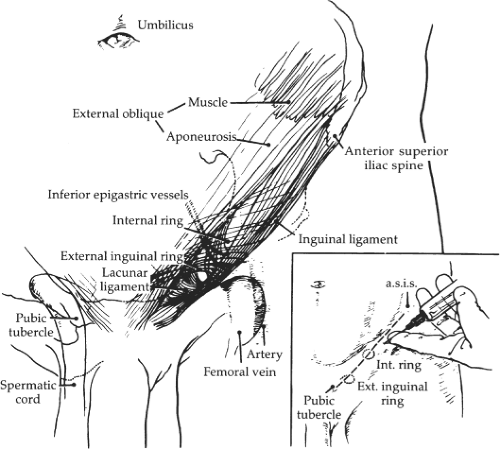

The inguinal region is arguably one of the most complex anatomic areas of the human

body. One obvious obstacle is the nomenclature, a nomenclature that is academically correct and in place but whose irreverent usage has been corrupted and turned into a vocabulary reminiscent of a bad weed that has been difficult to eradicate. Cooper and Fruchaud are the two authors whose books have contributed most to the clarity and understanding of the groin. Unfortunately, those books have become extremely rare and, when found, unaffordable. For a necessary understanding of the groin, it is imperative that we clarify certain terms and that we adhere to them. It is crucial at all times to remember that anatomy is described with the subject in the standing position. The posterior inguinal wall must never be referred to as the “floor of the canal” as is done too frequently because of the supine position of a subject during surgery, when the posterior inguinal wall presents itself as the floor of the canal simply because it is parallel to the ground!

body. One obvious obstacle is the nomenclature, a nomenclature that is academically correct and in place but whose irreverent usage has been corrupted and turned into a vocabulary reminiscent of a bad weed that has been difficult to eradicate. Cooper and Fruchaud are the two authors whose books have contributed most to the clarity and understanding of the groin. Unfortunately, those books have become extremely rare and, when found, unaffordable. For a necessary understanding of the groin, it is imperative that we clarify certain terms and that we adhere to them. It is crucial at all times to remember that anatomy is described with the subject in the standing position. The posterior inguinal wall must never be referred to as the “floor of the canal” as is done too frequently because of the supine position of a subject during surgery, when the posterior inguinal wall presents itself as the floor of the canal simply because it is parallel to the ground!

The transversalis fascia is part of the endoabdominal fascia and is the deepest part of the posterior inguinal wall. It is a thin layer that has no bearing on the genesis of a hernia though it may precede the peritoneum, and this is best seen with direct inguinal hernias. The true posterior inguinal wall is formed by the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis. It is this layer, when it is weak and degenerated, that is seen to bulge and appear as a direct hernia, followed by the true transversalis fascia and peritoneum. What constitutes the true defect leading up to a direct inguinal hernia is a weakness of a layer of connective tissue situated between the transversus aponeurosis and the transversalis fascia and that Fruchaud has described as the vascular lamina. Posteriorly, in the retroinguinal space of Bogros this is referred to as the inferior epigastric lamina, which extends medial to but not lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. It is a connective tissue layer that degenerates as a result of the metabolic defects that lead to hernias. These metabolic defects are beginning to be understood and account for the genesis of all hernias, regardless of their site.

Weight Control

Every effort is made to obtain the patient’s cooperation in shedding excess weight. This may require months, but the dividends are obvious and are reflected in an easier operation technically, in less tension during approximation of tissue layers, in early ambulation, and in a lesser incidence of thrombophlebitis and pulmonary complications. Ironically, with inguinal hernias, there does not seem to be a convincing correlation between obesity and recurrences. The same cannot be said of incisional hernias. Still, the benefits of a lean patient are evident from both the patient’s and surgeon’s point of view.

Table 1 Patient Population Older than Age 50a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sedation

On the evening before the operation, all patients are given a sedative (diazepam, 5 to 10 mg) orally. On the day of operation, diazepam (10 to 25 mg) is given orally 90 minutes preoperatively, and meperidine (25 to 100 mg) is given intramuscularly 45 minutes preoperatively. These sedatives and analgesics can be varied and often are.

Anesthesia

Local anesthesia is used in 95% of operations. At the Shouldice Hospital, procaine hydrochloride has been used since 1945. It is an excellent drug; it takes effect within minutes, and this effect lasts as long as 2 hours. The effective concentration for the duration of the procedure is a 1% solution, with a maximum volume of 200 mL.

The desirability of local anesthesia may be appreciated when analyzing the patient population. A study at the Shouldice Hospital subsequently published revealed that 52.1% of all patients coming to surgery were older than 50 years (Table 1). Significant associated cardiac problems range from 15% to 50% (Table 2). The safety of local anesthesia increases the pool of patients who may undergo surgery. An added advantage is the lesser need for extensive consultations and investigations to assess the fitness of a patient to undergo surgery. This, in turn, drives down the cost of health care.

Surgical Principles

The surgical aspect of the Shouldice Hospital repair can be broken down into two components: dissection and reconstruction. Before discussing each phase in detail, it would be of interest to emphasize some aspects of the procedure and to justify their importance. It must be stated that, at the Shouldice Hospital, though the technique is generally the same, all surgeons vary to a certain extent. These variations usually have to do with the degree of tension on sutures, the size of tissue bites incorporated, the extent of the dissection, full or partial division of the posterior wall of the canal, and time taken to perform a procedure.

Table 2 Incidence of Associated Conditions in Patients Older than Age 50 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Incision

The incision is lower than is described in most textbooks. It is made along a line joining the anterosuperior iliac spine and the pubic crest. This incision, once made, brings the inguinal area into full view without a strenuous retraction. The latter can be a source of discomfort under local anesthesia. The exposure, about the inguinal ligament, becomes ideal, and so does the pubic crest area.

External Oblique Muscle and Aponeurosis

The incision into the external oblique aponeurosis is extended from the superficial inguinal ring to a point 2 to 4 cm lateral to the deep inguinal ring. This allows a thorough dissection of the deep ring and examination

of the substance and quality of the fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. Often, fatty infiltration of these muscles is seen near the deep ring, usually laterally and superolaterally, providing poor tissue for repair. One may also find preperitoneal fat protruding through this area, setting the stage for an interstitial hernia, a recurrent inguinal hernia, or an overlooked hernia. If need be, the deep ring is relocated by incising laterally the internal oblique and transversus abdominis fibers over a length of 1 to 3 cm.

of the substance and quality of the fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. Often, fatty infiltration of these muscles is seen near the deep ring, usually laterally and superolaterally, providing poor tissue for repair. One may also find preperitoneal fat protruding through this area, setting the stage for an interstitial hernia, a recurrent inguinal hernia, or an overlooked hernia. If need be, the deep ring is relocated by incising laterally the internal oblique and transversus abdominis fibers over a length of 1 to 3 cm.

Resection of the Cremaster

This important step seems to have been entirely forgotten. Few students have seen it performed, and fewer surgeons practice it. This step was clearly described and emphasized by Bassini, repeated by Catterina, and perpetuated by Shouldice. The resection of the cremaster and lateral retraction of the cord bring into view the posterior inguinal wall in a manner that can best be described as a “revelation.” It becomes impossible, then, to overlook a direct or indirect inguinal hernia. The transversus abdominis aponeurosis (i.e., the posterior inguinal wall) is now in full view. Whenever possible, the cremasteric vessels should be doubly ligated separately from the cremasteric muscle.

Incision of the Posterior Wall of the Inguinal Canal

Division of the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia (the true transversalis fascia, which is part of the endopelvic fascia and which lines the deep aspect of the groin) from the internal ring to the pubic crest is of paramount importance. It serves the purpose of identifying all hernial defects, however small. Redundant and weak transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascias medial and lateral to the incision can be excised; this excision then defines the new edges, which will be sutured into the new posterior wall of the inguinal area.

In women, division of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal is not as crucial. Nevertheless, the lateral third of this wall must be incised to allow proper examination of the entire posterior wall and to verify the absence of a femoral hernia from the preperitoneal space, above the inguinal ligament. This attitude with regard to female patients was confirmed by a study carried out by Glassow. Between 1945 and 1959, 27,870 abdominal wall herniorrhaphies were performed, 676 of them on women. Of these 676 inguinal hernias, 605 were indirect inguinal hernias (592 primary and 13 recurrences) and 71 were direct inguinal hernias (50 primary and 21 recurrences). Of the 50 primary direct inguinal hernias, 40 were accurately documented. The defect was located in the lateral half of the floor in 32 patients and in the medial half of the floor in eight patients. The solidity of the posterior inguinal floor in women is a fact easily observed in practice. The aforementioned figures place the incidence of a direct inguinal hernia in a woman at 0.2% of all abdominal wall hernias.

Search for A Peritoneal Protrusion

The search for a peritoneal protrusion must become a ritual. The experience of the Shouldice Hospital reveals that of all patients with recurrent inguinal hernias referred to that institution, 37% prove to have indirect inguinal hernias. It becomes imperative, then, during all inguinal herniorrhaphies to look for a peritoneal protrusion if an indirect sac is not identified. This protrusion is found on the medial aspect of the spermatic cord within the internal ring and deeper, closely adherent to the vas, from which it must be freed and allowed to retract back into the preperitoneal space. The presence of a peritoneal protrusion confirms the absence of an indirect inguinal hernia. Very rarely, two indirect sacs can be present.

Ligation of the Sac

The ligation and resection of a hernia sac can be likened to a symbolic gesture representing victory of surgery over disease. Most surgeons have resected this sac in the past, understandably so if it is elongated, tubular, or scarred or if strictures are present. Is “high” proximal or even simple resection necessary? Experience relating to sliding inguinal hernias reveals that once a sac and its contents are freed from the spermatic cord, the entire sac, regardless of its size, can simply and reliably be returned into the abdominal cavity. This fact emphasizes the importance and necessity of a good posterior inguinal wall and of its reconstruction as a barrier against recurrent herniation. It has been shown by Ryan and Welsh that the incidence of recurrence after repair of sliding indirect inguinal hernias is less than 1%. What is important, therefore, is that the dissection of an indirect sac be carried out as far as possible deep to the already enlarged internal ring. Once the sac is ligated (“high” or “low”) or even if it remains intact, it should easily be replaced and made to disappear in the preperitoneal space.

Sliding Hernias

Sliding hernias need not present a problem. A surgeon about to enter practice generally anticipates with trepidation the first encounter with a “slider.” So many procedures, often difficult to illustrate, abound in many texts and always prove to be confusing at best. In a report of 2,300 operations from the Shouldice Hospital analyzed by Welsh, only 11 recurrences were recorded. Of these 11, only one was a true recurrent sliding inguinal hernia; the other recurrences were five femoral hernias and five direct inguinal hernias. The standard Shouldice Hospital repair was used in each of the 2,300 operations. The emphasis here is on resection of the cremaster muscle; the proper dissection of the internal ring, which is already and usually enlarged, and resection of a peritoneal sac if such can be carried out safely. I generally prefer to leave the sac intact and simply reduce it. “High” ligation must never be the aim. If the least doubt emerges as to whether the sac can be safely incised, the sac must be left alone and returned to the preperitoneal space intact. This never presents a problem, because 90% of sliding hernias are easily reducible and do so spontaneously before surgical intervention.

Release of the Cribriform Fascia (Thigh Fascia)

After incision of the external oblique aponeurosis along the direction of its fibers, its lateral flap is held taut anteriorly and the fascia cribriforms, beneath the inguinal ligament, is incised from the level of the femoral vein to the medial aspect of the pectineus muscle. This maneuver frees the external oblique aponeurosis to an extent that makes it widely available for the inguinal repair. This step can be compared with the creation of a flap or a “plasty” or relaxing incision. This maneuver also allows examination of infrainguinal, femoral herniation.

Search for Multiple Hernias

Statistics show that a second, simultaneous, ipsilateral hernia was found, if adequately searched for, in 12.8% of the patients who underwent operation. This search in all instances must rule out an indirect hernia, a direct hernia, a femoral hernia, an interstitial hernia, a prevascular hernia, a Laugier hernia (through the lacunar ligament), a prevesicular hernia (anterior to the bladder), and, lastly, lipomas, which on occasion perforate through the internal oblique and transversus muscles at

the deep inguinal ring. The search must be established as a routine.

the deep inguinal ring. The search must be established as a routine.

Relocation of the Superficial Ring

During reconstruction of the posterior inguinal wall, as we shall see, the fourth line of suture tacks down the medial 2 to 3 cm of the external oblique aponeurosis (the lateral flap) in such a manner as to cover the medial portion of the floor of the canal. This is the site of recurrence of most direct inguinal hernias (69.2% of recurrent direct inguinal hernias as reported by Obney and Chan). As a result, the superficial ring becomes relocated in a position slightly lateral from its original site.

Continuous, Nonabsorbable Suture

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree