The Role of Military Medicine in Civilian Disaster Response

Brian A. Krakover

INTRODUCTION

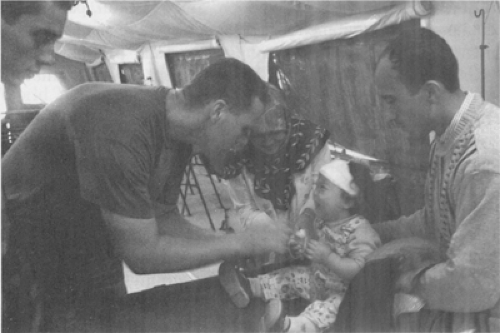

Military medical units have played an important role in recent natural disasters and may be called on in the future to assist civilian agencies with medical response to future terrorist attacks (Fig. 38-1). Emergency response to future terrorist events will likely require federal assistance, and there is a plan in place, aptly named the Initial National Response Plan, which addresses many of the mechanics associated with that aid. This plan replaces the Federal Response Plan and will be replaced with a final National Response Plan at a future date. However, there are over 85,000 local jurisdictions for the military to support, and the doctrine that governs how the military will support civil authorities in disaster response is still under development (1).

PREPAREDNESS ESSENTIALS

In response to the events of September 11, the president of the United States and Congress established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to consolidate homeland security and civil support under a single organization, and the Department of Defense (DoD) established Northern Command (NORTHCOM) to consolidate homeland defense and civil support under a single command. Critical homeland security plans, policies, and procedures are still being debated and have not been finalized by national and state decision makers. The interaction of the DHS, the assistant secretary of defense for HLS, and NORTHCOM is still developing (1).

RULES REGARDING THE USE OF FEDERAL TROOPS

The policy that governs most limitations placed on the military’s actions in domestic conflict is the well-known but less well understood Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 (2). The act was initially intended “to end the use of federal troops to police state elections in former Confederate states” (2). However, this Reconstruction era law is used today to keep the military from participating in domestic law enforcement. This restriction was one of the principal issues in the investigation of the military’s involvement in the Branch Davidian assault, and it continues as a source of controversy for DoD domestic counternarcotic and counterterrorist operations (3). Many questions remain regarding the military’s role in domestic terror incidents (3). As long as the federal bureaucracy defines terrorism as a law enforcement issue rather than a national security issue, the DoD faces considerable legal limits on its ability to act to counter domestic terrorism. However, Posse Comitatus is not the absolute prohibition that many consider it to be (4). A rather significant loophole is written directly into the law:

Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force (later to include Navy and United States Marine Corps as well) as a Posse Comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned not more than two years, or both (5).

Thus it appears that the president or Congress may authorize the use of federal military forces for domestic use if they deem an indication exists (3). Significant recent exceptions to the act have included disaster relief operations under the Stafford Act, the “drug exception” authorized by Congress to fight the “war on drugs,” border patrol operations along the Mexican border, and the military assistance provided to state and local governments under the Domestic Preparedness Program (3).

CHAIN OF COMMAND

At Oklahoma City, New York City, and the Pentagon, the incident commander in each case was a civilian fire chief,

and the military was in support of that fire chief. That will most likely be the model for the future. Although a standardized incident command system is a step in the right direction, more still needs to be done in order to mitigate efficiently the damages that come from a terrorist attack. Under these circumstances, it is often not possible to evacuate all those who would benefit, and the ability to move surgical beds and health care providers into the area of operations may become important. To affect mortality significantly, however, trauma surgery must be available within minutes or hours, and overall surgical needs after an earthquake fall off sharply after the initial 72 hours (6). Although causing severe damage to health care facility structures, recent hurricanes in the United States have not resulted in large numbers of deaths and serious injuries, but they provide an appropriate analogy for a response to future terrorist attack. Military medical units offer an attractive way to augment patient care capabilities rapidly in a civilian disaster situation (6). In order to activate military medical forces for civilian disaster assistance, the state or local authorities, usually the governor, must make a request to the assistant secretary of defense for special operations and low-intensity conflict (SOLIC) for additional resources. The ASD-SOLIC is authorized by the DoD to designate the U.S. Army as the lead agency in cases of suspected domestic terrorism.

and the military was in support of that fire chief. That will most likely be the model for the future. Although a standardized incident command system is a step in the right direction, more still needs to be done in order to mitigate efficiently the damages that come from a terrorist attack. Under these circumstances, it is often not possible to evacuate all those who would benefit, and the ability to move surgical beds and health care providers into the area of operations may become important. To affect mortality significantly, however, trauma surgery must be available within minutes or hours, and overall surgical needs after an earthquake fall off sharply after the initial 72 hours (6). Although causing severe damage to health care facility structures, recent hurricanes in the United States have not resulted in large numbers of deaths and serious injuries, but they provide an appropriate analogy for a response to future terrorist attack. Military medical units offer an attractive way to augment patient care capabilities rapidly in a civilian disaster situation (6). In order to activate military medical forces for civilian disaster assistance, the state or local authorities, usually the governor, must make a request to the assistant secretary of defense for special operations and low-intensity conflict (SOLIC) for additional resources. The ASD-SOLIC is authorized by the DoD to designate the U.S. Army as the lead agency in cases of suspected domestic terrorism.

NATIONAL DISASTER MEDICAL SYSTEM

The National Disaster Medical System is a federally coordinated network of health care facilities that augments the nation’s emergency response capability in case of disaster. The NDMS has the main responsibility for assisting state and local authorities in responding to major peacetime domestic disasters as well as augmenting the VA and DoD Contingency Hospital System for receiving casualties in times of war. DoD military hospitals, also known as MTFs (medical treatment facilities), make a significant contribution to the NDMS in civilian disasters by serving as Federal Coordinating Centers, or FCCs. The FCC, according to the Federal Response Plan, is a facility located in a U.S. metropolitan area responsible for daily coordination of planning and operations in an assigned NDMS region or Patient Reception Area (PRA) (7) (Table 38-1).

HISTORICAL EVENTS

MILITARY MEDICINE IN SUPPORT OF RECENT NATURAL DISASTERS

The U.S. armed forces have been involved in domestic disaster response activities since the end of the Civil War, and the reasons for using the military during these operations, including the ability to provide resources and organizational capabilities quickly, have not changed greatly since those early years (6). The medical literature describes two major deployments of military medical units to help with civilian disaster response.

On the evening of September 15, 1995, Hurricane Marilyn struck the island of St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). The U.S. Army’s 28th Combat Support Hospital was alerted for deployment on day 3. The territorial governor requested federal assistance because the island’s only hospital was severely damaged by the storm. The CSH was able to provide medical and surgical beds, a neonatal ward, labor and delivery rooms, an eight-bed emergency room, and two 12-bed intensive care units (ICUs) based out of tents. They were also able to provide hospital laundry, pharmacy, radiology, and maintenance capabilities. Despite legal, financial,

and political concerns, the unit was able to care for a desperate patient population in need and to provide sustained capabilities while local health care facilities were rebuilt.

and political concerns, the unit was able to care for a desperate patient population in need and to provide sustained capabilities while local health care facilities were rebuilt.

TABLE 38-1 U.S. Contingency Bed Hospital Capacity (16)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|