Overview

With increasing public attention to patient safety have come calls for more participation by patients and their advocates in the search for solutions. Some of these calls have focused on individual healthcare organizations, such as efforts to include patients on hospital safety committees.1 Most, however, have involved enlisting patients in efforts to improve their own individual safety—often framed as a version of the question: “What can patients do to protect themselves?” This chapter will explore some of the opportunities and challenges surrounding patient engagement in their own safety, including errors caused by patients themselves. The issues surrounding disclosure of errors to patients are covered in Chapter 18.

Patients with Limited English Proficiency

A previously healthy 10-month-old girl was taken to a pediatrician’s office by her monolingual Spanish-speaking parents, worried about their daughter’s generalized weakness. The infant was diagnosed with iron-deficiency anemia. At the time of the clinic visit, no Spanish-speaking staff or interpreters were available. One of the nurses spoke broken Spanish and in general terms was able to explain that the girl had “low blood” and needed to take a medication. The parents nodded in understanding. The pediatrician wrote the following prescription in English:

Fer-Gen-Sol iron, 15 mg per 0.6 mL, 1.2 mL daily (3.5 mg/kg)

The parents took the prescription to the pharmacy. The local pharmacy did not have a Spanish-speaking pharmacist on staff, nor did they obtain an interpreter. The pharmacist attempted to demonstrate proper dosing and administration using the medication dropper and the parents nodded their understanding. The prescription label on the bottle was written in English.

The parents administered the medication at home and, within 15 minutes, the baby vomited twice and appeared ill. They took her to the nearest emergency department, where the serum iron level one hour after ingestion was found to be 365 mcg/dL, twice the upper therapeutic limit. She was admitted to the hospital for intravenous hydration and observation. On questioning, the parents stated that they had given their child a tablespoon of the medication, a 12.5-fold overdose. Luckily, the baby rapidly improved and was discharged the next day.2

Any discussion of patient engagement needs to start from square one—do patients understand their care and the benefits and risks of various diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (i.e., informed consent)? If patients cannot understand the basics of their clinical care, it seems unlikely that they can advocate for themselves when it comes to safety.

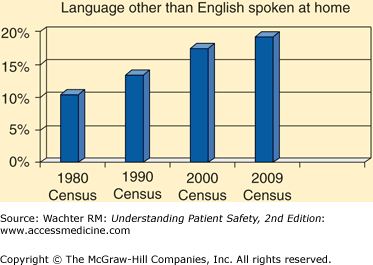

Unfortunately, many patients are in no position to understand even the basics of their care, let alone serve as bulwarks against errors. First of all, nearly 60 million Americans (20% of the population) speak a primary language other than English at home, and 25 million have limited English proficiency.3 Both of these populations nearly doubled in the United States between 1980 and 2009 (Figure 21-1). Few hospitals have adequate translation services4—translation frequently takes place on an ad hoc basis, often by untrained clerical personnel or even family members.5 In one case, an 11-year-old sibling interpreter made 58 interpretation errors, 84% of which had potential clinical consequences.6

Language barriers increase the chances of adverse events.7 One UCSF study found that non-English-speaking patients had a 30% higher odds of 30-day readmission to the hospital than did English speakers.8 Other studies have documented poorer adherence to treatment and follow-up, decreased satisfaction with care, decreased comprehension of diagnosis and treatment plans, and more adverse drug events.9–12 The use of professional interpreters is associated with fewer communication errors, better patient comprehension, higher patient satisfaction, and improved clinical outcomes.13

Although state and federal legislation requires that adequate interpreting services be made available to limited English proficiency patients, the costs and scarcity of trained interpreters have made it difficult to ensure universal access to these services.14 The increasingly widespread use of new communication technologies, including telephonic (Figure 21-2) and video interpreter services and even Web-based voice recognition and translation services, represents a hopeful trend.15,16

Patients with Low Health Literacy

Even when patients do speak English well, many are at risk because of low “health literacy,” which is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”17 It includes the skills that patients need to communicate with providers, read medical information, make decisions about treatments, carry out care regimens, and decide when and how to seek help.

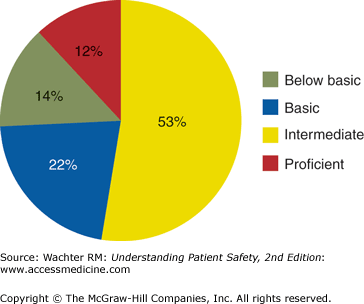

In 2003, approximately 80 million U.S. adults (36%) had limited health literacy18 (Figure 21-3); the problems are greater in patients with lower income, less education, and lower English language proficiency. Low health literacy is associated with poor communication between patients and clinicians and worse health outcomes.18–20 Medication errors are a particular problem: studies have shown that patients with poor health literacy frequently misunderstand common dosing regimens (“Take one tablet by mouth twice daily”) and auxiliary warnings (e.g., Do not chew or crush; For external use only).21

Figure 21-3

Health literacy of adults in the United States. Below basic: circle date on doctor’s appointment slip. Basic: give two reasons a person with no symptoms should get tested for cancer based on a clearly written pamphlet. Intermediate: determine what time to take Rx medicine based on label. Proficient: calculate employee share of health insurance costs using table. (Reproduced with permission from National Assessment of Adult Literacy, National Center for Educational Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, 2003.)

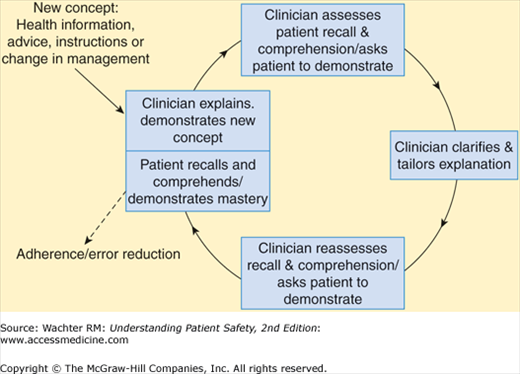

A number of strategies have been employed to mitigate the effects of low health literacy on safety. Many of them have focused on identifying patients with low literacy,22,23 and then providing them with simplified health materials (such as brochures and medication labels), Web sites, and interactive videos.24 Newer interventions focus on training providers to interact with low health literacy patients in appropriate ways. For example, the use of the “teach back” (patients are asked to restate to the provider their understanding of their condition or treatment plan) can help ensure that patients truly comprehend their situation (Figure 21-4).25,26 An alternative strategy is the “Ask Me 3,” which prompts patients to ask their providers three questions: What is my main problem? What do I need to do? Why is it important for me to do this?27 Patients who appear not to understand their care plan receive additional help.

In addition to these targeted interventions at the point of care, it will be important to embed education about health literacy into the training of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. For example, a number of the newer competencies for residents involve issues of doctor–patient communication and improving physicians’ sensitivity to patients’ varying communication styles and needs. Because so many of the problems surrounding health literacy revolve around medications,18,20,24,28 the involvement of trained pharmacists can be crucial.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree