Introduction

All healthcare leaders rely on communication as the essential tool in setting plans, getting results, and continuously developing their staff. In our work with healthcare leaders, we have learned many lessons which are not only effective in the unique healthcare business arena, but have been translated across to professions such as school administration and corporate organizations. In this chapter, we will explore a practical strategy for maximizing strategic leadership communication copyrighted as the PACT System. This system has not only been validated through field use over the past 20 years in an array of organizations, but more importantly, it is an intuitive system which can be readily understood and practically applied immediately to your organization and specific leadership responsibilities.

The PACT acronym stands for the four essential values that are expected in all leadership communication, and indeed, as centric elements of organizational strategy—pride, accountability, commitment, and trust. Each value is augmented by a set of couplets that portray the pros and cons of specific action relative to the value, in essence, what happens when a leader adheres to the constructive, positive aspect of a particular factor, and the liabilities and fallacy of inadvertently employing the negative, regressive side of the particular tenet. The chapter is premised on a handbook of over 500 PACT Factors currently employed by the physician leadership cadre of New Jersey’s largest medical and healthcare systems, as well as many sectors of the Veterans Administration Health System. We have selected for you the most prominent and universal strategies in the hope that a number of them will have immediate value in your specific situation, as is the intent of this entire book. As you will soon see, they are logical in construct, easy to grasp, and very practical in their application regardless of your particular leadership role, as they are all based on the real world of strategic leadership communication that we work in every day.

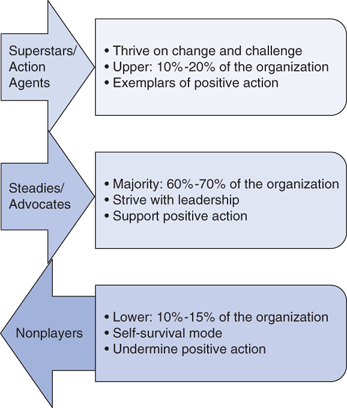

The Performance Matrix

In order to put this chapter in context, we begin with the performance matrix (see Figure 2–1), which depicts the basic three performance categories of any work team. Superstars, or action agents, drive the action and are the exemplars of a work unit. They thrive on change, lead the action, define excellence within the organization, act as positive charismatic physician leaders, and fully support the team’s goals and organization’s mission through their performance. They need little encouragement, but should not be taken for granted. Accordingly, the physician leader should apply the first component of each PACT Factor to the superstar and provide sound direction, full support, maximum available resources, and sound communication to the superstar.

The next group illustrated in the diagram is the silent majority of steady or organizational advocates. This is the most important group to a physician leader and should be the main focus of organizational communication, as they represent the largest cadre of the team and organization and represent the most dynamic constituency of the healthcare leader, as they are the most able to change and fluctuate in performance based on situation and circumstance. One of the basic maxims of the performance matrix is to manage and lead the steadies in the same way as the superstars—that is, treat the steadies like superstars and over time, they will start performing and exhibiting the same stellar work behavior as the superstars. With that in mind, the strategic leader should incorporate the first (or primary) component of each PACT Factor in their daily communication, and avoid the nefarious effect of the second (or counter) component.

The third and final populace of the performance matrix is the nonplayer, or organizational agitator and instigator. This group, thankfully, is the smallest in terms of size, but unfortunately can take the majority of the physician leader’s communication effort and basic management time. Trying to get the nonplayer, who is self-motivated and self-absorbed to change and become an organizational advocate, can be a thankless and often fruitless endeavor. To minimize that waste of precious time and effort—which can be more productive and efficacious when directed to the superstars and steadies—the physician leader should avoid falling into the traps evident in the second counter component of each PACT Factor. By adhering to the primary component, the strategic physician leader ensures that the superstars and steadies get the support, motivation, and direction through well-calibrated communication that they need, and the nonplayers in turn clearly understand the expectations of the organization not only relative to the what is expected in terms of performance and work behavior, but moreover, understand cogently the how of the organization—that is, the expectation for daily interpersonal conduct and the standards for pursuing excellence in the interest of providing maximum service to the organization’s constituency.

Applying the PACT Factors

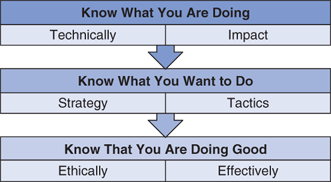

With the performance matrix in mind, the PACT Factors, which set a foundation for the creation and reinforcement of pride, accountability, commitment, and trust, are viable starting points for employing the PACT System. These four major themes can be applied directly in your workplace and underscored in your leadership strategy by examining the dipolar tendencies (first the right tendency in leadership style and strategy, the second listing the converse/negative tendency) for each of the four major PACT elements. The PACT Formula has a basic philosophy (Figure 2–2) that when encouraged by the physician leader can inspire increased performance and confident, progressive individual staff member action.

Moving from the general applications of the PACT Formula apparent in the preceding paragraphs to specific applications under its acronymic aegis, we will now put more PACT Factors into practice, starting with factors and strategies specific to the building of pride in an organization through strategic leadership communication. Pride is best defined for our purposes as a sentiment shared by the overall majority of the organization or team that

-We are here to perform a vital service.

-We believe that we do our jobs individually and collectively as well as anyone in our field.

-We will always do whatever it takes to take good care of our customers.

-We are in the game to win, not just to play.

With the continuing need to change within an organization, based on ever-escalating customer expectations, ever-emergent new technology, and ever-intensifying pace of action, it is easy for the nonplayers to lament current pressures and long for the good old days. As is always the case, they can often enlist the more pliable members of the steady group, and create a sense of doubt about current initiatives and organizational direction. It therefore becomes an intrinsic responsibility of the physician and healthcare leader to constantly educate his/her team about current objectives and future goals, all supplemented with a focus on current demands. Then or the good old days has relatively nothing to do with present-day demands, yet can be a wistful seditious inspiration for the nonplayers and their sympathetic listeners.

To do this, communication in department meetings should include at least one mention of a current event that is directly impacting the organization’s current work. An example of this would be the latest government initiative to provide Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement based on patient satisfaction scores. A physician leader who uses an article from a local paper on this current miasma—and that would be readily available, given its prominence—can then link it to the requisites of a medical office to ensure that every action taken onstage in view of patients is customer friendly and provides the best effort to provide clear communication and compassionate care right from the patient’s entry into the front office.

Closely related to the preceding facet, healthcare leaders must constantly affirm that they are satisfied with the construct of their current team and fully confident in their abilities. This is essential as the nonplayer will reference the past, in which budgets allowed larger staffs and, undoubtedly, more human resources in general that are available now in the era of doing more with less to the point of doing everything with nothing. Citing the wins and notable accomplishments of the current staff, both in a group context and with specific individual, positive recognition is an easy tool that is always available—but often not fully utilized—by physician leaders in their daily communication.

A good technique to ensure attention in organizational communication is to use a word that is not often heard in management parlance. This gets the staff’s attention and can become a nice game among the superstars and steadies, as if the selection is interesting, which can in turn be used as a reference point in ongoing discussion. An example of this is the word, miasma, which generally can be defined as a deliberate, self-perpetuating foggy environment. Nonplayers love to create miasma through rumor, innuendo, and sheer mendacity. Focus on the current objectives of the team is the first step; however, the physician leader must strive to always frame the why of what the team means to achieve every day and at every opportunity. A simple cause-effect semblance is the best method for this.

For example, the practice of walking a new patient to not only the department that will provide primary service, but additionally introducing them to the first person in the continuum of care resonates maximum meaning to the patient entry process. It also eliminates the always-present potential of a new patient becoming confused and losing trust immediately by getting lost in a facility as they try to independently negotiate the miasma of paperwork and the often-vexing physical layout of a medical facility.

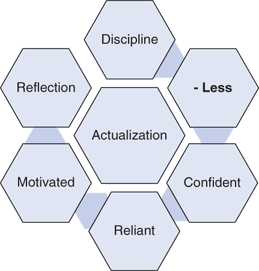

As depicted in Figure 2–3, superstars are selfless in nature and understand that by taking care of the customer/patient, their teammates, and the organization’s objectives, they are in essence taking good care of themselves. The diagram provides an overview of the triad of their success strategy, which makes them natural leaders in conducting the action needed by the organization and directed by their physician leaders. Nonplayers, on the other hand, are self-centered and seek to create cracks in the overall structure—fissure—and particularly in the semblance of their assigned work team.

The physician leader must therefore keep a focus on team objectives and goals and not allow inappropriate and disproportionate time to be spent on discussing individual problems and issues presented—and all too often, conceived in fiction in a fractious manner—by the nonplayer. Two specific strategies are needed herein. First, the physician leader should take the time in group meetings to provide the facts in the face of any prominent rumor in the interest of curbing further conflation by the nonplayer. This should be done crisply and resolutely, and be centered on the true facts, even if that means conveying that a decision has not been made (which is better, for example, than a rumor that a decision has been made that will negatively impact the work group) or simply confirming some bad news as fact. In the latter case, the physician leaders should provide action plans so that their group has an objective to work toward to deal with the bad news; that is, the physician leaders should give their group something to run toward, rather than run from various negative aspects, both real and perceived.

A second strategy is to implement a house rule that all staff members should provide solutions to all problems encountered by team. The staff should be tasked to innovate solutions, with the leader’s guidance, that not only assuages the problem at hand but implements action which is proactive, progressive, pertinent to the situation at hand, and provides a definite, positive payoff for the customer, organization, and team. Naturally, the superstars and steadies of the group will be able to contribute, if not lead, this discussion and maintain a focus on shared direction and action. The nonplayer will be forced to enjoin that discourse positively, or in a very real sense, deal themselves out of the action.

It is unfortunate that politicians have embraced as part of their pedantic polemic the notion that they will be transformative leaders once they attain office, and all too often, become part of a trudging, status quo of inefficacy and mistrust. However, if taken from a more effective venue, a leader who uses a strategy, both in their communication and planning, that is transformative can garner the full support of all of their superstars and the overwhelming majority of their steadies. Transformative leaders are ones who can enact significant change that benefits the organization, customer community, specific work teams, and individual staff members. They can position all of these constituencies in a clearly improved position for the future while leading short-term change catalytically and with maximum outcomes.

As is the case with any sound leadership strategy, the foundation of planning at the team level should start with the staff members who are closest to the action and thus are a boundless front for new ideas that could translate into winning practical and pragmatic strategy.

The physician leaders who ask for the idea of the week at regular meetings and utilize a daily strategy of asking staff members a simple but very efficient question—“What do you think about (a given objective, new plan, or apparent need for action)?”—are those who are certain to have a ready lode of useful information in formulating new plans of action that will be transformative for their organization. Additionally, a natural level of commitment is at hand, as the genesis of the plan came from the staff that must now support the plan with action. Pride is engendered as results abound from the new action, each individual is assigned an accountability for specific action to support the group objective and results are realized from a smarter, better way of doing things—which, in reality, is a very credible application and definition of transformative action.

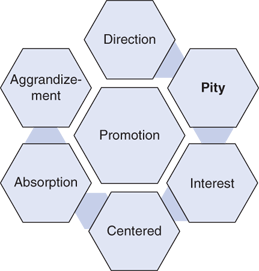

Superstars and steadies want their team to win. As simple as this seems, one only has to consider their devotion to selfless service, which in turn will ultimately provide a sense of satisfaction and achievement on their job. The nonplayer conversely wallows in multitudinous excuses and limitless reasons for why the organization and the team are not prepared, ready nor able to take care of business at a top level. The nonplayers unfortunately can take umbrage in the mass media depictions of the culture of complaint that exists in American society at large and has been aptly captured in several books and apparent on any talk show (Figure 2–4).

Being a victim is almost trendy, and most nonplayers have that role down to an art form. Unfortunately, their whining and inappropriate emotionalism can be a morale buster, and it must be arrested by the strategic healthcare leader forthrightly and resolutely.

Two strategies can accomplish this. First, the healthcare leader should think of teams that they have been part of which have been successful, as well as notable teams from the world of sports and other organizations that can be used as positive exemplars. This can be done most optimally as a group exercise with the team, as it would then be notable, resonant, and jointly owned when ratified and put into action. Three to five aspects of the winning team’s composition should be aligned toward specific group’s charter. An example of this approach would be to use the sports example of the underdog 2012 Super Bowl Champion New York Football Giants as a model, who succeeded through the employs of four criteria:

-Unconditional belief in their abilities rather than what the expert media believed

-Planning their work, and then working their plan

-Adjusting their plan as needed, but all while keeping the main objective in mind

-Knowing that the pressure would be on, but not getting on each other when the pressure was on

Taking a closer look at these factors, it is easy to see how an emergency room team in a community hospital, for example, could easily apply these tenets to their daily work. In doing so, the superstars and steadies would have a clear plan to victory (read: positive outcomes) and the nonplayers would be self-exempting if they decided to complain without merit, or bring up problems without solutions while the rest of the department dedicated itself to building an emergency services department that they could truly be proud of every day at work.

Pride can be built on having a credo—that is, a set of beliefs—that the entire work group can embrace and employ through action. This credo must resonate—echo positively—through the entire work group. The fracturing of communication known as dissonance can be destructive in any work situation, and in some healthcare situations, can actually be dangerous if it leads to miscued action, inaction, or mistakes in treatment. The nonplayer can often create dissonance that can lead to miscommunication deliberately just to get attention in a despicable manner; regardless of the motivation, dissonance over time can lead to a schism within a work group, which ultimately can lead to abject failure.

A basic credo should therefore be forwarded by the physician leader, ideally with easy-to-remember phrases, to have a resonant communication of the basic mission and philosophy of the work group. The use of alliteration, repetition of phrasing, and other communication devices helps to facilitate reference and recall of the credo. The following is an example of a credo that the author helped create for a Veterans Administration Medical Clinic in Appalachia:

-The Veteran Patient has served our nation with high distinction, now we have an opportunity to respond in kind.

-The Veteran Patient drives our clinic, not vice versa.

-The Veteran Patient is a neighbor of ours and from a family like mine, so only the best possible care will do.

-The Veteran Patient can do without a lot of noise, hassle, paper chase, or waiting.

-The Veteran Patient will appreciate all that we can do and will be eternally grateful if we can get it all done.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree